It’s a long way from Buenos Aires to Panama City – and the distance is not just physical. When Hernán García made his first journey to the country in 2011 as a young film student, he was captivated by the natural beauty and the cultural diversity of the country. He returned at every opportunity, and soon found himself caught up in the conflict over the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam. His 2018 film Tabasará, official selection for the Bannabáfest International Film Festival for Human Rights in Panamá, chronicles the fight of the Ngäbe-Buglé people to save their sacred river and their way of life.

García soon discovered, as I did, that while the Barro Blanco case is emblematic, it is far from unique, with hydroelectric dam and mining conflicts playing out over and over again throughout the country and indeed, the entire continent. What he learned inspired him to begin work on a new film, “Something About the Water.” I caught up with Hernán recently to find out more about him and his work.

For more about the Barro Blanco case, see our 2017 story, A Wall in Their River, and a followup earlier this year, Indigenous Communities Appeal to the UN to Help Rectify an Ethnocide.

Esperanza Project: It’s obvious from your work that you have a great love for the people of Panama. Tell us a bit about your history with Panama – how it started, what caught your attention, why did you decide to devote so much effort to representing their stories?

Hernán: It’s true. I love Panama and its people, it’s a spectacular country. I’ve been there six times and have traveled extensively. It’s magical what happens to me. I love their rivers, their seas, their mountains, their people. The Panamanian campesinos and indigenous people have found their way into my heart.

When I studied film in Buenos Aires, I met some Panamanians and became friends with two of them, who returned to Panama, so I decided to visit them. I started to go in 2011, seduced by its beaches, its climate, its landscapes, its people and its fiestas, but two things really intrigued me: the Caribbean Sea and the natives.

The Caribbean was beautiful and pleasant. And the indigenous people really had an impact on me. I discovered their culture, their worldview, their religious ideas, their humility. It was transformative for me.

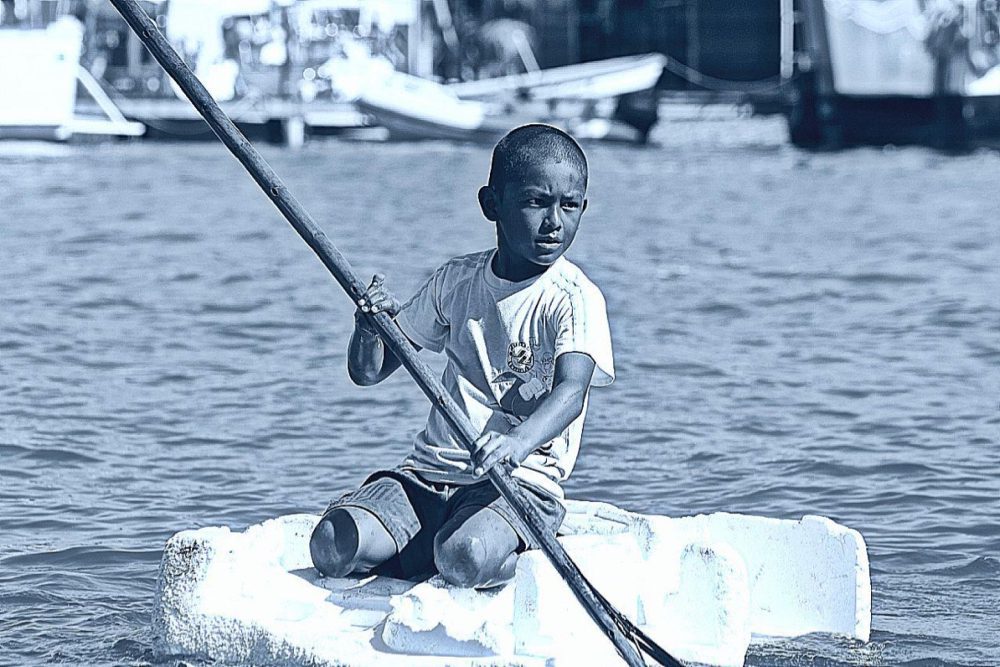

I had the opportunity to visit Guna Yala in 2011 and the Ngäbe Buglé region in 2012. I bought a camera and started shooting. What most caught my attention was the water issue. Populations without access to water, entire neighborhoods flooded, farmers suffering from lack of drinking water. Islands that were sinking.

I quickly became immersed in the socio-environmental issues almost without realizing it.

Esperanza: When did you find out about the situation in Barro Blanco? When was the first time you went, and what caught your attention? How did you make the decision to make a documentary?

Hernán: The first thing I filmed was a short film about a Ngäbe reading and writing program, with those two friends, fascinated with going to see Kiad, a place where nobody had ever filmed before. The experience was unforgettable in many ways.

But more unforgettable was when we left the village and headed back to the Inter American Highway to return home and we met with a large protest against dams and mining in the region. On Feb. 3, 4 and 5, 2012, the riot squad killed two demonstrators: Jerónimo Rodríguez Tugrí and Mauricio Méndez and there were dozens of people injured and detained.

I was in Tolé and the worst happened in San Felix, a few kilometers away, so I was safe, although it took me hours to get out.

From then on, my perception of environmental issues changed. It was a slow awakening that today is fully entrenched. They are coming for the water. At that moment I understood.

Esperanza: How has daily life in the community changed since you first visited?

Hernán: The life of the community changed drastically.

They went from having a beautiful and clean river to washing and refreshing themselves in a natural way, washing clothes, fishing, washing vegetables, and a productive food forest that provided their sustenance, herbal medicine and income, to having a dirty, polluted river, flooded lands, the fish gone, the forest dead, destroyed.

Many people left because they did not have any way to survive. Those who remain there out of sheer moral strength and a sense of belonging only have access to a water source that is growing smaller, that comes from a spring on the mountain and that they pipe to the community through a tube.

There are many mosquitoes in the place, something that did not happen before; there are no birds to control them anymore. It is very difficult to sleep there, and the children suffer. The reservoir is surrounded with thick of mud, making it dangerous and difficult to get around and leave the community. The most striking thing is silence, a place with very little life. A true ecocide brought about by GENISA and its henchmen.

They transformed an ecological and self-sustainable community into a community with deficiencies, hunger, thirst and disease, submerging it in capitalism, when they are not prepared for it.

If I miss Tabasará as it was before, I can not even imagine what they feel at the moment.

However, the Miranda family and many other residents resist, trying to reverse this. Beyond the impotence that they can sometimes feel, they will not give up, they will not abandon their home, and neither will we.

Esperanza: Tell me a little about the process of making this movie.

Hernán: I differentiated the urgent from the important. In my first visit to Kiad I had gone to discover and show their culture: what they ate, to whom they prayed, how they related to each other and the land. In the second, two years later, I went for a more urgent reason: Their river. The Barro Blanco hydroelectric project had been approved and was already being built. I kept documenting through the years, I returned in 2015 and twice in 2018, five times in all.

I was documenting the process of deterioration suffered by a community like Kiad, when installing a project as large as the Honduran company GENISA was doing with the support of European banks, with falsified environmental impact studies and without any consultation with the population.

The devastation is great and the landscape bleak. The Tabasará is contaminated and the pain is immense. It was a beautiful and clean river. What they did is an ecocide.

Then there is the editing process, which is the most fascinating and solitary of all, where the magic happens. This film was edited for the first time in 2015 and then had more than 20 reissues. I work in my house in Buenos Aires, with a lot of patience, for hours, correcting and visualizing, showing it to people to see their reactions … and so I was putting it all together, like a puzzle. At times I abandon it, like now, because I don’t know what to touch anymore and I’m afraid to ruin it. Then I publish it, I send it to festivals, I present it in Panama like last year in Bannabafest or in Buenos Aires like I will in a few days.

I think it has begun to fly; it’s about time the world finds out what is happening there.

We must stop this project.

An indigenous community without resources can not beat the big corporations, especially if they have the support of political, judicial and media power.

This issue is invisible, and it cannot continue like this.

Tabasará is a living documentary. I will continue going to film and I will continue editing it for many years, if I can. However, the current version represents me totally and for now it will remain that way, until there is news.

Esperanza: What did you learn during the course of this work?

Hernán: I learned that you have to fight for your dreams, that even if you work in the most absolute loneliness and feel that it’s impossible, never give up. You always have to insist, whatever happens. Independent film is like that. You have to go for what you want. I don’t believe in excuses, I got tired of them. It doesn’t take a technical team nor a script, nor do you need a lot of money. You have to push yourself to film alone, like I do.

I learned that the subject of water is critical and that I can be one of the bridges to help this information to spread. I learned that I can contribute a grain of sand to open someone’s eyes or achieve greater empathy for these peoples who are violated in their rights, evicted by the state.

I learned to be modest, humble, to understand how difficult it is sometimes to access some places and even harder, to live there.

Esperanza: What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in making this movie?

Hernán: In the beginning, the Panamanian heat is something complicated for someone from the south. The sun is very strong and the humidity is very high, especially for filming. So I decided to shoot only in the early morning and at sunset. I don’t like to film at night and I do not have production equipment for that.

Another challenge is loneliness; sometimes you need help, but things are like that … and at the same time I like to not depend on anyone to achieve my goals.

Other challenges would be the cultural clashes that sometimes exist but which I got used to, like walking in the mud, wading or swimming across rivers, traveling in mini buses crammed in like cattle. Withstanding the intense cold of long-distance buses, adapting to the food, traveling with little money — those are a few, but they can be overcome.

Esperanza: What surprised you along the way?

Hernán: I was surprised by the warmth of its people, the hospitality of the Panamanian campesinos and indigenous people. And of many city dwellers too. I have many friends. It also amazes me how alike we seem at times. The landscapes of Panama are amazing, they have a lot of green, they have a lot of water.

It surprises me and at the same time not, the government negligence in the whole country. Broken streets and sidewalks, somewhat dangerous mountain routes, polluted rivers, garbage everywhere.

A striking contrast, beauty on the one hand, garbage on the other.

Esperanza: What message would you like people to take away from this movie?

Hernán: The main idea of Tabasará is to touch hearts, generate awareness, achieve empathy in society, especially the city. To spread the problems of water, the indigenous and campesino issues, to show Panama to the world, with its beauty as well as its problems.

Telling the story of those displaced by the system, those forgotten by the state, being the connection between these populations and the rest of the world, without needing the media corporations, being direct and profound with the message.

Esperanza: What has been the response to the movie so far?

Hernan: The movie had several stages. The main objective was that the people of Kiad should see it at first. Then it was presented in some places in the Panamanian interior and the University of Panama at the Bannabafest 2018 Festival. Now I am presenting it in Argentina in a few days and they are going to project it in Nicaragua, with the date to be confirmed. I hope to show it throughout Latin America and the world. That is my dream, that it becomes something more massive and that they will set their sights on deactivating Barro Blanco — and that the sun will rise again for the Ngäbe Buglé people.

Now is the time for this movie to take off. Perhaps the dream will be fulfilled.

Esperanza: Tell me a little about your current project: “There’s something about the water.” Why did you choose this title?

Hernán: This title occurred to my companion Lucy, because I am always documenting these themes and it is a subject that I am passionate about and concerned about.

Since I went to Panama for the first time more than eight years ago, there was always something happening with the water.

Positive and negative. It is a tool of manipulation, exercised by the great powers over the most vulnerable social sectors. And this injustice is intolerable. Water is a right, it is not a commodity, but in the halls of power it is not understood that way.

It is my second feature film: There is something about the WATER. It is an ethnobiographical, social, anthropological and cultural documentary, which awakens consciences. They come for the water, and something must be done. It is the most personal, perhaps, telling my experience in Panama in the first person and portraying from different points of view this subject — for example, the subjugation that the hydroelectric plants impose on the communities that depend on the river, the scarcity of water in the more marginalized urban areas, the flooding in deprived neighborhoods, rivers and seas contaminated by garbage and the contrast of the great consumption that there is in the cities, besides the waste of the companies and the users.

Esperanza: It’s obvious that there is a serious problem with the imposition of hydroelectric plants in Panama. There is also a need to generate electricity. What would you like people to take into account on the subject?

Hernán: I think there are several things we can do. Stop looking away, for starters. Each one from his place can always collaborate. I make documentaries, but there are many ways. Using less plastic, taking care of the water, fixing the leaks (above all the underground ones), enforcing the human right to water and sanitation. Create laws that allow everyone access to drinking water. Building wind farms, using more solar panels.

The businessmen with their bad management of energy, not using so many lights and so many air conditioners, are a few things that can be done.

But the fundamental thing is to inform oneself, make oneself aware and make others aware.

Esperanza: When do you expect to release this movie?

Hernan: I still don’t have a definite date, but I believe that it will be this year, closer to the last quarter.

It will depend if I get a sponsor to suport it. A co-producer. But if no one appears, I’ll do it all the same, I’m not going to depend on that, only maybe it will take a little longer. I have about a third of it filmed and I am making progress in editing, but I still need to continue filming and editing. It is a very comprehensive and complex topic.

Esperanza: Can you talk a little about your personal process in your work as an Argentine filmmaker in Panama? What have the people of Panama taught you? What have you learned about yourself and about life on the road?

Hernán: I learned a lot at this time, from life in general. It was a revealing time.

I could channel that desire to collaborate that I always had to make this world a better place to live and at the same time reaffirm that feeling of having found my passion in life. Telling stories of ordinary people, giving voice to the oppressed. My camera and I, in nature, observing, investigating, learning, making friends, eating whatever there is, sleeping wherever I can, playing this beautiful game that is being the bridge between two worlds, which in reality is the same world.

In this process I made many new friends, and I have stories to tell. I enjoyed, I suffered and I lived to the fullest every trip.

Along the way, I had some losses that also changed my way of seeing life.

Esperanza: Can you give a brief overview of some of your earlier work as well?

Hernán García is the director of six films about Panamá, including “Río Cobre” (14 min.), about the successful fight to stop an open pit mine in the Ngäbe Buglé comarca; and “9 Enero, Medio Siglo Después” (January 9, half a century later, 22 min.), about a series of protests in Panama over U.S. control of the canal zone ending in 24 dead, now called “Martyrs’ Day” in Panama. Both films were awarded at Panalandia 2018, as the best documentary for the public and Special prize of the jury respectively.

Hernán: Other works I did a few years ago include “Río Cobre” (14 min) on the struggle of Larissa Duarte and her father Genaro, together with the support of the community, to keep the Río Cobre free of hydroelectric dams, in a struggle unequal against businessman Eduardo Vallarino and Los Estrechos SA in the province of Veraguas; and “January 9, Half a Century Later” (22 min), is a documentary that portrays the events that occurred on January 9, 10 and 11, 1964 in Panama City, a student march in which there were hundreds of injured and detainees and 22 Panamanians killed for defending the Panamanian sovereignty of the US overcrowding in the Panama Canal zone, and a march held 50 years later where these students, already older adults, meet again and tell their story.

Both films were awarded at Panalandia 2018, as the best documentary for the public and the Special Prize of the jury, respectively.

I have another short film called Trapiche ready, which tells how the cane is scraped and how important it is for a family in the 21st century to maintain the family tradition.

And “El Otro Portobelo” is already available about the other side of that trendy tourist city, showing a bit of its Congo culture, but focusing on two interwoven stories, the story of a visual artist and that of a music school for teenagers and children (24 minutes)

I also do institutional, music or poetry concerts and experimental videos.

Everything is available on my website, www.hernangarcia.weebly.com, from the YouTube platform.

There are also the Facebook fan pages, where there is more information: Tabasará – Documental, Hay algo sobre el AGUA Documental Panamá, El Otro Portobelo Documental Panamá and Hernán García Documentalista.