On the morning of April 15, Elizabeth Vega and Ana Tiffany Deveze walked into to the El Paso Police Department and turned themselves in. Their crime: a peaceful protest against the U.S. Border Patrol, for which they and 14 others are being charged with offenses ranging from misdemeanor trespassing to felony criminal mischief.

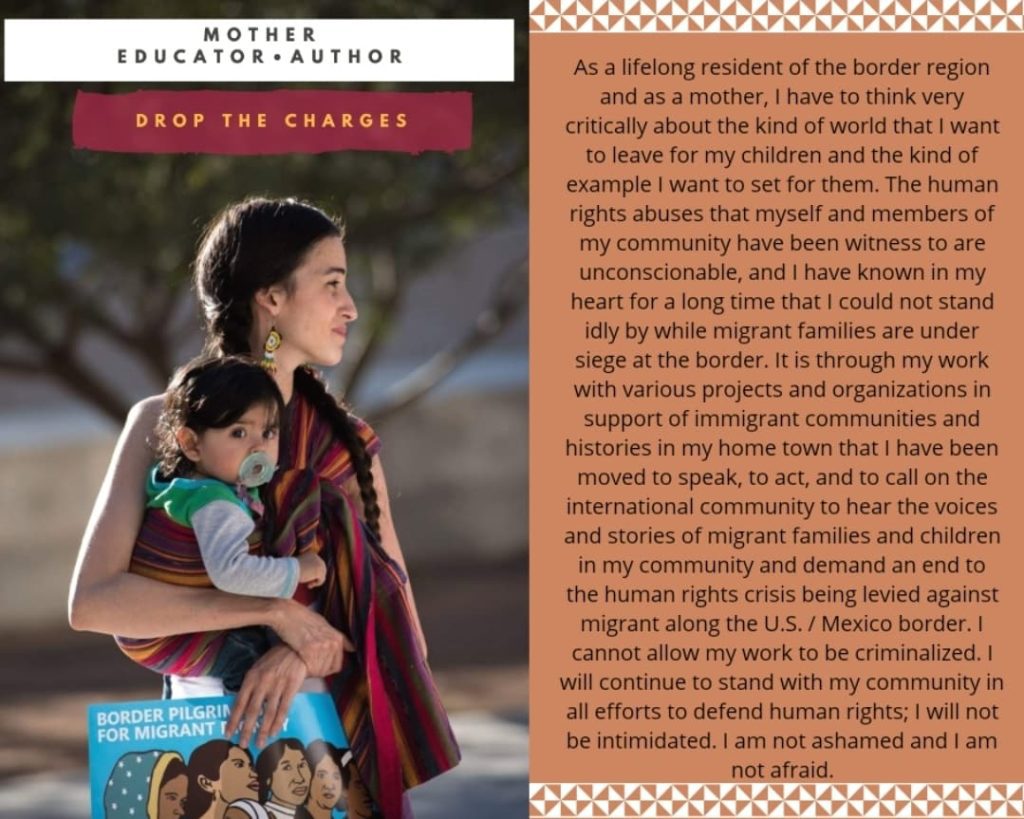

Here Ana, a writer, community educator, and mother of two whose photo is now included on El Paso Most Wanted, explains why the #Borderlands16 activists do what they do.

The deserts and hills of what is now called El Paso, Texas, which we recognize as the ancestral homelands of the Piro, Manso, Suma, Apache and the Tigua and Rarámuri peoples, and which have been built into what they are now on the backs of brown and black and immigrant bodies, have been fertile ground for violence and uprisings and hotbeds for revolution for as long as we can remember. It was from here that the Mexican Revolution was sparked and executed. It was here that the 1917 Bath Riots erupted. This is the nature of Chuco; as long as there is the sickness of oppression in these lands, there will always be resistance in these lands.

Today in this town on what is now the U.S. / Mexico border, we are witnessing another manifestation of this perpetual cycle of oppression and resistance in the exploitation of the lives of migrant families and the communities that have risen to meet it. We have witnessed a series of actions by Customs and Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents that egregiously violate the human rights of migrants and the laws meant to protect them.

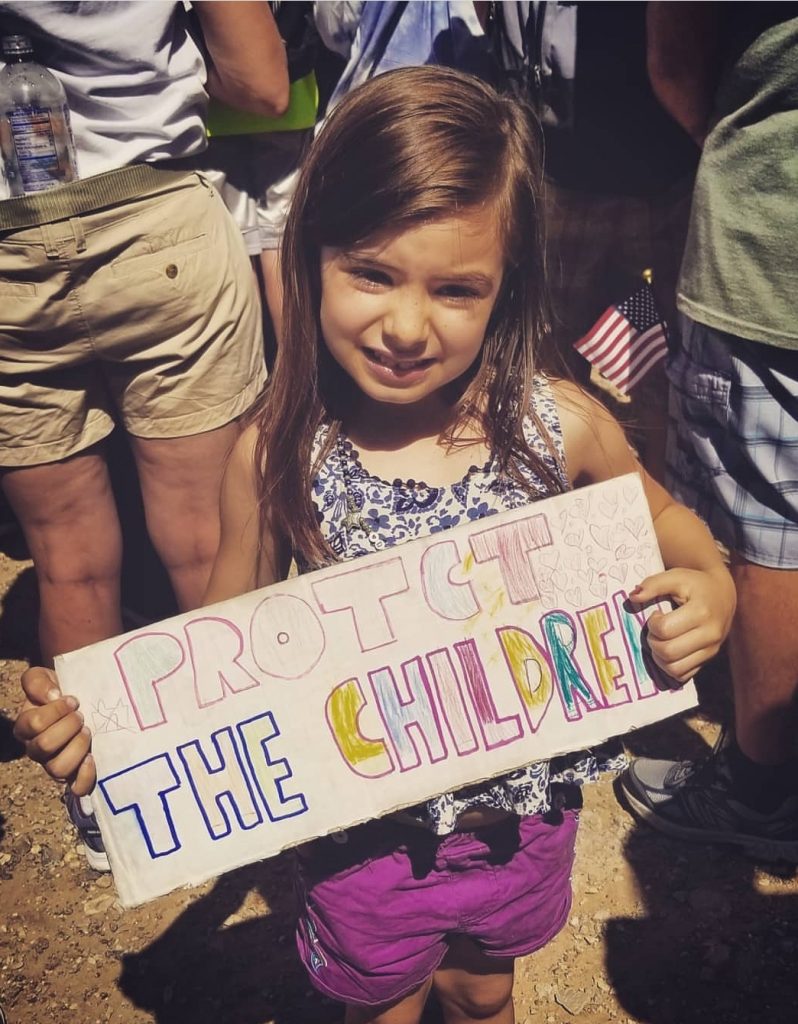

I was present with my little girl, Arcoiris, during the March to Tornillo in June of 2018 just after the Tornillo tent city detention center went up. It was one of the highest turnouts I had ever seen for a local march; later it would be estimated that there may have been up to 2,000 people present that day. The crowd was speckled with celebrity politicians, from Robert O’Rourke and Veronica Escobar from El Paso to, I would learn later, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

At one point the crowd split to enormous applause and Joe Kennedy walked to the stage. Later I would write on watching O’Rourke and Kennedy speak, stating that it read a lot like a photo op for celebrity politicians riding the tragedy-porn coattails of real families who need to be seen and heard, not spoken for. Given O’Rourke’s reputation as a gentrification-friendly double talker amongst the same historical immigrant communities in El Paso that are known for their resistance, it was disconcerting to see him leading a crowd with the intention of defending migrant families along the border, though the presence of O’Rourke and other big-name politicians admittedly drew in a much-needed crowd.

In the wake of the announcement of the “zero tolerance” policy and the increased criminalization of migration, officials reportedly housed thousands of children who had been separated from their parents, as well as unaccompanied minors, at the Tornillo child detention camp over the course of several months. Reports also began to emerge that Customs and Border Protection agents were being stationed at the midpoints of bridges and turning away migrant families attempting to request asylum. Without access to ports of entry and nowhere to go, families were forced to remain in the streets of Ciudad Juárez.

On Dec. 8, 7-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquín died in El Paso while in Border Patrol custody. Then, on Christmas Eve, Felipe Gómez Alonzo, 8 years old, died in El Paso while in Border Patrol custody. That night we heard reports of hundreds of migrants dumped by officials at the Greyhound station in El Paso’s historic Duranguito neighborhood, where residents have led another battle on the streets of El Paso against the gentrification of historic immigrant communities.

Neighbors and extended communities mobilized to collect donations and provide meals and shelter for the families. This would not turn out to be an isolated incident; immigration authorities would continue to leave large groups of families numbering in the hundreds in the streets while the community came together to house, feed, transport, and support in the advocacy of a population experiencing human rights violations.

Then in March, migrant families were found to be caged in a large pen under the Paso del Norte International Port of Entry bridge in El Paso. Parents and children were said to be sleeping in the open air, on gravel, with only mylar blankets for bedding, behind razor wire and chain linked fencing.

When I awoke on the morning of March 31, the heavy overnight winds had broken a window in my home. The house was frigid; the thermometer read 40 degrees and as I checked in on reports from under the bridge, I realized that the public was being told that the families had been relocated, while those who I knew on the ground were reporting that the families had been moved to another location nearby, still exposed to the harsh cold but in a less visible spot.

In the wake of this atrocity, the families that had been held beneath the bridge began to pass through local shelters, including the pop-up where myself and other organizers set up twice a week to serve meals as Food Not Walls. I wasn’t there the night the families who had been caged under the bridge came through. I did hear the stories of my friends and fellow organizers about the horrific conditions they witnessed the guests in that night.

I sat with my dear sister in community, Claudia, in a friend’s house while she told me that as they arrived, they looked like people coming in from a war zone. They were covered in dust, bird poop, and their hair was matted and speckled with rubble. They couldn’t form a line, they only sat at the tables and stared, shellshocked, as volunteers mobilized into a type of triage mode.

One woman told Claudia that her child was sick while they were under the bridge and she asked for medical assistance but wasn’t seen until her child was projectile vomiting incessantly. A lot of the children were vomiting that night. She told me there were points where she thought the children weren’t eating because they were in shock, but then they would run to the toilet and she realized they couldn’t eat because they were so sick.

Claudia gave me a card with a picture of Jakelin Caal on it and told me that this it was to remind me of why we do what we do, and I thought about the way she died, sick in Customs and Border Patrol custody. These are the conditions that children are being subjected to in the United States, while they get sick and we lose them. Juan Ortiz and Cristy Velez, two friends and organizers with Food Not Walls, also shared photographs with me. Cristy handed me the pictures she had taken of the children’s hands, dusty, scraped and bruised from sleeping on the gravel beneath the bridge. Juan told me about a little girl he had documented whose expression had stunned him because she had so much shock in her face as she sat at a table that night.

This is why we do what we do.

I’ve often been in conversation with folks who do community organizing work around social justice issues, and this is what they mean when they say that protest is only 1% of the work. Most of the work is three-hour-long conference calls that end in tears, late-night strategizing and early-morning meetings. The work is collaborative calendars and cooking en masse from our homes and three more phone calls.

But I’m of the brand that understands that protest is also necessary to effect change in moments of particular strife in our communities, such as this moment in which we are witnessing migrant communities in El Paso being treated with a complete lack of humanity by United States immigration officials, government entities, and civilians alike. While these human rights violations are being allowed to continue without consequence, resistance to these actions has been met with heavy criminalization all along the borderland.

On the morning of Monday, April 15, 2019, myself and Elizabeth Vega self-surrendered to the El Paso Police Department after learning that warrants had been issued for our arrest in connection to a 15-minute protest at the Border Patrol Museum in El Paso in February; my charge was listed as criminal trespass. In the weeks leading up to the arrest, the El Paso Police Department held a press conference during which they announced that 16 members of the Tornillo: The Occupation coalition were being charged with state felonies and misdemeanors in connection with the protest, which was one of a series of actions staged over what was called the Revolutionary Love Weekend of Resistance.

A story went around on social media that police had surrounded my old house and tried to arrest the mother who lived there now, believing she was me. My photograph and misdemeanor charge would appear on El Paso’s 10 Most Wanted list, next to people wanted on charges like murder, for two weeks in a row.

Consider this, along with the fact that in the weeks following my arrest, reports emerged of vigilante militia members detaining migrant families, including children, at gunpoint at their camp in Sunland Park. They were said to have been camped out at the site for months, detaining people at gunpoint, and posting videos of migrant families on their knees while Border Patrol agents stood aside. The police were reported to have visited the site and asked the militia, who called themselves the United Constitutional Patriots, to leave the site by the week’s end, meaning that they had several days to stop trespassing. The group was evicted the following day and are said to have planned to relocate and continue operations, however.

If 15 minutes can land someone with a misdemeanor criminal trespass charge and a spot on El Paso’s Most Wanted for a non-violent action, it begs the question: why it is that a group of masked militia members holding children at gunpoint while illegally camped out for months isn’t as pressing a concern for authorities?

As members of this border community, it is our responsibility to witness, document, expose and stand against human rights abuses and the xenophobic oppressions that continue to plague the frontera lands of El Paso. We have a responsibility to the memory of these lands and to the descendants of the peoples whose lands we live on to fight for the dignity of this revolutionary place of desert and mountain and river that we call home.

In jail, I sat in a cell with a woman I’ll call Victoria. She didn’t know where she was, I learned as I spoke to her, and I won’t forget her face when I told her she was in a jail. She told me she hadn’t been fed since the day before. As we shared my chips, she showed me the scars on her head that she had shown to Border Patrol during her self-surrender.

She said she had been separated from her sister, who had also been a victim of a machete attack in Guatemala, and her sister’s children, and brought here alone. “Que es el nombre de este pueblo?” She asked me.

I told her this was El Paso, my home town.

A legal defense fund has been set up for the activists. The coalition asks that all people of conscience help support the effort by donating to their defense at: http://bit.ly/borderland16

Ana Tiffany Deveze aka Ana La Tecpatl is a Xicana writer, community educator, and activist from El Paso who writes about the Xicana experience, motherhood, womanhood, race, sexuality and works to document the beauty of Mexican and immigrant communities of color through poetry, photography, and performance.

Ana La Tecpatl asylum seekers Border Patrol detention camps Elizabeth Vega family separation ICE immigration activism Immigration and Customs Enforcement migrant detention Texas Tornillo

I would like to support you with a check. I don’t do PayPal. Please write me to whom and where I should send the check.

Michael

Wonderful to see your support, Michael. I will write you an email now. Many thanks for reaching out.