Elizabeth Vega has been incorporating art into her own work – as a journalist, a poet, a hospice and social worker and an activist – for decades. But it wasn’t until the shooting death of Mike Brown at the hands of St. Louis police officers that she began to truly understand the power of art to effect healing and change. She went on to found Arthouse St. Louis as a direct action that came out of the Ferguson Rebellion, which she describes as “a prophylaxis response to human rights issues in a community-centric space using art, poetry, music and outreach.”

I interviewed Elizabeth for a story for Yes! Magazine on craftivism and – as she prefers to call it – artivism for Yes! Magazine. As is often the case, I was only able to use a little bit of the interview in the story – but her words are too powerful to let them languish in my computer, so I share them here.

Tracy: Your idea is that everyone can do art, right?

Elizabeth: Yes. It stems from the place that art and craft is something we all have within us. It’s a way to make sense of things and a way to have cultural intersections but also process. One of the things we noticed in Ferguson is that we did a huge story wall that kept growing in size and scope. It wasn’t artistically – you probably wouldn’t see it in a gallery, because it was a lot of collages and messages. People were using materials to process something that they didn’t quite have words for yet, that would emerge as people created.

One example that I have is that we were set up right next to Mike Brown’s memorial. There was a mother and daughter who came to see the memorial. And as they walked away you could tell they were really feeling it. They were kind of walking separately. And I noticed the 13-year-old, and I said to her, “Can I give you a hug?” and this child fell into my arms and wept like it was a member of her own family – and in fact it was. We’re all part of the human family.

We were holding space with construction paper and markers and glue. And so I encouraged this mother and daughter to create something that they could put on the memorial. And they did that. They collaborated together and came up with a beautiful image, and they worked on it for about 30 minutes together. And I think that’s the role it has. Sometimes before we even have language we have images, we have things that are visual. And so holding space with art materials gives people an opportunity to process so that by end of it they do have words, and they have a greater understanding of it.

Tracy: So is that how the artivist movement began in Ferguson?

Elizabeth: It’s really interesting because that has been such a profound learning curve for us. When Ferguson first started, we didn’t even know what an art build was. Someone came and said, “Are you going to have an art build?” We had been making banners with sheets, doing things like that, but when we started to create the art build and hold space, what we were realizing was that it was a very, very important part of movement building. Because an art build allows people at all different levels of skill an entry point into social justice issues. And it’s very, very collaborative – people come with ideas and thoughts about what we’re doing, and then that space changes, the more voices you have; and then we start to riff off of each other. And then at the end you see something that has been accomplished – a beautiful banner, or a prop, or something that that, that is carried but it’s also symbolic of people’s working together.

So it very much feels that the art build does the change that we seek. It’s an opportunity to have the love of community that is creating, collaborating, and there’s a give and take. And it really is a true collaboration.

One example, we did a banner for the Stockley verdict that was going to be dropped at a baseball game. And I was like, “It would be funny if we had the cardinal bird – the Fred Bird.” And so we put him on the banner and we turned the cardinal into a protester. And based off of that, people just started adding stuff. And so he had a bat in his hand that said, “Expect Us,” the name of the group that was doing it, and was carrying a sign that said, “Racism lives here.”

And then people got together start painting and creating, which was very rewarding, at a time when so many things that not seeing – we’re not seeing success.

Tracy: That was in 2014, right?

Elizabeth: The Mike Brown verdict was in 2014, and the Stockley verdict was just last year. St. Louis and the surrounding area has been in rebellion for 4 1/2 years. We’ve been doing so many art builds – I wish you could come see it. We’ve got layers and layers of banner making. But it just really highlights all the different protests we’ve done.

I’ll tell you what’s really exciting is Christmas in Tornillo.

Tracy: Yes – so tell me about that.

Elizabeth. Christmas in Tornillo – best way to describe it is that we are taking everything the artivists have learned in Ferguson and applying it to a movement that is of national importance but maybe not in our own backyard. I mean this detention camp in Tornillo, I was there 2 1/2 weeks ago and there were 1,800 children between the ages of 13 and 17 in what amounts to a prison camp. And I was shocked because we’ve been in rebellion in Ferguson for 4 ½ years. And I was surprised at the lack of sustained resistance that has happened – or not happened.

And so Josh Rubin, who’s been there for two months, camped out in his RV, a resistance of one, watching this thing quadruple in size over two months, when it was supposed to be closed at the end of December – has been asking for a presence. And so what has come out is that Christmas in Tornillo is a creative, joyful resistance that is going to be loud enough and boisterous enough and colorful enough that the kids inside know that they’re not alone. That they know that there’s a group of people who are fighting for them. And we’ve had to be very, very strategic – because we don’t want to traumatize the kids any further. So there’s been a lot of intention built in.

So there’s going to be a lot of music. We’re going to do puppets that will pop up over the fenceline so that the kids can see them. We’re going to do a lot of singing and bell marches and things that are like – social justice carols. And it’s a 24/7 10-day occupation of the area around that detention camp.

And one of the things is two collaborative art installations that are happening. One is called Flowers for Tornillo. The idea behind it is that when you think about it there are 2,500 children behind that fence and barbed wire. And it’s really hard to mentally grasp how many is that? Just the sheer volume of the number loses humanity as a result of it. And you can’t necessarily see the kids. So what we’re doing is looking for something that can visually represent each child in that camp. And because the number is so high – we were thinking, we could use shoes. But shoes are bulky, and they’re expensive – and then what do you do with the shoes afterwards? So we were brainstorming and we came up with the idea of Mexican tissue paper flowers. And they’re bright and they’re colorful. And so we started Flowers for Tornillo. And we’re asking this country’s help in making 2,500 tissue paper flowers that are going to be hung and suspended all across that compound.

We are getting calls from Colorado, Oregon, Kentucky, Seattle, Florida – I’m answering five or six emails a day from people who are like, I’m making a flower – or Girl Scout groups, churches, mosques, people just getting together and making dinner and having parties to make tissue paper flowers.

During the 10 days of the occupation there are going to be banner drops and button making and screen printing T-shirts on site. As a community of resisters we are going to install this art installation of 2,500 tissue paper flowers, and hopefully if we have time we are going to do 2,500 luminarias – so both day and night you’ll be able to see, this is how many children we have in this camp.

I think it’s going to be beautiful. I think it’s going to pop against that desert landscape. And people are asking, how big do you want the flowers? And I’m saying, this is a collaboration. I’m leaving it very much up to the people who are creating them. It just it needs to be big and beautiful enough to capture the essence of a child. You’re making this for a particular child who is in that camp. What would you create for that one child?

People are like, what if they don’t let you put the flowers up? The hell with that. This is a protest, at a concentration camp. We will be putting up those flowers.

We’re leaving on the 23rd – it’s 18 hours, and my goal is to drive straight through We’re going to do posadas, and we’re going to have people’s assemblies.

Tracy: Going back to imagination and creativity – how has being able to tap into that been able to keep the Ferguson Rebellion alive?

Elizabeth: I think It’s been kind of amazing. As we started to make banners and do things our actions got bigger and bolder. And from that we were like, we can totally do this. The Requiem for Mike Brown, which went international, using music and song as a way of resistance – that came about because two of us had very small banners that we whipped out of our purse at the Cardinals game.

And people were so rude – we were women and grandmothers they were telling us, “Hands up, don’t move,” and other horrible, horrible racist things they were saying to us – and Sara’s a white woman and I’m brown, so it was so bizarre. And we got escorted out in handcuffs – and Sara, who was weeping because this is the first time she’s been escorted out anywhere, and the first time she’s ever been in handcuffs – she joked that, “Well, we really need a new venue.”

And from that quip in her moment of vulnerability, we began to think. And we came up with the Requiem for Mike Brown, which was a flash mob at the symphony, which went international – it went viral. When we started doing that developing more ideas – so that ended up with an action at the Muni.

Another way that has manifested is in the shields, like the shields we sent to Standing Rock. When we first started, there was a prototype that was never used – it was made of Plexiglas, which was a horrible idea – but we experimented with that, and we tried something else. And over time, the shields have really substantially evolved. We have one artist, Fabio Rodriguez, who has perfected the shield – he’s talking about doing an art exhibit, just with his shields – because they are so epic, and so beautiful.

Tracy: Of course I remember the ones you made for Standing Rock, which I delivered. Who else have you made them for?

Elizabeth: We made two for our ICE action, and he’s making some to take with us to Tornillo.

Tracy: Tell me about your ICE action.

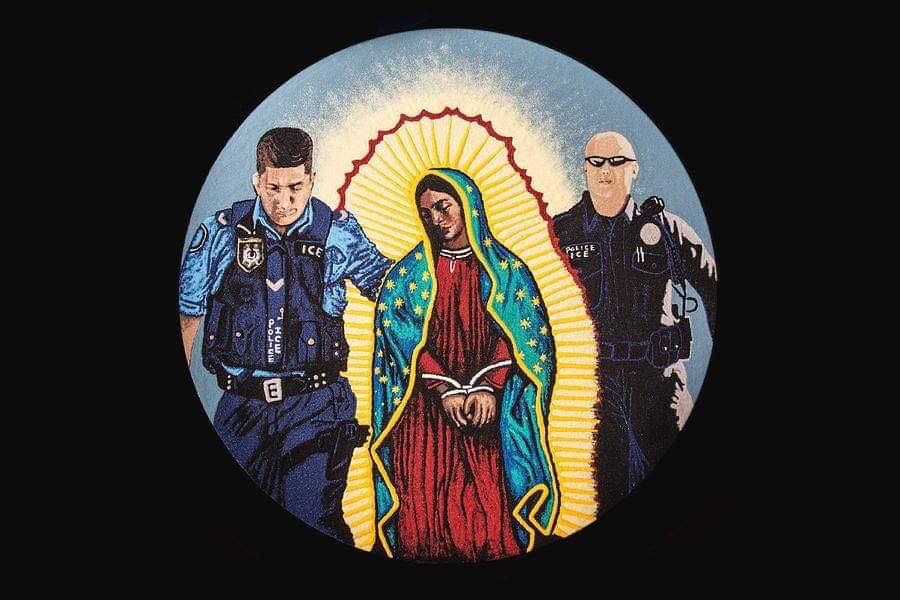

Elizabeth: Well, we did an ICE action in June. We did a diversionary march at the DOJ, and the artivists have quite a reputation. And so while we were doing the diversionary march we had 25 people, mostly clergy, filter into ICE and shut it down. And then we also set up a faux border patrol station like the kind they have in New Mexico and Texas, and we set it up in the middle of St. Louis, a block from City Hall, on the corner of Homeland Security and ICE’s building. And the banners were epic – they were beautiful banners. The one ICE confiscated said, “US-funded kidnapping” on it. I hope they hung it in their building. (laughs)

So the way that the creativity and collaboration happened is that once you realize you can do something, you just start thinking even more outside the box, and then that becomes a collective growth. If you look at our banners over the past four years, we’ve evolved as we’ve learned tricks. And that has really benefited the artists, because you’re being really prolific as you’re creating and collaborating and painting and doing all of that.

The other thing that was funny, in terms of the craftivism and the artivism. We did a whole street theater performance called “How to Get Away with Murder STL.” We planned it for two or three weeks, and it was really prop heavy. We had a lot of gear – we had a huge oversized Forward through Ferguson report that we stuffed with newspapers and ultimately set on fire in front of City Hall – and we didn’t get arrested. We laughed so hard with this action – it was so funny. We had a fake police car that we cut out of cardboard; we had killer cop clowns shooting silly string; we had people dressed up like political officials, and we had the Veiled Prophet (a traditional St. Louis icon), and every time we had a fake politician speak she’d come around with a kind of sign that translated it into people language – and we shut down City Hall.

That was last Nov. 1 or 2. I had a Día de Los Muertos party – and I was setting the match to burn the Ferguson Report. And I was like, I really don’t want to get arrested – I’m having a Dia de los Muertos party! We had barbecue pit and a fire extinguisher – but for me, that particular action – we had costumes, we had the Veiled Prophet – all of that, making the art, making the costumes, reinforced for me that at this point in the game if we’re going to do actions I want them to either make me cry or make me laugh. That’s my rubric.

The beauty of art and craftivism and this kind of resistance work is that oftentimes we are fighting against things and we’re constantly fighting against oppression, against racism, against sexism – but the art reminds us of what we’re fighting for. And that’s connection and beauty and humanity and the ability to create and dream and collaborate.

We did an occupation for the Kavanaugh nomination and occupied for five days outside outside Roy Blunt’s office. We did screen printing onsite; we were actually making shirts for the occupation onsite. And people would be like, “Oh! How much are they?” And we’d be like, “This isn’t capitalism. You can take a shirt for free; you can donate if you have it – and if you really have it, you can go out and bring more shirts, so that other people can have shirts.” That’s being the change that we seek.

One thing that we did that was so powerful – was that it became really clear that we were going to lose that battle. I was trying to think about what I could do to create a space where we could express the hurt and the pain and the frustration and the sorrow in a way that was healthy and would help us build a movement as opposed to tear it down.

And I created a “smash the patriarchy” piñata. And there I was on a Friday night and it it was 2 o’clock in the morning. And I told someone to go to the store and buy the plainest piñata you can find – because I knew I didn’t have time to build an actual piñata base. And then I reinforced it with duct tape and a couple layers and I painted headlines that were so painful and triggering and created this piñata. And the Clayton Police, who were familiar with me because of the Pumpkin Protest – they’re always monitoring me on Facebook so I don’t put things there that I don’t want them to see. And we said that we were doing this.

The cops didn’t say oh – if they do this piñata – they were trying to figure out what the piñata was going to be, they were making bets on what the piñata was going to be and how we were going to hang it. So right after the Kavanaugh confirmation we went out to the streets to protest – and in this very, very raw moment – because the cops were kind of circling around us, the confiscated the bat – so I grabbed a tent pole and had two guys hold the piñata in the middle of street, with a big rope on either end. And I handed the pole to Cory Bush, who is very publicly a survivor of assault, who helped organize the protest, who had so much of a heart in it – and I said, “Cory, hit the piñata.” And she hit it once, and I said, “No, hit it until you don’t feel like hitting it anymore.” And she started to hit that thing, and by the second or third whack, she was hitting it so hard she had tears streaming down her face. And by the end of her hitting it until she was spent and exhausted, everyone around her on that street had tears streaming down their faces as well. It was such a raw human moment.

And to me, that’s the power of artivism. That is the heart and soul of resistance — it reminds us what we fighting for, not just what we are fighting against.

Those are the lessons that we learned in these 4 ½ years, and the lessons we hope to take to Tornillo so that others who are activists and artists and musicians can see that there are ways to do organizing that are way more effective than just simply marching in the marching in the streets.

To me, music and art should be the heartbeat of any movement.

Tracy: Is there anything else you’d like to say before I let you go?

Elizabeth: I want to call on all people who are reading this article to tell you that we are long overdue in rising up in this country. Long overdue. We’re to the point where we have literally a prison camp of teenagers in the middle of the desert. And that didn’t happen by accident. That didn’t happen just because Trump got in. That happened because in this country, for a while now, we’ve been turning a blind eye to the accumulation of crimes against humanity and injustice. And it’s that time where you can’t be a fence sitter anymore. If you are silent, you are complicit. And whatever tools, resources, skills that you have – it is time to find your way and increase your work to fight against this.

I don’t think that I’m going to see in my lifetime the changes I wish would come. But I’m doing this now for my children and my grandchildren because I cannot in good conscience leave them a world like this. I just can’t.

Don’t just read about all of this great craftivism and artivism. Figure out a way how you can do it, and make it effective, using the skills that you have.

- A Year of Listening, Resistance, and Hope: Reflections from The Esperanza Project - December 30, 2025

- Arts to Breathe: A Continental Act of Dignity - November 28, 2025

- “It’s not grass, it’s a milpa”: Defending Life on Avenida Federalismo - October 8, 2025

artivism Black Lives Matter child detention Christmas in Tornillo Elizabeth Vega Ferguson St. Louis Tornillo Detention Center