It’s a technology that’s been all but abandoned in wealthy countries, where costs began outpacing benefits decades ago. Yet a global boom in major dam construction, mainly in developing countries, is currently underway, with an estimated 3,700 now under construction or in the planning stages. Latin America is ground zero for much of this development, with nearly 400 slated for the Amazon region alone. Booming populations need power and water, and hydro dams can provide both.

Leer este artículo en español aquí.

Megadams have fragmented and transformed more than 60% of the planet’s rivers, choking off the flow of water, and life. In 2000, according to the World Commission on Dams, there were 47,000 large dams built in the world; that is, more than half of the world’s rivers were dammed, causing the displacement of 80 million people. In Mexico, according to the 2012 report, Dams, Rights of the Peoples and Impunity, more than 4,200 dam projects have been built in Mexico alone, causing the displacement and forced eviction of more than 185,000 people from all over the country.

This article is part of a series on the impacts of megadams in the Americas. Read more here.

Critics warn that the costs far outweigh the benefits, especially in an era of climate change, when unprecedented droughts followed by torrential downpours make these structures more vulnerable. Hidden costs like biodiversity destruction, generation of greenhouse gases, loss of life and livelihoods and the devastation of human communities are seldom taken into account – and they make a powerful case that this supposedly “green” form of development is actually anything but.

An emblematic project currently in the spotlight in Western Mexico is the El Zapotillo System (which includes, besides a dam with the same name, an aqueduct starting there which ends in Leon, Guanajuato and another dam: El Purgatorio-Arcediano) to provide water to the cities of Leon and Guadalajara, Jalisco.

Maria González Valencia, activist and water protector of the Mexican Institute for Community Development (IMDEC, for its initials in Spanish) and previously with MAPDER, the Movement of Dam-Affected People in Defense of the Rivers. She’s worked long enough on this issue to see the huge economic, environmental and social costs they generate.

“We need to fight against an obsolete technology that in other countries is no longer regarded as an option,” she said. “On the contrary, they have virtually stopped building them in most European Union countries and in the United States. Dams that already exist in those places are now being dismantled and their rivers restored,” states the community leader, who has been at the forefront of the fight to save the villages of Temacapulín, Acasico and Palmarejo against inundation by the mega project.

González cites the seminal 2000 World Commission on Dams report and many others in her condemnation of the wave of hydro dam construction across the Americas.

“In Latin America and specifically in Mexico, this continues to be an inviable alternative from the perspective of an integrated water management, since huge engineering projects and hydraulic constructions are involved without considering social and environmental impacts. Even in economic terms they’re a poor alternative, because as time goes by, they tend to double or triple their cost.”

The WCD report points that “in too many cases an unacceptable and often unnecessary price has been paid to secure those benefits [related to the dams], especially in social and environmental terms, by people displaced, by communities downstream, by taxpayers and by the natural environment.”

This is the case in El Zapotillo, said Gonzalez. “After 14 years fighting against El Zapotillo Dam, it’s beyond proven that it’s an expensive alternative which has implied scandalous processes of corruption.”

Journalist Sonia Serrano echoes Gonzalez’ criticism in El Zapotillo: Omissions, Errors and Corruption, a 2018 story for the newspaper NTR Guadalajara. She states that the aqueduct from El Zapotillo to Leon got authorities facing legal issues “First, because of the corruption over the contract with the Spanish construction company Abengoa and Jalisco, the state workers’ money was deposited to try to save the constructor from its economic crisis; however, it was not enough to help the constructor to set even a single pipe.” Around $604 million pesos, or USD $31.5 million, was taken from the state workers’ pension fund as an unsuccessful bailout of the project.

Besides Abengoa, two other contractors walked away with an additional $1.4 billion pesos (USD $72 million), according to Agustin del Castillo of Milenio.

State governments from Jalisco and Guanajuato maintain that, since the dam is almost finished, it should be used to provide water to both territories. Gonzalez counters that in terms of the whole system, it’s less than half finished: the dam is 87 percent finished, but the planned 140-kilometer aqueduct is only 5 percent done, and El Purgatorio-Arcediano dam is stalled at 30 percent after 15 years.

Gonzalez finds it unacceptable that the costs of the project rose over 350 percent during this period without even halfway finishing it. In 2006, at the beginning of the project, the government put the cost at $7 billion pesos (USD $350 million); costs have now risen to $35 billion pesos ($1.7 million USD). If this project is finished, it would cost an estimated $71 billion pesos (almost $3.6 billion USD).

Jalisco Gov. Enrique Alfaro, once a defender of Temacapulin, now supports the dam, and questions the motives of opponents.

“Who is behind the idea of doing nothing regarding our water issues? Who has an interest in that? That’s what we must have in mind,” said Alfaro in July.

But González sees things differently. “It’s a project that will be under construction for 16 years; it’s been 14 years since they started. The lifespan of this type of dam is 25 to 30 years. Under what kind of financial or economic logic does it make sense to build a project that will take half its life to build? At what cost? What are the consequences?” she questions.

The dam violates Human Rights

Building this type of mega project violates the fundamental rights of the people and their communities, and the rights of nature, as well, as González and IMDEC have documented.

“So far, we have counted 20 rights violations, such as the right to information, the right to consultation, the right to participate; that is, the three fundamental rights previous to the approval of any mega project like El Zapotillo have been violated.”

But there are other violations, as well, such as the forced displacement that happened in Palmarejo village.

“If those people made the decision to move or sell, it was under threat. The companies and the government didn’t organize consultations, there wasn’t accurate information and there were no processes of participation. Thus, they forced people to move through strategies of harassment and menace.” This case is documented in Recommendation 50-2018 of the State Human Rights Commission of Jalisco (CNDHJ, for its initials in Spanish)

The recommendation was issued against Jalisco authorities “for the violations of the rights to legality and legal security, to property, to housing, to preservation of the environment, to the common heritage of humanity, to development and health, caused by the National Water Commission (Conagua, for its initials in Spanish) and local state authorities from Jalisco and Guanajuato for their attempts to flood the communities of Temacapulín, Acasico and Palmarejo.”

In the eyes of the activist, there are other rights affected, such as “the one for a healthy environment. Despite the pause in construction now, it has advanced and there is evident devastation of the environment,” she said.

Megadams vulnerable to climate change

Monti Aguirre, Latin America coordinator for International Rivers, has been following the El Zapotillo case since the beginning, and says it’s typical of what’s been happening around the world. She worries that with the rush to respond to climate change, governments and development banks are seizing on the “false solution” of hydro dams, with sometimes catastrophic results.

“Something that needs to change is this misconception that dams are clean,” she said. For one thing, they eliminate an entire carbon sink – the forest – which then decays under the water and emits significant amounts of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases. For another, there are also severe impacts on biodiversity and water quality throughout the watershed.

“The other thing about hydro is that it’s very vulnerable to climate change; dams end up losing generating capacity becaue of drought. You can see reservoirs where the level has been going down.”

One of the most drastic examples is the Guri dam in Venezuela, the source of more than 60 percent of the country’s electricity. The reservoir has lost 79% of its water level due to an extreme drought, creating a national energy crisis.

Another concern is dam vulnerability to extreme rains, which are coming more often and are more severe.

“This is a technology that hasn’t had any significant breakthroughs in decades, and it’s not the solution for climate change,” she said. “That’s just one of many things that make us think this is a technology that’s of the past.”

‘Free the Green River:’ Many alternatives to El Zapotillo Dam

The communities of Temacapulìn, Acasico and Palmarejo have for years proposed alternatives to provide the necessary water supply that do not require the flooding and disappearance of their territory.

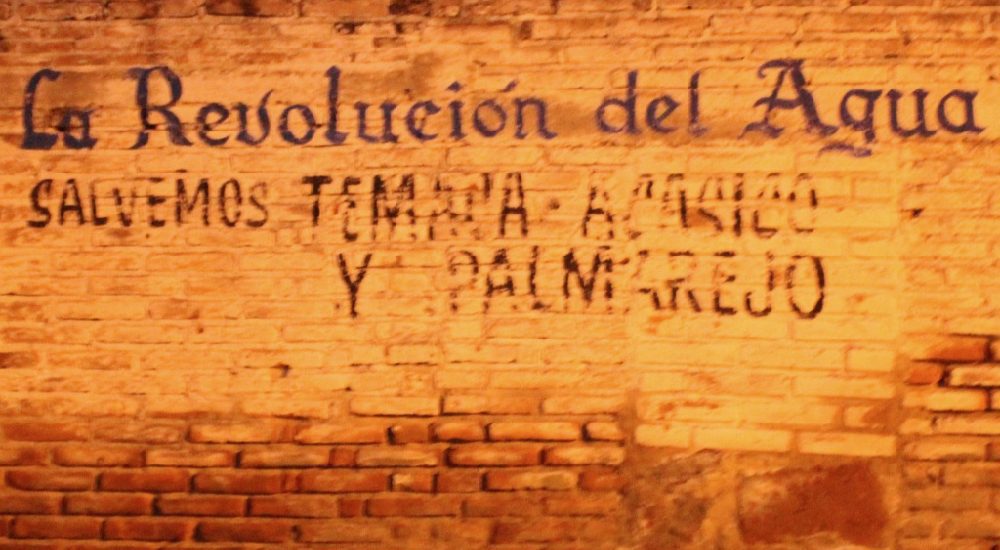

For the activist María González “the struggle of these peasant peoples in Jalisco against the El Zapotillo project is a struggle for life; their central demand is a Water Revolution, that is, moving towards a new paradigm of water management, a new model where water is considered as the sustenance of life and cultures rather than as a business opportunity; that respects and guarantees the human rights to health, food, water, life, the self-determination of peoples and the rights of nature over the rights of capital.

What Temacapulín is calling for with its “Water Revolution” is the democratization of a sector that has been rife with corruption and abuse of power since the technology began proliferating throughout the region in the 1950s. They are asking their leaders to implement an integrated water resource management policy, one that takes into account the needs of the environment and all the affected parties, not just industries and metropolitan populations. And they are calling on their compatriots to return to their roots, to come back home to their villages and revitalize the rural economy.

“The proposal is that there is water for everyone, water forever, water that respects the hydrological cycle, that respects the nature and rights of people and that these policies are constructed from below, from the communities, in the villages and in the neighborhoods.That people really have control of the resource; what has been proposed is how to move from an obsolete model to a new paradigm, where the center is in nature and involving people in the decision making… Because another kind of water management is possible,” the activist concluded hopefully.

Víctor César Villalobos Villaseñor (Guadalajara, Jalisco) has been a web editor, reporter, chronicler, photographer and literary editor. He has published two books of poetry. He loves music and movies; and, of course, Mexican mole.

- Megadam: ‘Obsolete technology’ wreaks havoc across the Americas - October 23, 2019

- A village of women in resistance - September 17, 2019

El Zapotillo IMDEC International Rivers María Gonzalez Megadams Monti Aguirre Temaca Temacapulin

Undoubtedly, the disconnection between government projects and affected populations and the lack of a holistic evaluation of the effects and consequences of this type of work is what puts the lives of many people at a crossroads. Therefore, this type of article will have a primary role in understanding the problems and the clear visualization of possible solutions. Let’s spread this information and call solidarity with these communities.