One day deep in June 2018 — she can’t remember the exact day because she’d been working seven days a week, 16 hours a day, at least, since April — Jodi Goodwin received a curious phone call. It was from a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deportation officer stationed at the Port Isabel Detention Center (PIDC), where her most recent clients were jailed — all migrant parents. They had fled brutal violence and persecution in their home countries, and survived the perilous journey northward, only to land at the US Southern border just as Trump & Co threw down the gauntlet of “zero tolerance.” Though they were seeking asylum in the US, per their right under international law, Trump & Co shackled them, threw them in prison, and took away their kids.

Now Federal Judge Dana Sabraw, ruling in favor of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in the matter of Ms. L. v. US ICE, ordered that all separated families be reunified by the end of July 2018. However, though the cruel policy had been in practice for months before it was publicly rolled out in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) that spring, there had never been a system for keeping track of who was taken from whom. ICE didn’t have the data to comply with Judge Sabraw’s order.

“So irresponsible,” sighed Jodi. “They had absolutely no plan.”

Family members had been flung to the winds, in many cases incarcerated miles apart. Some parents had been fast-tracked for deportation, turning babies and toddlers, too young to provide a parent’s name or country of origin, into orphans and wards of the US government. They risked being lost from their loved ones forever.

An immigration attorney, Jodi knew the only way to reunite separated families was to spring the parents from ICE prisons first, while simultaneously tracking down the kids, so reunifications could happen as quickly as possible. ICE was desperate for help.

“The officer asked if I’d be willing to share my list that located lost parents and children.”

Award-winning Legal Advocate for the Poor

Jodi landed in the RGV in 1995, right out of law school and fresh from the Texas Bar. She went to Harlingen to fulfill a one-year clerkship with the US Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review. She intended to practice public interest law on behalf of the indigent. But before her clerkship concluded, funding for social programs dried up.

It was the era of Newton Leroy “Newt” Gingrich, a fire-breathing Georgia Republican who was Speaker of the US House of Representatives from 1995–99. Many political wonks lay the death of bipartisanship in the US at this man’s feet. Gingrich had no use for decorum and actively hastened, through scorched-earth attack tactics on his opponents, the polarization that Trump & Co have now honed to a fine “art.”

Gingrich was also the architect of the infamous “Contract with America.” Representing the ultra-conservative agenda still alive in US politics today, it systematically put the interests of banks and businesses over the needs of people, pushing taxes on the rich to a minimum, while shrinking government by gutting services for the elderly, very young, disabled, and poor. Gingrich & Co’s goal then — as it is now — was to return the US to its pre-Great Depression days when there was no social security, no government regulation, no Medicare, nor Medicaid. Some preferred to call it the “Contract on America” as it killed off much of what was considered a public safety net, leaving those caught in the grip of oppressive cycles of poverty to “pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.”

“I thought I’d be in the borderlands for a year, then move back to San Antonio,” Jodi told me. But she didn’t need a weathervane to see which way the wind was blowing. The Gingrich Contract, and other Clinton-era policies, didn’t just harm communities of color, they also placed undue burdens on new arrivals to the US.

So Jodi pivoted. Deciding to stay in the RGV, she hung up a shingle focused on immigration and nationality law.

Jodi believes the heart and soul of every lawyer should be grounded in truth and the search for justice. And, indeed, for 25 years, she has been an integral part of the humanitarian army fighting from the trenches on behalf of immigrants and their families in the US. She has represented thousands of asylum seekers, economic migrants, and long-term undocumented residents seeking pathways to citizenship. She has also held a front-row seat to the increasing militarization of the US border, which caused the country’s for-profit immigration-detention complex to boom.

“There was one detention center in the Valley at the start of the Obama era,” Jodi states. “Now there are at least six.” And that doesn’t include the number of government-funded “shelters” — aka jails for migrant kids.

These changes also spawned the concomitant growth in advocacy services for the immigrant population. But while the work might have been more constant — and more lucrative — if Jodi had joined a firm or legal aid practice, she appreciated the freedom and nimbleness being a solo practitioner allowed her.

Never was her ability to be nimble more important than in the spring of 2018.

Something Wicked this Way Came

When asylum seekers and the US public, alike, were blindsided by Trump & Co’s “zero tolerance” policy and its knock-on effect — the forced separation of families — Jodi was one of the first to act. She was a good three months ahead of colleagues who needed the ‘go-ahead’ of senior partners and/or funders. She was also in a rare position to see the writing on the wall before most others.

From the earliest years of her practice, Jodi has provided pro-bono representation at the public defender’s office in Brownsville. As a result, she knew everyone in the Valley and they knew her, when, toward the end of March 2018, a strange case shift arrived at the courthouse. She began to receive calls from colleagues, all asking the same question: Are we prosecuting asylum seekers now?

Jodi didn’t know, so she went to court to see for herself. There, she discovered adult asylum seekers shackled, though requesting asylum is not a crime. What’s more, they were desperately seeking information as to the welfare and whereabouts of their children. This led her and her colleagues also to ask: Are we taking their kids now too?

On Friday of that week, while attending a colleague’s retirement party, she presciently suggested he wait a little longer to step down. “You gotta stay,” she told him. “We’re going to need you. Something bad has rolled into town.”

He said he knew. It had rolled into McAllen too. Their friends at the Texas Civil Rights Project had sounded the alarm that week as well.

Horror Stories

At the McAllen Courthouse the following Monday, Jodi saw it with her own eyes: “Moms, dads, they were distraught, beside themselves. They couldn’t attend to the proceedings or respond effectively to the judges’ questions. They just wanted to know what happened to their kids.”

According to a second Federal class-action lawsuit, Dora v. Sessions, “Every single parent described the moment that their children were taken from them as the single most vividly horrifying experience of their lives: ‘shattering,’ ‘unbearable,’ ‘a nightmare,’” (p. 12, para 46). Having fled their home countries, in large part to protect their children, they were emotionally and psychologically traumatized at losing them, most cruelly, to men in uniform.

“Dora” fled with and her seven-year-old son after years of extraordinary abuse at the hands of her husband. She arrived at the border and turned herself in to immigration agents, requesting asylum. When a CBP official took her boy, she begged and pleaded, explaining that after all he’d been through, he needed her. The officer told her “she deserved to lose her child and would not see him again until he was 18 years old” (p. 13).

“Alma” was taken to court the day after requesting asylum for her and her two children, aged seven and nine. When she returned to the CBP processing center, her kids were gone. She, too, was told she would never see them again: “that they would remain in the US and she would be deported” (p. 14).

Likewise, “Esperanza,” whose husband “gifted” her to a MS-13 gang leader as a sex slave, ran to save her son, who witnessed her being raped too many times to count. A CBP officer told her, “he belongs to the US government now” (p. 17).

Herself a mother of three, as well as a fluent Spanish speaker, Jodi understood their stories — and their pain — on a deep level. She obtained the “Alien” Identification numbers (A#s) of seven women in court that first day. She followed them to PIDC where they’d been sent. She told them, “I’m going to get your children back.”

She hoped she could.

Article 14: Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Asylum is an international human right codified by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and written into US law in 1980. Typically, once asylum seekers are processed by CBP, they are remanded to a “sponsor” — someone who agrees to support them financially and get them to their court hearings on time — while their claims are adjudicated. The process can take a year or more to conclude, but the data show that this system, dubbed “catch and release,” works 98% of the time. Stands to reason. No one wants to live undocumented, in hiding, and unable to work if they don’t have to.

Even before the 2016 election, however, Trump & Co claimed, without evidence, that “catch and release” allowed too many “alien criminals and rapists” to run rampant in the US. Intent on ending the practice, they resolved with “zero tolerance” to criminalize all migrant arrivals at the US Southern border — even asylum seekers. And because US law states that criminals cannot be trusted with their kids, Trump & Co took the kids away.

“The system has never been fair or humane, not under Clinton, either Bush, or Obama. But ‘zero tolerance’ brought a new level of cruelty to US immigration that I had never witnessed before,” said Jodi.

“A body politic that will separate families will stop at nothing.”

Introducing: The US Immigrant Pipeline

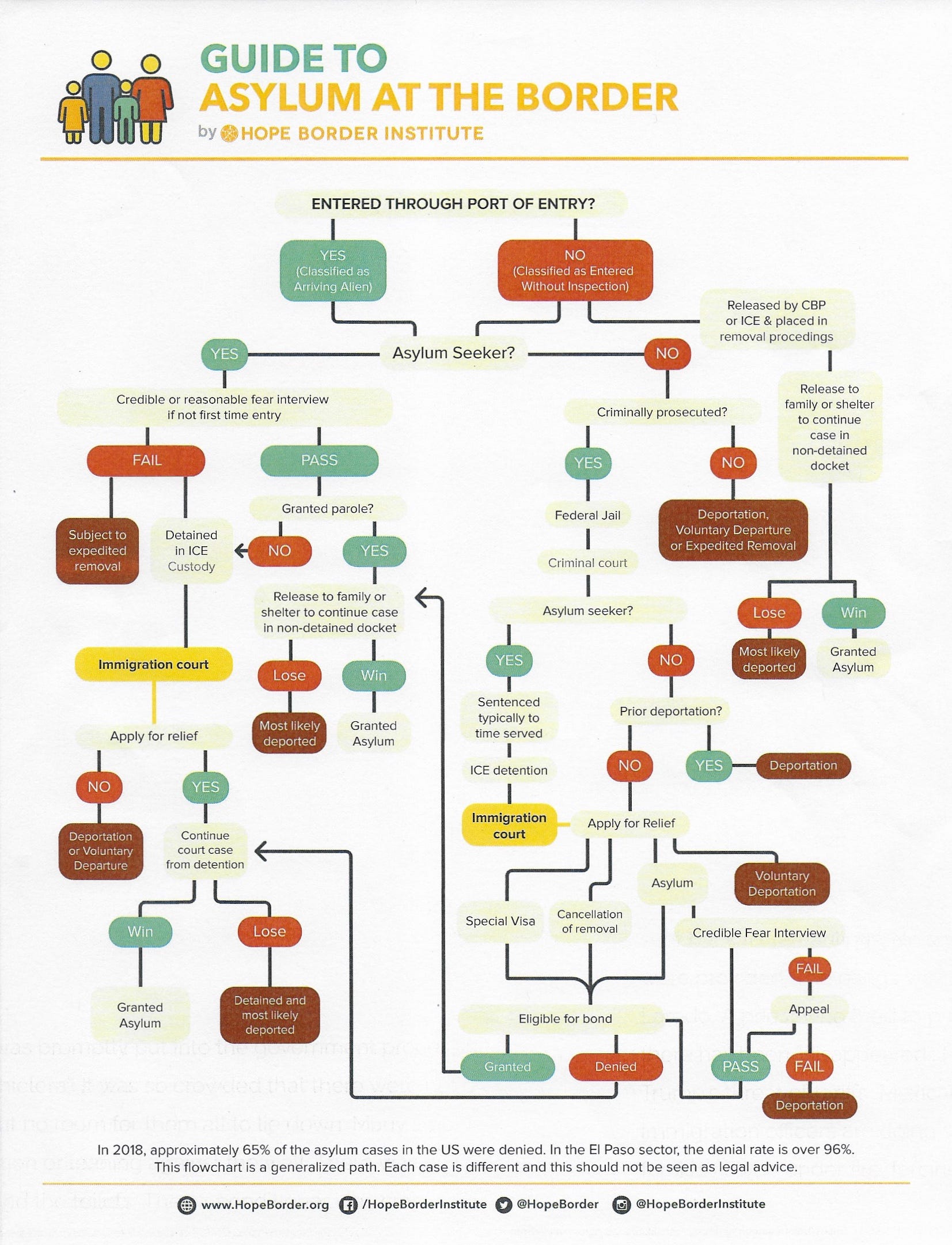

On arrival in the US, migrant minors and adults are funneled into two different pipelines, each including its own alphabet soup of agencies, which are not in the habit of talking to one another. That might not matter in the case of individuals arriving alone, but when it comes to separated parents and children, reunification becomes next to impossible when information is not routinely captured and shared.

All migrants’ first point of “welcome” in the US is the CBP. Once in its custody — what the agency refers to as an “apprehension,” whether a person is caught crossing the border illegally or has lawfully requested asylum — all are taken to a processing center, like Ursula, aka la hielera (the icebox), in McAllen. There, they are sorted by age and gender, and transferred within 72 hours — when the system is working — to detention. Adults are handed off to ICE, an arm of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), while children are passed to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Following the rules laid out in the 1997 Flores Agreement, children must be moved from detention within 20 days and placed with a parent or other relative. But many of the children taken from parents in the spring of 2018, had no one to go to. The parents they’d arrived with were now in prison. That’s why Jodi’s priority was to get the parents out, and as quickly as possible, before the ORR “system of care” kicked into gear to place their children in foster homes or lose track of them altogether, maybe for years.

At the PIDC, she emptied her pockets and purse of car keys and cell phone, passed through the metal detectors, then spread-eagled her arms and legs for a wanded “pat” down. She approached the clerk’s security window and pushed seven forms through the gap between glass and narrow formic-topped counter, each one filled out with the A#s of the seven parents she’d come to see. Then she settled into a hard-backed, immovable chair in the cheerless, institutional, high-ceilinged waiting room where there was nothing to do but watch someone else’s choice of movie from a soundless TV screen.

Jodi met with all seven mothers that day. Each recounted her story — slowly, haltingly, wiping away tears that would not stop flowing — of her last moments with the lost children. Jodi carefully recorded what details they could remember, taking down their names as well as the names of their missing kids; their country and town of origin; the names of their CBP handlers; etc. By the end of the day, Jodi held not just these seven horror stories: She also learned that inside the PIDC there were at least four dorms of 70 women each, all of them robbed of at least one child.

That meant 280 women and many more children needed representation! And this was just one detention center!

She asked herself, “How am I going to be able to find all these kids.” Leaning always on the “minors’ right to protection” argument, ORR shields itself from scrutiny and its inmates from view. It is impenetrable, even denying clients’ attorneys from knowing the names and locations of their detainees.

“I wanted to cry,” remembered Jodi. “But there was no time. There was too much work to do.”

She knew she couldn’t manage that many cases. “Most lawyers handle about 25 cases a year.” But by the end of the summer of 2018, Jodi had single-handedly reunited 34 families and played a significant role in bringing 450 families back together again. Even during her own family’s summer trip to France in August, she was working on reunifications.

It Takes a Nation

After that first meeting at PIDC, Jodi gathered her networks. She called on Kimi Jackson and the South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project (ProBar) to help locate kids. She joined her list of names with those being collected by the Texas Civil Rights Project and RAICES: the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services. In all, she organized 250 attorneys and legal advocates from all over the nation to provide pro-bono support for the broken families.

She took depositions, wrote briefs, completed 589s, advocated on behalf of her clients with ICE, argued their cases, mentored others to argue cases. Her mission was to make certain all asylum-seeking parents separated from their children had a fighting chance at getting their kids back. She did all this while single-mothering three kids and without taking on a paying client for nearly four months. Jodi grew so broke that when a water pipe burst in her house one long weekend when she and her kids were away, leaving it damaged down to the sub-flooring and in need of a gut-renewal, she had to move them into a rented two-bedroom in town.

They had only just moved back into their own house a week before Jodi and I finally met, in June 2020. Putting family reunifications before all things, it had taken her nearly two years to afford her home renovations.

When I called her a hero, she demurred. “I was just the impetus. The heroes are everyone who pitched in.”

Sadly, not everyone found each other again. Pressured into signing papers they did not understand, some parents were deported before their kids could be found. Facilities, like Homestead and Tornillo, were erected on Federal lands, where Trump & Co could claim exemption from Flores regulations. Kids were incarcerated there for months, many used as bait by ICE to ferret out undocumented relatives. When these people, too, got deported, it left too many youth with no family to go to. Some were sent to foster care; others languished in ORR’s “system of care.” They are many still on the inside today, unknown, forgotten.

All told, Jodi managed 37 reunifications on her own. The last one took 16 painful months. “Ace” was five years old at the time he was forcibly removed from his father “Felix.” When he first laid eyes on Felix again, he was almost seven and didn’t recognize his own dad. Felix’s case was originally denied by an immigration judge, but remanded to the Board of Immigration Appeals. Jodi took the case over then. “I won it on the second try before the IJ.”

It took another two weeks after getting Felix out to extricate Ace from the “tender age” facility that held him just up the road in Raymondville. Trump & Co alleged there were “security” reasons why father and son could not be reunified again, but gave no explanation or evidence.

“The reunion was very difficult for me to watch,” said Jodi. Just talking about it had her in tears. Though it had been over a year since she had succeeded in bringing Felix and Ace together again, remembering the incident triggered the trauma she had felt, and carried, for all who’d been caught in Trump & Co’s tragically tangled web.

“The tears. The silence. The confusions. The inability to recognize the parent. The fear. The disbelief. Oh! The pain in the Felix’s eyes, fighting back tears just hoping Ace would recognize him. It was the worst emotional trauma I’d ever seen,” recounted Jodi, who throughout the ordeal had, out of necessity, transformed from attorney to family mediator, too.

“It took a long time for Ace to warm up to and trust Felix again.”

No Rest for the Weary

Though the forced separation of migrant families stopped with the June 20, 2018, executive order, Jodi’s work did not. In addition to continuing to knit broken families back together, a second knock-on effect of “zero tolerance” meant there were now mouths to feed.

The practice of “metering” — a new take-a-ticket-and-wait-in-line system of processing asylum seekers — had been put into place also that June, causing a scrum of people to back up on the Tex/Mex bridges. This sparked the creation of the Angry Tías in Reynosa and Team Brownsville in Matamoros, both of whom, like Jodi, stepped up, unexpectedly, to see to the common good in the face of deliberate government cruelty.

In mid-January 2019, Jodi and her extended family joined Team Brownsville to provide meals for asylum seekers camped out on the Gateway International Bridge.

“We did Sunday dinner each week. We took turns cooking a main, a dessert, a side-dish, and my daughters and I would drive into Brownsville and take the food across. We’d bring bubbles and chalk for the kids, crayons too.”

By the fourth Sunday, the asylum seekers had clocked that Jodi was an immigration attorney. “I started getting flooded with questions.”

Week after week, person after person, the questions all started to sound the same. And it would keep Jodi and her kids in Matamoros for hours, well after dark. It was unsustainable.

She reached out to the Team Brownsville leadership: “What do you think about my doing an after-dinner group talk each week at 7pm. We’ll call them charlas” — the Spanish word for chat. “I can make sure they know their rights, and what documents they’re going to need; I can walk them through what to expect from a Credible Fear Interview, and help them fill out their 589s…”

That’s when Jodi transformed again.

Introducing: Street Lawyering

It started with 50–100 people, then grew to 120, then 150. By June 2019, Jodi was advising 200+ people on Sundays, in addition to her regular weekday caseload. It was already unmanageable. Then, in late-July, Trump & Co threw down the gauntlet again: This time the Migrant “Protection” Protocol had rolled into town, slowing asylum hearings to a trickle and stranding asylum seekers on the wrong side of the border — the dangerous side — for months on end. The refugee population in Matamoros grew from 200 to 400 to 1200 to 2000, seemingly overnight.

Jodi gathered her troops again. “I sent email after email. I posted on Facebook. I asked lawyers of all stripes for their pro-bono support. Eventually, I amassed a small, fierce, committed battalion of legal advocates to join me in Matamoros to do street lawyering.”

At first it was local attorneys, working weekends. Then contacts from all parts of Texas and the country swooped in for a week or two at a time. Just in time too.

“There were hundreds and hundreds of people. We were swarmed.”

Among those who came were Traci Feit-Love and Charlene D’Cruz of Lawyers for Good Government. On seeing the need, they decided to set up an office and to keep Charlene in Matamoros full-time. In October, 2019, she moved into the Resource Center Matamoros, and took over all that Jodi and her humanitarian army had been doing on the street: know-your-rights workshops, screenings, translations, document prep, 589s. This left Jodi, now part of the Dignity Village Collaborative, to represent asylum seekers in the kangaroo tent court, which I observed in January 2020.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, and Trump & Co, while insisting it was a “hoax” elsewhere, allowed the virus to do their dirty work for them. They swiftly closed the Southern border due to COVID-19.

“My last day in court was Friday, March 13, 2020.”

Introducing: The Rona-Sabbatical

Now on an imposed “rona-sabbatical,” Jodi, like Charlene, continues to chip away at the stone. Though the number of refugees in the Matamoros encampment has thinned to about 1500, that’s still 1500 cases left to process and win in court. When the US border opens up again, Jodi and Charlene intend to be prepared.

“We’re going to bombard the courts with asylum seekers who know the law and have iron-clad case-files.”

When we spoke in June 2020, Jodi already had 34 successful cases behind her for the year, and 27 new cases ready for trial. She was self-isolating with her horses and three kids back at their newly renovated, though yet to be redecorated, house on her beloved Ranchita, a 20-minute from Harlingen in the Texas countryside.

“It’s the perfect place for a Rona-Sabbatical!” Jodi exclaimed.

It’s rare to meet a person so positive. That said, as soon as she was able to stop to take a breath, Jodi crashed. The months and years of dealing with trauma victims, feeling their pain, empathizing with their anxiety, holding their depression, had taken its toll. Then, suddenly, she was at home, schooling her kids, napping in the middle of the day, slipping into her cowboy boots instead of her lawyer’s heels, and loving the “break.”

We discussed how family separation — a potent tool of dehumanization exploited by racists and fascists throughout time — is another aspect of the Black Lives Matter movement. The practice has deep roots in our nation’s history. From selling children right out of the arms of their enslaved parents to kidnapping Native American youth and stripping them of their cultural heritage in abusive boarding schools, Trump & Co have now harnessed family separations to inflict deliberate cruelty in order to send a message to others: Don’t come here. You are not welcome.

No matter the iteration, the practice of family separation strikes a terrible blow and exacts a terrible cost. The psychological impacts of ripping families apart are devastating, not just for the individuals, but for their communities and their nations…for generations.

“Why do you think they did it?” I asked, turning our charla to Trump & Co’s motivation. “These are members of Gringrich’s GOP — devotees of ‘small government,’ who’ve bloated the budget to build a boondoggle wall as well as to incarcerate innocent kids and their parents, indefinitely, at US taxpayers’ expense, and for the ‘crime’ of wanting freedom in the ‘land of the free.’”

“It’s a narcissistic play for re-election,” said Jodi. “They did it to feed the hate of the right-wing voter base, who don’t care if Black and Brown people are tortured.”

“I know,” she added. “Because these are my people.”

It turns out, Brendon Tucker isn’t the only redneck revolutionary I met in the borderlands, who is now devoted to bringing dignity to the victims of Trump & Co’s cruelty. Jodi hails from Old River, Texas, a small town of roughly 350 people located not too far from Jasper, where its KKK is remembered for dragging Black people from ropes behind trucks. She grew up with this now MAGA-hat-wearing crowd, but left home as soon as she finished high school, winding her way through the big blue cities of Texas before settling down in another small town, six hours south of Old River, and an hour from the border.

“But you can never really run away from your roots.” You have to live with them, love them, and, Jodi hopes, lead them to see humanity in all people through the actions and deeds you model.

That is precisely what Jodi has dedicated her life to do.

Sarah Towle is an award-winning London-based US expatriate author sharing her journey from outrage to activism one story of humanity and heroism at a time. Check out her stories on the Angry Tías and Abuelas, Redneck Revolutionary Brendon Tucker and human rights hero Jennifer Harbury. This is Episode 14 in her travelogue of a road trip gone awry: THE FIRST SOLUTION: Tales of Humanity and Heroism from Trump’s Manufactured Border Crisis, rolling out on Medium as fast as she can write it — because, in Sarah’s words, “it’s Just. That. Urgent.”

Border Patrol family separation ICE immigration Jodi Goodwin Rio Grande Valley

I have been following this since the beginning and cannot believe that anyone would commit such abuse against families and children. I read recently where a man was sent to prison for caging children in dog crates. Surely this should apply to Trump and his cohorts? These are human beings who have already been through hell and now are separated? I also understand that children have been physically abused, neglected, used for trafficking and goodness knows what else by ICE. I fear for friends from El Salvator and their children. I am an artist and am currently working on a series of abuse of power and its effects.

Thank you so much for writing, Edwina. Your paintings are quite beautiful. I hope you will stay in touch and let us know when your series is finished. Perhaps we could do a photo essay.