This edited interview is a part of the EcoSapien Speaker Series segment featuring a few of the visionaries behind the Vision Council, Guardians of the Earth, as we prepare for a new Vision Council event, Embrace of the Amate, Dec. 4-11 in Tepoztlan, Morelos. The EcoSapien Speaker Series is a project of Earth Sky Woman Tami Brunk and The Esperanza Project’s Tracy Barnett. This interview was conducted by Tami as a part of the Restoring Sacred Culture in the Americas Convergence.

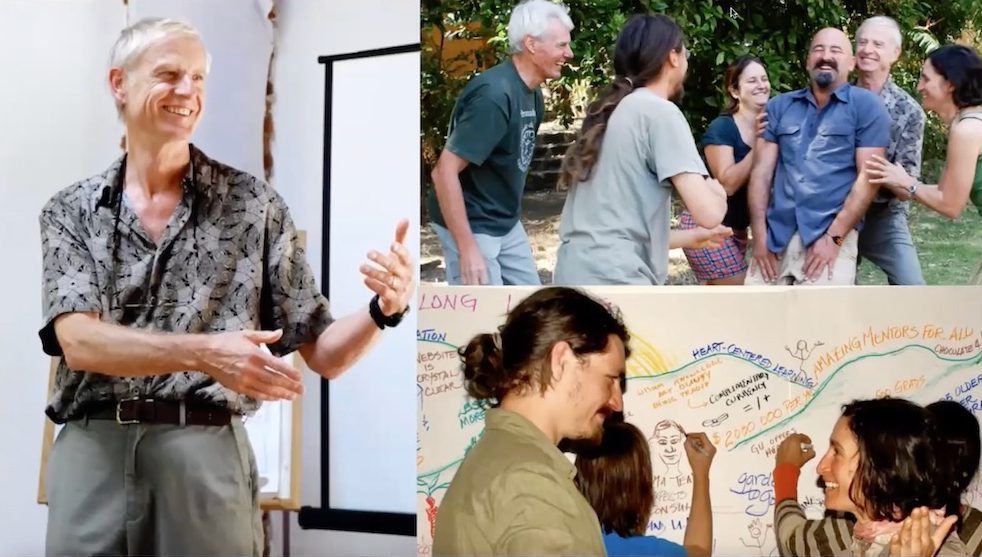

Liora Adler is a visionary social actionist, educator, facilitator, mentor, event organizer and dancer. Raised during the ’60s social movements in the US, she came to understand that protest alone was inadequate for making substantive societal changes. Consequently, throughout the ’70s and ’80s she explored supportive community building that provided both for physical needs and the basic human need for belonging.

In 1982, together with Alberto Ruz Buenfil and others, Liora co-founded a thriving ecovillage, Huehuecoyotl, in central Mexico, and in 1996, a mobile ecovillage and training center, the Rainbow Peace Caravan that for 13 years, shared knowledge of ecological systems and regenerative living while activating ecosocial movements throughout Latin America.

Liora has been a global leader in the ecovillage movement, where she served on the Board of Directors of the Global Ecovillage Network and as a representative to the United Nations. She has spent most of her adult life in Mexico and other parts of Latin America where she also helped form a village women’s sewing cooperative and a men’s campesino collaborative.

She is a fluent Spanish speaker and has significant cultural and socioeconomic sensitivities. She has organized courses, workshops, events and artistic activities for hundreds of people, including farmers, indigenous peoples, and permaculture practitioners on five continents. She was the lead organizer for the 2003 bioregional gathering of 800 people in Peru: The Call of the Condor.

As co-founder and co-president of Gaia University together with her husband Andrew Langford, Liora has been intimately involved with its design and development. She also oversees operations and mentors students and staff. Her feisty, outgoing nature, her capacity to negotiate for practical action in challenging situations and her resonance with people living both very simple and highly complex lives are key to the success of the project.

For the last several years she and Andrew have returned to their home in Mexico and put their attention to the pioneering alternative accreditation system they have been developing: ICAAFS- the International Coalition for the Accreditation of Ancient Future Skills, as well as a Regenerative Agriculture project in collaboration with the UNDP and Department of Organics of the Ministry of Agriculture in Syria, in which they have been training 100+ field and extension agents in permaculture, biointensive and syntropic techniques which they pass along to the local campesinos.

And if that were not enough, she and Andrew have now become the Knowledge Exchange Coordinators of the Ecosystem Restoration Camps Foundation, which is supporting Earth restoration in over 50 camps around the world.

With so much on her plate, these days Liora dances to the tune of “older and bolder.”

Tami: Welcome, everyone who is here now, and everyone who listens later. What a beautiful gathering this is. I’m so excited to be here with the one and only force of nature, Liora Adler herself. To give a little bit of background, we are on the final day of the EcoSapien Speaker Series and the Restoring Sacred Culture Convergence. I have been looking forward to this conversation with Liora the whole time. Liora, I’m not going to read your whole bio because I really want to make the best use of our time. But Liora is the co-founder of Gaia University. We also have the other co-founder here in the room, Andrew Langford, which is exciting. She has been a force in the world of ecovillages, of these new emergent regenerative eco-social systems that we’re creating, this parallel reality to the one that most people are living in. And there’s so much more.

Liora: Thank you so much, Tami, for setting this whole thing up. It’s really been a delight. I haven’t been able to be part of most of it, but I did get to watch some of the videos of it – and talk about force of nature. What you have endeavored here and accomplished has been just really awesome. And I really congratulate you for the vision — but not just the vision, but for bringing it into reality. Because it’s one thing to have a vision, but to actually do all of those little steps, all of those little practical things that are needed to make it happen — wow, that’s just really awesome.

Tami: Thank you. Thank you for saying that. That means a lot to me, from you. And it makes me think, this is one of those strange things — I don’t know how long it’s been since we’ve talked, but I always feel you. I always see you out there. I consider you one of my deepest elders and mentors and friends and soul kindreds.

The first time we met, I’ll never forget, because it was at the beginning of the Vision Council event “The Call of the Condor” in Peru, this massive, incredible event that would draw 800 people from 35 countries. And when I’d arrived, I was tired, I was confused. My Spanish was rusty. I arrived in this place, the staging ground for this gathering, probably a week before, and the people who were supposed to make this event happen were stranded.

This caravan, we’re not going to go into too much detail, but this caravan of all the helpers, they were stranded in Ecuador, I think?

Liora: Well, they had been in Ecuador and they were waiting, I think it was Odin who was going to show up and it was taking a longer time than they expected. And so when they finally got on the road in Peru, they had a huge accident. And one of the buses in which they were traveling got completely demolished. I was up in Cusco waiting for them to show up — because the idea was, they were going to set up the camp. I had spent ten months figuring out all of the logistics and where things were going to happen and who was going to do what and the finances of it and all of that. But I thought, okay, when the caravan comes, they know how to set up camp. They’re really good at that. We’ve done that so many times everywhere. And what actually happened was that the stranded people from the bus showed up in Cusco and they were completely traumatized because they’d been in this terrible accident. The bus that they were traveling in was demolished.

No one was actually seriously hurt, which was really great, but they were traumatized. So it was an added layer, shall we say, of work that needed to be done. But eventually it all came together and it was a month-long event. It was really quite awesome.

Tami: Wow, amazing. Thank you for bringing back some of those memories. And when I got there, probably a week before, you looped me right in so I could help. I don’t even remember, I felt pretty bewildered. But you were just very steady in the middle of this chaos from all these years of this work that was very much in the moment, tending to what was in the moment. At Gaia University, they practice action learning, where you get in there, you charge in and you do something and then you reflect and you learn by putting yourself in real time, making things happen. And the wisdom you carried from that lived experience was evident. Alberto is going to share more of all of these stories tomorrow as well. But I always remember you and the way you took me right in. And you engaged me in the process, the way you were able to be at the center of the storm and make things happen. And those are qualities, those are abilities we need now. Liora has some slides she’s going to share, and a program that she’s going to introduce. And then I’ll ask questions and we’ll have Q&A.

Liora: Thank you, Tami. Well, it’s been a pleasure to do this. It’s been a little challenging, too, because I’m not so good in the technical part. But, you know, I turned 75 in December last year. And that was a really important moment in my life because I thought, well, you know, maybe I have another 25 years left on this planet, and noticing what is going on it’s hard to ignore, and I wouldn’t really want to ignore it. So I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how can I, with the experience that I have, with the values I have, with the vision that I have, how can I best make use of whatever time I have left in my life? I have always tried to be an inspiration for other people, and as you say, to pull people into the action learning part of it, and what can I do in order to be of service to the planet I love, to Mama Gaia.

And one thing that came up for me was the 1972 Limits to Growth Report. I don’t know how many of you have had a look at that, but a group came together, the Club of Rome, and 50 years ago, they put out a report which basically said “come on, people, let’s be realistic. There is a limit to growth. Growth is not a continuum forever.” And so this report that was put out in 1972, I think it still has a huge amount of relevance, or maybe even increasing relevance right now, when we have been involved in this myth of progress. If I look at the world and the attitudes people have, people seem to have this idea that progress has to do with increasing economics. It has to do with earning more money. It has to do with bigger, and bigger is better. And it’s a myth. And it’s the myth that I think has been one of the key factors in leading to the kind of destructive energies that we are experiencing on the planet right now. I think we know about them: climate change, food and water insecurities, human trauma — and human trauma then leads to irrational decision making.

And that “myth of progress” is actually, I think, the main driver of the wholesale destruction of all of our planetary support systems. So then I thought, what do we do now? So where do we go? If we think that the myth of progress is one of the key drivers, what do we do? And my dear friend Alberto passed me and Andrew, a science fiction book called Star’s Reach by John Michael Greer, which is worthwhile reading. I got interested in him and his whole vision of what he calls deindustrialization and read a different book of his as well, which is called Retrotopia. And Retrotopia is all about how can we go back to some of the low-tech and highly effective solutions that we lived, many of us, those of us who are maybe in our seventies or even people who are in their sixties knew about this stuff. I grew up in the sixties, as you can imagine. So that was a very unusual and very special, exciting time. But how can we take those kind of lower-tech solutions and make use of them now?

Now we have large scale solutions that are excellent. My dear friend Albert Bates has been promoting biochar, a really significant solution, a potential solution on a wide-scale level to all of these problems that I’ve mentioned, not just for climate change, but biochar can be used for many, many things, paving roads and building buildings and making it into fertilizer and so on. So if you haven’t read Albert’s books, do it because the biochar solution and all his books — “Burn” is the latest one — all of these give you a really good vision of how it could be if these things were adapted. And Andrew and I are working with the ecosystem restoration camps and communities, and I see we have a couple of camp managers on the call, Teryl Chapel and Leo Lauchere, and all of these are excellent solutions. If adopted on a large scale. They need funding, they need support, they need political will, they need all kinds of supports to get them out of this marginalized place that we have been in. We who are enamored of all of these alternative solutions that we have been creating and promoting since the sixties. And while it’s happened before that, I don’t want to take away any of the credit for the people, even in the twenties and thirties and forties and and centuries before. But we who have lived through this since the sixties, we’ve been doing our best to promote things like ecovillages and eco cities and bioregionalism.

We have all these solutions we’ve been promoting, doing our best to make them happen, to bring them out into the larger world, to get support, to get funding. The ecosystem restoration camps now have more than 54 camps all over the world. That’s fantastic. Is it enough? No. So that’s the issue that I came up against when I began to think, well, how do I want to spend the rest of my life? How can I make or continue to make a difference? I think I’ve made a little bit of a difference in my life, in some ways, at least some people tell me that that’s the case with them in their personal lives. But how can I continue to promote the kinds of activities that will potentially inspire people in their personal lives to lower their consumption? Lower their use of fossil fuels, lower the activities that create a conflict. Colonialism. Oppression. I’ve noticed there’s a lot of personal conflict that is happening even in our ecovillages. I get word from other ecovillages that people are not able to find this kind of harmonious vision and action that we imagined when we started these projects. So all of this is a way of saying deindustrializing. This is a solution that we need to put into effect.

Let’s do the biochar. Absolutely. Let’s do bioregionalism, let’s do de-industrialization. Let’s do all of those larger scale solutions that we know need to be done, find the funding and political will. It’s not just one thing. Let’s do the both/and, let go of the myth of progress, set up our ecovillages and eco cities and regional caravan projects. I’ve been on a lot of caravans, so it was very hard for me to not put in the caravans. You know, they do use fossil fuel. So I said regional. Let’s imagine a small farm future. We need to grow food. When I began to think about what are the essentials of life — Well, we know what they are. It’s not some kind of brilliant thing to imagine what the essentials of life might be. They’re food, and we need water. And we need human intelligence and consciousness and decision making. So let’s set up our ecosystem restoration camps and communities. Let’s set up our small farm future.

What I noticed, I live in a rural area here in Mexico. A lot of farmers are not farming anymore. They’re selling their land to people who want to build houses. And then what do they do? They buy taxis. Is this going to give us an intelligent, rational, graceful, deindustrialized future? Absolutely not. So how can we, as individuals, in our own lives, promote these kinds of projects, this kind of change? And how can we help support other people to do that? So what do we need? We need sane systems for governance, for economies, for food production, water retention, land distribution and dealing with human conflicts. So it occurred to me that those of us like myself who have since the sixties or whenever experienced some of these simple living practices — because when you’re on a caravan, you’re dealing with a lot of resilience. And that word kept popping up for me. We need resilience. We need to know how to deal with situations as they arise. And we need to learn how to deal with less. We need to imagine that potentially less is actually more.

And that’s when I remembered the Bolivian vision of buen vivir and my friend Bea Briggs said to me, “people might not know what buen vivir is.” What’s buen vivir? Buen vivir is good and graceful and intelligent living, which doesn’t necessarily mean living with more. It doesn’t necessarily even mean living with money. There are indigenous tribes who live even without any hard currency. And are they unhappy? I don’t think so. It doesn’t seem like that to me.

80% of the Earth’s biodiversity is being protected by indigenous people who comprise 5% of the population. So let’s learn from our elders. They call me an elder, but actually I’m just a gal who grew up in New York and became a hippie. So let’s learn from our real elders, from our indigenous elders who really know how to live on the land and live in this way.

So anyway, that’s the message I wanted to get across to all you good people who came. I am very grateful that you decided to spend the time and come on the call. Many names and faces I see who I know. And thanks to all the people who I don’t know and new friends. So thank you very much. I prepared a little slideshow with some music that has always been very inspirational for me, and the message is for any of you who are thinking, What is it I should be doing right now in my life?

So I’ve put together this little slide show, it’s 11 minutes and 51 seconds,and it’s got some inspirational music and it’s all about how to get to buen vivir, really good living with less. And the last song is one of my favorite songs. And if you don’t speak Spanish, it’s called cambia, which means change. And I think that’s one of our greatest challenges right now, is how do we deal with the need for change? Change is not so easy. We get into habits.

And it is one of our great challenges to get out of our old habits and to, well, maybe find some new habits, but to get into a place where we can be highly conscious and aware and in the now and find the way to be as resilient and adaptable — there’s a whole movement called Deep Adaptation right now, which I follow, which is all about adapting to the changes that are coming, because I am completely convinced that changes, even greater changes than we have been living right now are coming our way, and it is up to us to become as deeply adaptable as we possibly can.

Tami: Wow. That was amazing. You got me all teary-eyed in the very beginning. What was happening in my mind and in my heart when you were first sharing was in the beginning of it was just this felt sense of how so much of what’s precious is exactly what’s in the line of extermination right now. And that’s indigenous communities, that’s these ecosystems, it’s even in elements of our own psyche and consciousness as human beings. I mean that on the level that our imagination or our capacity to dream, our capacity to create beauty and art from where I’m sitting in the US at this moment, where astrologically we’re in the Pluto return, that’s a big theme right now, which is that we in the US are in this place of massive need for massive shift and change. And it feels to me like what’s powerful is that many of us have a deep longing that’s waking up. But there are also many, many forces that would help us to distract ourselves or go unconscious still. So I’m wondering. I want to just start with, What do you think about what’s happening in the US right now specifically? What do you see that’s hopeful? How do you see our current moment in the US specifically? I think you have a unique perspective.

Liora: Well, I think it’s difficult because I’m not actually living in the US. And so what I get from friends who live in the US is that things are not easy, but yet there is a certain amount of progress. I don’t pay that much attention to what the news media send out because I think a lot of it really is very suspect. It’s very promotional. But in terms of, say, ecosystem restoration camps, there are more ecosystem system restoration camps being formed. The ones that are in the States have been growing as well as the number and size of ecovillages. And I hear from Albert, who’s at the Farm right now in Tennessee, that there are a lot of amazing things that are going on there. One of the things that really inspired me from the Farm was that a group of people who were from the original farm members, we’re talking about the early seventies when the Steven Gaskin caravan, Monday night class, all of those things were going on.

Some of you might have heard of them, and they started getting together and talking about the original visions and how they might be bringing some of those visions back into effect in the present moment. There’s something that happens when people get older, and it’s not just on a physical level. I think it’s also on an emotional and an intellectual level as people tend to talk about hardening of the arteries. Well, there’s also sometimes a hardening of the visions into a vision that maybe is more close to the way in which people grew up. I’ve noticed that people if they grew up middle class, they become more middle class.

Andrew was telling me this morning about someone that came through, I think a Colombian man who came through Huehuecoyotl, and I think it was this man who was talking about how they’re making a whole large community in Colombia. And in the beginning they said, well, private property is a really challenging part. And he said that they recognized that when they set up their community, and people said, well, we’ll start out with private property, but then later after we get things going and so on, then we’ll turn everything communal. And when it came to that time, the majority of the people didn’t want to do that.

Tami: Imagine that. Right. (Laughter) Yeah, that makes sense.

Liora: And I see that here in Mexico, like there’s a whole tradition of ejido and communal land and so on. And as people continue this myth of progress and think that by earning more money and so on, they do get more comfortable. I understand that there’s a certain level of comfort that we as human beings might have, but as that comes about, there is maybe less community and more individualism.

Tami: And maybe that’s part of what I see happening in the States. Yeah. Thank you for sharing that. Thank you for those reflections. And we can talk more about where you’re at. And even since we saw each other or since you’ve started Gaia University, because that was really the last time we saw each other — I’m just I’m really curious about how some of your perceptions have transformed or changed since you began Gaia University? How has your thinking been transforming around community? And you’re starting to talk about that with what you’re saying right now. Or how has Gaia University University and the work you’ve done with that changed you, or changed your perception — Evolved it? It’s kind of a bigger question, but…

Liora: For one thing, it put me in front of a computer a lot.

Tami: I know. Right? (laughter) And I feel that, too. And I think I’ve felt this with you from the beginning. I get it. The one who’s doing the administrative work, because there’s a lot of administrative involved with big structures like Gaia University, probably way more administrative work when you’re trying to build a system that runs counter to the larger system — so even at The Call of the Condor, I recall you were the one dealing with finances. You were the one dealing with these institutions, the things that none of the Rainbow Caravan — you know, most of these beautiful, artistic, colorful people did not want to do that work. And I’ve told other people this when they’re really drawn to this work, it’s like if you want to be an activist and create beauty, do administrative work, write grants, you know, do that stuff — because nobody wants to do it, right? It puts you in front of the computer more. Yeah. So I put you in front of the computer more. How have you navigated that as somebody who wants to effect social change, but it actually goes counter in some ways to what you want to create and see in the world. How do you navigate that?

Liora: Well, one thing is that I’ve actually always been fairly good at that kind of organization, so it comes fairly easily to me. I grew up in New York City, and I grew up in a middle class environment. I was good in school. I entered the sixties. I went through school very fast. So I graduated high school at 16. I graduated college at 19. When I graduated high school, it was only 1963. I graduated college by 1966, and by 1968, I was done with graduate school. So the ability to navigate those kinds of systems were already in place in my life. What I didn’t have was computer knowledge and all of that, and I had a whole bent, which one of the reasons I put together this slide show for you all was that I wanted to go back to my photos and some photos from other people as well, and kind of relive and give you an experience of some of the more artistic side of myself, the visually artistic side. I’ve done many things in my life. I did stained glass, I did batik. I helped the women in Amatlan nearby make a sewing cooperative. I learned how to design clothes and so on. So I’ve had that kind of experience as well. So how did I manage all of that sort of administrative stuff? By balancing it out with more of a creative side of myself. Sometimes it feels a little out of balance, but I have continued with a more creative side of myself. I was an astrologer for a while (laughter) — not like you, Tami, but I do a little of that as well.

Tami: That’s amazing. And of course, when I first met you I saw that interweaving. You’d brought Jose Arguelles, convener of the Harmonic Convergence, to the Call of the Condor. He had a strong spiritual influence on many at the event. He was there alongside the indigenous elders–a very interesting mixing. Let’s go back to what you’re saying about balance–you have many gifts you carry and some core gifts a lot of people don’t have. I think you’ve done a wonderful job of bringing your strengths from the North to the movements of the South; embracing that while finding balance inside yourself. I know you and Andrew and Gaia University have also woven re-evaluation/co-counseling processes into the framework of the program.

Gaia University was ahead of its time integrating healing modalities into the environmental field — something we are finally seeing emerge into the movements as a whole. I was just interviewing someone who brings the somatic approach into climate talks. Clearly you were trailblazers in your design of Gaia University as a holistic model. You have to tend to the spirit, you have to tend to the trauma, you have to tend to all that on the individual level at the same time you’re trying to address the larger global systems. I’m so appreciating Gaia University’s work in these areas.

Liora: Speaking of Gaia University, it seemed to us that our movements should have our own University. Now, that’s pretty challenging because there’s so much stagnancy in the global university system. And we found that out as we were trying to kind of find that balance with Gaia University of being something that was credible and legitimate. And in the beginning, we did find Revans University, and they were our accreditors for a while. They had their own university in Vanuatu, kind of strange place. But still there was a certain level of credibility in that respect.

And now what we decided was that we need to develop our own accreditation system, because the accreditation systems of the conventional universities are so not applicable to the kind of work that we are doing on a planetary basis. I don’t know if you noticed, there was a logo of iCAAFS at the very end of the slide show. And iCAAFS is an accreditation system that we’re developing–the international coalition for the accreditation of ancient future skills. So our thinking is that we are the movements that are promoting ancient and future skills because those ancient skills are the skills we need for the future. So Andrew this morning was saying to me–we should have a retrotopia badge for people.

We had one of my son Ari’s colleagues come over this morning and I said to Andrew, Gee, I wonder if she has to use our compost toilet, how that’s going to be for her, because I don’t know her. (Laughter) And Andrew said, well, we should have a retrotopia badge for people who use compost toilets. (laughter) Flush toilets are one of the major wastes of water. We have a water problem on the planet. And flush toilets are one of the things that waste the most water for most people.

So we have a very elegant compost toilet — I don’t know if you used our compost toilet, Tami, but we have a painting in it, and it doesn’t smell, and we keep it well supplied with crushed leaves and so on. And I think we have a very good example of a great compost toilet that other people could emulate, but I don’t know how city people will necessarily take it. The idea is that there’s an open badge system which the Open University in England uses in which people get badges — it’s like a micro-credit system — in which people get badges for the kinds of activities that are our ancient future skills. So we’re working on it.

I think we need to do things well. I mean, if we’re going to make a compost toilet, let’s make a really good compost toilet that people can feel good about using. That’s buen vivir–the concept that we can actually live better if we live in a more simple way. You know, here I am at 75 years old and I have too much stuff. I’m beginning to realize that. So I start to give things away.

I think this is a good approach to life. We don’t need so much stuff. What gives us joy and makes us feel good inside, I think, is knowing that we’re doing something really positive in our lives. We’re doing good service. We’re helping other people. We’re acting in ways that are harmonious as much as possible. We are not creating disharmonies for other people in a negatively intentional way. And then being in this natural world in which we are completely connected. I wake up in the morning and I see the bougainvillea and I hear the chacalacas, the birds that have really big wings. They were making a lot of noise. And that’s joy. That’s where we need to go. Simple. But it doesn’t always happen. Alberto sent me a great little video the other day in which the guy said, “Is your life like a straight line, like this? If that’s so, that’s a flat line. You’re dead”. Life needs to have some ups and downs to keep it alive and interesting.

Tami: That’s great. That’s amazing. I love picturing you there. I love the buen vivir and bringing up beauty. It makes me think of when I met you and you were talking about the caravanistas and our group of earthy volunteers for the Call of the Condor, it was a very chaotic context to be organizing and people were arriving from all corners of the world.

You encouraged us to care for our appearance and embody the elegant hippie, rather than the stereotype of the dirty hippie. And you modeled that. You wore these beautiful clothes and were always very elegant in the most chaotic of circumstances.

It reminds me of my mom. She’s a farmer, a gardener. I don’t know how she does it but she’ll be outside all day, then come back inside still looking clean and fresh and beautiful. My grandpa, her father, also a farmer, was the same. Carrying dignity and beauty within every facet of life. A presence of heart, of spirit, tending to what really matters in a good way. There are so many more questions I could ask but it’s already the top of the hour and I want to be sure there’s plenty of time for Q and A.

Before we open to questions, I’m really curious about a new project for you, the Ecosystem Restoration Camps. Can you tell us in a nutshell what’s happening there?

Liora: They started with John Liu, a brilliant photographer who was hired by the World Bank about 20 years ago to photograph the restoration of the Loess Plateau, the largest plateau in China. It was at that time a completely desertified region the size of France or Belgium. And why was it desertified? Largely because the campesinos, the farmers, were taking their animals onto the plateau to eat and they destroyed all the growing plants. So the Chinese government and the World Bank paid the farmers to keep their animals off of the Loess Plateau and plant trees for about three years and offered them the possibility to own the land after they helped restore it. And as a result the restored Plateau is now a green paradise–you can find many videos about it on the Internet. This inspired John to start a movement of creating camps. He figured, well, when people go camping, they live in nature. They live simply. They do things often on a volunteer basis. So he started a movement called Ecosystem Restoration Camps, which has now grown. As I said, there are now more than 54 camps all over the planet in every continent.

A couple of the camp managers, Teryl Chapel and Leo Lauchere are on this call. This is an inspiring movement because it’s very practical, it’s all about restoration, and it includes all of the elements Andrew and I have been studying and promoting. Especially Andrew, who has been a permaculture designer for the last 40-50 years and is now into syntropics–if you haven’t heard of syntropics I’m happy to share resources. And now it’s evolving beyond just camps also into communities, because we need to go local. That’s something I’ve been stressing a lot. This has been happening here in Mexico and in Ocotlan where there’s a WhatsApp group sharing local consumption. “Do you have three kilos of avocados?”; “I’ve got mojarra (tilapia) that I’m selling on the weekend” and this kind of back and forth so the community gets built up into a very resilient and strong force in our local areas.

Tami: Thank you. I love that you’re completing with that because I’m living in the Missouri River watershed, and that’s kind of naturally weaving even here. And I’m helping people see this as a bioregion. We are finding ways to connect and interweave and localize more and more. And that’s such a hopeful thing. We also interviewed Laura Kuri and she spoke a great deal about this as well. Thank you for the links.

Liora: I want to say something about these links because Leo Lauchere is here also. He is a Gaia University Masters associate also and a good friend. I think what he has been doing in his camp and probably Hannah as well, is making an entrepreneurial business that is a recycling business as well as being a camp. So not only are they overseeing restoration, but they’re earning a living doing it. That’s one of the elements we always felt was important. At Gaia University we have always had a free course of regenerative livelihood by design to help you see how you can actually make a living doing regenerative work.

A lively Q&A session follows:

Kaitlyn: I loved everything that you were saying and it resonated with what I feel about the world. But I wanted to ask you, how do we change people’s minds about how we live and convince them to do things more sustainably? I just read an article about these guys who made a high yield battery that could power a household for 30 plus years. And the American government let it go to China because nobody wanted to invest in it. Because the investors were like–why would we want to invest in a battery that would produce power for somebody for 30 years? How are we going to make money on that? How do we change our mindset? It seems like such a barrier.

Liora: What we’ve been working on is helping people deal with their trauma and distress. Of course people need to find whatever techniques work well for them and we’ve been using re-evaluation counseling. (rc.org) Gabor Maté and Tomas Hübl are others who are looking at how we help people heal trauma so they can become more rational, intelligent, highly aware and conscious by relieving some of their distress. I think that’s an important approach because what I’m seeing is that when we are distressed we act in ways that are irrational and often destructive. And if we want to make the kinds of changes we need to make, people need to act in more supportive ways. We need to give up the myth of progress, for example. That’s a big one. It may require things getting much worse than they are now. When the Second World War broke out in England–Andrew is English–people made a 180 degree turn and gave up many things that they had been doing previously and started making victory gardens and all kinds of things. I’m not proposing that we go into war mode, but what I’m saying is that sometimes when things get very challenging, it does push people toward a better system. I’m not sure that’s a really good answer to your question, but maybe someone else has a better answer.

Tami: Here we also have Bea Briggs from the Bioregional movement who might have something to add here.

Bea: It’s more like an experience that 20 years ago or more, maybe closer to 30. I was living in Chicago and I learned about the bioregional movement, which was really interesting to me as a concept. And I thought, can it be applied in an urban area like Chicago? And I just started. That’s how I came to consensus facilitation, through the bioregional movement.

A colleague of mine in Chicago and I started just calling people together around this question–let’s figure out where we live and what’s going on here. And we’re talking about the city, the urban area of Chicago. And somehow at the very beginning, we had one guiding idea because we had no idea of what we were doing, of course. But we said, okay we’ll do this but if it’s not fun, we’re not going to do it. We don’t do it.

So we immediately eliminated bureaucracy, an official kind of NGO status, bank accounts, nothing. We didn’t charge for anything. We didn’t pay anybody for anything. We just went out and explored our bioregion and learned from each other. And then we wound up organizing an event that attracted people from all over the Great Lakes and beyond and, and connected with the much broader bioregional movement. But I think this core idea is that, as difficult as the issues are, the people who come together to do this transformational, regenerative, ecological work should be not suffering in the process. And so finding ways to make them mutually supportive and therefore more enjoyable is, I think, a seed to plant in all of our hearts and minds in how we approach doing this work.

And by fun I don’t mean frivolous. I don’t mean let’s just have a beer and forget about everything, but just make it satisfying at the human level, enjoyable. Change the discourse a little that way.

Liora: So I noticed there was someone, Deborah Charles, I think it was, is interested in eco camps and has a land in Italy. I didn’t mention that Andrew and I are now working as the coordinators of Knowledge Exchange for the ecosystem restoration camps and communities. So now we can help with Knowledge Exchange. That’s ancient future skills. That’s awesome. So, Tracy, what did you want to say?

Tracy: Well, I just wanted to say, Liora, you have just been such an inspiration to me for so long, and I know that sounds trite and cliche, but what Tami just said, it’s just I have never known a human being to really walk the talk in the way that you do that is just so broad and deep. You never cease to surprise me. And I did get to spend just a brief little few days with with Liora and Andrew and talk about Buen Vivir–I mean, with all the stuff you had going on at the time, you were still able to really just live a good life. And I loved seeing that and experiencing that. And I also wanted to share that Liora did a wonderful interview with John Lou, which you can find at the Esperanza Project. And Andrew did a wonderful story for us on his book, Dismantling the Patrix with Ecosocial Design, which we haven’t talked about, but it’s definitely worth checking out.

So just go to the Esperanza Project’s website–www.esperanzaproject.com — and put in Liora’s name and Andrew’s name and you’ll find all kinds of good stuff, in English and Spanish as well. Not all, but most of the stories are showing up in Spanish, thanks to our Spanish language editor Angelica.

Liora: Thank you, Tracy, for mentioning Andrew’s book. It’s available online. You can download it at www.leanpub.com/ESD, a great intro to EcoSocial Design, and it’s by donation, anything you can afford starting at $0. So it’s freely available and it’s got a wealth of information that I think relates to this whole question of ancient and future skills. Yes. And I just want to thank you again, Tracy, for everything you have done in Latin America, especially.

Liora: Tracy and Tami are two of my heroines. They’re amazing women. So thank you so much.

Tune into the live YouTube of the conversation here to hear the rest of the conversation with some very special “Consejo Familia” guest speakers tuning in at the very end!

- A Year of Listening, Resistance, and Hope: Reflections from The Esperanza Project - December 30, 2025

- Arts to Breathe: A Continental Act of Dignity - November 28, 2025

- “It’s not grass, it’s a milpa”: Defending Life on Avenida Federalismo - October 8, 2025

Caravana Arcoiris de la Paz Consejo de Visiones EcoSocial Design Ecosystem Restoration Camps Gaia University Huehuecoyotl Rainbow Peace Caravan