BEAR BUTTE – About 100 people from all across the land gathered at this native sacred site Aug. 9 to pray and participate in the Sturgis Medicine Wheel Ride 2020 to raise awareness about the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Children and Two-Spirit relatives.

Native women motorcyclists led the 70-mile ride from Bear Butte, through the scene of the annual 10-day Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, to Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills.

Donning masks to protect from the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, they rode in support of the community nonprofits Red Ribbon Skirt Society and Where all Women are Honored, located in Rapid City. The motorcade ended with an art exhibit and benefit sales at the mountain carving of Crazy Horse.

As the Sturgis rally marked its 80th year, drawing hundreds of thousands of bikers to the area, organizers of the event also teamed up with three other civic groups in an unprecedented effort to help curb the nationwide problem of sex trafficking and violence.

They set up a booth attracting rally-goers to the “Fast Ride” program with an invitation to “come hear about what all is taking place around the country to combat trafficking. Hear from survivors that have been in the trade and escaped,” they said.

The invitation called for people to “come ride with the members of these organizations that are doing something about trafficking and find out how you can help.” It lists co-sponsors as Ride My Road, Fighting Against Trafficking, and The Epik Project.

State, county, and city law enforcement officers were on duty supporting the novel rides for the cause.

The events coincided with the release of findings and recommendations in a yearlong study to lay groundwork for all tribes to improve justice for victims and survivors.

Spearheaded by the Sovereign Bodies Institute in collaboration with members of the Yurok Tribal Court, located on the North Coast of California, the study is entitled To’ kee skuy’ soo ney-wo-chek’, which means “I Will See You Again In a Good Way,” according to Yurok language advisors.

The 146-page book is the first outgrowth of a project aiming “to generate a clear and thorough understanding of the scale and dynamics of cases of trafficked, missing, and murdered Native American women and children in Northwestern California.” It is part of a three-year endeavor to “design and implement a pilot blueprint for tribes to intervene in and prevent such cases,” it purports.

To accomplish this, the Yurok obtained a Coordinated Tribal Assistance Solicitation (CTAS) grant from the U.S. Department of Justice and contracted with Sovereign Bodies Institute, which is developing a nationwide directory of cases.

According to the authors, “Though each law enforcement agency may have documentation of such cases in each of their respective jurisdictions, no such information exists in an accessible, comprehensive cross-jurisdictional data set. Moreover, many agencies lack thorough information, as much of this violence goes unreported and undocumented, and can fall through gaps in communication and bureaucracy.”

Focusing on California’s largest tribe, the project identified gaps and collected facts on the violence, in the interest of empowering all tribes to enact effective, data-driven policies to address trafficking and MMIWG2 in their regions, according to participants.

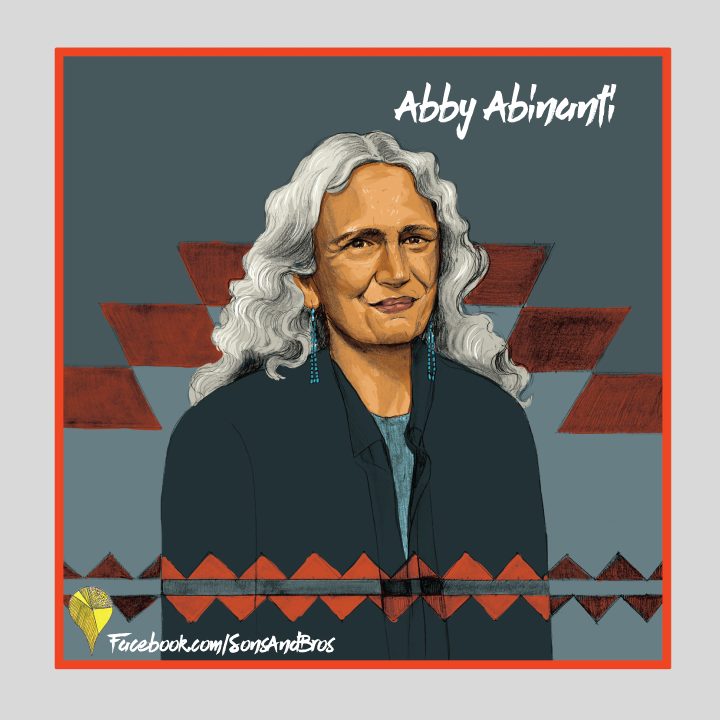

The key researchers are Yurok Chief Judge Abby Abinanti, award-winning sociologist and Yurok tribal member Blythe George, and Sovereign Bodies Institute founder and Executive Director Annita Lucchesi, a doctoral candidate in the Cultural, Social, and Political Thought Program at the University of Lethbridge, which is located on Treaty 7 Territory in southern Alberta Province, home to the Blackfoot Confederacy.

The Sovereign Bodies Institute calls itself “a home for generating new knowledge and understandings of how indigenous nations and communities are impacted by gender and sexual violence, and how they may continue to work towards healing and freedom from such violence.”

Abinanti bemoaned the “scarcity of accurate data on native MMIWG2 victims and survivors in California and everywhere else in the United States.” She said the databases that do exist “are largely inaccessible to tribes and are woefully inadequate when it comes to tribal populations.”

A former San Francisco Superior Court Judicial Officer, Abinanti explained that “parallel to the database component of this project, we are creating a cooperative plan that seeks to mobilize tribal, county, state and federal agencies in response to future MMIWG2 cases.”

Yurok Tribal Vice Chair Frankie Myers expressed high hopes for the project outcome, saying tribes “have the capacity to positively influence the resolution of MMIWG2 cases. I am confident that the collaborative approach called for in this report will facilitate real progress toward preventing future tragedies. We hope tribes across the U.S. will one day use this project as a model to achieve justice for victims, survivors and their families.”

Since the Gold Rush, tribes in California have lost countless women, girls and two-spirit individuals to violence. Most commonly, these crimes are perpetrated by non-Indians and away from tribal jurisdictions, the Yurok Tribe notes. The incidents impact every aspect of tribal communities, ranging from an increased need for services for survivors and their families to heightened strain on tribal law enforcement.

In addition to creating a comprehensive database, the tribe expects to introduce a formal protocol, integrating tribal, county, and federal law enforcement resources into the response to MMIWG2 cases. The report’s first recommendation is for local and federal law enforcement agencies to form cooperative agreements with their tribal counterparts.

The Yurok Tribal Police Department has cross-deputization agreements with the Humboldt and Del Norte County Sheriffs’ Offices, serving as an example of positive working relationships among law enforcement agencies. The agreements authorize Yurok officers to enforce all state laws.

The research also identified a need for state courts to strengthen relationships with tribal courts. Specifically, the report calls for an expansion of concurrent jurisdiction arrangements, such as the joint Family Wellness Courts led by Abinanti and the presiding judges of Del Norte and Humboldt counties.

In the report, Abinanti suggests that state courts institute a special, standard operating procedure for dependency cases involving foster children who have a missing or murdered parent. Court intervention will ensure that children receive the care they need when they need it most.

Tribal law enforcement, courts and attorneys can also assist in the successful investigation, as well as prosecution, of perpetrators and with connecting survivors with culturally appropriate services, the study finds.

Basing it on 165 Northern California cases, in which they interviewed affected family members and law enforcement officers, the researchers said their team hopes “that readers appreciate our intense effort to offer at least a sliver of the wealth of love, resilience, and perseverance that MMIWG2 families and survivors muster on a daily basis in their never-ending pursuits of justice.

“We hope that over the course of the many pages of this report, we have made it clear how loved missing and murdered women, girls, and two-spirit people are, that their humanity was both their source of their resilience and a component of their experiences as targets of violence. They were mothers, aunties, grandmothers, siblings, cousins, and so many more important roles, and they deeply counted in the lives of their loved ones. The absence after they are taken is a backdrop to their families’ lives forever.”

A Cheyenne descendant, Lucchesi reflected, “I am blown away by the strength and bravery demonstrated by all of the families and survivors that took part in this project. Our hope is that this report will bring healing to all of those who are impacted by MMIWG2 by bringing real change to societal and governmental institutions.”

It “is a call to action and a template for our communities. We know that innovation and resilience are skills within all indigenous communities, and it is those skills that will bring our relatives home,” she said.

Talli Nauman is a longtime Americas Program collaborator and columnist, a founder and co-director of Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness, and Health and Environment Editor for Native Sun News Today. She can be reached at talli.nauman(at)gmail.com.

A different version of this story ran in Native Sun News Today.

- Clemency for Lakota icon Leonard Peltier called ‘moral indictment’ - January 21, 2025

- Lakota tribes, grassroots close ranks to defend Black Hills watersheds - January 21, 2024

- Native ‘hempsters’ follow global cooperative example - August 30, 2023

Abby Abinati Black Hills Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls MMIWG Sturgis Motorcycle Rally Yurok Tribe