By Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez

Production by Alan Zambrana, Solange Castro Molina y Carlos Andrés Idrobo

As the pandemic rolled out across Bolivia, one community stood out in their response to the virus. The Kallawaya – an ancient herbalist community of itinerant healers known as the doctors of the Inka – spread an image of hope through the crisis with their red striped ponchos and bags full of healing plants.

This series of stories is a part of Legacy of the Andes, the long-awaited second part of the Cosmology & Polycrisis transmedia series, produced by The Esperanza Project with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The One Foundation. Watch the accompanying film, read related stories, download the book and explore the entire transmedia series here.

With an estimated 980 different plants in their botanical pharmacopeia, the Kallawaya have developed their healing arts over the millennia in the mountains of the Bolivian Altiplano northeast of Lake Titicaca, up to 4,200 meters above sea level, earning UNESCO recognition as an intangible cultural heritage. From that rarefied atmosphere they have traveled the world with their bags of herbs and esoteric spiritual medicine.

The Kallawaya have been distinguishing themselves as accomplished healers since at least 400 A.D., performing brain surgery as early as 700 A.D. Some historians credit them with being the first to discover quinine, an alkaloid extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree, to treat malaria and other tropical diseases; indeed, these traveling medics earned a place in history during the construction of the Panama Canal, where they saved thousands of lives with quinine before the Western world had developed a cure for the devastating disease.

Para leer esta historia en Español, vea Los Kallawaya: Los Médicos de los Inka

As part of their service to humanity, the Kallawaya have a long tradition of traveling throughout the continent, collecting new medicines and providing their healing arts to people. Azucena Paucar Pari, the daughter of a couple of those traveling medicine people, was born for times such as these. She has been absorbing the healing arts since before she was born.

“I would say since conception, when I was still in my mother’s womb,” as she proudly says. As a toddler, her father, Abelino, and her mother, Elena, would take her to tend to the medicinal plants and to harvest them. She learned how to plant the medicines and care for the animals that would be used in mysterious healing rituals. She also learned the importance of making offerings to the Pachamama, following the Andean concept of Ayni, or reciprocity.

For the Kallawaya, as for all Andean peoples, this basic principle is one of several that underlie the Andean cosmology: giving back to the Earth, and to the community, or Ayllu, of which one is a part. The Kallawaya sense of community is global, however, as well as local. Azucena’s father Abelino, has traveled to Europe and all over the Americas. And many, like Abelino, move to the cities where they can share their knowledge where it is needed.

Soon her students and their parents began to get sick, and as in the entire city, the situation in his educational community became critical.

So it was that Azucena’s ayllu changed radically when she was still very young. Her parents decided to move to the city of Cochabamba to provide greater opportunities for their four children. Azucena studied to be a teacher, and when the pandemic arrived, at age 37 and already a mother, she wove together the two professions as her mother wove the ponchos and chuspas for her father when he was on the road. By day she was a schoolteacher, finding ways to pass the Andean values and the basics of plant medicine to the children of her Cochabamba classroom. And in her time off, she continued to help her parents in their medical practice and also to attend patients of her own.

When Covid came to Bolivia in March of 2020, the government quickly shut down the schools, and Azucena’s classes went online. She began orienting her students on the best ways to boost the immune system, and encouraged them to go out and exercise, to keep their spirits up, always keeping distance, but moving physically so as to not succumb to depression and then to the virus.

Abelino Paucar Pacheco, her father, began meeting with other Kallawaya doctors, and comparing notes about what was proving to be most effective both for preventing the contagion and then for treating the symptoms. Back in the Kallawaya territories, the healers were doing the same: focusing on prevention, on the one hand, and then pulling out the old time-honored medicines to treat the symptoms of the disease.

Time-honored immune boosters like onion, ginger and lemon were used to head off the infection – as well as a positive attitude. The healers began testing the medicines that worked best for treating the symptoms, as well. Eucalyptus, a powerful transplant to the Americas, was added to the vast traditional pharmacopeia that traveling Kallawayas had gathered from varied ecosystems throughout their communities: the frigid highlands, the temperate valleys and the steaming tropics all provided different medicines.

Soon her students and their parents began falling ill, and she was able to prepare herbal treatments for them that she would leave in little black bags near their homes, to avoid exposure. She would follow up with phone calls and coach them so they could prepare vaporizations, gargling solutions and warm herbal baths to calm the fevers.

Meanwhile Abelino was giving presentations at public fairs and markets, telling people how to prevent and heal from Covid with herbs. He began making a syrup with the plants that were proving effective at treating the symptoms, and began to attract patients who were desperately looking for a cure they couldn’t find anywhere else.

Crisis in the Cities

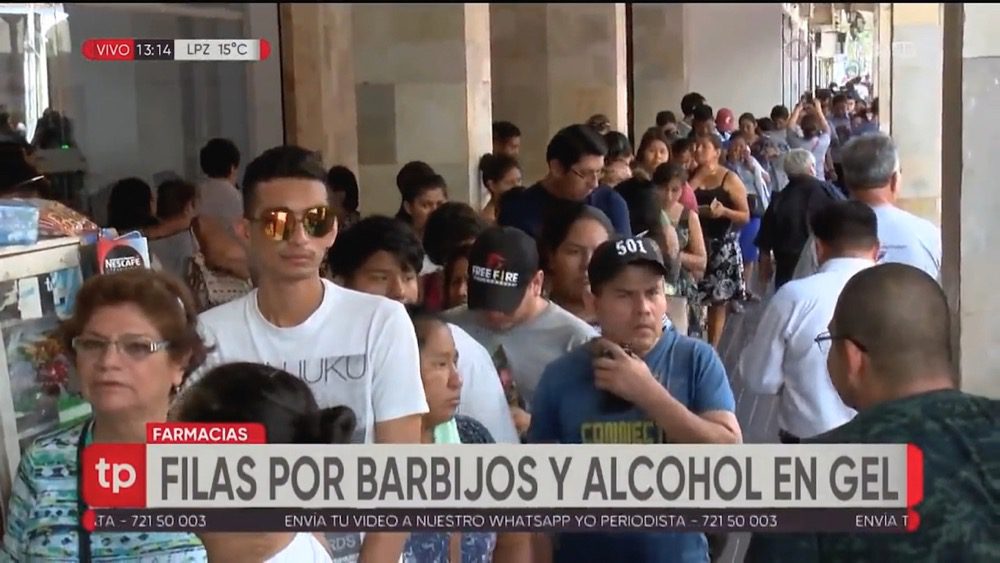

When the pandemic began, Bolivia was already in the midst of a political and economic crisis because of the 2019 takeover – considered a coup by many – of the right-wing government of the now-convicted Jeanine Añez. By the summer of 2020, hospitals were overwhelmed, and reports began coming out of people dying in the streets, unable to get treatment of any kind. The price of medicines and oxygen tanks skyrocketed and became unavailable to common people, so they could not even treat themselves at home.

Bolivia’s Forensic Investigations Institute announced in a statement that between April 1 and July 19 of 2020, more than 3,000 bodies that were recovered outside of hospital settings had been identified as either confirmed or suspected coronavirus cases.

People began lining up outside the homes of Kallawaya doctors like Abelino. Word had gotten out that he had cured five patients with his syrup, and soon the numbers began to grow.

“They came every night, and the line was immense,” said Azucena. The syrup had to be made fresh every day, so people returned daily for the treatment, which was later complemented with gargles and warm baths of medicinal herbs.

“We did the treatment from afar, at a distance,” commented Azucena. “In my family we have not fallen to the disease, thanks to God and the foresight and knowledge of my parents.”

Likewise in La Paz, the world’s highest capital city at more than 11,400 feet, people were lining up outside the home of Kallawaya traditional doctor Pedro Huaqui Silicuana, who had also migrated from his village of Amarete to the city so his children could go to school. Don Pedro was treating people with herbal teas and with his homemade herbal syrup. His daily routine began early in the morning, when he would load up his wheeled cart with different herbal solutions and make his way to the street market in El Alto, the majority Indigenous sector of La Paz. But during Covid, people were seeking him out at his home.

“They came to visit me, to see if their luck would be Covid or if it would be something else.” Depending on the symptoms he would make an educated guess, then treat them accordingly. “Many times, people don’t have Covid, it’s just fright. And so we began treating Covid, and my treatment was with (herbal) syrups that I prepared. Those who were cured spoke to their friends and told their neighbors. That is why people came to my house in La Paz, because I attended this and other illnesses successfully.”

As the pandemic unfolded, so did the political crisis. Another urban Kallawaya in La Paz, Lidia Patty Mullisaca, a former Bolivian congressional deputy-turned-activist, became involved in the effort to fight Covid, as well.

Mullisaca would later become known for her lawsuit against the leaders of the government takeover, accusing them of terrorism, which eventually put Añez and several of her ministers behind bars, convicted in Añez’ case of dereliction of duty and violation of the constitution. But in the early days of the pandemic, Mullisaca was putting her Kallawaya healing savvy to work.

Many people had begun to forget about traditional medicines, she said, turning instead to pharmaceuticals. But the lack of an effective government response to the illness opened the opportunity for the traditional ways.

“We would go to buy herbs but the doctor would give a pill for a son, for a daughter when she was sick. But we did not have that opportunity in the dictatorship… People lined up and it cost up to ten bolivianos ($1.50 USD) for a single pill. So, by necessity, we have recovered our medicinal plants.”

Mullisaca, who even in the city wears her traditional pollera skirt and red striped poncho, and typical Andean bowler hat with a handwoven wincha underneath, speaks earnestly.

We had no vaccines, no pills, not even aspirin. The government never brought them to the pharmacies… Well, by force we have recovered our medicinal plants.

Lidia Patty Mullisaca

Activist and former deputy

“I gave them out in the city, I passed them to the brothers and sisters,” said Mullisaca. “I gave to them prepared, tied bundles so they could heal, and Andrés Huaylla to bathe in, to lower the temperature.”

She also filmed a video showing how to make a healing tonic and published it on the web.

“Honey, then orange, then chamomile with eucalyptus, quinaquina (the tree from which quinine is made), then rosemary, coca, and after this, honey. We boiled those things, and with that I made a video, and that is why many people have been cured,” she explains. “They called me, they thanked me.”

Not everyone thanked Mullisaca for her labors. Then-Minister of Government Arturo Murillo, Añez’ right-hand man, lashed out at healers like her – perhaps even targeting Mullisaca herself – in a July 2020 press conference. “We have irresponsible politicians who, with lies and stories, get people out, telling them that this damn disease is an invention and is cured with wira wira,” he said. “It is not like that. It is cured with intelligence (…) it is not cured with stupidity.”

But after a strong citizen resistance, Bolivian voters overwhelmingly rejected the Añez government in the presidential election of October 2020, returning Evo Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party to power. Murillo, together with Añez, landed in jail. On Jan. 23, 2023, Murrillo was condemned to 70 months in prison in the US for blackmail and money laundering in the importation of tear gas from a US company. Meanwhile Añez, accused of orchestrating the coup that brought her to power, was sentenced to 10 years in prison by the Bolivian courts.

Kallawaya academic and traditional doctor Felipe Quilla, on the other hand, accepted a position with the Añez government as the vice-minister of traditional medicine. The position was short-lived as the administration soon eliminated the vice-ministry. But in the meantime, he witnessed a surprising phenomenon. In the face of a general failure of the nation’s health care systems, traditional medicine was being used everywhere – even in the wealthy neighborhoods of the nation’s capital.

They have been saved in the face of the Covid 19 pandemic, thanks to that ancestral wisdom that they still preserve. So that was essential.

Felipe Quilla

Academic and traditional doctor

“One fact that caught my attention was, for example, in the southern zone (of La Paz) – Obrajes, Calacoto, Achumani and Irpavi, where people with a lot of money supposedly live, they do not typically practice traditional medicine. But those families… also at home everyone had their chamomile, eucalyptus, wira wira, mate, their ginger with lemon.

“So, practically, Covid 19 has forced people to turn in the first instance to traditional medicine, to natural plants. Later, when there were already complications, they would go to the health center.”

In the rural areas, according to Quilla, the plant medicines saved untold numbers of lives.

“That happened in the Bolivian highlands, in the valleys, in the East, in all the original communities. They have been saved in the face of the Covid 19 pandemic, thanks to that ancestral wisdom that they still preserve. So that was essential. Otherwise, we might have had to mourn a lot more deaths, maybe a catastrophe. So, fortunately it did not come to that.”

In the Kallawaya Territories

Julian Vega, head of traditional medicine for his community in the Kallawaya municipality of Charazani, recalls his first reaction when he first began hearing about the pandemic on the news.

“In other countries, it was really serious; they were burying so many dead in bags, didn’t you see? So I thought to myself, first we doctors are going to die. So we have to prepare weapons. Let’s fight. Well, brothers, that’s why you have to prepare, you have to work. Doctors we are.”

Leaders throughout the Kallawaya territory organized themselves within their ayllus, according to fellow Kallawaya doctor Alipio Cuila Barrenoso. Traditional doctors, curanderos and elders met with the municipal and traditional authorities, sat down together and asked themselves, “How are we going to confront this evil?”

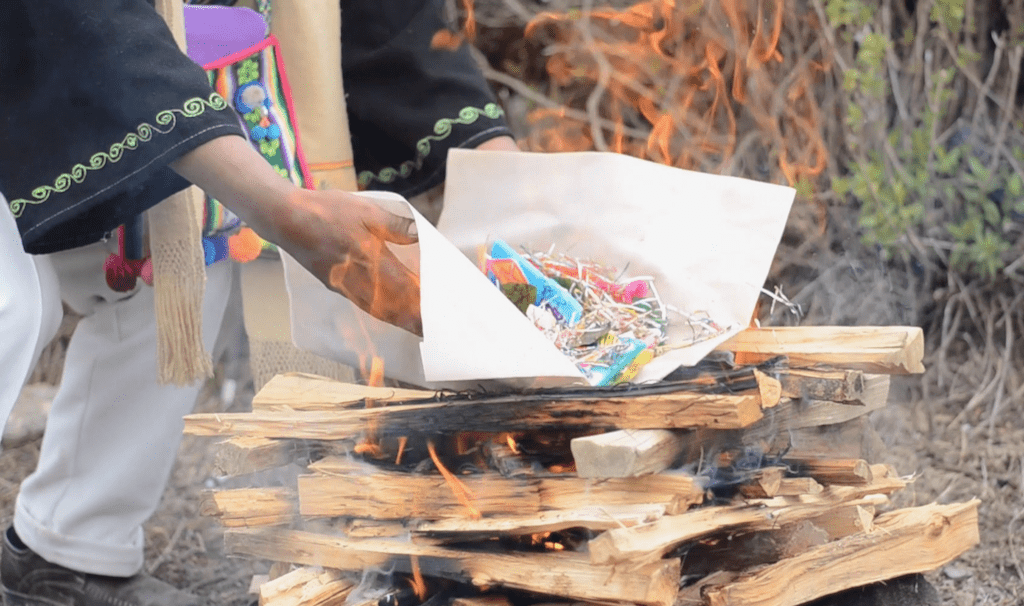

First of all came the spiritual work: requesting help from the holy mountains, where the spirits live who can help them. Before the pandemic arrived, they climbed up and asked for protection, leaving their offerings in the traditional way.

Frequent communication among the communities kept them apprised of the virus’ movement throughout the territory. They began to study the symptoms, thinking of previous epidemics that had had similar effects, and the medicines that had been used to cure them, and shared their results among each other.

And then, it was time to get to work.

“We couldn’t sleep, night and day… if we sleep, we waste time,” said Julian, who rose early to harvest herbs in the morning, and made his pomades and tonics in the evening, passing them out to those who came to his home, and then working in the hospital in the nearby town of Sotopata. He sent shipments of herbs to his contacts in La Paz, as well, and took them to distribute at fairs and public events.

The Kallawaya leaders approached the municipal government about funding a project to prepare traditional honey- and herb-based tonics aimed at helping people to strengthen their immune systems, and then to treat the symptoms when and if they came. The government supplied the materials, and the Kallawayas began harvesting.

They collected herbs from all different altitudes, from the highlands and the lowlands to the tropics; sweet plants and spicy plants; in short, they fabricated a syrup made of honey and the infusions of seven plants aimed at warding off any type of infection. Among them were antimicrobials like wira wira, a time-honored healing herb in the artemisia family; matico, or spiked pepper; and expectorants like eucalyptus.

“We made them as preventatives, but they ended up healing people, too,” said Alipio. They knew that the virus arrived first in the throat, and then moved to the lungs, and that was the point where the person would become seriously ill. So besides the syrup, they prepared an antimicrobial gargling solution to kill the virus before it entered the lungs. If that failed, the syrup contained an expectorant and herbs to calm the cough. They also made salves to help cool the body in case of high fevers.

Another project was a pamphlet with recipes for the syrup, the nectar and the salve. “We couldn’t really make enough products for everyone. So what could we do? We made recipe booklets, and then we traveled around the region, distributing them and giving talks.” They made three specific recipe collections for different regions, corresponding with the plants that grew nearby.

Something interesting happened when they traveled to different areas where people no longer practiced the traditions or remembered the medicines. “The people started remembering that, yes, this herb always worked. And they began to harvest, to gather everything that appeared in the recipe book… and then, arriving at their houses, they easily cured themselves.”

No studies have been done to confirm the efficacy of these plant medicines, but Alipio is one of many who believe that they are a big reason for the almost nonexistent Covid mortality in the Kallawaya territories.

The local diet is another reason frequently cited for the high resilience rate against the infection.

“When the pandemic got to us, everybody remembered what plants to gather,” said Roberta Quispe Mamani, an herbalist and midwife from Amarete. “We were almost not afraid here in the countryside. Here we eat our natural food; what we produce, potatoes, chuño, whatever. We produce with natural fertilizer, and nothing of chemicals. So in our food we have medicine, too.”

Another big difference, she said, is that unlike in the city, people don’t isolate their sick family members. “Here in the country we almost don’t isolate. Why not? Because the Kallawayas are like that. We don’t just look at each other and say, ‘oh, that one’s getting sick.’ We always know when someone is getting sick and we urgently go visit them. We can’t just look away when someone is sick with Coronavirus, can we?”

When her 80-year-old grandfather contracted the virus, she treated him with a variety of plants, including one commonly used throughout the region that they call guaco. The illness lingered, however, and she ended up treating him with a little-known traditional Kallawaya remedy: warm alpaca blood. Soon after, he rallied and healed.

Here we almost don’t isolate… We don’t just look at each other and say, ‘oh, that one’s getting sick.’ We always know when someone is getting sick and we urgently go visit them.

But Kallawayas are not just healers of the physical body. They attend to the whole spiritual dimension as well, trained in the rituals that must be done to provide ayni, reciprocity, to the deities who inhabit the holy mountains, the waters, the lightning and the Pachamama herself. According to Andean spirituality, these deities can exact a heavy toll on humans who do not practice ayni, making regular offerings to honor them.

This is where the ceremonial work of the Kallawayas comes in. Every Kallawaya carries his or her mesa, a sort of altar of medicinal herbs and sacred objects handed down through the generations: stones, crystals, shells, feathers, animal bones, symbols whose meanings only the Kallawaya knows. These objects serve as a channel to connect with the Pachamama, the apus and other beings, helping them to heal in the spiritual dimension.

Roberta remembers the times when there were tiemperos, people who controlled the weather. When it would get too dry, they’d go up to the mountain and ask for rain. When the rain was too much, they would ask for it to stop. Nowadays, said Roberta, with climate change – the rains don’t come when they are supposed to; frost covers the ground when it’s not supposed to, and the once abundant springs that would gush forth from the Earth are drying up, one by one.

“Now it seems that instead of man controlling the weather, it’s the other way around,” she said sadly.

Don Aurelio Ortiz, a well-known traditional doctor from the Kallawaya ayllu of Lunlaya, lamented the weakening of bonds between humans and nature. The rise of industry, factories and contamination plays a part in generating illnesses and will continue to do so, he says. “They make many illnesses appear, and they are going to keep appearing,” he said. He sees the ceremonial work as necessary to heal this rift, and is as much a part of wellness as the plant medicines.

“These illnesses, you could say concretely that they are related to bad energy, with what some call dark magic,” he said. “In these times, with these diseases, the people in the cities are fearful – and the fear is their weakness. We could say the person bewitches himself, no? He doesn’t leave his house, closes himself off, loses his self-esteem – and then the illness can act more easily.

When the human being distances himself from Mother Nature and from the apus, explains Aurelio, he loses a small part of his life. “It’s like losing his little soul. Then the Kallawaya makes his little soul return to the physical body, and that person is healthy and strong again. So the Kallawayas, we heal the soul.”

For more information:

Alderman, J. (2015). Mountains as actors in the Bolivian Andes: The interrelationship between politics and ritual in the Kallawaya ayllus. The Unfamiliar, 5(1-2). https://doi.org/10.2218/unfamiliar.v5i1-2.1217

White, grey and black Kallawaya healing rituals / Rösing, Ina. – Madrid : Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert, 2010 – 449 p. : col. ill. – ISBN: 9783964566393 – Permalink: http://digital.casalini.it/9783964566393

Janni, K.D., Bastien, J.W. Exotic botanicals in the Kallawaya pharmacopoeia. Econ Bot 58 (Suppl 1), S274–S279 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2004)58[S274:EBITKP]2.0.CO;2

Fernández Juárez, Gerardo. “Testimonio kallawaya : medicina y ritual en los Andes de Bolivia.” (1997). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abya_yala/289

Previous page Next page