Editor’s note: In 2000, I was invited to help create what to this day has been one of the most beautiful journalism projects of my life, and one I think of as the predecessor to The Esperanza Project: Adelante, a bilingual newspaper aimed at bridging the gap between the rapidly growing Latino immigrant population of Central Missouri and the rest of the community. Founded at the University of Missouri’s Journalism School, it was an example of community journalism at its best. The reporters were Spanish-speaking students from diverse backgrounds, many of them Latinx themselves, and outstanding in their talent, commitment and humanity. Recently I was given the gift of a trip back to that time — and a reflection on the difference that project made in my students’ lives — by Rebecca Rivas, an accomplished journalist I had the privilege of teaching in those years. We share her story here with her permission. — Tracy L. Barnett

A Mizzou student asked me last month how I was able to succeed as a Latina journalist in a white-dominated industry.

The question followed a similar theme of those asked by other members of the Latin American Student Association, which had invited me to the university’s Columbia campus to speak as part of Hispanic Heritage Month.

Essentially, how do you honor your culture while working in a system that doesn’t always share the perspectives and values of your culture?

When I was an undergraduate at the Missouri School of Journalism, I was given a gift that I now realize was so rare – and it defined me as a journalist.

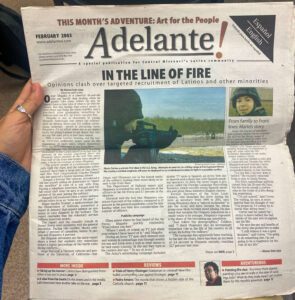

I had the opportunity to write for Adelante, a bilingual newspaper that was founded the same year I arrived at Mizzou by an adjunct professor named Tracy Barnett and members of Columbia’s Latino community. It was partially funded by the university, but mostly fueled by volunteers.

It was an experiment in not only bilingual journalism but also in community and immersion journalism. And it was successful.

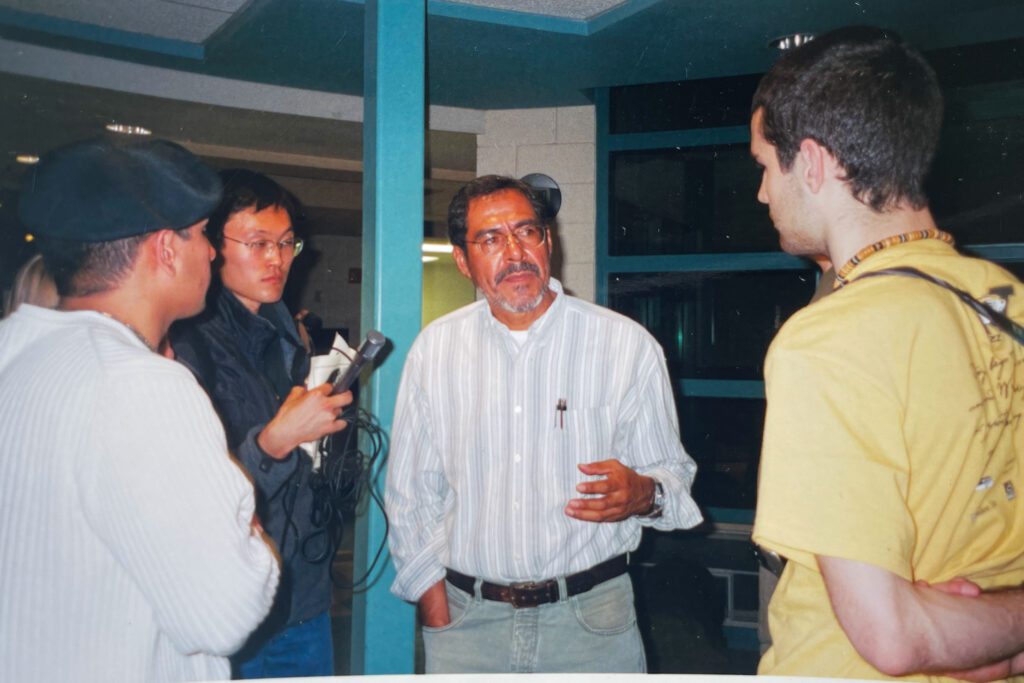

A main pillar of what I’m now calling the “Adelante method” was community building. Before we went out to report stories, Barnett, our editor, urged us to spend time just being in the community, earning trust and letting the stories happen organically. Not only would we go to community organizations’ meetings like the Centro Latino, but we also went to church gatherings and regular shows of a popular, local salsa band.

“We learned about the circumstances of people that there’s no way that you learn in a typical, reporting-type relationship,” Barnett told me in a phone interview this week. “You go to the appointment, you do the interview, they tell you one layer of reality, and then you write the story. That’s how most journalism happens.”

Barnett assigned us beats by geographic areas, and she highlighted the experience of Olivia Doerge (now Olivia Mena, a researcher on race for University of Texas,) who was covering the Jefferson City area.

“Olivia found out about a Baptist minister down there who was ministering to the immigrants,” Barnett said. “She just went down and hung out and she did whatever she could do to just be a part of that community.”

That’s how she learned that a Lake of the Ozarks resort was exploiting undocumented immigrants.

“She was able to document that and come up with a rather explosive story at 18 years old, and that was immersion journalism,” said Barnett, who now lives in Guadalajara, Mexico, and edits the online bilingual magazine, The Esperanza Project.

Adelante was founded in response to a social-service “crisis” occurring at that time, she said, where thousands of immigrants from Mexico and Central America were coming to work at the meatpacking plants and other factories in rural Missouri towns. These families were struggling to navigate finding basic needs like housing or health care. And our publication was a way to bridge the communication gap.

Adelante became my Columbia family. The other students were from Spain, Argentina, Peru, Cuba, Japan and various parts of the country. Some of us were Spanish-speakers, and some of us weren’t. Our translators were from Columbia’s Latino community and from departments throughout the university system.

“There was so much diversity even in our own group, that it led to a much richer, more interesting kind of coverage and perspectives,” Mena told me, reminiscing last week.

I reached out to several former reporters to understand how Adelante impacted their lives.

Like me, Marina Walker Guevara, now executive editor of the Pulitzer Center, attributes much of her success and the way she approaches journalism to Adelante.

“It was at Adelante when I first experienced that my diverse background was really an asset and not a liability,” said Walker Guevara, who was a graduate student from Argentina at the time, “and not something that I needed to overcome to work in the U.S. and to succeed as a journalist.”

David Barreda was a photographer for Adelante, and he’s now a photo editor for National Geographic. Getting involved in Adelante was a turning point for him, he said, because it helped him “recenter his identity” as a Peruvian.

“I could have gone through two years in Missouri and not really stepped outside a lot of Columbia and seen Latino Missouri,” Barreda said, “and what was impacting so many community members.”

The Adelante method — of centering people’s voices and earning trust — helped me cover the Ferguson uprising, where I was able to get exclusive access to key people and moments to document how the movement changed politics locally and nationwide. That work was a finalist for the 2022 duPont-Columbia Award.

Adelante was never fully funded, and it eventually folded after about six years.

After speaking with students last month about Adelante, several jumped at the idea of bringing it back. One student came up to me in tears, saying that she’s thinking of leaving the university because she felt out of place. I saw myself in her because while Mizzou has an amazing journalism program, I may have left as well had it not been for Adelante.

Adelante helped me find a path to being a journalist that honored my community, along with other marginalized communities that often don’t feel they have a voice or can trust journalists. And I’m so grateful for that.

This article was originally published in Missouri Independent on October 10th and is reposted here with the author’s permission.

- The ‘Adelante method’ helped me succeed as a Latina journalist - October 12, 2022

Olivia Doerge representin’