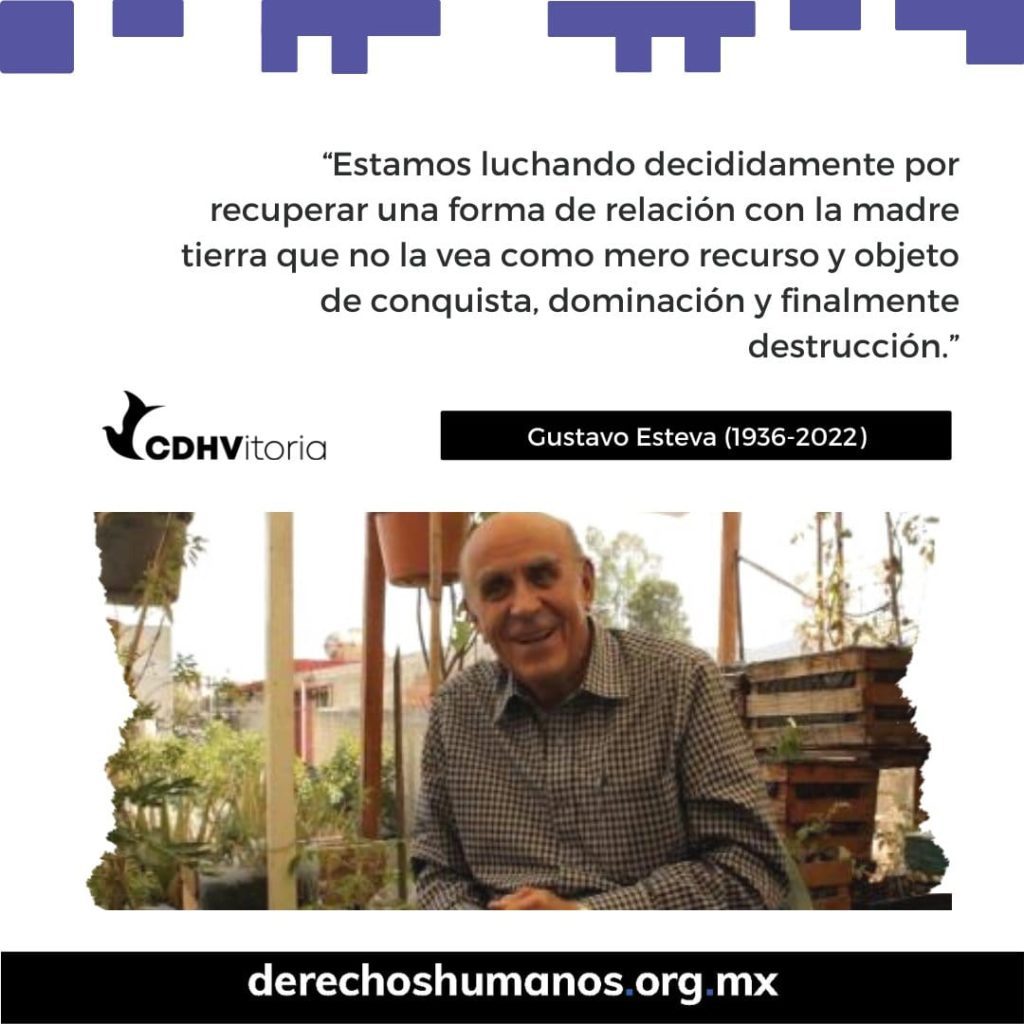

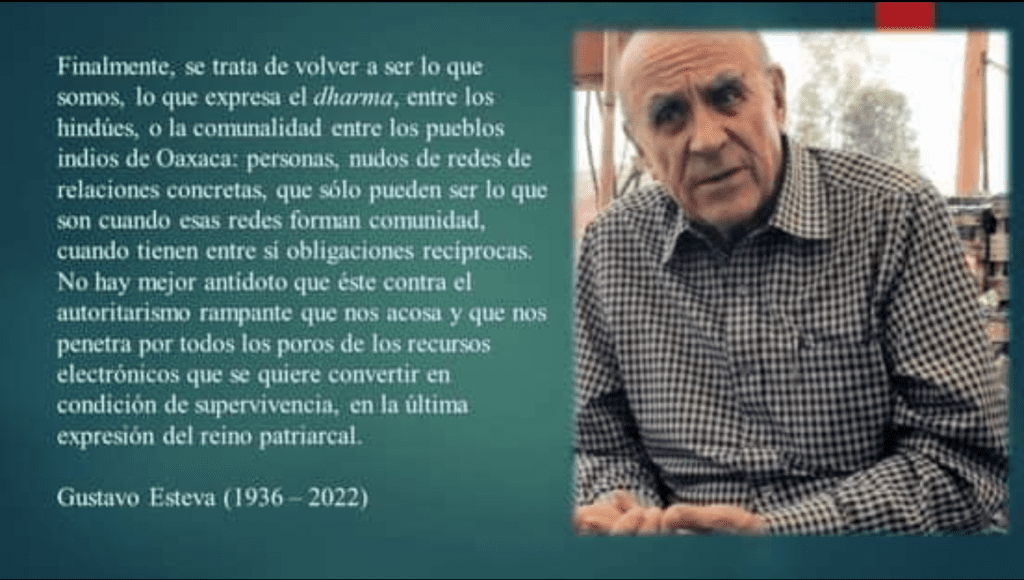

I dedicate these farewell lines to Gustavo Esteva, an exemplary teacher of life, who, like his friend and contemporary philosopher Ivan Illich, dared to develop and put into practice revolutionary and comprehensive education systems. His groundbreaking work was aimed above all at “those from below:” peasants, indigenous people, young revolutionaries, and ex-guerrillas.

I am not going to write a biography of Gustavo, a task that several people who worked more closely with him and knew him much better than I are already doing. But I am going to write about some episodes of his life that influenced mine, and for that I am going to write this LETTER TO GUSTAVO to share a few of the ways I have managed to put into practice what I learned from him since I became aware of his existence and work in his tour of life.

Dear Gustavo:

I would like to tell you something about my life path since we met, because we did not have the opportunity to meet in recent years.

After I abandoned the professional training that the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) offered me in 1968, having started careers such as chemical engineering, economics, political science, psychology and philosophy without completing any, I began to read some texts by Iván Illich that anticipated his book: “The Deschooling Society.” Additionally, I received from my cousin Claude Lasterade the radical essay “Misery in the Student Environment” by the Situationists Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem, which I translated and disseminated in 1968. It became clear to me, as it did for Illich and for you, that my path would not be professionalization, but like you, that of deprofessionalization.

Following that path, and after discarding the paths of “neoliberal success,” party politics and Guevarist guerrillas, years after more than a decade touring many worlds, on the way to finding a different option, in 1982, with an international group of artists and social activists, we founded a tribal community on the slopes of the Sierra del Chichinautzin, in the Mexican state of Morelos, called Huehuecóyotl, with the intention of putting into practice and experiencing what would be a radical change of life once we added to the nomadism, performing arts and social activism, the practice of ecology.

Several of our new neighbors and friends began to tell us about their experiences in Cuernavaca at the Centro Integral de Documentación (Integral Center for Documentation, CIDOC), founded by Iván Illich himself. The Center had unfortunately disappeared in 1976, although several of them had participated and continued to implement his theses and proposals. Among them, although you were not part of CIDOC according to what I have read, the most recognized writer and thinker was you, dear Gustavo, father of one of our new friends in Tepoztlán, whose name I now no longer remember.

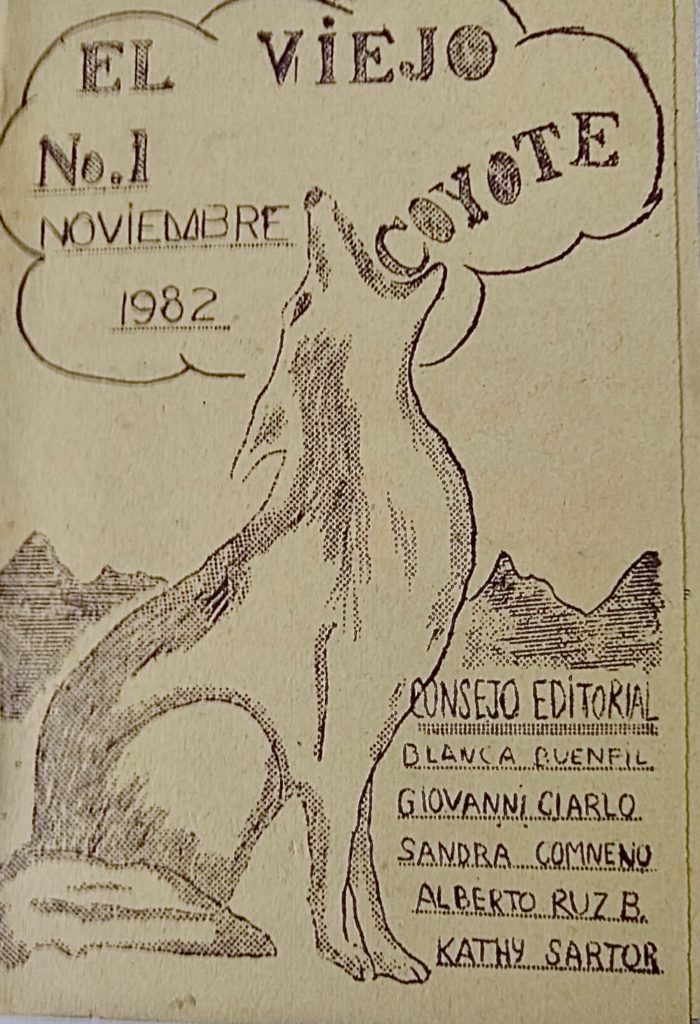

Our purpose from the beginning was not and is still not that Huehuecoyotl be just a small private paradise for us and our descendants, some of the ideological survivors of the principles in which we believed in 1982, but rather to create a network of similar projects. So with a small group of the new Huehuecóyotl community members, among them very especially my partner Sandra Comneno, a co-founder of the village, we decided to launch the first issues of a small craft magazine, printed on a manual mimeograph and a stencil, since for the first five years of our settlement on a 2.5 hectare plot we did not have electricity.

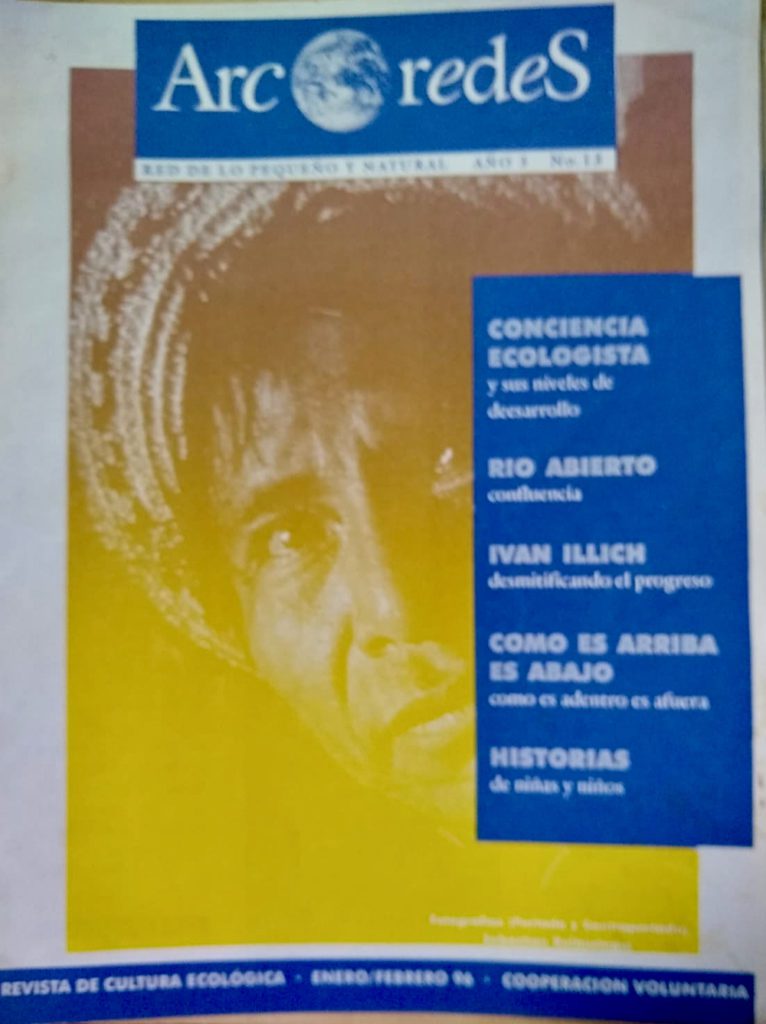

The magazine, which we first called “Las Voces del Viejo Coyote (Voices of the Old Coyote),” and later “ArcoRedes,” began to attract the first ecoactivists and related groups that began to emerge in Mexico, with whom we joined as a publishing cooperative that began to spread in other states, and which subsequently attracted other similar initiatives in Europe and the United States.

By then, we had electricity and the quality of the magazine was gradually improving, self-financed by each of the groups or associations buying one or two of its pages, to share their experiences with others and to publicize environmental issues and some of their solutions in broader sectors of society. The network that emerged from these alliances was called “Red Alternativa de E/COmunicacciones” (Alternative Network of E/Communications), and a more elegant version of our magazine that we baptized “Arco Redes, Network of the Small and Natural.”

We can without boasting affirm that this was the beginning of the incipient autonomous environmental movement that was emerging in Mexico, which three years after the first seeds were sown in Huehuecóyotl, managed to carry out with the Alternative Network in 1985 the first, and to date only, National Meeting of Ecological Groups in the country of which I have memory. These steps made it possible to share experiences which were the bases for later some of its members to create both the Pact of Environmental Groups, an association called “Mexican Ecological Movement,” and even the Mexican Green Party. With these last two, I don’t really feel identified at all.

However, the publishing cooperative was unable to continue doing its work due to lack of funding, although some of its adherents continued to publish “ArcoRedes, Network of the Small and Natural” for several years with advertisements from small businesses that began to buy commercial space in their pages to promote and sell their products, always kind to the environment.

I personally understood that it was not possible to continue in this marginal scope, and I began to try to publish my articles in some magazines or newspapers with a national circulation, finding that none of these media, right or left, had any interest in environmental or ecologist themes. As I came to define it at the time, “Ecology was almost a dirty word,” and articles were systematically dismissed as “apocalyptic or alarmist.”

It was then that in 1984 a copy of the weekly supplement of the newspaper “El Día” fell into my hands, called “El Gallo Ilustrado,” and I learned that its director was none other than you, Gustavo, who since then we considered to be our “older brother,” mentor and teacher. “El Gallo” was founded in 1962, and was focused on literature, science, visual arts, theater and cinema, and was the only one that was then publishing the first articles by authors and eco-social activists who had to do with addressing those issues until now despised by the rest of the great national press.

Among your collaborators, you had renowned writers and personalities such as André Gorz, Iván Illich, Kostas Axelos, Jean Robert, Valentina Borremans, Pierre Clastres, Mark Kinney, Gunther Hoffman, Wolfgang Sachs, Satish Kumar, Verónika Bennholdt-Thomsen, Robin Roy, Arne Ness, Michael E. Souli, and Roberto Aitken Roshi.

In addition, I also want to mention some collaborators with whom I had a personal connection, such as Garrick Beck, co-founder of the Rainbow Nation Without Borders Movement and son of the creators of the Living Theater, Julian Back and Judith Malina; Charlene Spretnak, co-founder of the Green Party of Canada; Gary Snyder and Murray Bookchin. Of these last two, Bookchin, the first of the eco-anarchist historians, ideologues, activists and theorists, author among others of the books “Post-Scarcity Anarchism” and the “Ecology of Freedom,” and originator of the Social Ecology current, became my mentor and friend in 1968, when we met in the countercultural movements in New York, and with whom I have maintained an enriching dialogue ever since. We met again a year later at the Pont de la Ghisolfa, headquarters of the anarchist magazine “A,” located in the city of Milan, with which both Bookchin and I collaborated, continuing our epistolary exchange until a few years before his death in 2006.

The second, Gary Snyder, who continues to be one of my great cultural heroes, the Beat poet-prophet of the community movement and the new tribalism in North America, also a very important source of inspiration, with whom several of us shared an unforgettable night in a tone of a campfire and his home in the state of Nevada, and from which my traveling companion Andrés King, now a neighbor and co-founder of Huehuecóyotl, published a book of poems in the UNAM publishing house.

I went immediately to see you, as you remember, and I told you everything we had been doing since 1982, as well as the difficulties I had encountered in continuing to support an alternative magazine in those years. After patiently listening to me, you offered to add a new section to the Gallo Ilustrado literary supplement, which I obviously gladly accepted, thus finding a way to finally be able to reach many more readers, eco-activists and groups interested in Ecology at the time, not only in Mexico City but also throughout the rest of the country.

The new section, which I considered a “literary asylum,” would be an extension of our first craft magazines and ArcoRedes, and which Sandra Comneno and I baptized as “Spaces of Freedom,” to which I immediately invited some of the most visible and coherent spokespersons of the incipient Mexican environmental movement, mainly those from the Pact of Ecological Groups and the collective Group of Environmental Studies of Tlalpan. Mainly, in addition to you, Gustavo, were Jean Robert; Alfonso Gonzalez Martinez; Margot Aguilar R.; Luis López Llera, Regina Barba, Alejandro Calvillo Unna and José Arias Chávez, who were also joined by Sergio Jácome, Christopher Flavin, Pablo León Juárez and Mónica Navarro Ruiz, among others.

Then you gave us the absolute freedom to include all the articles that Sandra and I were receiving, from Mexican authors and ecoactivists, and from texts that ecoactivists from Europe and the United States sent us, and that we were in charge of translating.

In No. 1146 of “Gallo Ilustrado,” in June 1984, I published my first two articles, “Huehuecóyotl; el camino de la u-topia a la ecotopía (Huehuecoyotl: The path from u-topia to ecotopia)” and “El Teatro y su Unidad (Theater and Unity),” and from that year I continued to collaborate periodically with you, until the year 1988, in No. 1353, both as a columnist and sometimes also as a caricaturist and photographer, leading the coordination of the Spaces of Freedom with Sandra, both of us exponents of the experiences that we then called “Laboratories of Utopia.”

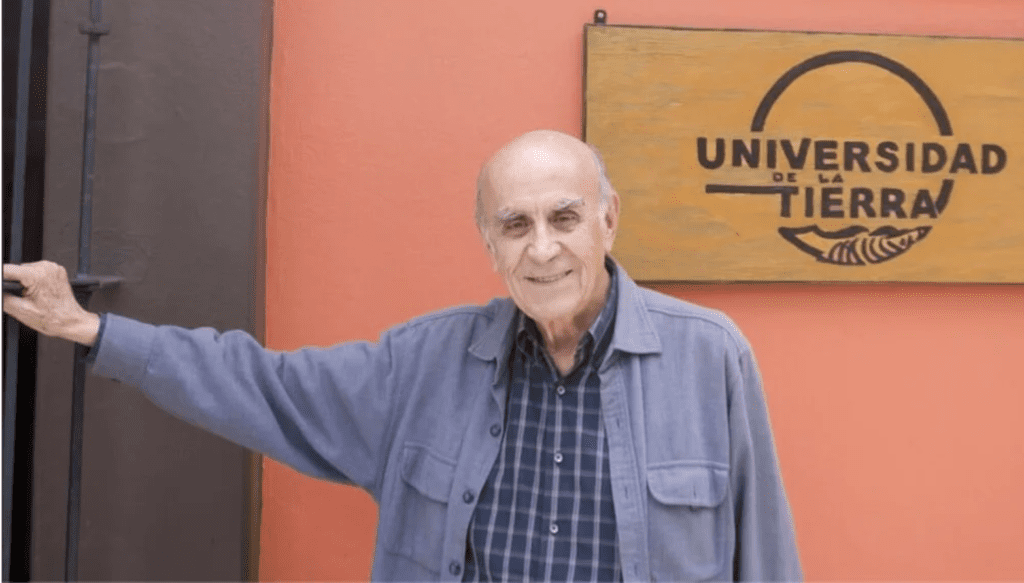

— Gustavo Esteva (1936-2022) (Source: University of the Earth Facebook Page)

In the year 1983, our mutual friends and comrades-in-arms from Ponte della Ghisolfa in Milan published a book titled Laboratori d’utopia from Ronald Creagh and the publishing house A Antistato; inspired, among others, by Murray Bookchin and Paul Goodman and with which I have collaborated since 1979, in which a chapter of my authorship was included, “Dopo il 68” (After ’68, a journey in the community archipelago of the United States).

A couple of years later, in 1986, following the Chernobyl catastrophe in the Soviet Union, Sandra and I toured a large part of the European countries to collect testimonies of the actions of dozens of groups and anti-nuclear movements, which were published in Gallo Ilustrado in the Espacios de Libertad section and in the Casa del Tiempo of the Autonomous University of Mexico, which were also welcomed by its director, friend and comrade in struggle, Javier Sicilia.

I met you again, dear Gustavo, in 1994, during the National Democratic Convention called by the National Zapatista Liberation Army, or EZLN, held in San Cristóbal Las Casas and in the Zapatista camp of La Realidad, Chiapas, which I attended as a delegate accompanied by a young activist, coordinator of ArcoRedes magazine, Paula Willis, representing and contributing a collective document of the Morelos environmental movement to the discussions to elaborate a new National Constitution.

In those years, you were serving as an intermediary in the negotiations between the federal government and the EZLN for the San Andrés Larraínzar Agreements signed in 1996 so that the rights of indigenous peoples, their lands, territories, uses and customs and their autonomy would be respected and guaranteed. As always Gustavo, a Quixote in the front line of the fights for all good causes.

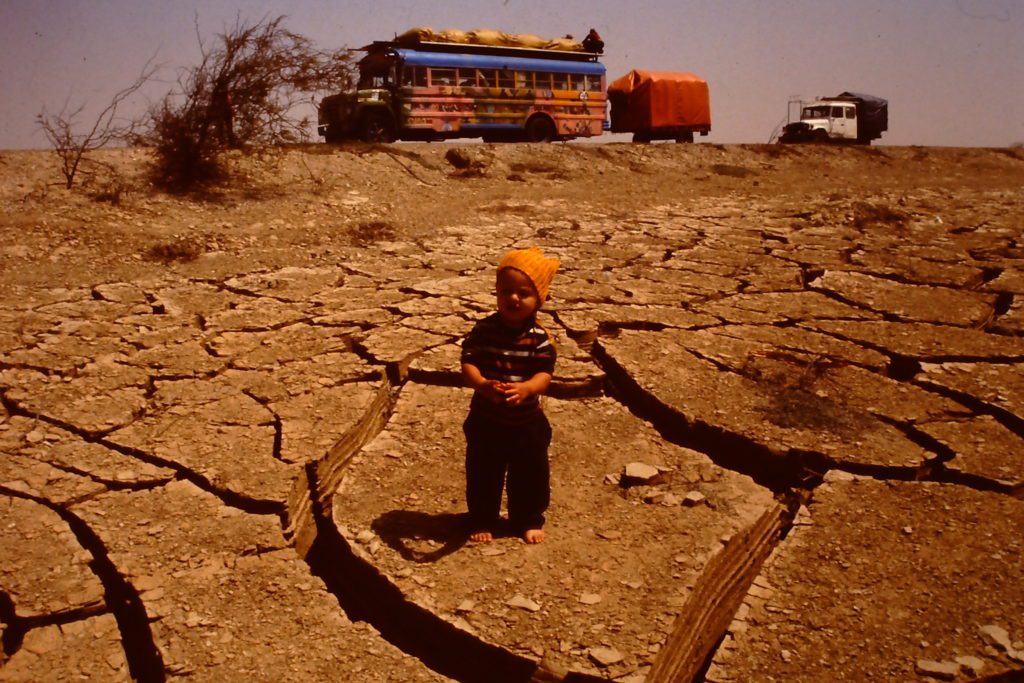

In the summer of that same year, I left Huehuecóyotl and Mexico with a fortnight of crew-volunteers aboard an old bus converted into a common mobile home, a project we call the Rainbow Caravan for Peace, with the purpose of make a trip by land to Tierra del Fuego, to share our community and educational experiences in Mexico, carrying the voice of a Council of Indigenous Nations gathered in Guatemala, made up of representatives of their nations in the Americas or Abya Yala, and as an itinerant arm of the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN for its acronym) to disseminate and support the first eco-community experiences on the continent.

As we passed through Palenque-Chiapas, we received an invitation from the Zapatistas to participate in the Intercontinental Meeting for Humanity and against Neoliberalism (also known as the Intergalactic Meeting) in some of the “Caracoles” that had been established in Zapatista territories and in La Realidad, headquarters of the EZLN.

After spending a few days with the compañeros of the Caracol “Roberto Barrios”, we went into the jungle with our mother ship, “La Mazorca,” and remained camped in La Realidad on a hill next to the camp where more than 3,000 delegates were preparing for the arrival of the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee (CCRI) and Subcomandante Marcos.

Our camp was designed as a model of what after 13 years we would continue to replicate with the Caravan in 17 Latin American countries, with all the elements of a “temporary settlement” provided with “Ecotechnologies” enabling us to care for our impact on the natural and cultural environment of each of the hundreds of villages, indigenous communities, favelas, Afro-Brazilian quilombos, towns, neighborhoods and cities where we spend time offering courses, workshops, conferences, talks, festivals and ceremonies, but above all living and learning daily with its inhabitants , of all ethnicities and ages.

La Caravana was chosen in 2000 by the Global Ecovillage Network as a Living and Learning Center in Colombia and as its first itinerant ecovillage model to put into practice the theses and libertarian educational practices of Iván Illich, Paulo Freire, Paul Goodman, and above all, yours.

In Brazil, where the Caravan remained for four years thanks to the support of the Minister of Culture Gilberto Gil, we toured a large part of its vast territory, visiting and interacting with more than one hundred Living Culture Points, almost all of them located in areas least served by any governmental program throughout the country’s history, and I can add throughout Latin America, and giving visibility to the cultural and spiritual manifestations of the widest diversity of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants of dozens of indigenous communities, Afro quilombos and favelas of the great Brazilian megalopolises.

Learning and teaching, following your example, Gustavo, that you later put into practice in Oaxaca, Chiapas and other states of Mexico and other Latin American countries as far as your revolutionary influence and example reached.

In 2007 we were chosen and honored with the Escola Viva (Living School) Award in Belo Horizonte by President Lula and his Minister Gilberto Gil, as one of 60 projects of the Escuelas Vivas Network, the only one made up of a crew of international trainees and facilitators, and also the only itinerant one, educators who have followed in your footsteps and above all disseminated the bioeducation lessons that both you and Paulo Freire bequeathed to us as your principal legacies throughout your lives.

The Caravan concluded its stay, not only in Brazil but throughout the Continent, for thirteen years and in seventeen countries of Central and South America, setting up a temporary Peace Ecovillage within the framework of the World Social Forum in Belem de Pará, Amazonia, in 2009, which received more than 100,000 social and environmental activists from 142 countries, six Latin American presidents, thousands of indigenous people and journalists from around the world, and many volunteers. The port city of Belém was literally “taken over” for a couple of weeks by hundreds of camps of participants, but the Temporary Peace Ecovillage, which housed 2,500 people, was the only one with ecological design at the entire great event, just as we did for the first time in La Realidad in 1996.

Upon my return to Mexico in 2009, 13 years after my departure, I was invited to continue similar work in 10 towns, neighborhoods of the Coyoacán Delegation in Mexico City, thanks to the support of the then General Director of Culture Laura Esquivel, today appointed Ambassador of Mexico in Brazil, and its deputy director, historian and author Antonio Velasco Piña. After consulting with a team of facilitators, we offered a project to present theoretical, practical-experiential training to more than 450 Ecobarrios Promoters of all ages who were interested in participating in the program, replicating the work carried out in 1994 during the administration of Mayor Antanas Mockus, philosopher, mathematician, politician and educator, former rector of the National University, for having supported the creation of a dozen Ecobarrios in the city of Bogotá.

In recent years, on a tour of presentations and conferences in various states of southern Mexico and passing through Oaxaca in 2012, I took the opportunity to visit you at the headquarters of the Universidad de la Tierra or Uniterra, inspired by you, dear Gustavo, an exceptional project of education, as always for those “from below.” The example of this result, which arose from the initiative of a coalition of civil organizations, teachers and indigenous promoters from Oaxaca, has served, among other achievements, to be replicated in Chiapas, Puebla and California, following the foundations of a deprofessionalized education model, as you yourself baptized it.

We did not know that it would be the last time we would meet in this human dimension, but in 2016, a small group of visionary fellow travelers, including César Daniel González, Salomón Bazbaz, Verónica Sacta, Tiahoga Ruge and Arnold Ricalde, convened and organized the 1st International Forum for the Rights of Mother Earth in Mexico City, for which we extended a special invitation to you as one of the most lucid, coherent, and courageous eco-educators and social activists in Mexico.

You could not attend, but we had, among fifty artivists, as many of us identify ourselves, more than 10,000 attendees, both at the thematic Forum, the Pachamama Fest and the assembly of a temporary Peace Village in Parque Mexico In the Condesa neighborhood of Mexico City, and with the support of hundreds of volunteers, none other than Leonardo Boff from Brazil, Vandana Shiva from India, Mateo Castillo from the Earth Charter Mexico, and Natalia Green and Esperanza Martínez Yáñez from Ecuador arrived at the Forum, as did Ati Quigua from Colombia, María Sánchez from Harmony with Nature from the United Nations and Saamdu Chetri from Bhutan, among others. The 1st Forum has been followed by the 2nd in Sao Paulo, Brazil, the 3rd in Bogotá in Colombia and the 4th to be held in Santiago de Chile to bring this year 2022, to its new Federal Constitution, several articles to recognize and adopt regarding the Rights of Nature/Mother Earth.

This initiative, in which Verónica Sacta and I have worked hard since our time with the Rainbow Caravan in 2005, and years later upon our return in 2018, has just achieved a major milestone: that a majority of the new members of the Constitutional Convention were ecologists or environmentalists , as well as for the first time in the history of Chile, an equal number of women and men — and 17 of the 155 seats were reserved for indigenous peoples.

On March 11, 2022, the 36-year-old then-presidential candidate Gabriel Boric, representing a post-Pinochet and neoliberal generation, was elected with a large majority of votes, and on the 25th of the same month, the Convention approved seven new articles out of nine presented. Among them was the historic decision to recognize the Rights of Nature/Mother Earth, the protection of the environment and natural biodiversity, as well as measures to face the climate and ecological crisis and to promote environmental democracy and animal rights.

To close this long epistle, as befits those of us who have already traveled many paths like you, dear Gustavo, it is now my turn to be the mentor of those who come.

You are, have been and will continue to be one of the greatest examples in all of Latin America for those of us who have followed in your footsteps, and I thank you, on behalf of everyone, wherever you are, for having left your very clear and indelible footprints on the skin of our house and common mother, to be able to continue walking our words and our visions.

Thank you for everything.

Always,

Coyote Alberto Ruz Buenfil

The bimonthly electronic publication edited by the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores del Occidente (ITESO), Magis, in its 448th edition, published a magnificent biography and report on Gustavo Esteva, by the author Rubén Martin, titled: “It is important to recover hope as a social force,” as well as other biographies, reviews of several of his books and hundreds of articles and interviews with Gustavo, to learn more about his work throughout his prolific years of impeccable service to humanity and to Mother Earth.

My article-letter does not intend something similar to what other authors have written and will write about this personage, but it is just a very personal account of some anecdotes that I have collected over the years, that came back to my memory when I heard about his death. I hope it can serve as a worthy addition to the dozens if not hundreds of tributes that have emerged to honor the life of a true teacher and servant of Mother Earth.

I find it so beautiful and inspiring, the work you have done, Alberto. Thank you for sending this letter. So many of us are unaware of these movements, these leaders, and the messages they lived through their lives, the creativity, the wisdom, and the power of collaborative energy they demonstrated. I want to see and plan to create more of this energy in my own community. Thank you for showing us the way.

Dear Alberto, Greetings from the cool blue north! Muchisimas gracias for this fine letter, which helps us all to know something more of the path you have traveled and the way your work resonates with Gustavo’s work and so many others you mention. I felt so lucky to meet Gustavo in Oaxaca at our bioloco celebration a couple of years ago. I was saddened to hear of his passing. Don Gustavo, presente.