All but forgotten, Guadalupe Lara celebrated her seventieth birthday in solitude, in a small apartment on the outskirts of Guadalajara, far from the canyon and the village she fought to save. This plain-spoken country woman became the face of a movement to stop a megadam from destroying her village. The village, Arcediano, lay at the bottom of the Grand Canyon-like Barranca de Huentitán, a national park that marks the northern boundary of Guadalajara. Guadalupe and the citizen movement that accompanied her succeeded in stopping the dam, but her village was razed; more than a decade later, she continues the long fight for compensation for her home and business.

Her struggle was the stuff of Mexican headlines for more than a decade. What few knew about her was that she is a secular laywoman, consecrated to God with vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

This story appears in today’s Earth Beat, an environmental publication of the National Catholic Reporter. The story of the Arcediano Dam has played out again and again in the thousands of cases of megadams still plaguing the Global South. Guadalupe’s victory may have been a hollow one for her, but her struggle reverberates throughout Mexico and beyond. Her story can be read in its entirety in her book, Yo Vi a Mi Pueblo Llorar (I Saw My Village Weep). Guadalupe has stood alongside the stalwarts in the struggle to save Temacapulín from the El Zapotillo Dam, which we write about for Earth Island Journal.

What was it like to grow up in the village of Arcediano?

In my childhood, well, the Santiago River was virgin, it was pure, and full of good fish. And we used to swim, and run through green fields, between milpas, corn, squash; when you live on a ranch that’s how it is.

I am the fifth of six children. We sisters were very close. My mother was a very good, very spiritual person, but my father was a drunk and a womanizer. I was 13 when he abandoned us.

When the dam project began, we were all already getting on in years. My mother stayed with me, and she died here in this subdivision in the year that we came here, which was in 2004.

Ah, when you were just beginning the struggle, right?

Yes, the project had begun and we were fighting it. I asked Don Manuel (Villagómez, one of the movement leaders) to find me a house in Guadalajara where I could rest, because I was under so much pressure. There was the family, the government, the community — they were all against me. So he brought me here, and there were not many houses at that time. He said I found a place for you to rest; I said, OK, but not for more than fifteen days. And look, I have fifteen years here now!

So you grew up with the joy of living in a small town, in the countryside, but with the challenges of a difficult father?

Yes, a father who never wanted to have so many daughters, he wanted only sons, and unfortunately my mother had four daughters and two sons, so the daughters were marginalized. But our childhood was beautiful because we were free, my father would plant, and we would run to harvest the fruit on the banks of the Santiago River that was clean in those days. My dad planted squash, onion, tomato, corn, and we owned my dad’s little ranch.

He had cattle, and he planted on a piece of land that he had, and he had a lot of wild plum. There was a lot of mango in the canyon, too. We didn’t have a mango orchard, but we did have some plum trees. We were really poor.

But maybe you didn’t feel it as much because you lived in the country?

Yes, because the land provides for you, it gives you everything for free. There was a lot of guava, a lot of mango, a lot of guamúchil (a type of tamarind); we harvested it a lot, and we climbed up the canyon whenever we wanted, all the way to the city of Guadalajara.

When did you make the decision that you were going to be a consecrated laywoman?

It was very curious, you know? The idea arose, in the Spirit of God, how that tends to happen. We met some nuns, with my sister who later became a nun, when they went to visit Arcediano. Wow, that got our attention! My sister went with them and came back with Franciscan ideas and she invited me to give some meaning to my life, but I didn’t like the idea of being a religious sister. No, no, I didn’t like it.

What was it that you didn’t like?

For example, I didn’t want to leave my family. On the other hand, there was the way they go around dressed up, it really gave me a bad feeling. And it’s not that God didn’t call me in that way.

You’re referring to the religious habit that they wore?

Yes, their habits. These days the nuns are more modern, they don’t always wear their habits; they wear normal clothes, like lay people. But I never liked the idea of being one of those, so I said no, not me.

So years passed until I learned about the “Hombre Nuevo (New Man)” Institute. I met its founder, and I was invited to a retreat; they had retreats every month and still have, so it was from there that this vocation was born. And I said, good, I won’t have to leave my family — because in the Institute, each person lives with her family. Yesterday I celebrated 19 years of perpetual vows. But I have 30 some years involved with the Institute.

The institute is called “New Man” because we live the spirituality of St. Paul. Its founder is Arturo Martín del Campo Medina; he is a very wise man who worked a lot in social ministry. He was ordained in Rome, and lives in Tonalá (a part of the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area), where we have a house of meeting and prayer. In this Institute it has a branches of priests, another of married couples and another branch of celibates (that is us), and all are to live the charism, the spirituality and the mission. Here in Guadalajara there are about eight, nine or ten institutes of consecrated life like this one.

What was it that won your heart about this institute?

What struck me was their way of being, very simple very humble, their welcoming way with people. God puts in you the vocation. And that’s why I joined them, almost 30 years ago or more.

Tell me about your vows.

It was very nice. There was a Bishop from here in Guadalajara. There was a sister of mine with her daughters, although neither my mother nor my sister Paulina were there. They are very beautiful; there is a lot of joy from all the brothers and sisters, they congratulate you, there is food, there are very beautiful memories, and they are things that are never forgotten, they stay engraved in your mind and in your heart.

Now it was the 50th year of the founder, and each year we renew the vows, but it was truly very lovely.

It is an eternal and definitive “Yes” to God.

Like marriage, in a way, perhaps?

Yes. And I am often called, “Mrs.”, and yes, I am a married lady. I have my husband, who is Christ.

In the struggle, people never knew that I belonged to an institute, never, never, never. And I was about nine years in the struggle. People would tell me that I was very spiritual, that I had a lot of faith. They saw me that I was attached to the church but they never knew that I belonged in those aspects to her.

Why did you never want to share that information?

The moment never occurred. Once a lady from El Salto, she asked me if I was a religious. I told her, No, I belong to an institute of consecrated life, and she told me “Well, you have the face of a little nun.” And I said, maybe she was right. (laughs)

Before those years what were you doing? You never married, right?

We were always catechists, always our whole life. I took care of my sister and my mother, I cooked, I washed clothes, and I took care of my mother, all that time. No, I never married. I had my suitors, I had my admirers, but they didn’t move my heart, so as we were very poor people, I wanted to improve myself, so I started to study primary school. Students from the university came to give us classes, they helped us to study our primary school but we were only able to get about halfway through. So it occurred to me at the Institute to finish my primary school and then secondary school. They gave us a scholarship to be technical educators. It took three years, and when I graduated as an educator and I was already in the Institute and they supported me, they gave me a house to live in in Guadalajara, because imagine, coming up from the canyon every day would have been impossible. So they supported all my studies.

At that point I left because my mother was getting very old and there was no one to take care of her, so I moved back home to Arcediano, and I would climb the ravine in a truck to attend the functions of the Institute.

I had lived there for eight years when the project arrived, so it was about ten years of struggle — then it was canceled, but at that point I didn’t live there anymore. My mother passed away about 10 years ago; she suffered from a disease that made it so that she didn’t understand a lot of things, she just cried a lot when we came to live here in the city. We came to live here in another house nearby. She cried a lot for her children, but she also had Alzheimer’s disease or something like that. She cried a lot, she got depressed and then she didn’t last very long. God took her away, and it was just my sister and me.

And when did you find out about the dam project?

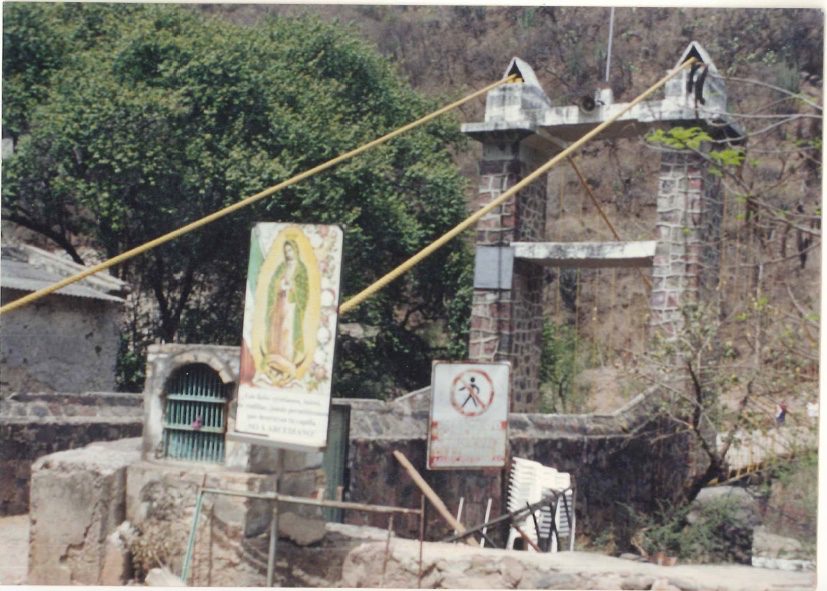

In 2002, there was a gentleman who worked at the Arcediano Bridge. He was the one who charged everyone who crossed over and went to Guadalajara, he charged them to maintain the bridge, so he was very connected with the government of Guadalajara because he worked for them. So he came with letters sent by the government where it was announced that they were going to build a dam, and only a few of us read it. After about a year or less, when we saw that they were more serious, more news began to come, and they said, “You all will be taken away from here.”

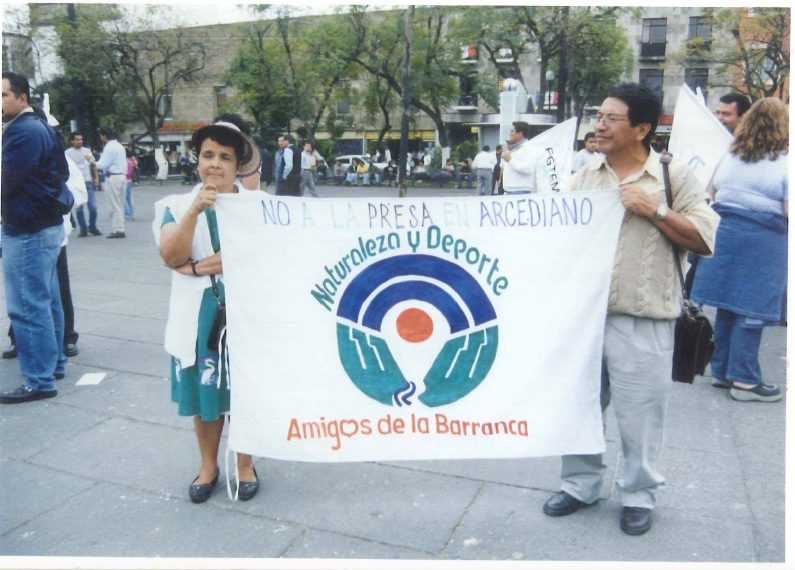

So I decided to be brave and I began to do a survey, with all the neighbors, about who wanted to be moved out of there, and everyone said “no”, and put their signatures on a sheet. And I, being a busybody, I began to get involved in those things. The time came when I wrote a letter, and then Channel 4 arrived, along with other gentlemen to tell us everything they were going to do about the project, and to know if we were going to oppose or be passive, and I with my sheet written, finally I spoke up and asked them if they would let me read it. I read it, and they applauded me. And then they started saying, well, you know what? We’re going to make Lupita the president of an organization. And I said, No, not me, there are more prepared people and more knowledgeable, more cultured, and they told me that I was very spirited, and they were going to leave it to me, and whether I wanted to or not, they put me as president and with a board of directors, together with my nephew.

Don Manuel Villagómez was also there, the whole board of directors was made, and that’s where my cavalry began. Because they gave me a secretary who was useless— I called her Pretty María, because she never wanted to answer, she was afraid, so I was the one who led the fight. I started attending many events, and it was — drive up the ravine, now back down, and now you have a meeting there, now here, and now there. You can imagine. And as the project advanced it got harder, and then the authorities began to take action against me, because I was the opponent, and I was told that I was being manipulated, that I was being used, that they were taking over my freedom so that others could take the credit.

Manipulated by whom?

By them, by people like Don Manuel, who was a legislator at that time, and by all those who opposed the dam. And they said I wasn’t using good judgment, and to this day I am still told that I was manipulated, that they took all my energy, that what they did with me… but I said that’s not true.

They were very difficult years, very hard. I ended up suffering with terrible migraines. It was always: Now we are going here, now to Mexico City, now to Oaxaca, and now here; press conferences … it was very difficult, I don’t even know how I was able to continue. I really don’t know, because once the project was canceled and I was going back down to the village with a doctor for my mother, and the media were there and they asked me:

“Señora, did you see that this and the other dam were canceled?”

And they said: Do you not they realize that they are using you? Don’t you realize that you are manipulated?

-I told them; Do you know what? My judgment is very firm, or else I would have gone right away, at the first handouts of money.

And the media came almost every day to the canyon to my house, to get news, and my family to me put me in front. “You busybody, you gossip, you’re the one that’s all into politics, go ahead! Go out and talk to the media.”

Oh my God. I cried a lot, I prayed a lot, I suffered a lot, and to this day, to this day. I swear, if they asked me again, would you lead another fight? I really don’t know. Because you can’t find support, it’s very hard work; I would go stop at the Toluquilla Red Cross or the Green Cross with a lot of tension, a migraine, and I didn’t have anyone.

There were words of “Stop already, don’t be stupid, do you think you’re going to beat the government? They can kill you, intimidate you,” they told me. Once they were students and they asked me:

– Señora, aren’t you afraid? Look, they can just …

I said: Look, we were born to die, and then what? So what are you worried about, then? And others:

– How much money do you want, ma’am? Don’t you want to leave?

And I said: Look, my fight is not for money, my struggle is for my land, for my habitat, for my dignity, for the corruption of these dirty governments. If it were for money, I would have left. Because there was a time when they offered us a hundred million to leave, and I said: No, not me. I want to fight this thing to the finish, good or bad. I told them that, and so I ended up not being compensated, without my land or my house or my business being paid for. Unbelievable.

And someone said to me: Hey, Lupita, think carefully. Did you get into the fight or did they get you in?

I said, If you ask me that question, it is because you have never loved the land in which you were born, nor your habitat, nor all your surroundings, and then you devalue my land, and you tell me, then why did you fight? Or what if people did tell me to join? I made my own decisions, nobody forced me to do anything.

Once we met with the secretary of Mr. Acuña, who was the governor of Guadalajara at that time, and he asked me, “Señora, don’t you want to negotiate?” I said: I didn’t come for that, sir, I didn’t come to negotiate. And so many people wanted to get me out of the way; graduates, family, my founder himself told me; “Get rid of that, Lupita, how do you think you’re going to beat the government?”

I just kept quiet, but my founder did try to stop me; so did the lawyers, the family, many fought to stop of me.

But it hurt a lot, my people who cried, who suffered. You know, the priest who came to us every month, he gave us an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and autographed her, and said: Never forget to pray. Continue with this devotion. And when I saw my sister-in-law embracing the image with a few tears, I cried and cried, my God … and then she said: “Look, the government already came to me, the dam is a fact, we are not going to win. They have already started counting the houses.”

And I got angry and said: “We have forty houses, what did you tell them? Have you asked the government what we are going to live on?”

And then she said, “You do whatever you’re going to do.” That hurt me so much.

And when the father told them to sign, to not be stupid, one of the people who had been supporting me in the fight said; “No more. Now it’s like the father has put his foot on our neck.” And then the rest of the people from the community opened up to me and told me they were abandoning me, and I was left alone.

And the press conferences for other struggles against dams appeared in Mexico, Oaxaca and many places, and there was the Señora from Arcediano all alone. You know I felt bad, because people would always come to these events with a group of four or six people of the same struggle, and I always appeared alone, and I said, well, what am I going to do? I showed up alone to everything.

Returning to the moment when they started working, when all the work teams arrived, can you tell me about it?

I began to hear the machinery, they began to open large gaps through the hills, and the government began to intimidate people: When are you leaving? Look, this is a fact and if you don’t sign or stay home, you will end up without even a house.” Then all the people said; No, I’ll take the money, I do want a house. But I still said, NO!

Then the people of the government came, the machines came, to cut down trees, to enter the properties; so the people felt they had no other option but to sign. So the first people who left were 15 families, and they didn’t bring a lawyer or anyone, they just went to the government building and waited there.

So then we were just 18 families left in the village, and we went ahead and got a lawyer, but we didn’t realize that the lawyer was part of the government.

So this lawyer, who loved the people of Arcediano by the way, came to me one night and tells me; “Teacher, what the government doesn’t give you, I will give you, but stop this! Watch out, Teacher, I am going to help you, but get out of here; I already talked to the people in the government.”

And I had a headache, and I said, “What?”

I told him, look, I will think about it, and then I’ll tell you.

So for these 15 people who signed their little houses, it was a house paid for, a house torn down. Banamex sent a team to Arcediano to pay people, and they told the people that if they wanted to open an account with them, there they were, and then those people when they paid them, Oh Lord! It seemed that they had been given the coup de grace as they say, all crestfallen, all sad, all avoiding me — nobody wanted to hear from me, and I said, “But I did nothing to you.”

The last 18 of us who stayed, we had a lawyer, but when I learned that he was already very close to those of the government, it didn’t seem fair to me anymore, so my brother and everyone signed, and I was the only one left.

My brother arrives at my house in the morning and tells me: “Come on, let’s go sign the papers.” I said, “No, you go. I’m going to inform the board of our civil association — Pro Defense of Arcediano, they were people from Arcediano and people from Guadalajara —and they said, “Tell them not to sign, tell them not to sign.”

Then I told them, but they did what they would, and then the worst began, as they pressured the people to get them out of there – because it was like, “I already paid you; what are you doing here?” And so they went to everyone, until they took them all out, and nothing was left but my little house and the temple, and they tore down all the houses, on one side and on the other, they knocked them down by machine and then the piles of adobe brick were all that was left.

That was so sad, and I lived here in the city at the time, but I went to the ravine almost every day with a friend. We ate there, we arrived at my house, and in the afternoon we left, and the government had us well checked if we entered or left or whatever we did. This is how my case lasted for a year or two until the house was demolished.

Were you there at the time?

No, we had a compañero from El Salto living there; we paid him, so they came to knock the house down and then they took him, and he talked to me the next day and told me;

“Lupita, we have to go file a claim; your house was knocked down.”

I knew that was going to happen but I didn’t know it was going to hurt so much.

And I said, No, I’m not going, I’m not going; and they told me, “You have to go.”

I don’t know where I got strength, but off we went, and no… yes… the only thing I found was a little Virgin of Talpa statue, thrown on the ground there.

Imagine, there was nothing — no foundation, nothing, everything destroyed. And when we got there to file the claim, there were the lawyers, there were the media, and in front of our house, the government people were waiting to see what we were going to do, as they thought that I would then tell them later; Listen, I’m signing … but no, I didn’t say anything.

They tore down my business, and they also thought that I was going to make a scene, but I still didn’t say anything, and they stood in front of my house to tell me.

I don’t know where I got the strength; well, I tried to explain it in these few pages about my spiritual path.

Once I went to Temaca and a person told me, “Tell me how you did it; how did you manage not to fall, not to succumb, to appear so calm, what did you do? ” I said, Look, I don’t have a magic wand, I just grabbed onto God, and said God’s will be done.

“What a barbarity,” they said; “How did you undertake a fight alone, if we are many here and we don’t get along that well, we are all divided, and you?

I said: Look, the trick is to persevere. I don’t like to leave things halfway; I like to see them through to the end, so I stay until the end. Good or bad.

There were many things that we saw, once I went to Peru, and some people said: Oh, the luchadora (fighting woman) has arrived, let’s see what she has to say! And I said: Look, don’t call me that, because the day I believe it, the fight is over; Don’t tell me that I am a great fighter, a great person, because the day I believe it, that’s the day that it’s all over. (laughs) Curious people, who want you to think well of you, and they call you: “La Luchadora.”

Another person from here interviewed me again and told me that I was a great leader, and he told me, don’t you think you are a leader? And I said No, I am not a leader, I was made famous by the media. I don’t feel like a leader, nor am I one.

I am not a leader, I simply led a fight, for my rights to my land, against corrupt governments; they were so dirty and I unmasked them, exposed them, put out the evidence and told them: You were the ones who were mistaken, not me. We let them know from the beginning.

So we unmasked the government, put it in its place as it was, and that was the best I could do; when many left under the pretense that it was a great project, when all they are giving you is filthy water from El Salto, no, no that’s just foolish. I said to them: If you want the project, take care, you are going to harm yourself with filth, you are going to wash your teeth with filth, because that water is pure filth — so how are they going to give us that?

We accompanied those from El Salto, to Brazil; IMDEC paid our way so we could tell of our struggles, to share them with other brothers who also suffered. I went to Cuernavaca, to Veracruz, to Oaxaca, and so on.

When did you realize that this was going to be your focus, that it would be more than just Arcediano?

I discovered that there were many struggles for water, and that there were many affected, and that it was necessary to give testimony, to support the people in their sorrows, in their anguish. I remember when we went to La Parota, which is in Guerrero, where they were going to build La Parota Dam. The people there were musicians, so they organized three days of presenting their music, and the people danced and danced. They were very happy, very happy, and a stubborn man kept asking me to dance with him.

But no, I didn’t, I had a very big wound in my heart, how was I going to dance and dance, dance and dance with my teary eyes, and my heart so torn? They couldn’t make me dance. That’s why I tell you I don’t know how I didn’t fall into the clutches of those worlds, because as the Father warned me; you escaped, because you were very involved. Because the struggles are not usually made up of women; most are men, and if one gets carried away by those things… but no, my faith was very strong, very solid, and besides I was already an older person, I was no longer a 20-year-old girl to go around getting crazy. No, thank God He took care of me, because I was already consecrated, I just didn’t say anything to anyone.

That is why now that you want to publish it, I say that they know the truth that I was neither a leader, nor a great character, but only a person consecrated to God, and that was where I found strength, courage, because you need so many things for a fight like that, in which sometimes you don’t want to exist. Sometimes when the world is very cloudy, very dark, when you can’t see forwards or backwards, and you say: Oh my God, I would rather no longer exist! There is the possibility of that, what a barbarity — but oh Lord, if I no longer see a future, why exist? Don’t go saying that, they tell me, but those are your dark moments, of pain, of sadness. But then, the consecrated are tempted by the world and by the devil, to succumb and fall into the clutches… But it doesn’t happen just because there is God, and he lifts you up, he protects you, he sets you free, he gives you grace, and that’s how we are able to keep on going.

How was all the chronology of events, when did you come to the city to live?

In 2004, I had a lot of pressure; I had the family against me, the community, the government, and I felt very bad in my head, I felt I was going to end up crazy, that’s why; when a cousin asked me; hey cousin, hasn’t anybody lost their mind? And I said; Well, maybe it’ll be me, because as I stayed until the end. And I said no, well look, thank God no, although I will tell you that many people need psychological attention, many people felt very bad, children already on in years would say, “Mom, let’s go to the ravine, what are we doing here?” They wanted to return to their home. And there are people who have already passed away who also said that: “This is not my house, my house is the canyon, let’s go.” Well, can you imagine? There are no houses left or anything, but they carried their land, their roots in their hearts.

I read an article by Agustín del Castillo, that there were people who got sick, later, that there were even people who died.

Yes, many people died.

How? What happened?

Of sadness. They were not in their habitat, and then look at the amount of money they were given; $350,000MXP ($18,000 USD). They bought very ordinary houses, and what were you going to live on? You were not prepared, you had no studies, you had nothing. Then they took you to the suburbs of Guadalajara. My brother, he opened his little store because he already had a shop and that’s what they do for a living. But they are very high taxes and electric bills. Others went to the countryside near Ixtlahuacán del Rio; everyone was divided. Those who left were more or less buying houses for their children, but imagine with $ 350,000, what kind of house did you buy? Then apart from that, what are you going to live with? Well, it was very difficult. So people were happy while they had a little money, but when it ran out, they saw the reality. A lady recently asked me; When do we go to the ravine? I said, uhhh it’s very difficult, very difficult.

Apart from walking down, is there a way to get there by car?

Yes, on the side of Colimilla, it’s just that there are also guards who don’t let you pass. The ejidatarios of Arcediano, they come in their pickup trucks and go to pick mangoes, or they go to fish, they are going to see their cattle — they do have a pass card. But if I show up in a car like that, they won’t let me.

When was the last time you were there?

Well, many years ago I went, we went to an event in Temaca, and I presented; crying all my life story, then they put a video of me, “Oh my God, I caught myself crying again,” then a journalist from the Mexican newspaper, El Informador I think, came up with an interview, then said: I want to go to know your place of origin, let’s go! So we climbed down by another route that’s very steep, and when we reached the bottom, the guards told us; There’s no passage through here. Then we went back to take the road — that was years ago, and he said that of all the cases he had seen, mine was the one he admired the most, and I think it’s because I was alone.

Another journalist told me: It’s because Lupita faced the big governors like the Acuña government, the governor was a cruel man, very cruel, very bloodthirsty, very bad. And look, Lupita, How did you face him? But I never really ran into his face, no, always his secretary, or his minions, as I said (laughter).

But, they did admire that. And they say: How did she face that one alone?

And it’s over now, but it leaves many after-effects, in your mind, in your heart; it’s like, you hear a bird singing, and you say; that bird was from the ravine. And you see so many beautiful things when summer comes, and you remember your canyon, all carpeted in green, all beautiful — and then it gets you in the heart like that.

The other day a boy told me; Hey Lupita, I’m going to start helping you sell books, bring me to the gateway of the ravine, he says, Aren’t you going to look down? I said — No, my heart hurts, I’m not going. But the sunrises and sunsets are precious.

It is difficult because I also no longer have the same physical condition to undertake a descent and an ascent. Once we went like five years ago, to pick mangoes, to the Green River, and to go fishing. A boy passed us by boat and then I told him; You know what, I am going to go to my land because there it is nearby, then he said: Take a machete. I said, A machete? For what?

– Take it, so they won’t scare you. But I didn’t want to go into my land because it’s very lonely, or at least you think it’s lonely, but God knows what kind of people might be back in there.

I told the friend who went with me; We’d better go. So we went back over the bridge, not the one they tore down but another one that they made there of stone, and we were arriving at the part where there were guards and one said, Where did you go that we didn’t see you? And I tell them; Well, we passed you by boat on the Green River, and he said, what about that machete you are bringing there? And I told him; I didn’t even realize that I had it; they lent it to me, I’m going to return it.

I didn’t hide the machete or anything. (laughter) There are so many adventures that one lived.

What is the town of Arcediano like now?

Now it is pure rubble and a lot of weeds, but I who was born there, I could say here I was living, another one here, and another one here. I realize all that, but for those who didn’t live there, there is nothing there.

When did you hear about the fight to save Temacapulín?

We started here with the one of Arcediano and then the one of San Nicolás happened, then they managed to cancel the one at San Nicolás, the same government of Acuña, but he then opens the possibility of the one affecting Temaca, El Zapotillo. So once we went there, Don Manuel and I, the first time, and there we made them see what the project would bring, that it was going to flood them, what was going to happen to them; and I remember reading to them what I wrote there, what we will never forget. But there were just two or three people, and they were not very interested.

But we kept going, and we were in contact with those against the dam, because I know the majority, for example I know María Alcaraz who is now the municipal council member; I know Don Poncho, they are many who I know, very good people. We always try to share the struggle, so that it doesn’t happen to them. There were events and Maria invited us, we were always with them. I wrote them two letters, which are there in the book.

Because I met Father Gabriel when he was very attached to the church, before he left the priesthood — well, basically he was thrown out. Look, it hurt me a lot, because he was a born leader, a big leader, a leader that everyone trusted.

And once I went with a sister to Temaca, and she said; Father give me your blessing.

“No, sister, I am no longer a priest,” he said.

I said, “Look, no one is going to take the priesthood away, not even the devil can take it away, because you were consecrated an eternal priest to God… So you are a priest until the end of your life.”

What would you say are the lessons of the struggle in Arcediano?

I have always said that the world is a school, in which you learn the positive and the negative. In terms of the Arcediano project, many people thought we urgently needed that water, but three quarters of the city knew that it didn’t work, that the fight that was undertaken was not very useful, but it left a mark on all, especially the natives of Arcediano; it left a very large mark on them. In the government, perhaps some hearts ached when it was canceled, because I heard that they said, but why was it canceled? If people are easy, they didn’t oppose it; on the contrary, it all went very well. But as they say, it’s a long way from the words to the deeds. Now they have to remember that stubborn lady of Arcediano: “What happened to her? Where is she? Have you been paid or how is that?

Many are amazed when I tell them that I have not been compensated, how is that possible? Here the lawyers played an ugly role, they abandoned me, those who understood the fight have gone to lawyer after lawyer, and even now, nothing. But the projects that arrive cause a lot of damage, to the people and more to those who fight them.

So if you are looking for a lesson for others, well, that’s great; if they want to say, I’ll go to her, I’ll ask her how she did it, what she did, what she didn’t do, where she went or how the people supported her.

Well here we are, as they say, to let people know that these struggles are not easy, and that it’s not just anyone who is willing to undertake them, but that there are those that feel a spiritual call, those to whom God calls, and there he puts you and well, although we fight at times with that God, because we disagree with Him, but you always come back to the same place in the end.

Many said, “Silly woman, she could have walked away with a lot of money,” because yes, they gave you a lot; but I came to say that my struggle was not for money, but for my habitat, for my rights, for the corruption of governments. So yes, we are like an open book in which you can learn many things, it’s true.

Do you have regrets?

You know, yes, I do. Because of my sister — I remember a cousin, he went and told me, and he was right; that I never asked my family for their opinion, but I dragged them with me to my fight, and I stayed that way, oh my God … “Ask your brother and sisters for opinions to see what they say to you.”

Then I remember once, my sister, the one that came crying, and she tells me; Guadalupe, let’s go; look, they already knocked down the house that was left, we’re going to be left alone, what are we going to do? Come on, let’s go.”

And I very bravely tell her; Look, take my signature, take everything and go, and cancel the lawsuits, and take everything. You do it, because I am not going. I give you the freedom to do it. You go to the government, and tell them I bring the signature of my sister who does not want to, but we want to be paid.

And she said to me, “That’s the way you are, so stupid.” And that hurt a lot, and it still hurts.

It hurts because of the way I dragged them to my fight, right? It’s ugly, and that hurts (tears flow) — but now to overcome it.

And where is your sister now?

She lives with my brother in Huentitán El Alto. You know, my brother stayed there and he bought a house, but his wife died four years ago, and they were left with three children, two grown men and one woman, but my sister for love went to care for their home, so she sweeps for them, mops for them, irons, helps them sell sandwiches, and comes here to visit me every week on Saturdays, and I go to visit them once a week, but my brother, he never asks me; What happened to your case? He just once told me; Well, hey, I went to see some friends, and they told me, hey, are you that luchadora’s brother? That’s what they called me, the luchadora. And he said yes, my sister is Señora Guadalupe, and they said, hey, how did it go? Like saying how much money; and he said; Well, such a stupid thing, she lost everything, ended up with nothing.

And I sat there for awhile… and how ugly that feels, doesn’t it?

There is a song that says: “Everything I had was lost,” or “What I was fighting for was lost.”

Padre Gabriel once told a sister of the Institute;

-Hey, isn’t Lupita Lara the woman who fought the dam? (He didn’t know me very well). And the sister told him:

– Yes she is.

– Well, what is she doing with you?

– Well, she’s a member of the institute,

– (Expresses surprise) – What?

– Yes, she belongs to the Institute of the New Man.

– That’s amazing, what a great person!

– Yes, but she lost everything, the sister told him.

– No, she won a great dignity before the world and before God.

And I say; But you don’t live on dignity; who’s going to pay you for that?

– But that’s what he told me, I had gained great dignity.

– Yes, but you don’t eat that, (laughs)

-Ay, no – there are so many funny stories, the things that happen.

And talking about this, what do you live on?

I live from what (President) López Obrador gives me, to those of 60 years and over; he gives them money, about four years ago we got into that, they gave $1,170 pesos every two months, so we could pay for the telephone, the water, the gas, the electricity, that’s about it, especially now as things are about double what they used to be, but with my sister’s and mine, we live thanks to that.

But before López Obrador?

I worked; you see, I crocheted a lot. Although now with my headache I no longer crochet. And I made bathroom sets, I made scarves, I did many things, I painted — but now I don’t. I’ve had this problem with my migraines for so many years – but look there, I have one of my scarves, I’ll give you one, so you remember me.

It’s beautiful — but I’ll never forget you.

I say look, I prefer to sell my bathroom sets, my scarves and all that, but I realized that I couldn’t anymore. I said no, it was silly to say that was true, because you can’t live from that.

Did you ever wonder, if Jesus were here, what he would have done in your place? What would Jesus do in the face of such a mega project?

I imagine that he would have fought it, too. He would have fought to stop it, but with his struggle of love, with his struggle of testimonies —not fighting revenge, not killing anyone, but a fight of the heart, right? That’s what I think, because he is God, and he would not have gone face-to-face with the government people – but maybe he would have, because there are gospels where he narrates and calls the politicians “a race of vipers” he says to the governments, “bleached sepulchres” and “foxes,” he calls them — so maybe, yes, maybe he was capable of that (laughs).

Only God knows! Only God, right?

- A Year of Listening, Resistance, and Hope: Reflections from The Esperanza Project - December 30, 2025

- Arts to Breathe: A Continental Act of Dignity - November 28, 2025

- “It’s not grass, it’s a milpa”: Defending Life on Avenida Federalismo - October 8, 2025

Arcediano Dam Guadalajara Guadalupe Lara Megadams megaprojects

Heartbreaking story. What a remarkable woman! Its true government officials are mostly vipers. Thank you, Dear Tracy for this window to her world!

It is very important that these stories are published, disseminated and be in the public domain, only in this way can citizens know not only about the corruption that exists in government offices but also about the struggle, surrender and courage that citizens such as Lupita manage to make a difference. Fight and effort that we all should not ignore.