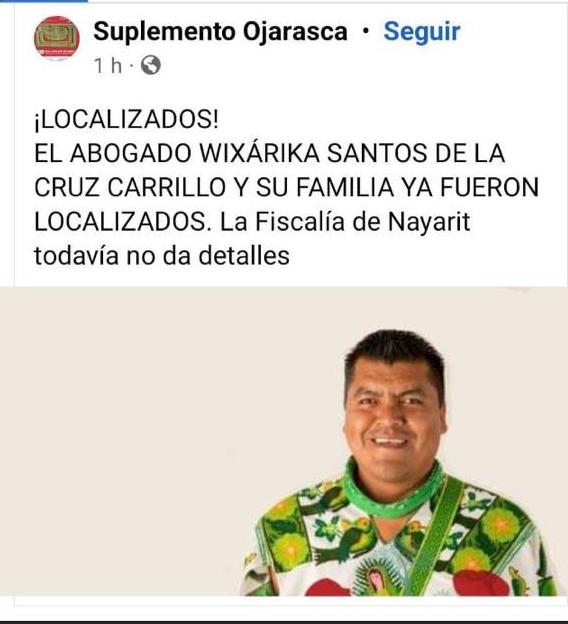

This weekend has been a frightening one for many here in Mexico — at least among the people who care about the land and our Indigenous peoples. The social media networks were on fire after it was announced that a longtime friend, Wixárika land defender and attorney Santos de la Cruz Carrillo, had disappeared on Friday along with his wife and two children, including a three-month-old baby.

They had been taking their Toyota pickup truck to a mechanic in a nearby town on the rugged backroads of the cartel-infested Sierra Madre Occidental, where the states of Durango and Nayarit meet. Nobody had heard from Santos in 24 hours and so his companions filed a missing persons report and demanded that the government launch a top-priority investigation and find the family — alive.

Lea esta historia en español: Una familia perdida y encontrada, y la amenaza constante para los defensores de las tierras indígenas

This comes at a time when Mexico has been named the deadliest place in the world for land defense activists, particularly Indigenous people protecting their ancestral territories, according to the nonprofit Global Witness, which says 54 environmental and land defenders were killed in Mexico in 2021, as colleagues Anjan Sundaram and Rafael Lozano reported in an excellent piece in the Los Angeles Times and Yahoo! News, which Anjan just shared with me. But the problem goes far beyond Mexico, with violence against Indigenous land defenders prevailing throughout the Americas — including the US and Canada.

But why should we care? It’s because they are putting their lives on the line to defend some of the last fragments of biodiversity on the planet. They are leading the fight against runaway climate chaos that threatens us all. And they still, after 500+ years of colonization, are carriers of the seeds of a civilization that can co-exist in peace with the living planet that is our home.

The timing in itself was suspicious because Santos is the leader of a half-century-long battle to restitute nearly 11,000 hectares of invaded Wixarika territory. Just last week I saw the news that that battle had been won in the courts, and Santos was going home to celebrate this landmark victory with his community.

The last time a battle like this was in the headlines, two of its leaders were killed. That was in the Wixárika community of San Sebastian, when my friend Miguel Vazquez was gunned down in cold blood along with his younger brother in broad daylight for having the temerity to demand that the law be enforced and that their lands — also 11,000 hectares of invaded Wixarika territory — be returned. That was in 2016.

Now, in Bancos de Calitique in the neighboring state of Durango, Santos was just preparing to begin the next steps of this restitution process when he and his family were disappeared.

I use the transitive verb form here intentionally, as did other local media, because they didn’t simply disappear. They were taken.

The community sent out a declaration and demanded the government act quickly to find their leader. Saturday night many, me among them, tried to sleep through the horror of knowing that Santos and his family might never be found.

This hit me hard because Santos is the first Wixárika person I ever met, in the offices of AJAGI, the leading group supporting Indigenous peoples’ struggles to defend and recover their territories here in the western part of Mexico when I first arrived here in 2010. I went with the team of AJAGI that year to document that struggle and other territorial defense stories that were happening at that time and it was such an eye-opening trip that it inspired me to come back and work with them to document and support their struggle to save their most sacred site, Wirikuta, from Canadian mining operations. Santos became the key spokesperson and leader of that struggle, and we shared many hours and meetings and travels.

Last week when I saw the announcement that Santos’ long legal fight had at last been won, we connected over social media and I congratulated him. He invited me to his community to come and write about it. I could not believe that he would become another statistic.

So I awoke yesterday morning ready to write the story about Santos’ disappearance and his struggle to recover and defend his territories. As I perused the social networks, however, I was relieved to learn that Santos and his family had been found, unharmed.

The Nayarit Prosecutor’s Office reported that, with investigative and intelligence work, they had located Santos and his family “who are in good health.” In a statement, the Prosecutor’s Office assured that they would give more information about the investigation they had carried out in Durango and Zacatecas to locate the family.

No details of the disappearance have been reported, but this highlights the terrible danger that land defenders face throughout the region — Mexico is the worst right now, but similar conditions exist throughout the Americas. Regardless of what happened yesterday, Santos and his family are on the frontlines and are very vulnerable, and are far from alone.

I shared the news with Anjan, and as we were discussing yesterday morning, the work of covering these struggles is greatly impeded by the fact that mainstream news organizations are very reluctant to cover them — I personally have fought a tough battle to place these stories in national and international publications, which is one reason why it’s so important to maintain alternative platforms like The Esperanza Project. All of which leads me to thank those of you, from the bottom of my heart, for the support that you give to help keep The Esperanza Project platform alive and kicking.

But more to the point, the mainstream media gives minimal coverage to this ongoing massacre because we don’t want to look at it. As Anjan pointed out, we don’t want to look at the violent history on which our lands are built, throughout the continent. The work that Santos and his colleagues are doing is a small attempt to shift the balance just a bit toward justice that reaches back to the times of colonialism. That reckoning has begun in the US and Canada with the #landback movement, and it has taken a thousand forms, with individual landowners working with tribes to return portions of their ancestral lands, and with Natives themselves occupying treaty lands that have been stolen. Standing Rock was a part of that. So was the 4th of July occupation at Mount Rushmore, a defaced Lakota sacred site.

Those of you who have followed us for awhile may remember that last year, the Wixarika communities of San Sebastian and Tuxpan de Bolaños were marching 1,000 kilometers to the nation’s capital to demand followup in their own land restitution battle after the assassination of their leader paralyzed their efforts to recover the land in 2017. The year before, I had gone to San Sebastian to report on that land restitution fight and was received by Miguel Vazquez, leader of the movement. I stayed the night at Miguel’s home, ate breakfast at his table with his wife and the tiny daughter who adored him. I traveled with him to the first parcel that was being restituted by two families after the court officials signed over the rights. It was a 184 hectare ranch, just a tiny fragment of those 11,000 hectares.

Local law enforcement had refused to accompany them to take possession of the land, and the ranchers of the community of Huajimic, the community whose members had generations ago been wrongly granted title to that land by a corrupt government, blocked the entrance road and threatened violence. So the community organized.

More than a thousand of them walked together to the parcel, taking the back route through the mountains, and took turns accompanying the two families as they set up their homestead, and for many weeks until things had settled down, which was when I came to visit. Five months later, Miguel and his brother Agustín were dead, and it wasn’t until last year that the community had the courage to take up the issue again, this time under the leadership of schoolteacher-turned-authority Oscar Hernandez, who organized the march to the nation’s capital to demand support from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Meanwhile, back in Santos’ home territory, after the long legal fight and the victory, the most dangerous part of the work begins. I look forward to reporting on that as soon as I can finish the long-awaited Cosmology & Pandemic series, which also highlights Indigenous struggles to defend their territories and cultures and to keep alive a way of knowing and a way of life that can allow humankind to coexist with and even heal the planet. You will be seing A whole new episode of that series in these pages soon.

Indigenous peoples, who comprise around 5 percent of the world’s population, protect an estimated 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity. There’s a very good reason for that. If we can only listen and learn from them, follow their lead, keep them safe, and shift from our obsession with material accumulation and mass consumption, we might be able to reverse or at least slow down the multiple cascading crises we find ourselves enmeshed in.

Thankfully Santos is OK — for now. But I am painfully aware of his precarious position and that of literally hundreds of Indigenous land defenders. It is time to stop the impunity and the violence, and time to look within to see what we can do to support Indigenous land defenders like Santos who are putting their lives on the line to defend what remains of the Earth’s wild places. They are doing the work on behalf of all of us.

An earlier version of this story appeared in Mexico News Daily.

Thank you Tracy, for reporting. You’re right, the mainstream news isn’t reporting on this. It’s an invisible plague on our hearts and our spirits that has been going on since Europeans set foot on this continent.

I’m so glad they found them, and they will be in my prayers as they fight for what should have been theirs all along.