Yesterday, in an explosion of celebration, dance, music and pure love, the Peace and Dignity Journeys runners from the North — the Route of the Eagle — met their counterparts from the Route of the Condor. It was a long-awaited encounter south of Bogotá, Colombia, with runners that started their journey in Alaska in May, while another group set off at the same time from Patagonia. We caught up with Route of the Eagle runners during their pass through Guadalajara. Today we celebrate with them and share this story in their honor.

The haunting call of conch shells pierced the afternoon air in downtown Guadalajara’s Plaza de Fundadores, where the statue of Francisco Tenamaxtli — the Americas’ first documented human rights defender — stands witness to centuries of indigenous resistance and resilience. As the runners of the 2024 Peace and Dignity Journeys emerged into the plaza, their staffs adorned with feathers and carved animal totems, they were greeted by local dancers and the ancient rhythms of drums and teponaztli.

Para leer esta historia en Español ir a Senderos Antiguos, Oraciones Modernas: Las Caminatas de Paz y Dignidad 2024

These runners had been on the road since May, part of an extraordinary continental prayer that began simultaneously at opposite ends of the Americas. While they ran south from Alaska, another group was running north from Patagonia. Now, as November draws to a close, both groups are approaching their final destination in Silvania, Colombia — a historic convergence that embodies an ancient prophecy of the Eagle of the North joining with the Condor of the South.

“These running journeys we’re making, this is the most ancient way of praying,” one runner explained during the welcoming ceremony. “This isn’t about resistance to colonization — this is a continuation of what our people were already doing.”

From Alaska South: The Runners’ Journey

“I live on the run right now. I have no house. I quit my job,” said Shawnz, a Native Hawaiian who was living in Phoenix when she heard about the Peace and Dignity Journeys. “I packed everything. I have no car. I’m literally on the run.” Starting from Alaska in May, she witnessed firsthand how similar prayers echoed across indigenous communities from north to south.

“Every community prays for the same thing — for water, for land, for missing and murdered indigenous women, for the kids, for addiction,” she reflected. “It makes you realize how we’re all connected, how we’re all related.”

“We are just the feet of the staffs,” explained Angel Retana, a Yoreme from Sinaloa who left his psychology practice to dedicate himself to ceremony. The meaning of his indigenous name, Witimea, is “he who kills while running” — preserved from ancient times when his people successfully resisted conquest. This was his sixth journey since 2000.

“What the runner receives for their offering is immense,” he said, “because what the runner puts as an offering is their life.”

For Raudel Mesa from the Kumiai community of Juntas de Nejí in Tecate, the journey brought unexpected healing. A lifelong asthma sufferer, he found himself able to run without medication. “This is not about the running,” he explained, “but about the prayer, the staffs, and God.” His participation carried a specific intention from his community — a prayer for maintaining indigenous languages and reuniting families separated by borders.

The Long Road South

From Alaska through the Yukon, Canada, Washington, Oregon, and California, the runners had traversed landscapes of startling beauty and solitude. Their route followed ancient pathways that, as one runner noted, “Google Maps doesn’t show.”

“Running through Alaska, Canada, just up north in First Nations — it’s just you with nature,” Shawnz recalled. “The mountains, the snow, the animals, the bears, the moose… No traffic. Not that many people. It’s just you and nature… You’re so connected with the Creator, the Earth, just everything.”

They crossed the Sonoran Desert in the intense summer heat, where Kumiai runners helped them navigate the vast Laguna Salada. Through Mexico and Central America, they were received by communities in ways both humble and grand. San Juan de Ocotán welcomed them with traditional Tastuane dancers, conch shells, and ceremony. “In all the communities we’ve arrived at, they receive us, there are committees that give us welcome,” Raudel explained, “but none like this.”

The runners described how borders and boundaries seemed to dissolve as they moved south. “When you cross frontiers or regions, you distinguish this mosaic,” one runner shared. “They are the Nahuas, the Aztecas, Zapotecas, Mayas, and then after the Maya fringe you find family in El Salvador who receive you with joy and you feel at home. And why? Because they also have Nahua roots.”

As Claudia, one of the runners, held her staff with reverence that August afternoon in Guadalajara, she spoke of an experience that defied ordinary description. “Being the carrier of these staffs, these grandparents… the welcome we receive in each place we visit is something that sometimes cannot be described in words,” she shared. “It’s a feeling you carry, emotions that move in beautiful ways. Each staff carries a prayer, an intention.”

These staffs, or bastones, are far more than decorated wooden poles. They are living entities that choose their carriers, maintain their own sacred intentions, and gather prayers from each community they pass through. Some have been running these routes since the first Peace and Dignity Journey in 1992. Others are new, born from the specific prayers of communities along the way — prayers for water, for women, for healing, for the preservation of language and culture, for the reunification of families separated by borders.

The Vision Takes Root: 1990-1992

“When a student is ready, the teacher appears,” reflected Delia, one of the original participants. Delia was one of the elders who gathered in mid-August for a círculo de palabra or talking circle, an ancient Indigenous tradition, at the Tloke Nawake Cultural Center in Guadalajara. There a group of veteran runners shared with these current runners how the Peace and Dignity Journeys first began.

She described how in the mid-1980s, a growing consciousness was emerging among indigenous peoples and their allies. “We began to question why we spoke Spanish if we were Mexican. We began to question why we had such a European way of life when we lived in a different continent.”

The story of how the continental runs began takes us back to 1990, when three visionaries — Alfonso Pérez Espíndola, Aurelio Díaz Tezpancali, and Francisco Melo — gathered with elders from across the Americas in Quito, Ecuador. There, they conceived of a peaceful manifestation that would demonstrate the ongoing vitality of indigenous traditions, choosing to respond to the upcoming quincentennial of Columbus’s arrival not with protest but with prayer.

“The whole world had their eyes on Teotihuacán,” recalls Coyote Negro, describing the convergence of the first run in October 1992. “Thousands came — a world of people from Canada, another world of people from the United States, and people from northern Mexico, from all the ethnic groups.” In those days, he explains, there was no institutional support — just the will of the people, the heart of each little town they passed through.

A crucial moment came when they began speaking to communities not just about peace and dignity, but about honoring the grandmothers and grandfathers. “That’s when the pueblos opened up,” one veteran runner recalls. “That’s when we touched that deep feeling of respect that still exists in the pueblos. After that, they wouldn’t let us leave — ‘Keep dancing, keep singing, come back.'”

Dreams and Prophecies: The Journey Continues

Since that first historic convergence in 1992, the journeys have continued every four years, each with its own focus — for children, for women, for ancestors, for sacred sites, for water, for native seeds, for sacred fires. The movement grew beyond what its founders had imagined, spreading to other continents.

A particularly powerful moment came in 2012 at Uaxactún, Guatemala. There, the 21 Maya pueblos gathered to receive the runners, their council of elders requesting that the Quetzal bird join the Eagle and Condor in the journey’s symbolism. The ceremony took place in Lake Itzá, where the staffs were bound together in recognition of this expanded unity — a gesture that further wove together the prophecies and spiritual traditions of North, Central, and South America.

“We are the prophecy,” the veteran runners emphasized. As one elder explained: “Through various generations, they left us the bases, they left us the knowledge, they left us the sacred circle, the drum, our lodge where we could come to pacify the things of the mind and heart, to continue conserving the greatness of what we are.”

The traditional four-year cycle was interrupted in 2020 when the pandemic closed borders across the Americas. But as the veteran runners share, this eight-year pause has only made the 2024 journey more significant. “In these times,” one elder reflects, “we must be united to achieve the dream of that hope, of those changes, where true civilizations will be forged — with more freedom, more responsibility, where life is savored, not just survived.”

A Sacred Moment in the Rain

As the runners approach their historic convergence in Colombia, perhaps Pavel Félix Ortega from Culiacán best captures the transcendent nature of their journey. Running alone in the rain, he experienced a moment he says he would choose as his favorite day of life if asked at the moment of his death.

“I wanted to capture it all in my memory,” he recalls. “I started describing it out loud as I ran — no humans, no technology, no cars, just the grey of the sky, the green of the mountains, the black of the road. I felt I didn’t have the capacity to measure the magnitude of what was happening.”

This sense of connecting to something beyond ordinary understanding echoes through all the runners’ experiences. As Claudia Valenzuela Martinez explains: “Even though I’m mestiza, when you’re running, you remember that you too carry ancestral roots, that there is medicine within. We’re doing this work for the awakening of humanity as beings of love, beings of health, beings of the stars, beings of the earth.”

Now, as these prayer-runners prepare to meet their counterparts from the south, they carry with them not only their sacred staffs but the accumulated hopes, prayers and dreams of hundreds of communities along their path. In their footsteps, they fulfill prophecies and visions that stretch back generations, demonstrating that the ancient routes of connection across the Americas remain alive and vital, ready to serve the next seven generations to come.

You can follow Shawnz’s journey on her Facebook page, and the Route of the Eagle group on José Malvido’s page, among others. The Route of the Condor group from the South has their own page. Learn more and donate HERE.

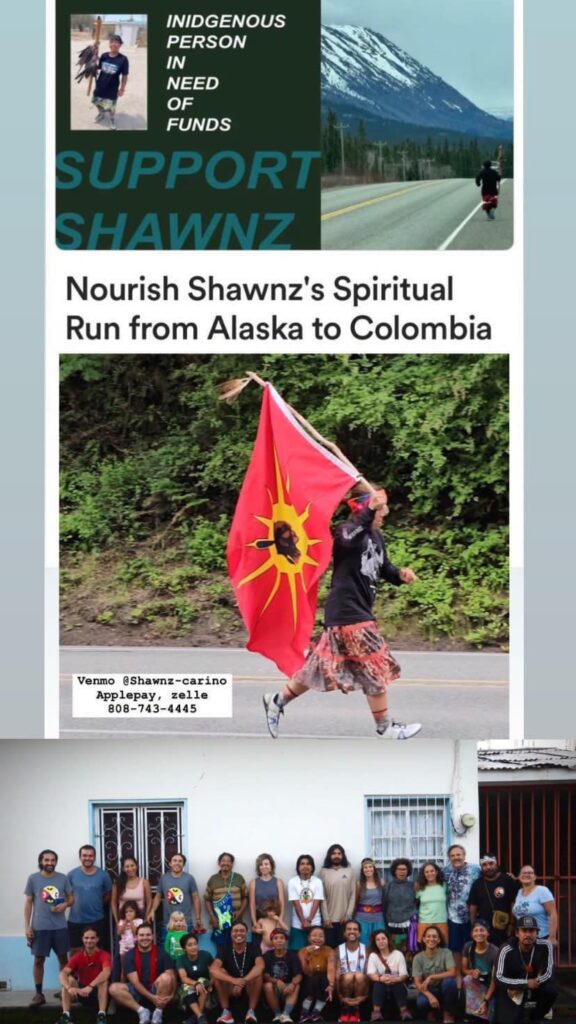

Shawnz, the Native Hawaiian runner who most touched my heart, has her own fundraiser and will need support as she reintegrates into a new life after six months on the road. You can support her at Venmo @Shawnz-carino, Applepay or Zelle at +808-743-4445.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

Jose Malvido Peace and Dignity Journeys 2024 Plaza de Fundadores Guadalajara