In reference to the Vietnam War and President Nixon’s “Pentagon Papers,” whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, decried: “They hear it, they learn from it, they understand it, and they proceed to ignore it.” Both my personal and professional lives focus on how we can re-interpret “information” in order to embody our interdependencies. How can we learn to decode what we are told is “transparent truth?” How can we educate ourselves and our children to take nothing for granted, to filter perception management and the seemingly self-evident through cultural, historical, and ecological relationships, to unlearn what we think we know and debate differing perspectives?

Four installments, from January to April 2021, will include my personal-political discussion of both the roots and the implications of perceived solutions to climate crisis and environmental racism. We will see how these solutions may unintentionally sustain ecological devastation and global wealth inequities—actually diverting us from establishing long-term, regenerative infrastructures. As we unfold the possibilities of a “permaculture paradigm shift,” we will explore the implications of supply chains that render particular humans superfluous (Hannah Arendt). When radical self-inquiry converges with infrastructural mechanisms and institutional support, we can begin to uproot the foundations of our industrial-waste consumer culture—our internalized fascism (Michel Foucault). We can begin to actualize symbiotic, biophilic solutions as we transition from our petroleum-pharmaceutical-addicted cyber-culture to a biocentric economics.

PART 1

Migration

In search of a home that could support my ardent values for my son’s education, Zazu and I had been living in off-grid intentional communities from California to New York. Even among purportedly radical subcultures, we primarily found bubbles of parents and activists who profess indigenous-wisdom, yet who are unconsciously entrenched in materialist convenience-culture. I was ready to ignite a new life, and then I met Rob…

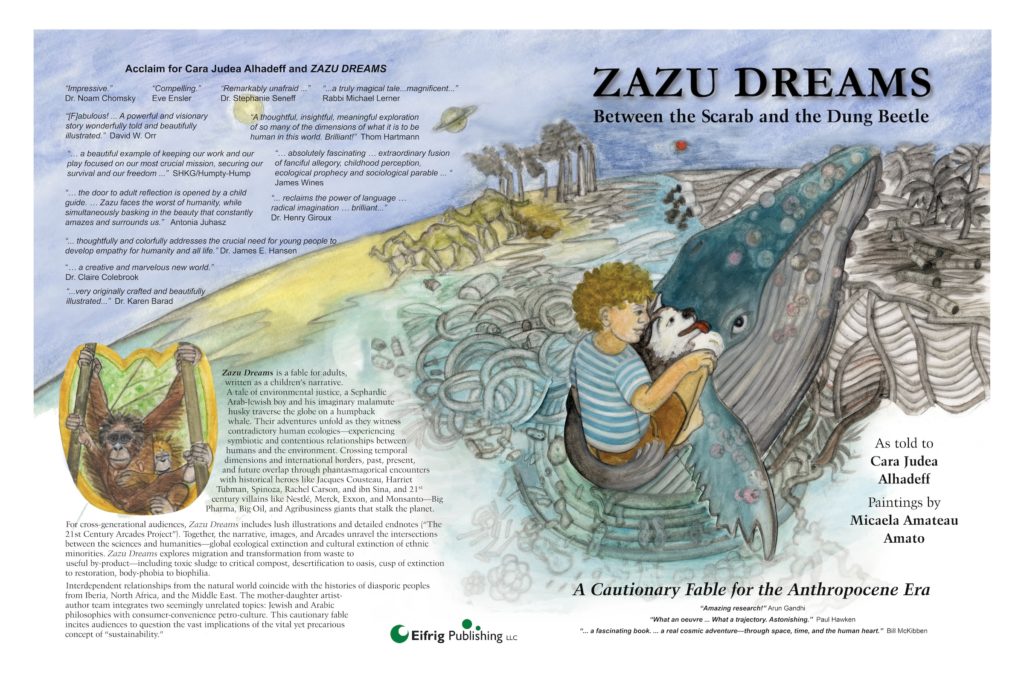

Zazu and I were living at EcoVillage Ithaca. I had learned of Rob’s work as a bat scientist and biodiversity-advocate ecologist and invited him to be one of the speakers on my panel about scientists who use storytelling as a way to catalyze action for social change—the theme of my climate justice book, Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era (Eifrig Publishing, 2017). Among his cuddly bats and our seemingly “too radical” shared ideals about the world we want our children to grow up in, Rob and I recognized home in one another—we fell in love. But, we would have to wait to generate our lives into action. He was deeply rooted in Michigan with Georgia and Madison (Rob’s daughters), his career, and Mac (his rescued golden-doodle, bat-care service dog); and, Zazu and I already had plans to move to Wild Sage cohousing community back in my hometown Boulder, Colorado—a continuation of my research on alternatives to normative, waste-generating economies. It had been 30 years since I lived in Boulder, and now found its pretense of environmental consciousness—challenged by every two-Prius family driving along mini-freeways that had once been walkable roads.

Living this duplicity was compounded by the ache of being in love and so far away. Zazu and I left our beloved Rocky Mountains and moved to our new family in Pontiac, near Detroit.

Urban Blight

In exchange for free rent, we committed to a work-trade rebuilding an historic house up for demolition. This 100-year-old structure, along with many of its neighbors, was officially identified as part of the “blight” epidemic sweeping Detroit. You know the scene: abandoned houses with missing siding and crumbling brick; blown out doors, boarded up windows—neither preventing squatters— people and wildlife (including woodchucks—I never imagined woodchucks roaming the streets of Detroit!); buckling roofs, caved-in porches, missing gutters, peeling paint and insulation; glass shards, tires, beer cans, feces, and other debris littering front yards and driveways; empty shells obscured by overgrown brush and neglect. It turns out that locally there are 50,000 (some estimate twice that) abandoned houses afflicted with blight. If a structure fits the city’s assessment of abandonment and worthlessness, blight is considered the next step before it is slated for demolition.

Zazu and I now straddled two extremes—moving from Boulder to Pontiac—from “Zero Waste” to zero pretense; the outdoor(sy) capital of the world to the car capital of the world. Back in Boulder, almost every weekend Zazu and I would go to events—advertised as “Zero Waste” festivals. These music, art, ethnic-specific, and “eco-friendly” festivals left in their wake shocking quantities of trash. Then in Pontiac, adults and kids would carelessly drop their empty Doritos bag or JOLT can on the sidewalk as they walked along. There was no environmentally-conscious masquerade. I felt relief; they seemed unaware of the greenwashing game, instead simply governed by the lure of convenience-monoculture. We had escaped the hypocrisy of Boulder’s eco-capitalism.

Bureaucracy and the Institutionally Racist and Classist Housing Crisis

We worked hard to complete the house by winter. We maintained our eco-ethics as much as we could as we addressed our landlord’s demands still using conventional building methods—2’x4’s, drywall, plywood, plumbing, wiring, spray insulation, construction adhesive, toxic finishes and paints, plastic electrical outlets—plastic everything. We played by the city’s rules, but still received “Not Approved.” The feeling was mutual. I pulled Zazu out of school after only two weeks; I wasn’t able to navigate the punitive school procedures, candy rewards if the kids didn’t beat each other up, video-instruction, few windows, meager recess, below-poverty government assisted free “food,” and barely any material taught because the kids spent most of their time in line waiting for others to pay attention. Far from the primitive skills, outdoor adventure programs, and forest schools, this was Zazu’s first experience with public education.

I would have thought that the Pontiac school, ironically named after Walt Whitman, would have been an extreme opposite from the progressive one in Boulder—the only“nature” school I could find in all of the Boulder/Denver area. But, both were actually a distorted mirror reflecting the same untenable addictions—everyone driving cars, relying on disposables, dividing our natural world from our everyday lives and the education of children and adults.

And so our search continued.

This article was originally posted on Mother Pelican.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cara Judea Alhadeff, PhD, is a scholar/activist/artist/mother whose work engages feminist embodied theory, and has been the subject of several documentaries for international public television and film. In addition to critically-acclaimed Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era (Eifrig Publishing, 2017), her books include: Viscous Expectations: Justice, Vulnerability, The Ob-scene (Penn State University Press, 2014) and Climate Justice Now: Transforming the Anthropocene into The Ecozoic Era (Routledge, forthcoming). She has published dozens of interdisciplinary essays in eco-literacy, environmental justice, epigenetics, philosophy, performance-studies, art, gender, sexuality, and ethnic studies’ journals/anthologies. Her pedagogical practices, work as program director of Jews of the Earth, parenting, and commitment to solidarity economics and lived social-ecological ethics are intimately bound. Her photographs/performances have been defended by Freedom-of-Speech organizations (Electronic Freedom Foundation, Artsave/People for the AmericanWay, and the ACLU), and are in numerous collections including San Francisco MoMA, Berlin’s Jewish Museum, MoMA Salzburg, Austria, Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, and include collaborations with international choreographers, composers, poets, sculptors, architects, scientists. Cara is a former professor of Performance & Pedagogy at UC Santa Cruz and Critical Philosophy at the Global Center for Advanced Studies. She teaches, performs, parents, and lives a creative-zero-waste life. She is always eager to collaborate with other activists, scholars, and artists from other disciplines. If you are interested please contact Cara via email at [email protected] or via her websites, Cara Judea and Zazu Dreams. See also this article: Social ecology pioneers return to Nederland.

alternative education climate crisis nomad lifestyle Permaculture Sustainability zero waste