On Christmas Eve, 2018, in a remote corner of the Texan desert, Esperanza Project editor Tracy Barnett interviewed activists organizing a creative resistance against the detainment of thousands of youths at the now defunct Tornillo Child Detention Center. It was deep in winter and the wind bit at the chain-link fence as she spoke with El Paso native and “artivist” Juan Ortiz, as he put the last decorative touches on a Christmas tree constructed with plastic, barbed wire, and ornaments made with tear gas canisters. At the top of the tree, like an angel of nativity, was the image of 7-year-old Jackelin Caal Maquin, an indigenous Guatemalan child of Qʼeqchiʼ Maya descent, who died in the custody of Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The cause of death was listed as septic shock, fever and dehydration.

As he decorated the tree with plastic water jugs left for refugees moving northwards across the desert, Juan told Tracy: “I wanted to highlight the way water has been weaponized and used as a tool of oppression.” The pair were unaware another indigenous child in the custody of Customs and Border Protection would not live to see Christmas Day. Eight-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo of the Chuj Maya people from northeastern Guatemala would be pronounced dead at 11:48 p.m that very Christmas Eve. And Felipe wouldn’t be the last child. On the other side of the chain-link fence, the heavily guarded tent city of Tornillo housed over 2,300 migrant children at the height of its operations. And this camp was one of many.

At least 5,400 Central American children were forcibly separated from their parents to appease a vainglorious president and his xenophobic base. Their suffering was needless. Physical and sexual abuse of migrant children inside the government-funded detention facilities was rife. Meanwhile, detention camps ran a profit for shareholders and private contractors. The migration crisis became a multi-million dollar bonanza for a for-profit prison system operating on an industrial scale. Neglect was great for the bottom line. Under President Trump’s “zero tolerance” border policies, the letter and spirit of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was violated on American soil more than at any other point in modern history.

The Tornillo Child Detention Centre was eventually closed, the children it housed were scattered across other detention centers in different parts of the country. One day the stories of these children will be told with their own words through their own eyes. Today we can tell the stories of the men and women who fought for them on the other side of the chain-link fence. This longform article will take you from the march on Tornillo Child Detention Center and the height of President Trump’s child separation policy, to President Biden’s decision to reopen a Trump-era detention centre in Carrizo Springs, Texas, to hold 700 teenagers at the end of February.

ARTICLE 6 ON THE CHILD’S RIGHT TO LIFE

A summary of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child helps us adults understand and digest the 43 Articles in the human rights treaty in easy-to-read English without having to know the intricacies and nuances of international humanitarian law. Article 6 of the summary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Every child has the right to life. Governments must do all they can to ensure that children survive and develop to their full potential.”

UNICEF’s “child-friendly” summary of the international human rights convention speaks directly to the child: “You have the right to be alive.”

But something happened that Christmas inside the sprawling and overcrowded immigration detention centers that led to the deaths of Jackelin and Felipe. And these were not isolated incidents: three other children would die in the coming months. Article 6 on the child’s right to life had been violated. The consequences were catastrophic.

“The purpose of CBP isn’t long-term detention,” Allegra Love, an immigration lawyer and former head of the Santa Fe Dreamers Project, wrote in The Esperanza Project. “In fact, with children, there are rules about how fast they have to be transferred. In the case of the last boy who died, the law required that he be transferred in 72 hours.”

Allegra goes on to detail the death of child after child—five Central American children in five months, inside CPB custody…

– Dec. 8, 2019. Jakelin Caal Maquin, age 8, dies of an infection after being in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody in New Mexico and Texas.

– 16 days later on Dec. 24, 2018, Felipe Gomez Alonzo, age 8, dies of the flu and infection in CBP custody in New Mexico.

-April 30, 11 days after he was apprehended by CBP, Juan de León Gutiérrez, age 16, died of an infection after being transferred to Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) custody in Texas.

-May 14, an unnamed 2-year-old died in the hospital after being in CBP custody in Texas. [Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, the fourth Guatemalan child to die in as many months]

-Six days later, on May 20, Carlos Hernandez Vasquez, age 16, died in CBP custody in Texas after having flu-like symptoms.

What is going on?

Allegra Love, Santa Fe Dreamers Project

These migrants, as I have mentioned every single time I write or utter a word about them, are not breaking the law. They are lawfully seeking protection from violence. Yet rather than protection, they are met with brutal policies designed to make the journey as difficult as possible. Protection would be apprehending someone and doing a full medical screening and holding them just as long as needed to ascertain their identity and their intention to seek protection in the US. It would mean making sure that while they are in the custody of the US government they have food, water, proper medical care, and a proper place to bathe and sleep. Instead, these people are put in the “hieleras.” If you don’t know what that is, do a Google image search with the terms “hielera CBP” (if you just put “hielera” you will get pictures of coolers).

— Allegra Love

Mother Jones summarized the conditions for Central American children detained in the American borderlands like this: “Migrants—especially unaccompanied kids—allege suffering a lot of harm at the hands of CBP agents: sexual assault, beatings, a lack of basic toiletries. But few forms of abuse are more pervasive than the hielera—the Spanish word for “icebox” that detainees and guards alike use to describe CBP’s frigid holding cells.”

Furthermore: Article 27 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Every child has the right to a standard of living that is good enough to meet their physical and social needs and support their development. Governments must help families who cannot afford to provide this.” The child-friendly text tells children: “You have the right to food, clothing, a safe place to live and to have your basic needs met. You should not be disadvantaged so that you can’t do many of the things other kids can do.”

ARTICLE 24 ON THE CHILD’S RIGHT TO HEALTH

Article 24 of the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Every child has the right to the best possible health. Governments must provide good quality health care, clean water, nutritious food, and a clean environment and education on health and well-being so that children can stay healthy. Richer countries must help poorer countries achieve this.”

UNICEF’s child-friendly summary of Article 24 speaks to kids: “You have the right to the best health care possible, safe water to drink, nutritious food, a clean and safe environment, and information to help you stay well.”

When a child gets sick, there is a moral and legal obligation for governments to attend to that child’s health. Putting vulnerable migrant children in hieleras or iceboxes is not conducive to Article 24 by any stretch of the imagination. That’s because these policies were designed to be a deterrent, punitive in nature, and not in the interests of children, their health, safety, or development. Ana Tiffany Deveze, a teacher, community organizer, and mother of two, wrote her powerful testimony for The Esperanza Project to illuminate the conditions inside immigration detention on the American borderlands:

“On Dec. 8, 7-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquín died in El Paso while in Border Patrol custody. Then, on Christmas Eve, Felipe Gómez Alonzo, 8 years old, died in El Paso while in Border Patrol custody. That night we heard reports of hundreds of migrants dumped by officials at the Greyhound station in El Paso’s historic Duranguito neighborhood…”

…

They were covered in dust, bird poop, and their hair was matted and speckled with rubble. They couldn’t form a line, they only sat at the tables and stared, shellshocked, as volunteers mobilized into a type of triage mode. One woman told Claudia that her child was sick while they were under the bridge and she asked for medical assistance but wasn’t seen until her child was projectile vomiting incessantly. A lot of the children were vomiting that night. She told me there were points where she thought the children weren’t eating because they were in shock, but then they would run to the toilet and she realized they couldn’t eat because they were so sick.

…

Consider this, along with the fact that in the weeks following my arrest, reports emerged of vigilante militia members detaining migrant families, including children, at gunpoint at their camp in Sunland Park. They were said to have been camped out at the site for months, detaining people at gunpoint, and posting videos of migrant families on their knees while Border Patrol agents stood aside. The police were reported to have visited the site and asked the militia, who called themselves the United Constitutional Patriots, to leave the site by the week’s end, meaning that they had several days to stop trespassing. The group was evicted the following day and are said to have planned to relocate and continue operations, however.

— Ana Tiffany Deveze

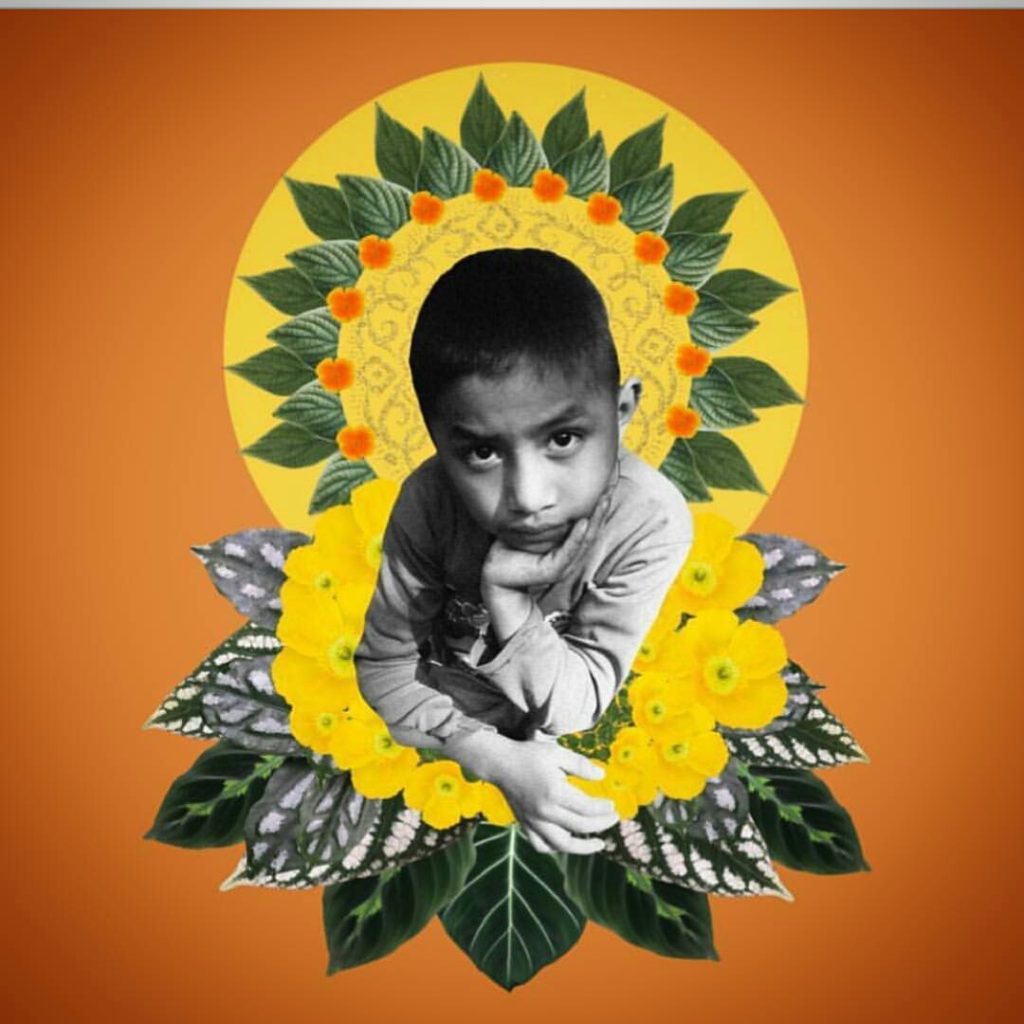

Ana Tiffany Deveze remembers being given a card with the now iconic image of Jakelin Caal, the 7-year-old Qʼeqchiʼ Maya girl surrounded by foliage, rose petals, and a solar halo. “It was to remind me of why we do what we do, and I thought about the way she died, sick in Customs and Border Patrol custody. These are the conditions that children are being subjected to in the United States, while they get sick and we lose them.”

ARTICLE 22 ON A CHILD SEEKING REFUGE

Article 22 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “If a child is seeking refuge or has refugee status, governments must provide them with appropriate protection and assistance to help them enjoy all the rights in the Convention. Governments must help refugee children who are separated from their parents to be reunited with them.” The child-friendly text speaks to the heart of it: “You have the right to special protection and help if you are a refugee (if you have been forced to leave your home and live in another country), as well as all the rights in this Convention.”

Jakelin Caal’s now iconic image became a symbol for those who believed that what was happening was wrong. Wrong in the letter and the spirit of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Wrong in every sense of the word. Her image is distributed at peaceful protests, carried around in wallets and purses, and appeared on Juan Ortiz’ Christmas tree beside a chain-link fence. For Gaby Zavala, however, it was the image of a 15-year old Honduran girl broadcast on TV as she sat in her obstetrician’s waiting room in the Texan city of Brownsville that burned into her memory and galvanized her to action.

Across the river in Matamoros, Mexico, the news showed the Honduran teenager swept away by the current as she bathed in the Río Grande. An asylum-seeker filmed the September incident as two others pulled her from the water, trying—and failing—to resuscitate her. Gaby was moved to action in her obstetrician’s waiting room. Inside of two days, she had organized a team of volunteers that raised enough money to set up basic bucket-bathing shelters and bring in a truck of water so that migrants could safely bathe. Within a month, she had put down a deposit on a house across the street from the encampment and opened the Resource Center for Asylum Seekers. Gaby, who was born in Brownsville and grew up on both sides of the river, remembers the moment. “That’s when we said, ‘No más —This can’t happen again.’”

‘It’s easier to control people after they are emotionally and mentally broken down — and that is exactly what is happening inside of these detention centers.’

— Gaby Zavala, migrant defender from Brownsville

Gaby Zavala holds a list in her hand as she makes her way through a maze of nearly 100 tents in a plaza in Matamoros, Mexico, looking for asylum seekers to assist that day. Her organization of volunteers, the Asylum Seeker Network of Support, had already identified a number of migrants who needed help with specific tasks such as case management, help finding temporary shelter, and navigating the dangers of living on the streets of Matamoros. Like most of the families she assists that day, a 23-year-old man from Honduras and his toddler have been living in the plaza next to the Brownsville & Matamoros International Bridge. The site is just an hour from the place where they were kidnapped en route to the US and held for ransom.

– Garet Bleir

ARTICLE 33 ON PROTECTION FROM THE DRUG TRADE

Article 33 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Governments must protect children from the illegal use of drugs and from being involved in the production or distribution of drugs.” The child-friendly version for Article 33 tells children: “You have the right to protection from harmful drugs and from the drug trade.”

It’s New Year’s, 2020, a little over a year ago now, and a year after the image of a little Guatemalan girl—like the star of Bethlehem—blessed a Christmas tree beside a chain-link fence to illuminate the way towards a more moral universe. The Tornillo Child Detention Centre is now closed. Thousands more children are still held in an extralegal greyzone in detention camps across the American borderlands. In a number of weeks, the coronavirus would wreak havoc across the country and terrorize the children crammed into caged holding cells and hielera iceboxes across the detention camps in the American borderlands.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, developed in conjunction with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, has forced migrants fleeing cartel violence into camps on the riverbanks of the Río Grande. In the weeks over New Year’s 2020, Tracy Barnett interviewed the migrant families in Matamoros, Mexico:

On the Mexican side of the Río Grande there are no heavily guarded detention camps, military-grade canvas tents or hieleras. On the other side of the border thousands of children aren’t huddled in cages, cocooned in aluminum foil blankets for warmth, like in sprawling detention camps across Texas or New Mexico or Arizona. But the drug wars still rage. Cartels still recruit young boys as foot soldiers for their wars of attrition. Human traffickers still prey on young girls for prostitution like coyotes. Missing persons posters dominate community noticeboards in the makeshift camps that populate the riverbanks of the Río Grande. And American made military grade weapons are still smuggled across the border at an industrial scale to empower organized crime as they cash in on the United States’ insatiable demand for opiates and cocaine.

There is no simple answer to the drug wars and the refugees they cause but there is an obligation to help. Or at the very least do less harm. The United States both fuels and funds the drug wars across Latin America: its high-caliber assault rifles and other weapons of war that are smuggled southward over porous borders combined with the American market’s insatiable demand for billions of dollars of narcotics have both profoundly altered the landscape. Hundreds of thousands are dead and many thousands more are missing and the caravans of refugees fleeing poverty and cartel violence continue to move northwards towards the American borderlands and asylum.

Sarah Towle, the award winning author and contributor for The Esperanza Project, investigates the origins of the migration crisis from its roots in Central American civil wars to Los Angeles prisons in her profile on the pioneering human rights activist Jennifer Harbury:

The gang came for “Sam” on his 15th birthday. He’d said “no” to them before. This time, they gave him an ultimatum: Join us or die. But poor though his family was, Sam did not want to enter a world of crime and brutality from which there was no escape.

The gang, born in Los Angeles and known throughout the Americas as Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13, doesn’t give third chances. The next time they came for Sam it was to run him over with a car.

They left him for dead. Remarkably, Sam pulled through. When he awoke three days later, with a head injury and badly bruised body, his mother pressed a wad of cash into his hand — about $30, maybe a little more. It was all she had in the world, plus what she was able to beg off friends. Like so many other Northern Triangle mothers, she faced a Sophie’s choice: unable to protect her boy from the cartel gangs, she had to kick him out of the nest. It was the only way to save his life…maybe. Along with the money, and through a veil of tears, she gave Sam one simple word of parental advice: “Run!”

Sam ran toward El Norte. He traveled on foot and by bus from Honduras through Guatemala, then rode the back of La Bestia, the perilous freight train, through Mexico to Texas. En route, he saw fellow migrants miss their step and get sucked between train and rails, their bodies shredded. He learned quickly how to identify and to steer clear of the gang members who preyed upon the migrants as they made their way north. He met teenaged girls, full with the children of their cartel rapists. He met other boys whose loved ones had been exterminated when they, like him, turned down MS-13 or Barrio 18 or Los Zetas. He met families of means back home who, robbed of every penny they’d painstakingly saved to pay a coyote to get them safely to The Promised Land, were reduced to riding the dangerous rails with him.

Young Sam ran toward the promise of a better life. He made it to the US border at Texas, where he tried to swim across the Río Grande and nearly drowned. He was plucked from the swirling waters by members of one gang or another, but he managed to get away.

At Reynosa, Mexico, a recognized US port of entry, Sam walked across the bridge to the Customs Border & Protections (CBP) office at the northern end. There, he requested asylum. He was labeled a “UAC” — government-speak for an unaccompanied minor — and passed into the bureaucratic tangle that is the Office of Refugee Resettlement. ORR kept him in custody, locked up in a “shelter” — government-speak for an unregulated, off-limits detention center for kids — until his 18th birthday, when they could not legally hold him any longer. There, he received little education and was sexually abused by staff at the shelter in which he was incarcerated, as were a number of other kids.

Sarah Towle – The Esperanza Project

ARTICLES 5, 9, & 10 ON CHILD SEPARATION AND FAMILY REUNIFICATION

Article 9 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Children must not be separated from their parents against their will unless it is in their best interests.” The child-friendly text for Article 9 says: “You have the right to live with your parent(s), unless it is bad for you. You have the right to live with a family who cares for you.”

Article after article of the convention to protect children was wilfully and negligently violated during the Trump administration, but it was the violation of Article 9 that drew international condemnation and outcry from every corner of the planet.

Sarah Towle’s analysis of the testimonies contained in legal filings illuminates the trail of destruction wrought by the policy of child separation.

“Now Federal Judge Dana Sabraw, ruling in favor of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in the matter of Ms. L. v. US ICE, ordered that all separated families be reunified by the end of July 2018. However, though the cruel policy had been in practice for months before it was publicly rolled out in the Río Grande Valley (RGV) that spring, there had never been a system for keeping track of who was taken from whom. ICE didn’t have the data to comply with Judge Sabraw’s order.”

…

“An immigration attorney, Jodi knew the only way to reunite separated families was to spring the parents from ICE prisons first, while simultaneously tracking down the kids, so reunifications could happen as quickly as possible. ICE was desperate for help.” writes Sarah Towle. “The officer asked if I’d be willing to share my list that located lost parents and children.”

Sarah Towle

Family members had in many cases been incarcerated miles apart. Parents had been fast-tracked for deportation, turning babies and toddlers, too young to provide a parent’s name or country of origin, into orphans and wards of the US government. The government didn’t have a tracking system and migrant children disappeared into the for-profit prisons and risked being lost from their loved ones forever. Children are still missing. The state’s failure on every conceivable level was catastrophic.

At the McAllen Courthouse the following Monday, Jodi saw it with her own eyes: “Moms, dads, they were distraught, beside themselves. They couldn’t attend to the proceedings or respond effectively to the judges’ questions. They just wanted to know what happened to their kids.”

According to a second Federal class-action lawsuit, Dora v. Sessions, “Every single parent described the moment that their children were taken from them as the single most vividly horrifying experience of their lives: ‘shattering,’ ‘unbearable,’ ‘a nightmare,’” (p. 12, para 46). Having fled their home countries, in large part to protect their children, they were emotionally and psychologically traumatized at losing them, most cruelly, to men in uniform.

“Dora” fled with her seven-year-old son after years of extraordinary abuse at the hands of her husband. She arrived at the border and turned herself in to immigration agents, requesting asylum. When a CBP official took her boy, she begged and pleaded, explaining that after all he’d been through, he needed her. The officer told her “she deserved to lose her child and would not see him again until he was 18 years old” (p. 13).

“Alma” was taken to court the day after requesting asylum for her and her two children, aged seven and nine. When she returned to the CBP processing center, her kids were gone. She, too, was told she would never see them again: “that they would remain in the US and she would be deported” (p. 14).

Likewise, “Esperanza,” whose husband “gifted” her to a MS-13 gang leader as a sex slave, ran to save her son, who witnessed her being raped too many times to count. A CBP officer told her, “he belongs to the US government now” (p. 17).

Herself a mother of three, as well as a fluent Spanish speaker, Jodi understood their stories — and their pain — on a deep level. She obtained the “Alien” Identification numbers (A#s) of seven women in court that first day. She followed them to PIDC where they’d been sent. She told them, “I’m going to get your children back.”

She hoped she could.

— Sarah Towle

Article 5 on UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states: “Governments must respect the rights and responsibilities of parents and carers to provide guidance and direction to their child as they grow up, so that they fully enjoy their rights.” Furthermore, Article 10 on Family Reunification states: “Governments must respond quickly and sympathetically if a child or their parents apply to live together in the same country. If a child’s parents live apart in different countries, the child has the right to visit and keep in contact with both of them.“

ARTICLES 3 AND 4 ON THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE CHILD AND THE LAWS TO PROTECT CHILDREN

Article 3 of the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child states: “the best interests of the child must be a top priority in all decisions and actions that affect children.” Article 4 of the convention states that “Governments must do all they can to make sure every child can enjoy their rights by creating systems and passing laws that promote and protect children’s rights.“

The New York Times reported that: ‘This transformation of the American immigration system has been perhaps the [Trump] administration’s boldest accomplishment, overseen with single-minded focus by Stephen Miller, a top adviser to President Trump with an affinity for white nationalism. Jeff Sessions, the attorney-general in the spring of 2018 when child separation came into force, is on the record saying, “We need to take away children.”‘

Age made no difference. Even nursing mothers were cleaved from their babies to satisfy an affinity for white nationalism over the best interests of the child. Jennifer Senior in the New York Times called out a rap sheet of Trump lackeys—Rod Rosenstein, Jeff Sessions, and Stephen Miller—who were the architects of child separation with these words: “Let’s start by calling this policy what it really was: A state-directed effort to intern immigrant children, some exceptionally young — so young that they were still breastfeeding, so young that they were preverbal, so young that they were not yet aware of their parents’ names. To wrench these children from their mothers and fathers and detain them for months on end required a bureaucracy, with cruel architects at the top — specifically, the former attorney general, Jeff Sessions, and Stephen Miller, Trump’s senior policy adviser — and a dedicated pyramid of helpers directly below.”

The systems and laws to protect children failed. The best interests of the child were not a priority for decision-makers. A toxic cocktail of institutional neglect, bureaucratic ineptitude, and racist malice trickling down from the very top of the Trump pyramid scheme of governance made this possible. There’s no doubt child separation was the touchstone of Trump’s malignant immigration policy, but the culture of child abuse and impunity inside CBP and ICE has been documented for years. Garet Bleir, for Intercontinental Cry and the Esperanza Project, explored the history:

But the abuse did not start with President Trump. There has long been a culture of abuse within CBP and ICE as noted through newly released documents. In mid-October, the ACLU Foundation of San Diego and Imperial Counties published approximately 35,000 pages of heavily redacted material from DHS, ICE, and CBP after a lengthy legal battle. The documents outline abuse and neglect of unaccompanied immigrant children in US CBP and ICE custody between 2009 to 2014 including denial of medical care, verbal threats, physical and sexual abuse, and inhumane detention conditions.

Within these documents, children described being run over with vehicles, stomped on and kicked, tased, and punched as well as a wide range of verbal abuse. One complaint against ICE detailed an agent that told child detainees he was transporting to “’shut the f*** up’ and threatened that ‘if I hear any s*** in the van I’m going to smash your f***ing faces in,’” the documents read.

Throughout the complaints, children noted being deprived both of drinkable water as well as edible food and held in unsanitary and freezing cells with “inadequate bedding and no access to personal hygiene items.” Children also reported being threatened with death and rape, told to remove their clothes before being questioned, and CBP officials inappropriately touching them. After Trump’s inauguration it is clear that these abusive conditions did not improve but in many cases continued and intensified.

– Garet Bleir Facebook: GaretBleirJournalism IG: @GaretBleir

RATIFICATION OF THE UN CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD

The United States has signed the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It even honorably contributed in the drafting of the convention, but it is still the only member state of the United Nations that is not a party to the convention. If a Joe Biden presidency hopes to fulfil its election pledge to restore the soul of America where the best interests of the child are sacred, then it must first ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Joe Biden has generated considerable goodwill at this early stage of his presidency for rolling back the most racist and punitive policies of his predecessor that targeted migrant children. In recent weeks the Migrant Protection Protocols or “Remain in Mexico” policy was reversed, allowing thousands of asylum seekers stranded in border cartel zones to finally reunite with their waiting families in the US. The infamous Matamoros encampment, home to thousands of marooned families, was closed. However, the root problems have not been resolved, and a legal limbo awaits asylum seekers arriving at the border every day, including thousandds of unaccompanied minors. And immigrant advocates insist that the same level of scrutiny should be applied to Biden’s policies as that of his predecessor.

As of March 8, 2021, the number of unaccompanied migrant children arriving at the US border has tripled in two weeks to 3,250. The New York Times reported that more than 1,360 unaccompanied children have been detained in CBP beyond the 72 hours that the law permits before the child must be transferred to a shelter. According to the New York Times, until last Friday the shelters managed by Health and Human Services were at reduced capacity because of the pandemic. Now as another surge of migrant children reaches the border, these restrictions have been lifted and the CBP holding cells are close to “maximum capacity”.

There is no easy answer to the migration crisis. And there is no airbrushing the fact that these facilities are the same detention centers that attracted global condemnation and were often referred to as child cages or concentration camps. Biden should be applauded for creating a taskforce to reunite migrant children that were forcibly separated from their parents under Trump’s policy of zero tolerance. The reports that a new camp, originally created for oil field workers in Carrizo Springs, Texas, is to be reconverted to hold 700 teenagers, are troubling. The Convention of the Rights of the Child can act as a North Star, guiding policymakers, with deference to Article 3 of the Conventions: “The best interests of the child must be a top priority in all decisions and actions that affect children.”

Until then, The Esperanza Project will continue covering stories from the frontline of the migration crisis across the American borderlands and beyond. And we will leave you with one more story about hope that touches on Article 28 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child which states: “Every child has the right to an education. Primary education must be free and different forms of secondary education must be available to every child. Discipline in schools must respect children’s dignity and their rights. Richer countries must help poorer countries achieve this.”

On a trip to the Matamoros refugee camp on Mexico’s northern border, Tracy Barnett met Nathan Boddy and his wife, Dr. Johanna Dreiling, who were among the surge of grassroots volunteers responding to the migration crisis. Dr. Johanna worked at the camp clinic alongside volunteers, and Nathan chronicled his wife’s work, as well as his efforts to educate migrant children who had made the perilous journey of over a thousand kilometers.

“Twice I brought my two young boys to work with me in Mexico. I felt it important that they be there to see this point in our nation’s history, even if it’s not occurring on our soil. I was glad to see them play with other children in the camp and I fully realize that their impact in the migrant camp might be greater than my own.

During one sunny afternoon I set a table with pencils, crayon and a stack of blank paper. I gave my boys some math problems to tackle and before long there were at least eight children at the table doing the same. I’ll admit that teaching multiplication and division in Spanish might have been more confusing to the children than it was a help, so I was relieved when several kids asked if they could just color instead. Half an hour later one young girl from El Salvador who’d been particularly bright with her math problems, approached me with a sheet of paper. Upon it she’d colored a scene that was easily distinguishable as a grass-lined beach and blue ocean water filled with sea creatures. What struck me most were the structures at the center of the picture: a swing set and monkey bars. She thanked me for teaching her, gave me the picture and disappeared with the others.”

Nathan Boddy – The Esperanza Project