Perla has been a professional pharmacist for 22 years. Even as a political refugee living in a tent meant for weekend camping, trapped by circumstance and a cruel immigration policy, the Nicaraguan grandmother managed to ply her trade and make herself useful to the thousands of other refugees halted at the US border by the same inhumane situation.

But all that is about to change….

For years back in Matagalpa, Perla made no secret of her allegiance to the Partido Liberal Constitucionalista (PLC). The political successor of the country’s original Democratic Party, which has existed since Nicaragua became independent in the 1830s, some form of the PLC has traded the country’s top jobs with the Sandinista party since the revolutionary overthrow of the Somoza family dynasty in 1979.

Through it all, Perla earned higher degrees in chemistry and pharmacology, became a mother of three, and a volunteer counselor at her local PLC office for Youth and Women. In 2011, however, the party began to lose its grip on power, first failing to hold onto its majority in Congress, then losing the presidency. Perla continued her political advocacy, but being part of the opposition grew increasingly dangerous.

It started with her getting vocal pushback for her liberal viewpoint. Then, according to Perla, it became more difficult to get — or keep — a job if you didn’t show your support for the majority-Sandinista government.

When the Sandinistas tried to raise the official retirement age, popular protests were met with violence, says Perla. Any critique or disagreement with the party could result in physical violence, including sexual assault by the authorities, which the government did little to stop.

By2018, Nicaragua was embroiled in civil unrest reminiscent of the US-backed Contra-war era. Government-sanctioned violence led to an increasing civilian death toll, as well as documented instances of torture, the ransacking and burning of buildings, and death threats against journalists. Opposition figures argued that the government was responsible, a view supported by some international press outlets and NGOs such as Amnesty International.

On September 29th of that year, President Daniel Ortega declared that political protests were “illegal,” compelling the United Nations to condemn the action as a violation of the human right to freedom of assembly.

Then a youth group leader with whom Perla worked was assassinated. Death threats posted to Perla’s Facebook page followed. Then her cousin, who was also active with the PLC, turned up dead.

Perla fled south to Panama in April 2019. Her intention was to relocate there, where she could be close to family in Nicaragua, but far enough away to feel safe. Her son joined her, also afraid for his life, followed by one of her two daughters as well as her two grandchildren.

When a paramilitary force believed to be in league with the Sandinista government appeared, the family was forced to flee again. This time they went northward.

They had to pass through Nicaragua under cover of night, avoiding crowded urban areas. Perla didn’t dare check on her home in Matagalpa, though she longed to.

From Nicaragua, they traveled by sea to El Salvador, then by bus through Guatemala to Mexico, where the trek continued, sometimes by bus, other times on foot. They found safety in numbers, joining groups of other migrants they met along the way. They walked mostly at night from dusk to dawn; they rested during the heat of the day.

Perla, her daughter, and two granddaughters arrived in Reynosa, Mexico, just across the Rio Bravo from McAllen, Texas, in August 2019. They knocked on the door of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and requested asylum from political persecution. Though a political refugee, and hunted, Perla was bused to Matamoros. The US government left her there to fend for herself with two small children in tow.

Just one of a growing number, now in the thousands, of refugees trapped in one of the most dangerous places on Earth, Perla moved as if by instinct. She found the “free store” set up by the Angry Tias y Abuelas to secure for her family a tent, sleeping mats, bags, and clothing. Then it was time to look for a doctor. One of her granddaughters had fallen; Perla suspected a broken wrist.

She located a nascent clinic, set up in the garage space at the newly opened Resource Center Matamoros. There, Perla noticed a stockpile of donated medications. She wondered if there might be a role for her here. She offered her services as a pharmacist, handing her relevant papers over to Blake Davis at Global Response Management. Her job was to control and stock medications, keep track of expiration dates, fill prescription requests, and liaise with the Angry Tias when supplies were running low. She even trained assistants from among the asylum seekers whose numbers swelled the camp to 3,000 by the time Trump closed the border to them in March 2020.

“It has never been easy here. Mexico is dangerous and tent living is demoralizing. When the border closed, so did our frustration with the situation. Then came our desperation. The asylum courts closed. No one and nothing moved. We knew we had to wait if we wanted to cross legally. People started giving up. More and more, every day, were driven across the border by the twin threats of COVID and the Cartel.”

Throughout spring and summer, they would go to the CBP office on the bridge daily to ask for updates. “No one knows, they’d tell us.”

They’d phone the US Border Patrol regularly, “but no one ever answered.”

Then Mexico’s Instituto Nacional Migración (INM) erected a concertina-wire topped fenced, stating COVID restrictions. They said if you leave the camp for any reason — to try to cross the river, to take an apartment — you would not be allowed back in. That caged the refugees in. “But where else could we go?” asked Perla.

“Besides,” she said, taking a political stand. “If they closed the camp, there would be no way of putting pressure on the US government to end MPP.” As the stifling summer heat gave way to hurricane season, Hurricane Hanna battered the tent city. The camp and its inhabitants remained a visual symbol, hugged right up against the US border at Brownsville, of the heinous injustices wrought by Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda.

“We need to keep the camp alive to justify putting pressure on the US to end the policy,” a committed, if exhausted, Perla told me in early October 2020. “But sometimes I feel defeated, and without energy. I can’t go back to Nicaragua. And I don’t want to enter the US illegally. I have no other choice but to wait. So I pray and stay put.”

Perla and her daughter and granddaughters indeed stayed put, but they refused to be idle.

“We work to pass the time and to be of use,” she said.

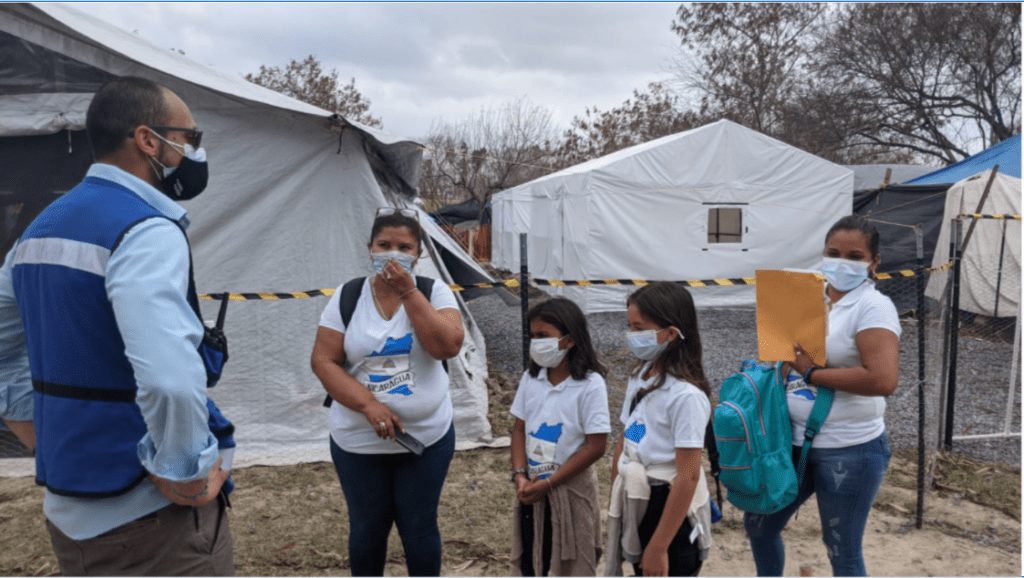

Her daughter started a camp canteen. And in addition to her work as a pharmacist for GRM, Perla also took up the job of running the Escuelita de la Banqueta, a school begun in September 2019 by Team Brownsville volunteers and closed in March 2020 along with the border.

“There are 200 kids in camp. They have nothing to do. They need a place to feel safe. They need to keep their minds active.”

By end of summer 2020, the Escuelita was back in action, with small classes, meeting in their own dedicated tent. Children and teachers all wore masks, kept their distance, poured through the hand sanitizer, and succumbed to daily temperature checks. Indeed, the only place in Matamoros that has not fallen victim to the scourge of COVID-19 is the refugee camp on the Rio Bravo levee. The number of cases ever to hit the camp could be counted on one hand, and they were all mild, proving Trump wrong again: Not all migrants come to the border bearing deadly diseases.

Perla proves, as well, that immigrants aren’t asking for handouts. Indeed, with 500,000 American souls lost to the pandemic, many of whom were front-line medical workers, the United States needs Perla right now.

She and her family will now finally cross into the US to continue their search for justice and due process under the law. She is confident they have a strong case. I will be tracking their progress in real-time as they escape the persecution of MPP and travel to the loved ones waiting for them in the US. Where they should have been all along.

UPDATE: OMG! I woke up to the greatest news this morning! No wonder I slept so soundly — Perla was freed of the bondage of MPP while I was sleeping! Last we spoke, we knew it would be soon, but we didn’t know it was imminent!

I received word from Andrea Murphy Leiner at GRM: “She crossed last night to a line of people crying and waiting to hug her and the family. I had the pleasure of being there to welcome her to the US yesterday with Sam Bishop and the team and it was one of the best moments of my life!”

Bienvenidos a los EEUU, Perla!!!!

Click here to follow Perla’s ongoing story.

Sarah Towle is an award-winning London-based US expatriate author currently sharing her journey from outrage to activism one story of humanity and heroism at a time. Read more episodes from The First Solution — including the first Survivor Story, with Gabriel — at medium.com/@HiStoryteller.

Customs and Border Protection Matamoros Migrant Protection Protocols Nicaragua