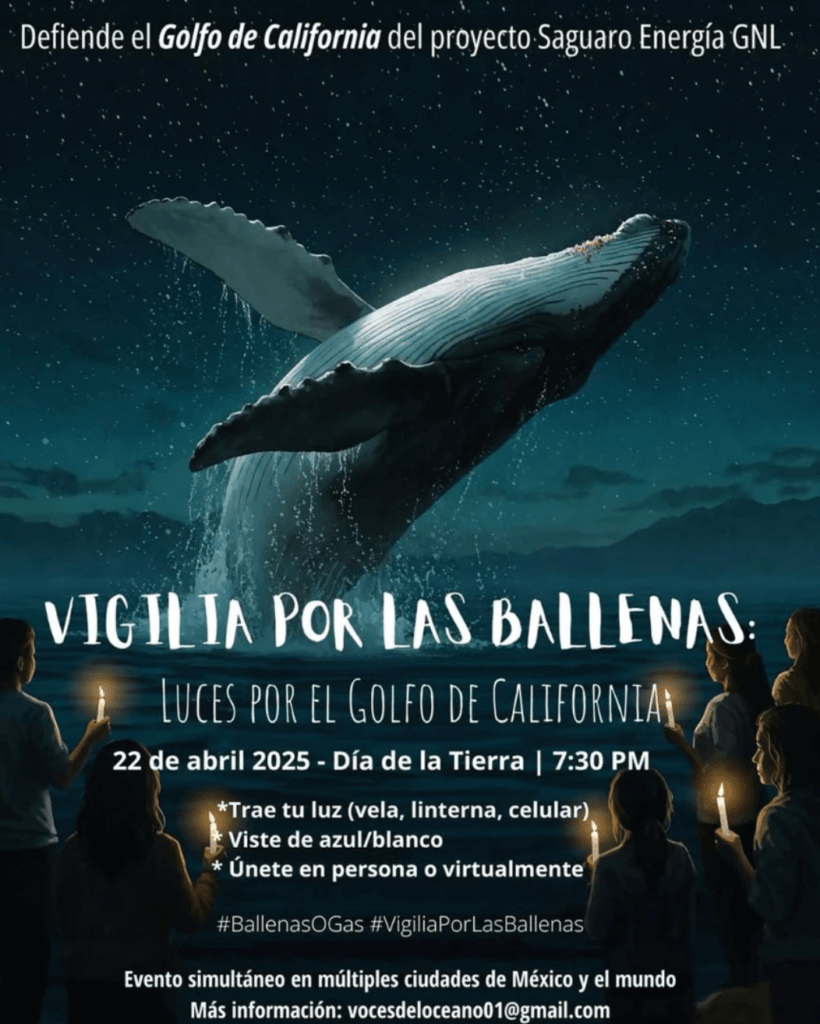

On April 22 — Earth Day — communities across Mexico and beyond will rise in defense of one of the world’s richest marine ecosystems: the Gulf of California. Artists, scientists, local fishers, and activists will gather in coastal towns and cities to say no to the Saguaro LNG project, a transnational gas export plan that threatens endangered whales, fragile coastal communities, and the global climate.

At the heart of this movement is Beatriz Padilla, a 62-year-old artist who is staging a 21-day hunger strike and live painting protest in Loreto, Baja California Sur — one of the areas most at risk.

Leer este artículo en español aquí.

“I couldn’t sit this one out,” says Padilla. “When I heard about what was happening here, I said, Not on my watch.”

Often called “the world’s aquarium” by Jacques Cousteau, the Sea of Cortez — or Gulf of California — is one of the most biodiverse marine ecosystems on Earth. This narrow body of water harbors over 900 species of fish and more than 30 species of marine mammals, including blue whales, sperm whales, and the critically endangered vaquita marina.

It’s a vital breeding and feeding ground for migratory cetaceans and a sanctuary for countless endemic species found nowhere else. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Gulf sustains not only marine life, but also the coastal communities who depend on its fragile balance for food, culture, and ecotourism.

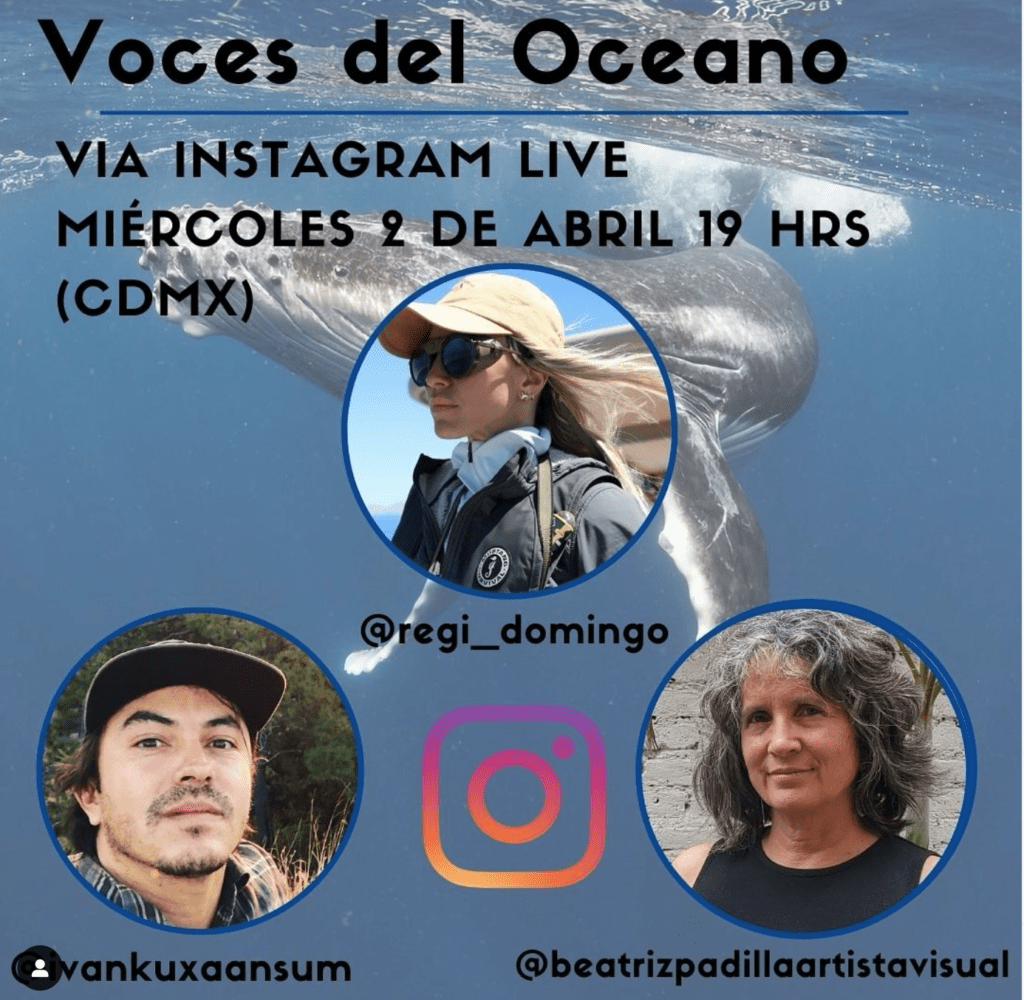

Regi Domingo, expedition wildlife leader and founder of the Nakawe Project, echoes the alarm: “This is not just a threat — it’s an assassination,” she told Voices of Amerikua founder Ivan Sawyer García in a recent Instagram Live. “Not just of a single species, but of migratory species and of the communities that depend on them.”

Padilla is calling her campaign Voces del Océano — Voices of the Ocean — and she’s inviting others to join her, both in person and online, in making April 22 a turning point.

Supporters are encouraged to:

- Join or organize local rallies, performances, or social media actions using the hashtag #BallenasOGas (Whales or Gas)

- Share and sign the Avaaz petition calling on President Claudia Sheinbaum and SEMARNAT to halt the project

- Follow and amplify Padilla’s updates via Instagram (@beatrizpadilla.artistavisual) and Voices of the Ocean livestreams

- Write directly to international oversight bodies such as UNESCO, CITES, and the International Whaling Commission

“With enough eyes on this, we can stop it,” she says. “But it has to happen now.”

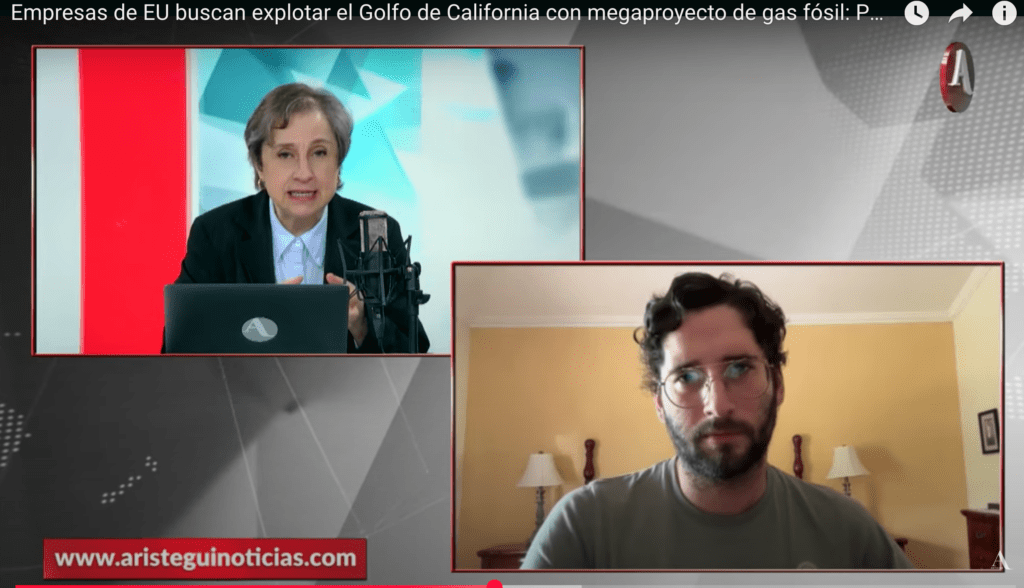

A Foreign Gas Project, a National and International Sacrifice

The Saguaro Energía project, led by U.S.-based Mexico Pacific Limited, would pipe fracked gas from Texas through an 800-kilometer pipeline across northern Mexico to a liquefaction plant in Puerto Libertad, Sonora. From there, the gas would be exported via giant LNG tankers to markets in Asia. The project’s proposed shipping route slices directly through sensitive whale habitat, including the Bahía de los Ángeles Biosphere Reserve — one of the most important aggregation zones for cetaceans in the region.

“There’s no remediation possible where you can convince a whale to coexist with a roar that prevents it from communicating for all of its vital functions,” said Pablo Montaño, director of Conexiones Climáticas, one of more than 30 organizations that have filed complaints with United Nations bodies, interviewed by journalist Carmen Aristegui on April 17.

Indeed, scientific studies show that underwater noise pollution from ships and construction can cause permanent hearing damage to marine mammals, disrupt migration and mating patterns, and in some cases lead to mass strandings. The Saguaro project would bring year-round shipping traffic and infrastructure development to an area that has remained relatively untouched — until now.

Even more concerning, say environmental groups, is that the project offers no benefit to the Mexican public. As Montaño explained, “This gas is fracked in Texas, transported through Mexico, and exported to Asia. The only thing Mexico gets is the environmental damage.”

Voices from the Frontlines: “It’s Not Just About the Whales”

While Beatriz paints on the shores of Loreto, others like Regi and marine biologist Juan José “Juanjo” Palafox are sounding the alarm from the sea itself.

Domingo, a marine conservationist and eco-tourism guide who has spent over a decade documenting whale migrations in the Gulf of California, described the region as one of the last pristine marine ecosystems on Earth.

“It’s a refuge — A place where whales come to feed, sometimes to reproduce, sometimes to give birth. It’s a loyal, annual destination during the winter feeding season.”

That silence is precisely what’s at risk. The Saguaro project would bring massive tankers and construction noise to an area already under strain from climate disruption. These sounds don’t just disturb marine life — they can injure or disorient whales, who depend on echolocation to navigate, feed, and communicate.

“They’re incredibly sensitive,” Domingo explains. “We have to turn off the motors and drift just to observe them. Now imagine what an industrial port and shipping corridor will do.”

Palafox, a marine biologist and photographer based in La Paz, emphasizes the broader ecological stakes.

“The Gulf of California is known as the Aquarium of the World for a reason. Here we find around 12,000 species — plants, marine mammals, fish, corals, invertebrates… a great diversity of life that, as we know, each plays an important role in ecological balance.”

Palafox said the project would unleash a cascading set of impacts — from fracking and methane emissions to noise pollution and disrupted migration patterns — that together threaten to unravel the delicate balance of life in the Gulf. “The damage is irreversible,” he warned, “not only to whales, but to the entire marine web.”

Both Domingo and Palafox point to a critical economic contradiction: while the project promises short-term jobs in Puerto Libertad, it threatens long-term livelihoods across Baja and Sonora that depend on fishing and tourism — industries rooted in a healthy marine ecosystem.

The sea supports the food systems as well as the tourism economy of the arid coastal region, where cultivation is difficult, said Domingo. “The sea is everything. It’s where there is culture, where there is history, where there is identity.”

Lighting the Way for the Whales

In cities across Mexico, communities are preparing to mark Earth Day with a message of resistance. At the heart of the action is a nationwide vigil — Velada por las Ballenas — organized by grassroots networks like Direct Action México and Whale Shark Mexico, with support from a growing alliance called Ballenas o Gas.

“We’ll be lighting candles in the shape of a whale,” said Andrea Michelle Gaytán Larrea of Whale Shark, a marine researcher with Whale Shark Mexico in La Paz. “To show that people care — that the ocean has defenders.”

In Mexico City, Gaby from Direct Action Everywhere – México City (dxecdmx) is helping lead the gathering outside the Palacio de Bellas Artes. “The oceans are our lungs,” she said. “And we have to defend them.”

For Iván Sawyer García of Voices of Amerikua, who convened the series of livestreams connecting organizers across the country, the vigils are just the beginning. “This is about building awareness and collective power,” he said. “So that people in every part of the country understand what’s at stake — and rise up to protect it.”

To follow and support Beatriz: https://beatrizpadilla.org/vocesdeloceanoenglish.html

To follow Iván’s entire series: https://www.instagram.com/ivankuxansum

To sign the petition: https://secure.avaaz.org/community_petitions/es/claudia_sheinbaum_y_joe_biden_las_ballenas_de_mexico_estan_en_grave_peligro/

To find or organize a vigil near you: https://shorturl.at/xTA9L

Join the campaign BallenasoGas (Whales or Gas): https://ballenasogas.org