The gang came for “Sam” on his 15th birthday. He’d said “no” to them before. This time, they gave him an ultimatum: Join us or die. But poor though his family was, Sam did not want to enter a world of crime and brutality from which there was no escape.

The gang, born in Los Angeles and known throughout the Americas as Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13, doesn’t give third chances. The next time they came for Sam it was to run him over with a car.

They left him for dead. Remarkably, Sam pulled through. When he awoke three days later, with a head injury and badly bruised body, his mother pressed a wad of cash into his hand — about $30, maybe a little more. It was all she had in the world, plus what she was able to beg off friends. Like so many other Northern Triangle mothers, she faced a Sophie’s choice: unable to protect her boy from the cartel gangs, she had to kick him out of the nest. It was the only way to save his life…maybe. Along with the money, and through a veil of tears, she gave Sam one simple word of parental advice: “Run!”

Sam ran toward El Norte. He traveled on foot and by bus from Honduras through Guatemala, then rode the back of La Bestia, the perilous freight train, through Mexico to Texas. En route, he saw fellow migrants miss their step and get sucked between train and rails, their bodies shredded. He learned quickly how to identify and to steer clear of the gang members who preyed upon the migrants as they made their way north. He met teenaged girls, full with the children of their cartel rapists. He met other boys whose loved ones had been exterminated when they, like him, turned down MS-13 or Barrio 18 or Los Zetas. He met families of means back home who, robbed of every penny they’d painstakingly saved to pay a coyote to get them safely to The Promised Land, were reduced to riding the dangerous rails with him.

Young Sam ran toward the promise of a better life. He made it to the US border at Texas, where he tried to swim across the Rio Grande and nearly drowned. He was plucked from the swirling waters by members of one gang or another, but he managed to get away.

At Reynosa, Mexico, a recognized US port of entry, Sam walked across the bridge to the Customs Border & Protections (CBP) office at the northern end. There, he requested asylum. He was labeled a “UAC” — government-speak for an unaccompanied minor — and passed into the bureaucratic tangle that is the Office of Refugee Resettlement. ORR kept him in custody, locked up in a “shelter” — government-speak for an unregulated, off-limits detention center for kids — until his 18th birthday, when they could not legally hold him any longer. There, he received little education and was sexually abused by staff at the shelter in which he was incarcerated, as were a number of other kids.

A Lifetime Dedicated to Defending Human Rights

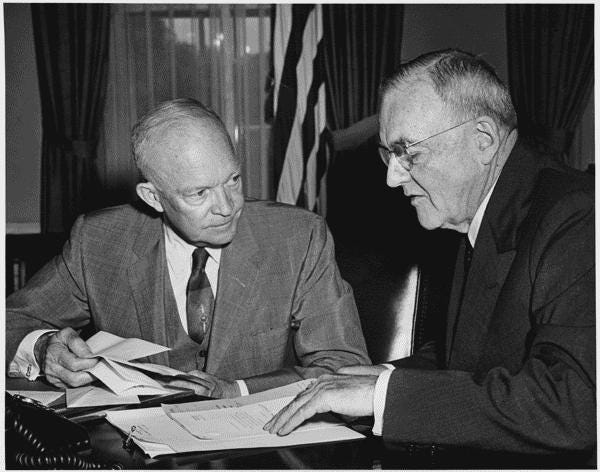

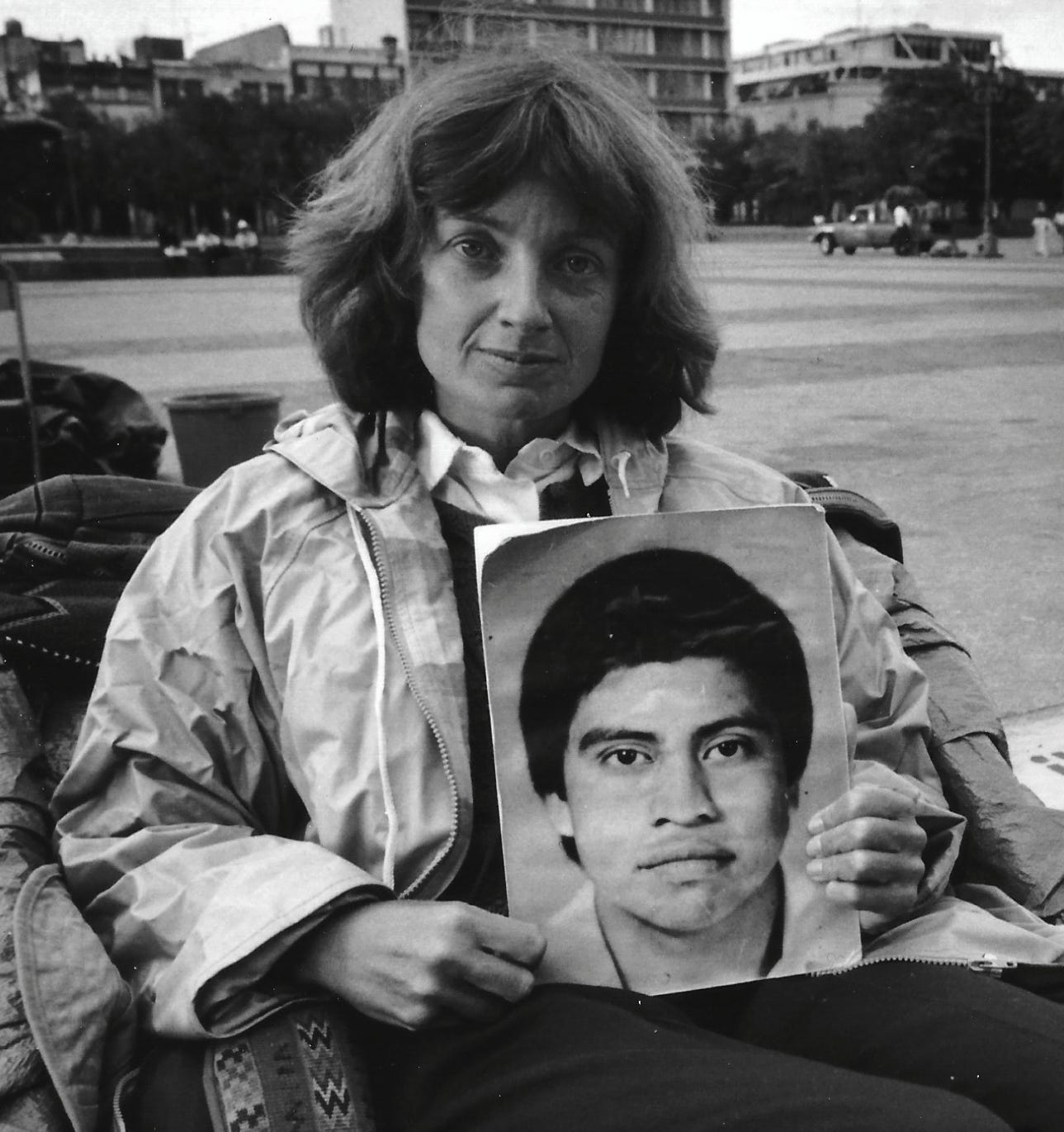

I heard about Sam’s journey from Jennifer Harbury, the attorney who handled the sexual abuse case to which he was a party. His isn’t the only horror story Jennifer has had to negotiate. A human rights activist, borderlands civil rights attorney, and author of Bridge of Courage, Searching for Everardo, and Truth, Torture, and the American Way, she has spent more than 40 years standing up to the USA’s habit of bullying and abusing its southern neighbors — a tragic reality that has gone largely unnoticed by too many until Trump & Co brought their unique brand of impunity to the US’s doorstep.

From her home in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley (RGV), Jennifer has been part of the humanitarian front against the Trump administration’s unnecessary and illegal border cruelty. She is currently working around the clock to get asylum seekers, who are innocent of any crime, freed from detention centers plagued by COVID-19, while also providing assistance to those stuck across the border in Reynosa. When then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy in April 2018, Jennifer was among the first to raise the alarm about CBP agents ripping kids out of the arms of their terrified parents. She was on hand to pass a secretly recorded audio file of children, despondent and crying for their disappeared parents, from whistleblower to the press — the same recording that woke the world and spawned a national movement to bring the heinous “family separation” policy to an end that June (at least on paper). She was also there when the take-a-ticket-and-wait-in-line migrant processing policy called “metering” reared its ugly head that same month.

One of the first to see the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” backed up, shoeless and parched, on the Reynosa-Hidalgo bridge — denied protection under international asylum law and baking under the relentless 100°F+ Tex/Mex sun — Jennifer immediately called for the help of friends, sparking the formation of the Angry Tías & Abuelas of the RGV.

“It was the most brutal thing I’ve ever seen,” Jennifer recounts, which is saying a lot, for Tía Jennifer has been witness to more inhumanity than most of the rest of us put together.

The Guatemalan Genocide

A privileged white girl from Connecticut, Jennifer never dreamed she’d one day expose the complicity of the US government and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the commission of war crimes when she graduated from Harvard Law School in 1978. That said, she did grow up with a fierce commitment to justice as well as a deep-seated belief in the democratic ideals of her birth nation — values instilled in her by her immigrant father. He had escaped war-torn Europe as a boy not much younger than Sam, also running from persecution.

Determined to focus on civil rights law, Jennifer took a job with a small legal aid organization in the Texas Panhandle, where she represented farm workers in employment and civil right cases. A few years later found her working with a legal aid organization in Florida. It was the early ’80s, the height of the Guatemalan genocide, and indigenous Mayans were streaming into the US. Few US citizens knew about it. And just as attorney Charlene D’Cruz witnessed at that time, from her post as a refugee advocate at the Florence Detention Center in the Arizona desert, Jennifer noted that US immigration officials were sending the terrified and traumatized right back where they came from, after forcing them to represent themselves in kangaroo courts without the help of translators with whom they might share their horrors.

She wanted to find out why these people were running, and what happened to them when they were returned. So she traveled to Guatemala in the mid-1980s. In 1990, she was cleared to venture into the jungle to meet with members of a guerrilla army formed to resist the brutal repression of the Guatemalan military and oligarchy. There, she met Comandante Everardo.

Born Efraín Bámaca Velásquez, he was a Mayan peasant who’d grown up hungry and barefoot and plagued by an unquenchable desire to learn. But his family needed him in the fields. He went to work as a boy, still younger than Jennifer’s dad was when he sailed across the Atlantic. Efraín couldn’t shake his longing for literacy, so on his 18th birthday he ran away. With the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG), he found a university under the trees. He was a voracious student and learned quickly, rising within the ranks to become a comandante, and one much loved by his troops.

Resist!

To understand why Everardo took up arms, we must time-travel to 1954, and a world in the thrall of a global contest between the US and the Soviet Union. That’s when the CIA orchestrated a covert military coup d’état to depose the democratically elected Guatemalan President, Jacobo Árbenz.

Ten years earlier, in 1944, a popular uprising toppled the repressive military dictatorship of Jorge Ubico. Guatemala’s first-ever democratic election followed, and Juan José Arévalo became the country’s first president. Making good on his campaign promise to bring democratic reforms to Guatemala, Arévalo set up a social security system, instituted a minimum wage, and redistributed land to landless peasants. Allowing for near-universal suffrage, he turned Guatemala into a democracy for the first time since its independence in 1839.

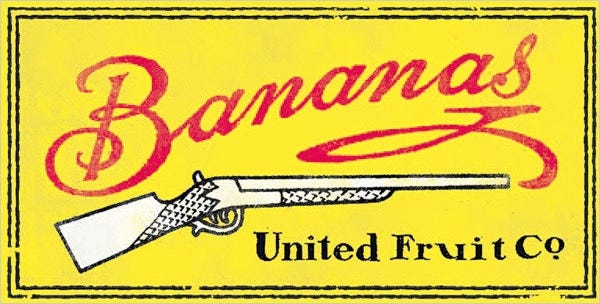

When Árbenz succeeded Arévalo in 1951, he built on his predecessor’s agenda. But even after buying lands claimed by the United Fruit Company (UFC) at full value, which he distributed to the poor, the US-based corporation notorious for its exploitative labor practices played the Cold War card.

The UFC had gotten used to profiting off the backs of poor Guatemalans so that US citizens could smoke cheap cigarettes, enjoy sugar on their cereal, and ensure their regularity with a daily banana. It screamed “communism!” so loudly the CIA got right to work, conceiving a plan to prop up US corporate interests rather than allow a sovereign nation to bring economic security its most vulnerable citizens.

The Unacknowledged History of US Imperialism

Upon toppling Árbenz in 1954, the CIA brought back to heel a nation previously tamed in the name of US capitalism. To understand that, we have to time-travel again, this time to the era of the “Banana Wars.”

Starting with the 1898 Spanish–American War and continuing into the 1930s, US military forces launched a series of occupations, police actions, and interventions throughout Central America and the Caribbean. Each event was branded and sold to the American people as an act of aggression necessitating a call to arms. In reality, they were carried out at the behest of US banks and big business, particularly the UFC, which had significant financial stakes in the production of bananas, tobacco, sugar cane, and other products throughout the region.

In addition, the US government had its eye on Panama. If the US could obtain control of the isthmus, into which it might carve a deep canal, linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, it could exert total control over the Americas and dominate worldwide economic trade and geopolitics.

One of the top enforcers of the Banana War strategy eventually saw through it, blowing the whistle on these “dirty wars.” In 1935, the exquisitely named Major General Smedley Darlington Butler, a senior US Marine Corps officer, penned a book called War Is a Racket in which he outed the US as an imperialist aggressor that had misappropriated its armed forces to work as “gangsters for capitalism.” For the 33 years and four months that “Old Gimlet Eye,” as he was known to “the boys,” was in active military duty on three continents, he was, in his words, “a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers.”

He made Mexico “safe for American oil;” Haiti and Cuba “a decent place for the National City Bank boys.” He helped “rape half a dozen Central American republics,” including Nicaragua, which he “purified” for Wall Street. He “brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar;” and he “helped make Honduras right for the American fruit.”

The Banana Wars ended with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1934 Good Neighbor Policy. He repudiated US interference in the domestic affairs of its southern neighbors, advocating instead that they be left alone to develop their own economies and governments. Reciprocal trade with the US would follow — a win for all. This is indeed what happened in Guatemala, for a time, giving rise to the democratic elections of Arévalo and Árbenz.

Love in the Time of Impunity

But the Good Neighbor Policy was relegated to el dompe of history when the CIA overthrew the Árbenz government in 1954. The military dictatorship the US installed promptly took back the lands distributed to the Guatemalan poor, returning them to the UFC. Voting rights were snatched away as well.

Having tasted the sweet fruits of social justice and political participation, Guatemalans found renewed disenfranchisement and still-remembered oppression too bitter to swallow. The first wave of civilian fighters took up arms in 1960.

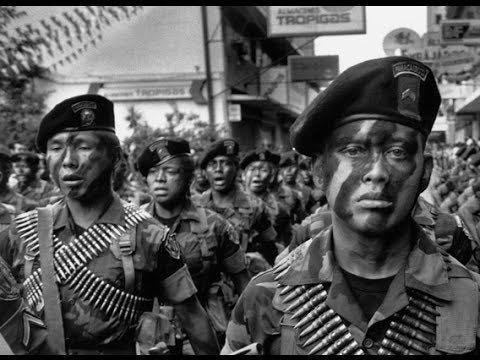

The 36-year civil war that ensued was marked by abductions, torture, and disappearances; the dumping of bodies scarred by violent mutilations in public places; and the strafing, bombing, and burning to the ground of remote villages. The more brutality the military got away with, the more brutal it became, leading to a culture of impunity in Guatemala that targeted, above all, the indigenous and spared none among them: not women, children, nor the elderly.

It is within this context that Jennifer Harbury stepped into the hidden jungle encampment of the Mayan Resistance group led by Comandante Everardo. At first, Jennifer took the baby-faced soldier to be a much younger man. But when he spoke, she recognized a person wise beyond his 33 years. The two felt the spark of a connection they knew could not be: Everardo belonged in the mountains with his battalion; Jennifer was needed at the front lines of the civil rights battles waging in the US. But the two corresponded. And in handwritten letters that read like poetry, Everardo confessed his love for Jennifer, which she reciprocated.

In 1991, they were wed. In 1992, not quite a year later, Everardo was captured by Guatemalan military forces. They faked his death, then disappeared him so that they might torture him for information, which they did, possibly for as much as three years (accounts vary).

The Truth Will Out

We might never have learned the truth of Everardo’s fate if it weren’t for Jennifer’s love of both man and justice — as well as her profound knowledge of international law. In her search for Everardo, which included a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the CIA and three hunger strikes — one in front of the White House — Jennifer exposed US complicity not only in the extended torture an death of her husband but in the Guatemalan genocide.

What’s more, her quest for justice for Everardo led to an historic judgment issued by the Inter-American Human Rights Court, which set new regional standards with regard to truth, justice, and reparations in the context of the Dirty Wars that devastated Central America throughout the 1980s and ’90s. For Guatemala was not unique: Nicaragua and El Salvador also tried to get out from under Washington’s knee at that time, with tragic results, while the Soto Cano (aka Palmerola) Air Base in Honduras became the staging ground for US-backed and trained paramilitary armies ordered to keep the region safe for the UFC, and its like. Even today, impunity is alive and well in Guatemala and the region, according to the Inter-American Court.

I lived and worked in the Northern Triangle throughout the years of Jennifer’s search for truth. I never imagined our paths would cross, and I did not at first recognize Tía Jennifer as the celebrated lawyer who cracked the thin veneer of what we internationalistas then knew: the US government in the 1980s wasn’t protecting us from communism at all. It was protecting capitalism from the barefoot mothers and illiterate fathers who longed for the dignity of feeding their malnourished children.

Thanks to Jennifer, we now know that the men involved in torturing Everardo to death, like Colonel Julio Roberto Alpirez, studied at the School of the Americas, trained at North Carolina’s Fort Bragg, and were paid handsomely by the CIA for information extracted through the cruelest of practices. We know their targets were not just guerrilla fighters, but also union leaders, activists, students, teachers, and religious leaders, among them US citizens, such as Father James Carney, Sister Dianna Ortiz, and Michael DeVine.

All so we in the US could sprinkle sugar over our cereal topped with sliced bananas and chased down with a cup of coffee.

Trapped!

The US-sponsored Dirty Wars saw the military slaughter of an estimated 30,000 Nicaraguas; 75,000 El Salvadorans, with untold numbers more disappeared; and 200,000 Guatemalans, 83% of whom were Mayan. They also created some of the most barbaric killers history has ever known: people transformed into monsters, who for decades were given free rein to torture, mutilate, rape, recruit child soldiers, and carry out village to village massacres with impunity. They committed some of the most egregious human rights violations under the eye — and under the cover — of the US CIA. They are protected by the CIA still.

When the Dirty Wars ended and the truth of Everardo’s death came to light, President Bill Clinton apologized and the US military largely packed up and went home. It still uses Soto Cano as a launching point for disaster relief and humanitarian aid missions. But when it left, it left behind a region awash in armaments as well as a generation of now-unemployed officers who had amassed personal fortunes as CIA informants and knew only one skill: how to bend people to their will.

Overnight, these thugs, whose hearts had long ago been destroyed, morphed from highly paid CIA assets into drug lords. Then, in a truly twisted and myopic move, US law enforcement rounded up members of the Los Angeles MS-13 and Barrio 18 gangs and, instead of throwing them in jail and destroying the key, deported them. This is how the US government came to supply the drug lords it created with their own personal armies.

“We should be going after them,” states Jennifer. “Instead, Trump & Co are punishing their victims.”

People like Sam will keep roaring north until the US acknowledges and addresses the true cause of ongoing Central American immigration: with the Frankensteins it created who now rule the region with such impunity, the notion of “government” is elusive. Indeed, they even own the police.

Meanwhile, from Banana Wars to Dirty Wars to Drug Wars, we’re all trapped in a vicious situation that was 100% Made in the USA.

Epilogue: Asylum’s End = The End, for Many

The day Jim and I set off from Brownsville to McAllen, striking out on our intended westward journey along the border to El Paso, 30-something-year-old Jesús García Serna entered the CBP office on the Reynosa-Pharr bridge and requested asylum. He insisted that his life was at risk; that he was hunted by criminal gangs. He pleaded that if sent back to Mexico, he would be tortured and killed. At about 5pm on January 8, 2020, Jesús left the CBP office. His insistence that he be allowed to pursue asylum in the US, as per international law, had been flatly denied.

He started to make his way across the bridge, but just a few feet past the international boundary on the Mexican side, he thought better of it. He stopped. He drew a knife from a pocket, reached up to his neck, and slit his own throat. By the time CBP agents reached him, he was dead, lying in a pool of his own blood.

And Sam? Lovely, intelligent, resilient, resourceful Sam? Sadly, the multiple traumas — of near-death experience at the hands of the cartels, his terrifying journey northward, and the years of abusive captivity in the ORR “system of care” — broke him.

“He simply couldn’t make it on the outside,” Jennifer told me.

Sam — a fictitious name for a factual young man whose potential has been squandered by the US now hundreds of thousands of times — was found dead from a drug overdose, killed by the very evil he’d fled MS-13, and Honduras, to escape.

Sarah Towle is an award-winning London-based US expatriate author sharing her journey from outrage to activism one story of humanity and heroism at a time. You may recall her stories on the Angry Tías and Abuelas and Redneck Revolutionary Brendon Tucker as well as her Action Alert on the terrifying Sophie’s Choice facing asylum seeking parents in detention. This is Episode 13 in her travelogue of a road trip gone awry: THE FIRST SOLUTION: Tales of Humanity and Heroism from Trump’s Manufactured Border Crisis, rolling out on Medium as fast as she can write it — because, in Sarah’s words, “it’s Just. That. Urgent.”

border policy Dirty Wars family separation immigration Jacob Arbenz Jennifer Harbury Mara Salvatrucha School of the Americas United Fruit Company

Excellent essay It deeply moved me and I will try to share it with USA citizens