Perhaps no other Native people knows better than the Lummi the risks of megaprojects imposed on indigenous communities without consultation or consent. The tribe’s ancestral territory is located at a prime Northwest Pacific Coast shipping juncture. Battling against proliferation of toxic oil pipelines and coal ports, the heirs of Washington state’s original human settlements took note: The fossil fuel corridor slated to run from inland to the neighboring Salish Sea depends on natural wealth exploitation that is crushing age-old cultures across Turtle Island.

“The amount of impact that has damaged the air, water and land of the world around us has gotten to the point where this generation of children, as they move into adulthood, is coming to be aware that they may not survive,” says Lummi elder Jewell James. “We’re killing off all those cultures that would protect the earth, reinforcing the cultures that destroy the earth.”

Jewell James is the lead sculptor on the team called The House of Tears Carvers. The collaborative of the Lummi – or more formally, Lhaq’temish — carves totem poles to deliver messages of protection for Se’Si’Le, Grandmother Earth. The carvers, who range in age from four to 70, claim 15 totem pole journeys covering more than 60,000 miles in the past two decades. The 20th anniversary travels spotlight localities facing threats to natural and cultural heritage, tribal sovereignty, public health, and the climate.

“We’re killing off all those cultures that would protect the Earth, reinforcing the cultures that destroy the Earth.” — Jewell James, Lummi lead sculptor of The House of Tears Carvers

A totem is a being that symbolizes a concept. In the tradition of the Lhaq’temish and other Northwest Pacific Coast tribal peoples, majestic tree trunks sculpted with the symbols are monuments to history.

“We know that the public is tired of the death and destruction. We like to use a totem pole to kind of awaken something inside (with) the symbolism and stories,” James explains in a recorded prelude to the most recent trip — the Red Road to D.C. Totem Pole Journey, July 14-30.

The revered master carver had to bow out of the trip July 8 for health reasons that led to his hospitalization, but his older brother Douglas and the other carvers went on with the tour. Prayers continued for his recovery with ceremonies blessing the totem pole at 115 stopovers on the two-week jaunt to the U.S. capital.

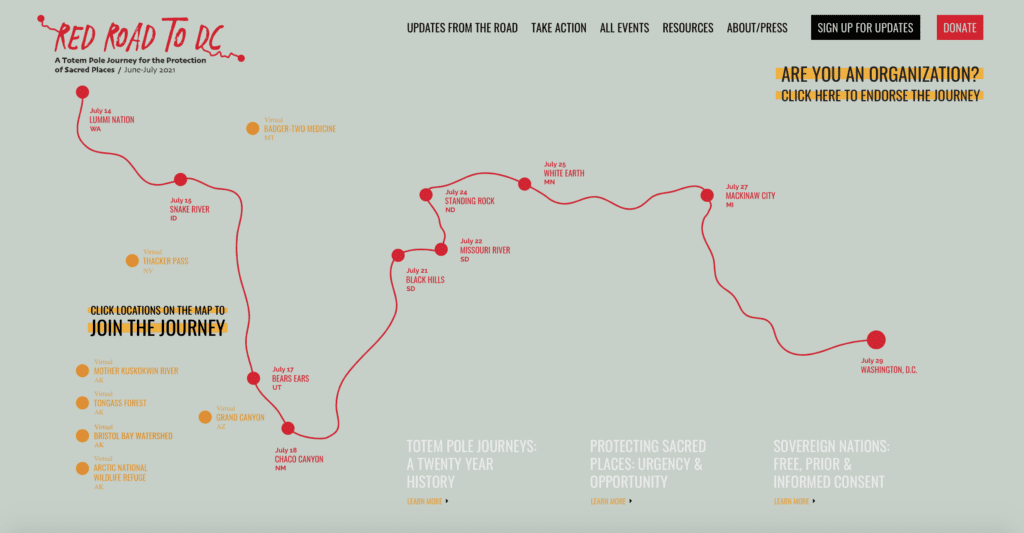

The coast-to-coast odyssey connected the dots on the 2021 geopolitical map of struggles for indigenous rights and protection of sacred sites. The tour featured the Snake River at the Washington-Idaho border; Bears Ears in Utah; Chaco Canyon in New Mexico; the Black Hills and the Missouri River in South Dakota; Standing Rock in North Dakota; and Line 3 and Line 5 tar-sands oil pipelines in Minnesota and Michigan.

The symbols on the pole address these hot-button spots to “build a social totem pole relationship where we’re challenging politicians and bureaucrats to come together and look at the science and look at the facts and make a decision to protect the air, the water and the land, and the health of the people,” Jewell James says.

Grassroots organizations all along the way paid the expenses of the carving and its safe passage to Washington, D.C. They seized hold of U.S. President Joe Biden’s Inauguration Day pledge of “regular, meaningful, and robust consultation with tribal nations.” They made use of the unprecedented ascension of a Native woman to the office of Interior Secretary – in charge of U.S. public and tribal jurisdictional matters.

Carrying a petition with 6,000 names on it, they garnered another 70,000 signatures during the road trip. The petition demands that the Biden Administration take immediate action to ensure all federal departments include free, prior, and informed consent when considering projects that affect Native lands, waters, and resources. This demand echoes international protocols incorporated in U.N. guidelines, promoted by non-governmental organizations, and applied, e.g., in Bolivia.

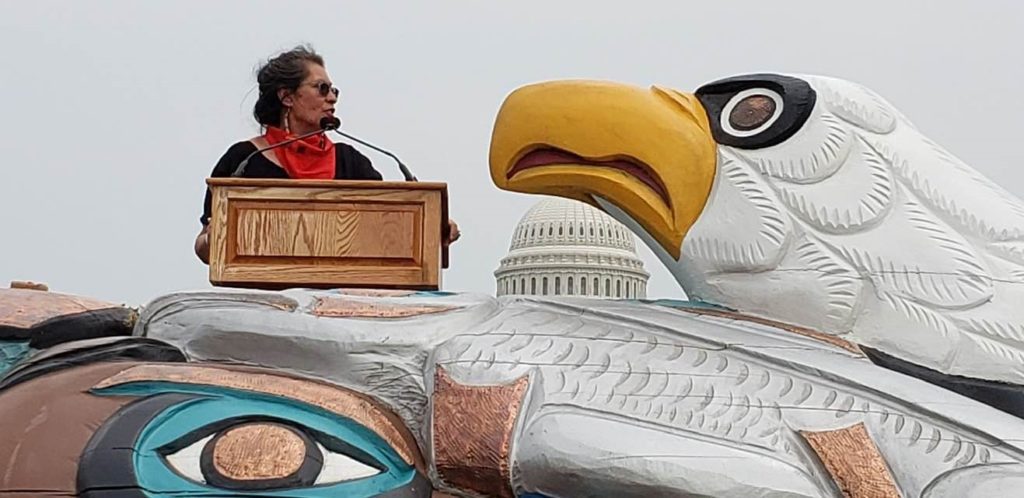

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo tribal citizen, received the totem pole during a presentation on the National Mall. Like thousands of others who witnessed the totem pole’s voyage, she laid her hands on it in a gesture of prayer. “This totem carries the hopes of everyone who has laid hands on it. It is a heavy load to carry because we know that all of our actions inform our future. I have hope for the future because it’s ingrained in who we are as people,” she said.

COURTESY / Red Road to D.C.

On the eve of this momentous gathering, Piscataway Conoy tribal leaders welcomed visitors to the tribe’s homelands surrounding the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. Beka Economopoulos, co-founder and director of The Natural History Museum, a journey sponsor, encouraged an audience at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian to go inside and view her organization’s exhibit.

The display, “Kwel’ Hoy: We Draw the Line,” is about the House of Tears Carvers totem pole journeys. The carvers launched them in what became a successful effort to prevent construction of North America’s largest coal export terminal in the Lummi Nation’s treaty-protected fishing waters off Cherry Point. The exhibit is scheduled to remain until Sep. 9, accompanying the totem pole placement outside.

On the National Mall, The Natural History Museum board member Rosalyn LaPier said, “As monuments to colonialism are dismantled across the nation, the totem pole creates a new kind of monument, one that serves to build alliances around our collective obligation to care for our lands and waters for the generations to come.” A Blackfeet-Métis Ph.D., she added, ““It also challenges us to address environmental racism and the growing climate crisis.”

Speakers reiterated the individual demands made at each of the eight hot-spots on the route. The Nez Perce Tribe is calling for removal of the lower Snake River dams and a comprehensive plan to restore salmon populations in Idaho. “Salmon in the Snake River are on the brink of extinction,” says Julian Matthews, a Nez Perce tribal member and board member of Nimiipuu Protecting the Environment. “The salmon are our food, ceremony, and medicine. So, what would we be as Nez Perce people if they’re gone? I don’t want to find out.”

The Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and Ute Indian Tribe are in court to restore the 85 percent of Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument that the previous administration of U.S. President Donald Trump removed. “Bears Ears is a place of healing,” says Woody Lee, executive director of Utah Diné Bikéyah. “The canyons hold our songs, memories, and history. This place should be permanently protected and under the stewardship of the tribes who know the land better than anyone.”

Pueblo and Diné leaders want President Biden to bar new oil and gas leases in the sacred landscape surrounding Chaco Canyon Cultural historic park in New Mexico. To date, energy companies have federal permits occupying more than 91 percent of the public lands surrounding the park. “The fight to Protect Greater Chaco encompasses the fight against the climate crisis, the fight for inherent tribal sovereignty, the fight against resource extraction and exploitation, and the fight to address the adverse health impacts on the communities who live in the region,” says Julia Bernal, director of the Pueblo Action Alliance.

The NDN Collective joined the journey when the totem pole entered unceded 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty territory on the Northern Great Plains. The non-profit organization is raising the cry of “Land Back” to reclaim the public property in the Black Hills National Forest, which the U.S. Supreme Court has declared as stolen from the Great Sioux Nation. “In opposing the ongoing desecration of our sacred land and asking for return of Lakota lands where Mount Rushmore is situated, we’re not saying anything that our parents, grandparents and great grandparents haven’t already said,” notes Nick Tilsen, NDN Collective president and CEO.

Turtle Island’s longest river, the Missouri, is the source of life for 20 million people, according to calculations of Ihanktonwan (Yankton) Dakota leaders. The Ihanktonwan Treaty Committee, Yankton Sioux Business and Claims Committee, and the Brave Heart Society are enlisting all 28 river tribes in a new treaty to protect the rights of the river. The campaign seeks to use state-of-the-art legal tools to enforce ancient traditional relationships that recognize water as a living relative.

“The only agency that is calling the shots on this river is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. That is a continuing one-stakeholder threat to our river as she is indeed a sacred traditional cultural site and always has been,” says Faith Spotted Eagle, treaty committee chair and Brave Heart Society grandmother. “What impacts the land and water impacts Native bodies and spirits, known as physical and spiritual trauma,” she warned.

Upriver is the scene of the 2016-2017 standoff between the Dakota Access Pipeline’s militarized police force and grassroots water protectors, whose prayer camps supported tribal governments’ lawsuits to halt the private hazardous materials infrastructure. Today, the Standing Rock, Yankton, and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes continue to face the Corps of Engineers in court to stop the oil-flow in the line built a half-mile from a tribal drinking water intake.

“The fact that half a million gallons of oil continues to flow under the Missouri River is a violation of our treaty rights and poses a serious risk to the health of our people,” says Charles Walker, Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council representative. “We urge President Biden to take action to shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline. If he is to hold to his promise of being a climate leader, he cannot continue to support the pipeline. If he is to uphold the obligations of the federal government to the people of Standing Rock, whose ancestors ceded lands in exchange for the promise of reserved fishing, hunting, and water rights, he must shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline.”

Construction of Enbridge Energy Inc.’s Line 3 tar-sands crude pipeline is drawing the same type of grassroots resistance at the Mississippi River Headwaters. Hundreds are being arrested for civil disobedience, while Anishinaabe tribal governments seek court action to thwart corporate operations. “My people have lived here for 10,000 years,” says Winona LaDuke, executive director of Honor the Earth. “Now a Canadian company wants to come in and threaten our waters and our wild rice. Just one spill would devastate our waterways. It’s time for President Biden to finally step up and take action to stop Line 3. His inaction is putting money in the pockets of Canadian billionaires who want to profit off of running poison through our treaty-protected territory.”

Further east, Enbridge Energy Inc.’s Line 5 tar-sands crude pipeline is operating through the U.S.-Canada boundary waters in the Straits of Mackinac, despite Michigan state’s denial of a permit renewal request. Bay Mills Indian Community, as a signatory of the 1836 Treaty of Washington, reserves the right to fish, hunt and gather in the Straits of Mackinac and the surrounding region. Whitney Gravelle, tribal executive council president, says the pipeline creates a treaty rights issue. “Our Anishinaabe teachings, our creation stories, our history here are all tied to the Straits area,” Gravelle notes. “It is literally one of the centerpieces for cultural contact and interaction for thousands of years.”

The Red Road to D.C. also highlighted struggles off its path, with virtual events, including those in Alaska at the Mother Kuskokwim River, Tongass Forest, Bristol Bay Watershed, and Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; as well as Thacker Pass in Nevada, and the Little Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.

Natural resource extraction, climate change and “unbridled development” are the main threats to indigenous land, according to Caddo Native Judith LeBlanc, director of the Native Organizers Alliance, sponsor of the Red Road to D.C. project. The non-profit calls on the federal government to: “Recognize the traditional, legal, and inherent rights of Native nations and Indigenous peoples to protect sacred places.”

Organizers were careful to clarify that the Americas’ epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous relatives, its withering history of boarding school child abuse, and its immigrant concentration camps are the direct results of disenfranchisement. Jay Julius, president of journey co-sponsor Se’Si’Le, noted that the Endangered Species Act may work to stop drilling, but the totems on the pole indicate the potential for an “endangered peoples’ act.” The Se’Si’Le mission is to reintroduce Indigenous spiritual law into the mainstream conversation about climate change and the environment.

Red handprints painted on the totem pole are the emblem of the crusade against forced disappearances. A kneeling Earth grandmother image carved into it appears to pray with a granddaughter, both holding gourd rattles. “Seven Tears of Trauma,” each representing a generation, are engraved between the figures. One of the tears doubles as the child’s rattle – to stand for intergenerational trauma. In front of the kneeling image is a “Mexican Child in a Cage,” a reference to state detentions and trials of unaccompanied indigenous minors trapped while crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

National Congress of American Indians President Fawn Sharp reflected on the culmination of the journey. Her delegation met with lawmakers, Haaland, and U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry. They discussed the role of tribal nations in international climate negotiations. NCAI is a partner in the IllumiNative network, which co-sponsored the journey.

“The day ended with an indescribable event of unity, strength, vision, and healing, as we welcomed the House of Tears totem pole to Washington, D.C.,” said Sharp. “At the conclusion, a bald eagle circled high above us. We felt the powerful spiritual presence and strength of all our relations coming from all four directions and we humbly accepted the call to action to protect our invaluable and precious sacred sites. We honor and thank master carver Jewell James for his vision, hard work, and infinite generosity of spirit and strength.”

[simple-author-box]

- Clemency for Lakota icon Leonard Peltier called ‘moral indictment’ - January 21, 2025

- Lakota tribes, grassroots close ranks to defend Black Hills watersheds - January 21, 2024

- Native ‘hempsters’ follow global cooperative example - August 30, 2023

Jewell James Laguna Pueblo Lummi Native Organizers Alliance totem carving Turtle Island