It’s hard to believe it’s been eleven years since I met the colorful characters who peopled the Rainbow Peace Caravan and the Vision Council: Guardians of the Earth. And it’s been almost a decade since the caravan returned from its 13-year sojourn through Latin Amerca and dived headfirst into the gritty marginal neighborhoods of Mexico City’s Coyoacán area.

This story, which was first published in The Esperanza Project on Oct. 12, 2012, was selected for the forthcoming book Ecobarrios en América Latina: Alternativas comunitarias para la transición hacia la sustentabilidad urbana (Eco-neighborhoods in Latin America: Community alternatives for the transition to urban sustainability), Alberto Ruz Buenfil, Beatriz Arjona Bernal, and COOPIA, eds., (México / Colombia: CASA Latina, 2021).

It had gotten lost to the vagaries of the Internet when the site was hacked in 2013. But the invitation to contribute it to the book was the motivation we needed to resurrect it and repost it to our website, together with photography by Mexico City photographer Daniel González and yours truly. The story and the event are as relevant today as they were then, and Clorofila, Alberto, Veronica, Arnold, Noelle, and many other longtime members of Organi-K and the Rainbow Peace Caravan continue to change lives and neighborhoods throughout Mexico and beyond. Indeed, Alberto Ruz has just come out with a new book, El Correo de los Cuatro Vientos: Ecos de Tlatelolco — but more on that later. For now, inspiration from the Ecobarrios troupe in Mexico City.

Antonio Sánchez Gramiño was always one of those who would shake is head and laugh when he heard people talk about changing the world. It’s not that he didn’t care; he’s always been ecologically minded. It bothered him to see people wasting water and creating trash. It’s just that he thought it was a lost cause.

“I used to call them pendejos (fools),” he told me with a laugh. “Now, I’m one of those pendejos.”

Para leer este artículo en Español haz click AQUÍ

Antonio, a retired administrative government worker, lives in the southern Mexico City delegation of Coyoacan, where local activists worked with city government in a three-year program to turn their neighborhoods into ecobarrios, ecologically sustainable neighborhoods. He was walking his dog in Huayamilpas Ecological Park when he ran into Clorofilia, one of the environmental educators at Organi-K, doing a presentation on eco-technologies: a whole lineup of simple, do-it-yourself devices like bicycle-powered kitchen appliances, solar-heated showers, activated charcoal water filters and composting toilets.

The contraptions caught his attention, but what kept it was the passion he saw, not just in Clorofilia – otherwise known as as ecobarrios educator Anahí –but in her fellow activists. “I’m old enough to be her father – even, perhaps, her grandfather. But I want to be like her.”

Toño, as he likes to be called, is one more than 300 local residents who have undergone a training program to become Ecobarrios promoters. They say the program has changed not only their neighborhoods, but also their lives.

Clorofila, a.k.a. Anaí Martínez, leads a group of students on an eco-techniques tour. (Photo by Tracy L. Barnett)

But the program’s future is now in doubt, as the government that sponsored them is reaching the end of its term, and with it, the group’s funding has come to an end.

Launched as an initiative of Laura Esquivel, the celebrated author of “Like Water for Chocolate” and outgoing Secretary of Culture for Coyoacan, the Ecobarrios program gave a temporary home to the itinerant band of environmental educators, artists, performers and magicians known as the Rainbow Peace Caravan, together with the Mexico City-based nonprofit group of permaculturists, Eco-Gaia educators and alternative technologies experts from Organi-K.

I met this group in January 2010, just as the Caravan had returned from 13 years traveling through the Americas, teaching sustainability skills in war zones and favelas, remote indigenous villages and crowded urban slums from Mexico to Patagonia. They had barely landed back where they started, at the ecovillage of Huehuecoyotl, when caravanista Alberto Ruz connected with Laura Esquivel. She invited him to put the lessons of the Caravan into practice with at-risk youth in some of the outlying neighborhoods of Coyoacan – a task Ruz and friends embraced with the same passion and creativity they had carried with them all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

Their job was to reach out to some of the poorest neighborhoods of the delegation – far beyond the beautifully preserved, upscale colonial center of Coyoacan and into the sprawling, working-class suburbs, where thousands are in a daily struggle for survival. Their goal was nothing less than reconnecting the denizens of this urban jungle to their native roots, and to the beating, living heart of the Earth below their feet. By many accounts, they were successful.

“It’s a dignification of people who find themselves in a critical situation, deprived of opportunities,” explained Victoria Martinez, a lively octogenarian who sat quietly on the edge of a group of new graduates, her daughter Maria among them, as they worked together to compose an ardent letter to the new government explaining the value of their work and asking for continued support.

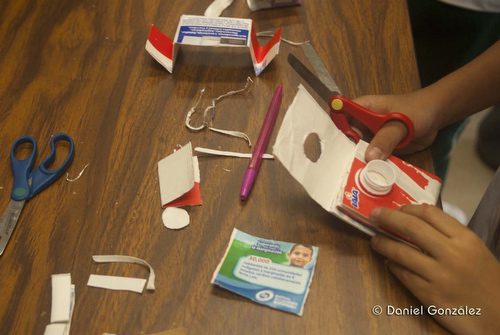

“In the workshops, we learned to give life to discarded items – and there are so many of them – in ways that have a lot of imagination, helping us to develop artistically.”

Downstairs, in the photo exhibit area, Victoria’s and Maria’s faces beamed from a framed photo, surrounded by lush green plants they were nurturing in one of the pockets of urban agriculture created by the group in this zone of graffiti-stained cement and ragged patches of weeds.

During its nearly three years of work, the group had conducted extensive programs in ten different neighborhoods of Coyoacan, holding four-weekend training sessions with hundreds of schoolchildren and more than 300 adults who are now environmental educators and community organizers in their own right.

Now, however, the group is ending another cycle, and once again wondering what the future will bring. They marked the end of this cycle with a weeklong series of events in September to celebrate nearly three years building a culture of sustainability – or “geoculture,” as Veronica calls it – in some of Mexico City’s poorest neighborhoods.

Titi Gless y Zambomba (Foto de Daniel González)

During the three-year program, they took their itinerant demonstration of ecotechologies to more than 13 different sites, and established two prototypes of community gardens in two Cultural Centers, with all the complements of capture, storage and reuse of rainwater, various systems of organoponics, hydroponics, green roofs, vertical gardens, solid waste separation centers, composting, and much more. In both sites, volunteers will continue developing practical courses for the teaching of different systems of urban organic agriculture.

But all these activities are just what occur on the surface, said Ecobarrios leader Veronica Sacta Campos. The underlying goal is much deeper.

“We’re trying in some way to bring this energy of the Mother Earth and move it into action, bringing forth her abundance but in a way that is reciprocal and respectful,” she said. “We are trying to create a circle in which there is space for everyone, a space of trust, in which each one can manifest their voice – in which we all grow together, as individuals, as a group and as a movement.”

That space of trust was just what 18-year-old Diana Estrada needed to move from teenage angst to empowered activist.

“For me it was a 360-degree turn,” said Diana, whose parents sent her to the class to distract her. “I didn’t have any particular interest in ecology. I had no idea I would fall in love with this project.”

She was shocked to learn that her own habits were having an impact on the planet – the fact the Styrofoam takes so long to disintegrate, for example. “Just to be able to walk to the corner and buy a cup of atole or coffee and for this cup to be here for 500 years… no, no, no.” Now she’s a leader in the group and is helping to develop one of the demonstration centers.

For Rachel Aldana Martinez, a young biologist from Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, the need for conservation has been a driving force for many years; but until now, she hasn’t been able to build a cohesive environmental group in her home state. The Ecobarrios program has given her tools to take home with her and build an organization. It’s also given her something deeper:

An understanding of our spiritual connection with the Earth, something she believes will motivate people in the essentially very spiritual community of Los Tuxtlas.

“This is what I have realized: We have to return to the ancestral question, that we are all part of a single whole, that we are in reality an equilibrium together, that we are not separate, and that we ourselves belong to the Earth – and our lack of understanding of that is what is causing so much destruction.”

As Rachel shared plans for her return to Los Tuxtlas with me, the African drums of Titi Gless and Zambomba were beginning to shake the timbers. As I’ve come to expect from this group, they were going all out with a week-long, action-packed program. Environmental education combined with music, dance, theater, art and dialog. From the stage, a theater troupe of Amazon-style dancers and drummers set a wild backdrop for a woman dressed in pearls and heels and gold lamé, finding her way to a deeper, more meaningful way of life.

Upstairs was a workshop on composting with earthworms and another on building urban chinampas, a modern adaptation of an ancient Aztec agricultural method. In the forum was a discussion on solar energy; along the corridor, small farmers and producers were selling artisanal cheeses, organic macadamia nuts, wallets crafted from recycled bags, exquisite indigenous beadwork and much more. In another area, an artist was explaining how she used old bottles to create colorful works of art, and Clorofilia was giving a group of schoolchildren a tour through the ecotecnias display, explaining alternatives to the modern flush toilet, a modern convenience responsible for the contamination of billions of gallons of fresh water daily.

“So when you flush, it makes its way down here to the sea, and these fish are swimming in it,” she explained, as they looked on, fascinated and horrified. “It sounds really awful, and it is – imagine! All these sharks and fishes are eating it – and it’s not their fault!”

Behind the stage gleamed a winding, iridescent, postmodern Quetzalcoatl made from discarded CDs and DVDs. Overhead, medicinal plants sprouted from discarded rubber gloves dangling from the steel rafters. Everywhere you looked, discards were repurposed into art: television sets, radiators, old potato-chip bags and soft drink cans.

This dynamic interweaving of culture and ecology is an art this group perfected in their journeys throughout the continent and especially during four years developingthe “Points of Culture” program in Brazil for the National Office of Culture under the direction of then-culture minister Gilberto Gil. They had hoped to do something similar here in Mexico but were met with a hard reality: The Mexican bureaucracy moved so slowly that it took an entire year for any funding at all to be made available. The second year, the scant funding wasn’t nearly enough to cover costs.

The whole first year of the program the staff of 13 worked on an entirely volunteer basis, with the volunteers themselves investing thousands of dollars of their own money for materials and transportation, with the hope that it would be eventually paid back. So they had to improvise, and it was during that process that they came up with the idea of developing a training program for ecobarrios trainers.

“The idea was to train people so that those people could do projects, and to give them experiential tools in theory and in practice, so that they could organize themselves and make changes in their personal, family and social lives,” said Alberto Ruz.

Building the program from nothing was one of the most difficult challenges the group had ever faced. “The lack of familiarity with the concept of a sustainable culture went from Laura Esquivel on down,” said Ruz. “Neither the people in the Culture Ministry nor in the Coyoacan environmental department knew of any precedent of a program that blended culture and environmental education.”

In the beginning they encountered a lot of suspicion, Alberto said. One of the challenges was that government-sponsored programs in Mexico typically revolve around free handouts of some sort. “When the people realized we hadn’t come to give something away, they asked, ‘Who are these people?’”

Making matters worse is that the Green Party in Mexico has been linked with corruption for many years, a reality that has stained ecological politics, generating further mistrust from an already skeptical public. These were all factors that had to be overcome.

Veronica took to the challenge like the weaver of a delicate fabric, carefully connecting the threads of their group with those of the community and the institutions they were working with, finding ways to build alliances.

“It was like caring for the beauty of a precious heart, with the greatest subtlety, the greatest love, the greatest transparency and sincerity possible.”

Now the success of the Ecobarrios program is becoming evident in various initiatives that some of the groups are launching on their own – such as the group in Santo Domingo, which wrote a grant to get funding for an award-winning multifaceted project to recycle, compost and reuse wastes in their neighborhood, and an alternative healing group that has created a green roof for growing medicinal plants, which they’re using to create natural medicinal products.

“But the changes are more profound than they are visible,” said Alberto. “When you change a person, they can change many other people.”

He might have been speaking of any one of the 300 newly trained activists – but the one who reached out to me as I prepared to leave was Hernán Juárez. He had just delivered an impassioned “thank you” to the closing roundtable, assuring the speakers that his life had been changed forever. As he made his way to the door, he caught my eye and asked if he could share his story with me.

“I come from the darkness, and I don’t want to go back there,” he told me. He grew up in one of the most hopeless neighborhoods of Mexico City and had run with a bad crowd. He’d ended up with a drug problem. One day, someone gave him a plant. He learned to care for it, and then to plant seeds.

“An ancient memory began to reemerge in me,” he recalls. He found himself planting more seeds, then working side-by-side with the Ecobarrios group. “I felt I had finally found my people,” he said.

“Now my reason for life is to share the things I’ve learned: how to plant a green roof, raise rabbits and ducks and bees, all these things we need to be doing to build up our food sovereignty and prepare for the great famine that comes closer each day.

“I was deeply wounded but I learned that just as the Mother Earth gives us what we need to eat, she gives us what we need to heal. And now we need to organize ourselves to defend her.”

Alberto Ruz Buenfil ecobarrios Ecovillage Movement Vision Council

Greetings

The article was excellent. I live in the U.S. and also took the Ecobarrios training in Huehuecoyotl in 2011

The reality of needed change continues to be more apparent daily but there is always much to do to create and sustain change

Give thanks for your dedication

Nyame Selassie

Delighted to receive your comment, Nyame – we are aware of your work here at The Esperanza Project and would love to know more, including how you have applied your learnings at Huehuecoyotl and elsewhere in Latin America in your own beautiful work. Please stay in touch!