Lawrence, Kansas, pop. 96,369, may seem an unlikely epicenter for intergenerational healing of the deep scars left behind by the legacy of government boarding schools for Indigenous children. But thanks to the leadership of one of those former boarding schools and other community organizations, the city is making major strides on behalf of Indigenous communities everywhere.

Haskell Indian Nations University, based in Lawrence, is a big part of the reason why. Haskell was founded in 1884 as a residential school for Indigenous children but has evolved into a federally operated tribal university. Today at Haskell a jail and a cemetery with over 100 graves of children are still visible, a harrowing reminder of the evils of U.S. Indian boarding school policy.

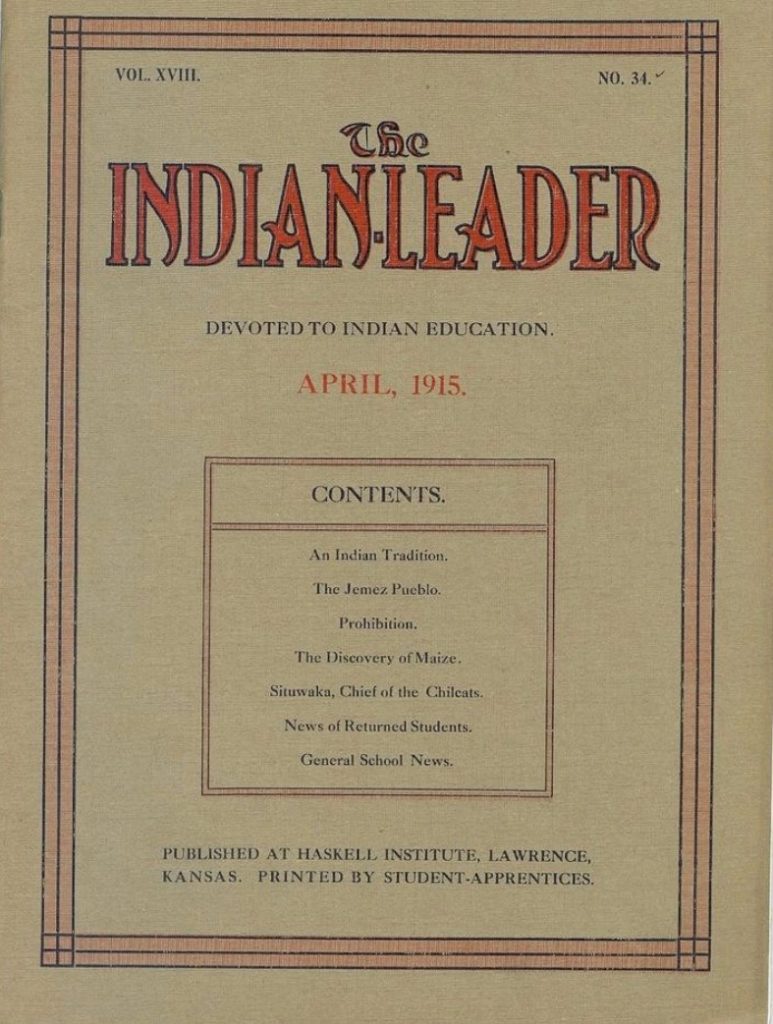

Despite playing a role in the structural and systemic violence against Indigenous families, Haskell early on showed support for its students, especially its student journalists, publishing the first Native American school newspaper.

The Indian Leader, started in 1915, is an award-winning journal that continues today. After the 1930s, big changes came to Haskell. The school became a center for the American Indian Movement and changed its mission, dedicating itself to promoting “Indigenous rights and leadership through education.” In the 1970s, Haskell became a junior college and in 1993, a university with associate and bachelor’s degrees. Each semester, over 1,000 Indigenous students attend Haskell. The student body represents 140 Indian tribal nations and Alaskan Native communities.

Many Haskell students stay in Lawrence after finishing their studies, like graduates of the University of Kansas, the flagship state university located less than a mile away. Former Haskell students form a dynamic Indigenous community in Lawrence. However, many members of the Indigenous community need services and support that are no longer available to them after graduating or leaving Haskell.

A new Indigenous Community Center (ICC) of Douglas County formed in April 2021 to meet these needs. The ICC functions as an independent organization, working jointly with The United Way. The ICC will be a vital resource to build bridges between Haskell Indian Nations University and the broader community of Douglas County, which includes the city of Lawrence. The ICC initiative developed as a response to the gaps and needs that surfaced during the pandemic to improve the lives of over 4,000 Indigenous individuals residing in Lawrence, which has not had an Indigenous community center in nearly 15 years, since the Pelathe Center closed.

The need for such services has been high, particularly with the painful re-emergence of the boarding school issue in the public eye. Particularly disturbing is the fact that more than 1,000 bodies were found in just three Canadian residential schools. This creates fear in Native American communities and among their residential school survivors and descendants. More children undoubtedly will be found in the more than 700 Indian residential schools that operated in the United States and Canada. U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), the country’s first Indigenous Cabinet member, has called for a federal investigation to uncover the painful history of residential schools. The investigation provides for the continued search for bodies in Native American boarding schools and the return of Indigenous children’s remains to their tribes. Haskell is part of this DOI initiative.

The remains of nine Rosebud Sioux Indigenous children were found at the Carlisle Indian Boarding School in Pennsylvania, journeyed home and were laid to rest in their ancestral Lakota lands. Their relatives gave the deceased a proper burial, with their remains wrapped in buffalo hides.

A recent press release by the Interior Department claims that boarding schools today, which continue to function through the Bureau of Indian Education, have changed and now embody goodness. The schools aim to empower Indigenous students “by providing them with a quality education and an avenue to practice their own spirituality, languages, and cultures.” Indigenous education also is recognized as an antidote and a way to move forward.

Indigenous Community Center Responds

Following the emotionally devastating news about residential schools, the ICC sprang to action. The ICC board members planned the center’s first support activity for the community on July 8: “The History of Beading,” a free event at Haskell Indian Nations University Sacred Grounds on Pawnee Avenue. The ICC welcomed everyone in Lawrence to connect in a safe space, so that community members of all ethnicities and cultural backgrounds could come together to have meaningful conversations and learn. The Lawrence Journal-World published a story on the history of beading and announced the upcoming event. A mixed crowd of about 40 Native/non-Native community members attended.

Board members Monique Mercurio and Krystle Perkins, from Kansas City, talked about the history of beading. Mercurio shared her childhood memories of staying up late beading with family the nights before powwows, and she explained that beading is a sacred practice and a form of prayer, which most Lawrence residents did not know. Krystle Perkins discussed her mixed-Indigenous ancestry, what being indigenous means, and how beading is key to her identifying as Chickasaw. She displayed a collection of traditional Chickasaw collars.

The ICC is initiating a new program, called “We are still here,” to provide various spaces for healing. ICC Board President Robert Hicks (Pyramid Lake Paiute) is writing an introductory video for the “We are still here” program. He is planning physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual support services and collaborations. Some of the ideas include meals; Native games for exercise; talking circles and hotlines for therapy; and music, art shows, poetry slams, round dances, and prayer sessions.

Residential School Trauma

More than 1,000 undocumented graves of children in Indian residential schools were recently discovered through new subsurface radar technology, exposing the traumatic and violent legacy of boarding schools. Beginning over 150 years ago, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children in Canada and the U.S. attended boarding schools controlled by the federal government and the church. Here, children suffered emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and died, and then they were placed in mass and unmarked graves. Many suffered from medical neglect and malnutrition. Infectious diseases spread rampantly between children living in crowded conditions, and children with illnesses were often sent back to their families, adding to the spread. Other children were murdered or died trying to escape.

Indian residential schools’ long-hidden part of Canadian and U.S. history is finally coming to light. Children were abducted from their parents and communities and forced to live in residential schools. The main objective of the schools was to assimilate Native American children to the settler-colonizer’s Anglo-Christian ways. Children were punished and beaten for practicing their culture, religion, and language. Indeed, Indian residential schools contributed greatly to the loss of Indigenous languages and linguistic diversity in the Americas.

As Indigenous peoples process these emerging and sinister news stories, the bigger question emerges. How can they heal amidst this lingering re-traumatization? The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. believes healing will not happen until the U.S. government becomes accountable for its policies of genocide and ethnocide (the killing of a culture) toward its Indigenous peoples through boarding schools.

Interview with ICC Board President, Robert Hicks

ICC Board President Robert Hicks (Pyramid Lake Paiute) is writing an introductory video for the “We are still here” program. I emailed Robert Hicks in July and asked him the following questions:

LH: What is the position of the ICC on the recent discoveries of children’s bodies at Indian residential schools?

Robert: Our position is a supportive one. The boarding school era was a very traumatizing time for a lot of Indigenous families. I myself am a third generation boarding school survivor and every new discovery they make reminds me of how easily that child could have been a family member of mine. The ICC wants to extend support to any Indigenous family affected by the situation and urges organizations working with Indigenous people to make active efforts in the recognition of the trauma boarding schools have done and to recognize how colonization has affected, and still affects, Indigenous people today.

LH: How have these discoveries affected Haskell and the Lawrence community?

RH: Conversations are being held by all the organizations associated with Native American people on how to approach the boarding school conversation. With Haskell being a part of the early boarding school era, people of Lawrence need to recognize that we have a boarding school gravesite right here in Lawrence. At the Haskell Museum they display small handcuffs for children. This is a huge indicator of how our people were treated, and ignorance is no longer an excuse. Conversations need to be had in an understanding and caring manner as colonization affects us all. History is not our fault, but it is our responsibility.

LH: What impact will the “We Are Still Here” program that serves graduates of Haskell make for the Indigenous community of Lawrence, Kansas?

RH: The program will have an impact on the Lawrence Indigenous community. It will provide a space for people to work on their emotional, mental, physical and spiritual health. This holistic approach is geared towards individual healing as we are all at different stages of the healing process.

Healing will begin once recognition is made. Recognition in the families affected, and recognition in society.

Hicks signed off his email correspondence with this message: “Poowa Poowa”/”Blowing Blessings”, along with his tribal affiliation and pronouns. Other ICC Board members include two-spirit Monique Mercurio (Dine’ and Ohlone Costanoan), Krystal Perkins (Chickasaw), and non-Natives, Leah Weseman and Laura Herlihy. The Ad-Hoc Committee member Freda Gipp (Apache) especially has guided the group; and Lori Hasselman (Shawnee and Delaware) has helped with media. A new generation of Indigenous community leaders has emerged with a sense of justice and a new world vision.

Laura Herlihy is an anthropologist, author, and lecturer at the University of Kansas Center of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. She has worked mainly with the Indigenous Miskitu people of Honduras and Nicaragua. She is a board member of the Lawrence Indigenous Community Center.

- Healing the Boarding School Wound in Kansas - September 6, 2021

Haskell Haskell Indian Nations University Indian Boarding Schools Lawrence