As Odysseus prepared to depart to the Trojan War, he left the supervision of his son Telemachus’s education to an old and trusted friend, Mentor. Many of us have had the gift of a mentor or mentors, whose words and deeds coupled with a personal relationship have guided and inspired our lives and our activism over time. We are now at a time that calls for, as Rafael Jesús González says, “a revolution of mind and heart for justice, rooted in compassion, for peace, for the Earth, for Life.”

This is the first in an occasional series of essays by climate activists, designed to showcase insights and wisdom gleaned from such mentoring relationships that could provide us with the skills, tools, knowledge and ideas to assist in imagining a coherent and powerful way forward. Such insights and counsel may come from the wealth of diversity that exists in those who have or are mentoring us.

What do a WWII combat general, a brilliant nonviolent strategist, a Berkeley poet laureate and activist, and a German master puppeteer/ bread maker have in common? All were my mentors and all have impacted my thinking as to how to address the climate crisis. I am acutely aware that what they have in common is their gender, all are men. I have had many women important in my life who have provided me with teachings, guidance, insight and the like. Unfortunately, I have not benefited from a woman whom I would consider my mentor. Hearing from a diversity of mentors is necessary to help inform our collective thinking on how to move forward.

Major General Earnest N. Harmon

My relationship with Major General Earnest Harmon, a tank battalion commander from the WWII Battle of the Bulge, began in grade school when introduced through a relative. My first gun, a 22 caliber / 4/10 shotgun, was an unexpected gift from the general. I was a young boy in Vermont, growing up in a town housing the only private military university in the country, Norwich University. General Harmon was the president. Over the coming years, he paid to send me to camps, upgraded my gun collection, invited me to work for him at his Lake Champlain farm and camp.

Photo: https://1.bp.blogspot.com/

In his study, I was in awe of his trophies, commendations, photos and artifacts from World War II. He said that I would someday make a good soldier. My relationship with the general ended the day I turned down an appointment to West Point Military College that he had helped facilitate. His impact on me, however, did not end there.

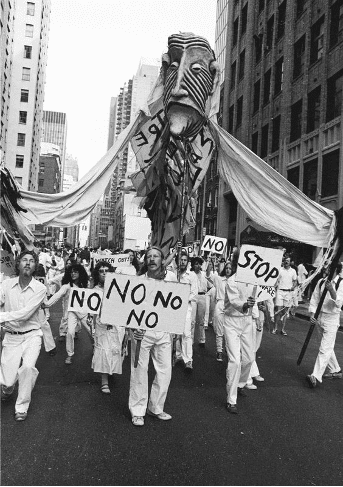

Peter Schumann

Thirty miles away, in the town of Plainfield and at Kate Farm on the campus of Goddard College, another mentor was plying his trade. Peter Schumann, founder of Bread and Puppet Theater, had developed a craft to feed the people’s bodies with his wood-oven rye baked bread while feeding their souls with puppetry.

Before you disregard puppetry as inconsequential, note that these ‘puppets’ ranged from intimate flea circus-sized inanimate objects to 20-foot-tall animated figures who crossed tens of acres of land being performed by a troupe of talented musicians, dancers, activists, and puppeteers. As an immigrant from Germany in the early ’60s, Peter developed a genre of political theater and community action that continues to resonate and be replicated throughout political discourse in the United States and around the world.

I first volunteered with Bread and Puppet when I was 20 years old. I was

introduced to stilting, giant puppetry, bread baking, pageantry, the use of skillful humor, fierce imagery, collective choreography, found object creations and Cheap Art. I recognized a master orchestrating a whole new world of communication, activism and power.

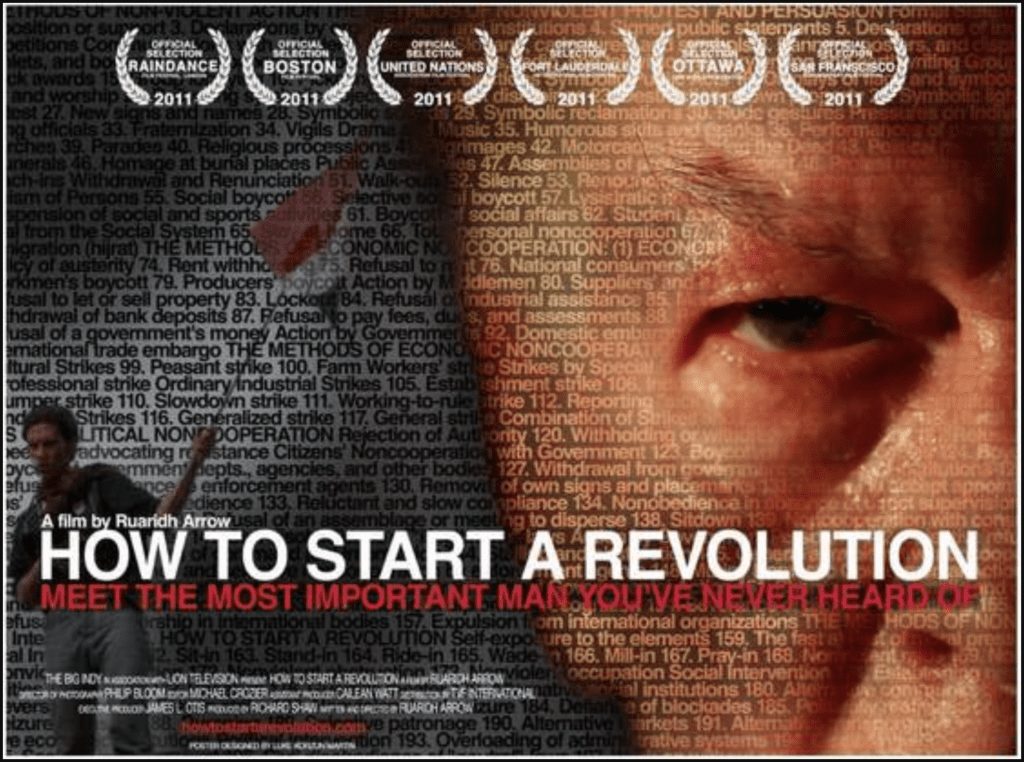

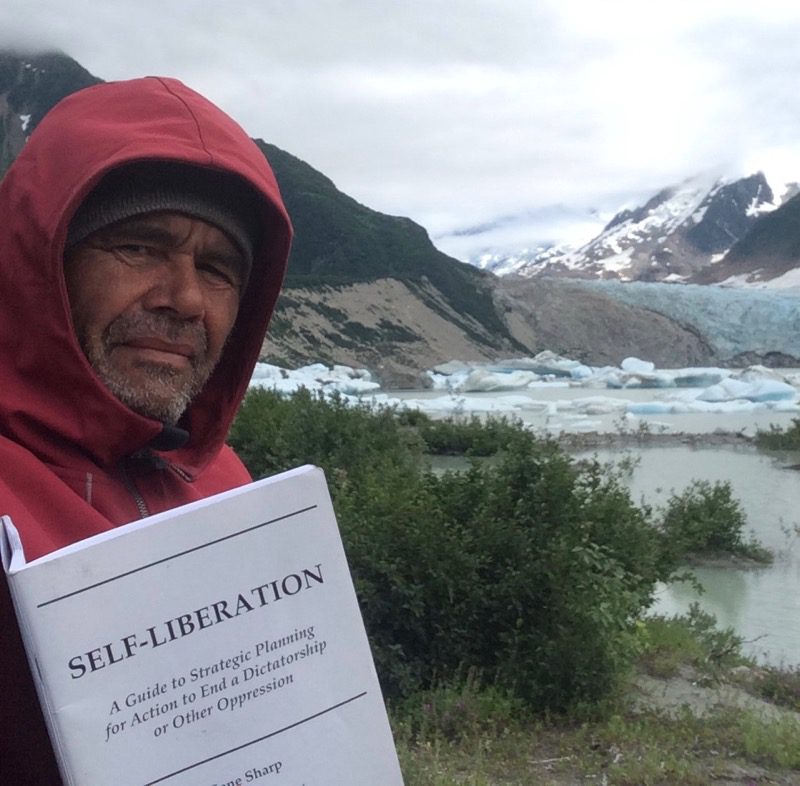

Gene Sharp

I was 21 and struggling with the concept of pacifism. I was opposed to war. I was also opposed to unbridled power. Vietnam was in its death throes and I struggled with making sense of it all and of my relationship to war.

Photo by Conor Doherty

If you study the theories and strategies of classical warfare, you will examine the

foundational work of Carl von Clausewitz. If you study the history, theoretical

underpinnings and methodologies of nonviolent action, you look to Gene Sharp and the Albert Einstein Institution. As fate would have it, I had an opportunity to hear Gene speak in Vermont in 1974. He opened to me a whole field of understanding of how people can and have fought oppressive systems, fascism and dictatorships nonviolently.

From a long conversation following his presentation that night to his death in January of 2018, my four-decade relationship with Gene and his profound work led my thinking and actions on the nature of developing power through nonviolent action. It still does.

Rafael Jesús González

Rafael Jesús González had been flown to Salt Lake City to help organize the

1983 International Day of Nuclear Disarmament, he from activists protesting California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and I from New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratories anti-nuclear weapons. The first evening together, we walked the streets and giddily woke a friendship and mentorship that continues to this day.

Rafael is a fierce wordsmith, impassioned frontline peace and justice activist,

cross-cultural ambassador, spirited and spiritual leader with deep Meso-American roots, and an exceptional practitioner of arts for cultural transformation. He is currently Poet Laureate of Berkeley, California.

So, what might these four mentors have to offer regarding actions we could take to help mitigate the climate crisis?

We are now facing an existential moment on this planet, Earth. Having now

entered the Anthropocene Epoch, the current geological age determined by human activity’s dramatic impact on climate and ecosystems, humans are left to either change direction or continue on the path to ecological disaster. Although this assessment is undisputed by the vast majority of climate scientists, what is not so clear is how the enormous systematic and structural changes required to mitigate our collective future can occur in a compressed timeline. I am looking to my mentors for insight.

What might General Harmon say?

General Harmon was a military strategist at heart. From being educated at the United States’ top military university, West Point, to his role within the only horse-mounted cavalry unit engaged in warfare in WWI, and to several high level command appointments in WWII, the general was steeped in warfare like few others.

I believe that the General would say that if a nation is threatened by forces that are jeopardizing its existence, going to war is the only option. But if you are going to war, you have to be smart about it. You have to be strategic. You have to know the strengths and the weaknesses of your opponent. You also have to assess your own strengths and liabilities.

Once such an assessment is completed, you must create an overarching

Strategic Plan to lead your forces. Warfare is messy and no plan will go undisturbed, and so continual adjustments and recalculations are required to lead to victory. Being flexible, utilizing a wide range of weapons, knowing timing and correct choice of methods, obtaining accurate analysis, while keeping true to the original objectives — all of these are hallmarks of successful campaigns.

The climate situation calls for building sufficient strength to develop sufficient force to demand choices that must be made to mitigate and adapt to the enormous challenges of climate disruption.

How might Gene Sharp’s work support building

the power of the Climate Movement?

Gene’s almost seven decades of deep research into historical cases of the use of nonviolent action led him to foundational understandings of the workings of nonviolent resistance. Identifying 198 methods of nonviolent action was critical to seeing underlying patterns of struggle. His research confirmed the power of nonviolent action and provided practitioners with sound advice in analyzing opponents while strategizing future actions. Gene’s writings and workshops have been credited for inspiring tactics and strategies from the Serbian overthrow of the dictator Slobodan Milošević, to the resistance movement in Burma and the Spring Uprising in Egypt. Ultimately, Gene stated again and again, all power is held by the people. No government, even dictatorships, can maintain power without the consent of the masses.

After a lifetime of research, Sharp was quite clear on how to best grow power.

Although there have been many instances of creative and resourceful spontaneous nonviolent responses to oppression, it is critical for any movement that wants to build significant power to do its “homework:” to develop a strategic assessment of its opponents, of its own organizational strengths and weaknesses, of the history and environment of the struggle, of potential allies, weaknesses in the pillars of strengths that support the opposition, and of resources available to its fight. Sound familiar?

Dr. Erica Chenoweth is a political scientist who surprised herself when she was challenged to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of nonviolent versus armed struggles over a 100-year period of maximalist struggles based on 300 cases. Nonviolent resistance campaigns showed they had a 50% success rate and armed counterparts had 23%. (Gene would add that many of these were done with limited strategic and long-term planning).

Dr. Chenoweth research identified 4 key elements in successful nonviolent struggle.

Campaigns proved to be successful if they…

1) Build large and diverse participation

2) Provide pathways for defections from those often affiliated with the pillars of the opponent’s support

3) Maintain nonviolent discipline even under extreme stress.

4) Draw from a wide range of nonviolent methods.

Perhaps the most noteworthy of her research was the conclusion that every

campaign that was able to get 3.5% of the population actively engaged in the movement succeeded. That’s 3.5%.

The implications from this for the climate movement may be that we must look toward a coordinated, diverse campaign, led by deep strategic thinking and planning with the intent to activate and motivate 12 million citizens to nonviolently fight for climate mitigations.

What have I learned from Peter Schumann and the Bread and Puppet Theater that have implications for the Climate Crisis?

Bread and Puppet Theater was born in the streets of New York City in the

turbulent 1960s. It engaged the community with arts projects, children’s art education and protests against landlords, rats, and unethical police. As the Vietnam War protests grew, so did the size and scale of the puppetry. Being the most audible, visible and colorful contingent of protestors, the theater developed a range of handmade and accessible props, puppets, and banners to make succinct messaging that was clear, crisp and provocative. It was not unusual for them to have hundreds of volunteers participate in blocks-long processions.

There are several aspects of Schuman’s work that could have direct implications

with building a more diverse climate movement. Community organizing, fundamental utilization of the performing and visual arts, humor, free public events, clear messaging, creative imagery, and sustainability are among those to be noted.

The Climate Movement must grow, and it must grow its diversity and involvement. Although the culture of Bread and Puppet has primarily appealed to more alternative audience/participants, the core organizing principles are adaptable to any community organizing efforts. They build community, enchant people, provoke the imagination, directly confront issues, and promote actions to address such concerns.

In 1974, the theater moved to northern Vermont for its new home. Large enough to handle peak crowds that grew to 15,000 daily, the land also provided the means to grow food, harvest maple syrup, cut firewood, harvest grass hay, and raise chickens.

Celebrating the abundance of the Earth and the need for increased self-sufficiency are core to a message of a responsible response to future resource disruptions due to climate. It is imperative that communities begin to identify strengths and weaknesses in their food, energy, water, housing and emergency response systems. This would entail such steps as community-based energy generation and storage, enhancing local agricultural production, storage and processing of food, securing water sources, storage and infrastructure, and securing emergency services.

What have I learned from Rafael Jesús González?

Rafael recently reminded me, as he often has, of the advances that have been

gained through unified, progressive, collective actions. President Biden’s increasingly informed positions and actions on climate are the result of organizing by climate activists, indigenous communities and the acknowledgement of the ‘existential moment’ we face presented by the climate crisis. Community organizing is the key to such pressure that results in real gains.

Rafael’s activism amplifies how the Arts have always played a crucial role in social movements. Visual and performing artists have been critical crafters of the message, framers of the issues, educators of the masses, and inspirers of great things.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Rafael’s impact on addressing the climate crisis for me has been his spiritual connection with the Earth. Based on indigenous roots in Earth-based spirituality, his dedication to the defense of our planet consistently honors our relationship with the Earth’s extraordinary, intelligent and sacred web of life. Throughout the planet, the indigenous movements seeking to protect Mother Earth have been the leading voices and physical defenders of the planet. Awakening our human awareness of our reliance and responsibility to Mother Earth from our slumbering minds and acting in defense of all life is in every person’s DNA.

Summary

The planet Earth’s capacity to maintain homeostasis, a relatively stable state of equilibrium that can support life as we have known it, is looking more and more tenuous without fundamental changes in human activity. Such changes require massive pressure built upon human power to force the systematic and structural shifts. From these mentors, I have come to value the following ingredients of a way forward that would hold some promise for mitigation of the climate crisis.

- We are in an undeclared war on the climate that must be met with the same

serious and calculated responses as declared wars in the past. - Nonviolent direct action, strategically employed, must be the cornerstone of resistance.

- Diverse community organizing, Arts integration, and building resilience into our community systems of food, energy, water and shelter are keys to moving

forward. - Honoring our spiritual connection to the web of life and recognizing the

leadership of indigenous communities in the climate fight for justice are central to addressing our increasingly painful relationship with the Earth.

These observations and gleanings are offered as provocations toward actions

that could make a difference. In this complex world, the need for diversity of

possibilities, anchored in traditions and elder voices, may provide the insights and inspirations for the disheartened and the enlivened to forge a coherent path forward, together.

Are you a climate activist, or do you know one? If so, this message is for you (or them): Is there a mentor or mentors who have inspired you in your path as an activist? If so, we invite you to explore your relationship with that person and his or her impact on your life and your work. Write to us at [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you, and perhaps even work with you on an article for this series.

Bread and Puppet Theater climate activism Earnest Harmon Gene Sharp mentors Peter Schumann Rafael Jesús González

Climate Crisis is as serious as a World Wide War ….it is however of relevant importance – for us to fight properly – to first clearly identify who is our enemy !

Being raised in a military environment of Generals with Cadets armed with rifles , including bayonets parading with Fully Armored Tanks for the sake of training for “Combat with The Enemy ,” I was enthralled with the honor of feeling safe with all that Power and discipline on display!

My first funeral was a Vietnam Vet from my home town! Opened a new window in my heart and mind. Senseless draft of classmates , nightly news of massacres of complete families. Not just Soldiers, I chose pacifism by practicing sit ins anti war movement and supported Communal living hoping to make a difference In humanity with peace as a mission. For 15 years of my childhood I lived off grid at our summer lake home! Wild berries , fresh caught fish and vegetable gardens with cold water springs serving as a refrigerator, I was taught sewing with a treadle machine and canning of fruit and vegetables for year round consumption for our family of ten!

Completely unaware of the value of that education until I raised my own family on a 150 acre hilltop ranch on a 7000 acre lake next to a state park!. Total peace and nature’s provisions filled our lives.

Man and nature need to be intimate in order to understand preservation for future generations!

Nature offers us energy if we maintain respect for each other.

My father, Leo Brassard, who built the home of General Harmon of Norwich University, was a strong yet peaceful mentor for myself as well as anyone who met him. He was a veteran who found his peace and Joy working hard teaching others appreciation for the earthly provisions and blessed my mother with Nature’s fruit. He said Every Day should be Earth Day! An Earth that lives in Peace and productivity! Just apply Elbow Grease and Tulip Salve!

I would enjoy supporting the Esperanza Project! Save this world for my 12 Grand Children!

Thank you, Cecile, for your eloquent response. What an interesting connection! I am passing this along to the author, John MacLeod. Many thanks for taking the time to reach out to us. We will write to you personally.

Greetings, Cecile-I appreciate your writing and background. You were indeed fortunate in having such a father to guide and inspire you. I think your insight that “Man and nature need to be intimate in order to understand preservation for future generations” is a critical piece to the baffling response to a clear knowledge of our need to dramatically shift our collective lives to ensure a liveable world for our children’s future. Thanks for taking the time to respond.