“Frog juice” is thought to be an aphrodisiac in Peruvian culture, as well as a medicine capable of curing many ills, so traditionally locals blend parts of the body of the amphibians with fruit and other herbs as a type of tonic. Unfortunately only the giant Titicaca frog will do, and this tradition is leading to the extinction of one of the world’s largest frog species.

A team of Peruvian scientists has intervened in an effort to save these frogs from imminent extinction due to pollution and human consumption. The frog, whose scientific name is Telmatobius culeus, is ironically nicknamed the “scrotum frog” due to the appearance of its soft, flaccid sack-shaped skin and the folds it creates on its bulky body. These folds allow it to increase the absorption of oxygen through the skin and spend most of its time underwater. They are among the largest aquatic frogs in the world, reaching up to 8 inches from head to rump, and there are records of specimens up to 20 inches.

Sadly, however, scientists are seeing a precipitous decline in the frog’s populations, in part due to hunting.

Para leer este artículo en Español haz click AQUÍ

Titicaca is the world’s highest navigable lake and is the only source of fresh water in the entire Altiplano of the Central Andes, a vast expanse of high desert that includes Peru, Chile and Bolivia.

Both the giant frog and the Titicaca grebe are considered “indicator species,” meaning they help authorities measure the health of the ecosystem and other species around them. Scrotum frogs are also a keystone species within the ecosystem of this 8,300 square kilometer lake. They help maintain the balance in the food chain, raising the levels of nutrients in the water, keeping the population of snails and shrimp under control and serving as food for some fish and various birds such as seagulls and herons. The extinction of this species would trigger an ecological catastrophe in the most important source of water for Peru and Bolivia.

That is why scientists are extremely alarmed at the dramatic decline in their population in recent years. In the decade between 1994 and 2004 alone, there was an 80 percent decline, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); and the situation has only gotten worse; a recent study put the decline at 90 percent, with an estimated 30,000 remaining frogs fighting for their lives.

In 2016, more than 10,000 dead frogs were found in the Peruvian part of the lake. Authorities noticed sludge and solid waste during an investigation, and local media reported that sewage runoff may have played a role in the deaths, according to a report by CNN.

Biologist Dennis Huisa-Balcon, a researcher for four years on the situation of the giant frog, shared with The Esperanza Project that despite the difficulty of achieving an accurate count of the population due to the immensity of Lake Titicaca, scientists are clear that the decline has been precipitous.

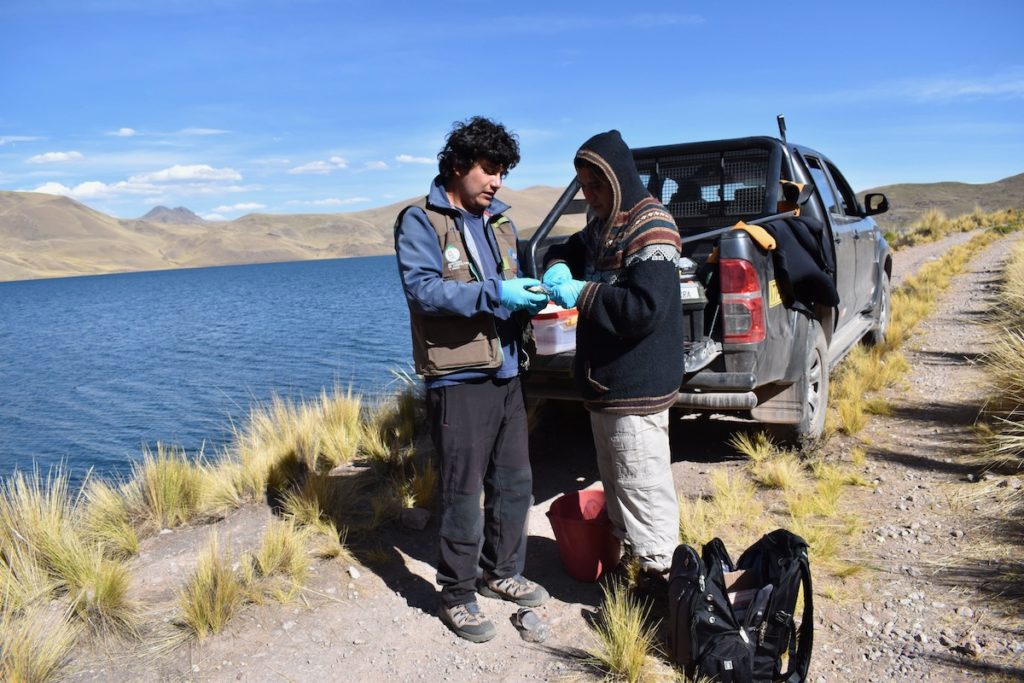

Specialists from Peru and Bolivia who operate through the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation have developed a binational plan with SERFOR, the Peruvian National Forest and Wildlife Service, as well as civil associations such as Procarnívoros, to study the causes and solutions to this problem.

Clandestine mining, the introduction of trout for fishing in certain areas of the lake and contamination by industrial and household sewage, in addition to hunting, are the main culprits for the disappearance of this important species.

That is why legislation and education are key factors in protecting these frogs. The conservation project that is being carried out includes workshops and talks on environmental education with teachers and students from schools in the villages where the scrotum frogs are hunted and where they are sold, providing training for local authorities on the importance of this species. Team members are sharing the alarming results of their research with people in local markets, so that they become aware that the extraction and sale of the Titicaca giant frog are illegal activities.

“We have identified around four extraction zones for the giant frog in Lake Titicaca, as well as the cities where they are sold: Juliaca, Puno, Desaguadero and Ilave,” said Dennis Huisa. “What is important about this? It is that these four cities are just where the road connects Puno with Bolivia. And Puno, since it is in the south, connects with the rest of the territory. These towns are strategic places, and there is evidence that they take the frogs to other places.”

The team has scored some major successes, with interventions of illegal frog traffickers in which they have recovered up to 2,000 frogs that were transported in wooden boxes for sale.

“We are giving interviews on the radio and on television to demystify the idea that the frog has medicinal properties and to make known the importance of this species so that people no longer buy or trade it,” Huisa said.

“In the community of Lagunillas we have confirmed the existence of a new population of frogs, 80 kilometers from Lake Titicaca,” Huisa explains. “This is good news because it is a remote lake that does not face the threats of Lake Titicaca. However, fish farming activity is booming in Laguna de Lagunillas and this could become a threat,” since these introduced species of fish alter the frogs’ habitat and are predators for their tadpoles.

A survey was carried out in the community of Lagunillas, where the new population of giant frog was found, and it was discovered that the inhabitants do not consume it there, which gives hope that it can reproduce.

Unfortunately, in the communities of Lake Titicaca, the frog is consumed a lot, mainly for its alleged healing properties. They do not cook their meat, but rather skin the frog and blend it together with other ingredients to make tonics, which are sold in plazas and markets. However, studies have shown that they are not high in protein, and these tonics have not actually been shown to be much more nutritious or beneficial than they would be with the other ingredients, without the frog.

The outreach project, dubbed “Wanquele,” is currently underway. “We gave it this name because it is the name of the frog in Quechua. With this project we are trying to unite the conservation efforts of the NGOs with the work of the state. I have seen that between these two they can synergize and make better efforts for conservation,” maintains Huisa-Balcon.

According to an informative SERFOR brochure, “In Peru, the giant frog is categorized as Critically Endangered according to Supreme Decree No. 004-2014-MINAGRI, which updates the list of wildlife species threatened with extinction. Therefore, its capture, possession, trade, transport or export for commercial or other purposes is prohibited. Internationally, it is included in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).”

The other threat to the frogs — the pollution that is being discharged into the lake from a wide range of sources — is a much more difficult problem to solve, Dr. Huisa-Balcon explains. “It is difficult to regulate in Lake Titicaca the emissions of sewage produced by the riverside cities, as well as the emissions caused by mining. These contexts also have regulatory frameworks, but illegality prevails. Despite being one of the countries with the largest amounts of specialized legislation, its applicability and control are an irony.”

It is hoped that through the legislation, the operations to confiscate the poached frogs, and above all through the information and education of the inhabitants of the surroundings of Lake Titicaca, it will be possible to raise awareness about the importance of this amphibian and stop the illegal hunting.

“Currently many social organizations are getting involved in conservation activities,” said Huisa-Balcon. “We seek to identify these organizations and add them to this common effort, which is to protect this species that may not be charismatic, but there is a cultural aura around it and it represents healthy habitats.”

The collective will continue to work toward developing new conservation strategies around this aquatic frog that involve the habitat and sustainable development of this unique water resource, which is an essential reserves for this highland region, where the Andean altitude and desert conditions make this place one of the most vulnerable to climate change scenarios.

“We hope that people can contact us and join the conservation of this unique species,” concluded Huisa-Balcon. “We’d like to share the findings that we are learning along the way, and we would like to hear the ideas of others to make an effective conservation plan that involves many actors.”

Dr. Huisa-Balcon and SERFOR would like to thank the Friend of the Earth organization for the support they have given them in their campaign to conserve the scrotum frog.

- Tonalá awakens: Spirituality Expo revives the sacred legacy - December 11, 2025

- Last Chance to Save Mexico City’s Water Forest - June 1, 2024

- March 8: ‘Identity can never be silenced.’ Misak women fight back in Colombia - March 8, 2024

Friends of the Earth scrotum frog Titicaca giant frog Titicaca Lake UICN