2020 was a year lived in fear—fear of the surprise arrival of a novel coronavirus, of not understanding it, of getting it, of watching a loved one get it—never being sure if they’d survive. Now, with the vaccine being distributed (6.7 million doses have been given in the US as of 01/08/21), I find myself, probably like many others, daydreaming about what I’m going to do post-COVID. But that brings about a new kind of fear.

As we get closer to being free of COVID,* it seems everyone (including me, who definitely knows better) is getting ready to explode out and enjoy all the stuff we’ve been missing since the pandemic began. For me that’s mainly getting back to karate class and swimming at the Y—pretty benign, ecologically speaking. But I’m sure that’ll also mean a drive down to DC in 2021. Maybe even a flight to visit family and friends in Atlanta—adding several tons of carbon to my annual (and already excessive) emissions load. For my wife, it’ll mean a trip halfway around the world to visit her family.

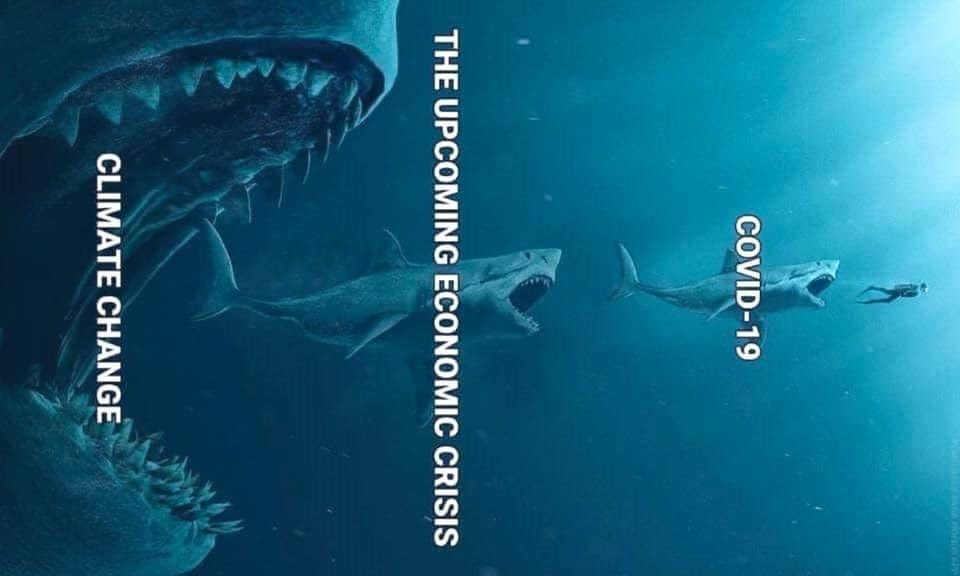

And that’s just one household. The skies will be overflowing with planes again, burning jet fuel, bringing people from one place to another, for good reasons and bad (but always rationalizable by the person traveling). The restaurants will be full, as will the shops, and everyone will be consuming at full bore, making up for lost time. And that’s terrifying (in a darker way than even COVID, albeit in a slow-burn kind of way).

The Weight of It All

Ironically, in this year of a pandemic-induced recession, for the first time in history, human stuff now weighs more than all life on Earth.** That’s right, human-made objects—mainly concrete, asphalt, metal, bricks, and plastic—now outweigh the 1.1 trillion metric tons of life on the planet.

What’s more shocking is that in 1900, just 120 years ago, our stuff added up to only 3 percent of life. And in that time, with our stuff’s mass doubling about every 20 years, we grew exponentially until today, when “the amount of new stuff being produced every week is equivalent to the average body weight of all 7.7 billion people.”

At this rate, in just 20 years, our stuff will weigh twice that of life (or more as by then we’ll inevitably displace life to a greater degree and its total mass will start shrinking). And if we fast forward another 100 years, Earth will probably look like one big sphere of plastic, metal, and stone—like you’d find in a creepy episode of Star Trek:

“What kind of species converts its home into a solid inorganic ball?” asks the captain.

“None, Captain. This must have been the work of some spacefaring parasitic creature,” replies the science officer.

“I dread discovering what lies inside,” ponders the captain [pausing for dramatic effect], “growing, transforming.”[Cue portentous music and cracking of the stone shell….]

Humans as Biofilm

As Matt Simon of WIRED noted in his treatment of this research, we’re like a biofilm eating up the entire world. And that’s true. In Underland, Robert Macfarlane, after visiting the salt tunnels under England, chats with Merlin Sheldrake, a fungi expert, about the similarities between these mines and fungi. Sheldrake describes how fungi spread out fan-like over everything, dying back and concentrating on resource rich areas to focus their consumption there—very similar to mining rich deposits, and really, to most human endeavors.

In 2020, bad luck (or more correctly, our continuing bad choices: growing too numerous, producing too much livestock, traveling prodigiously, invading untouched wilderness) finally caught up with us—and surely not for the last time—a new pandemic was unleashed. COVID was like a glass sphere that encased us, a rather aggressive slime mold. But we’re one clever biofilm. We found new ways to eat up what we could still reach, while we developed specialized slime mold tentacles to dissolve and break through the glass. The first cracks have formed—thanks to our slime mold scientists and advanced vaccine development—and soon the vaccine will allow us to fully ooze through the barrier and get on with the unmitigated digestion of our environment.

Here’s a slime mold spreading out to eat food and replicating the Tokyo railway system as the most efficient way to extract resources:

“I was so happy during this pandemic”

A few months ago, I came across a sentiment on Reddit expressing happiness for COVID’s arrival. It was confusing to hear this voiced so honestly. Essentially, the writer explained how, while not happy that people were dying or businesses were being destroyed, he was “just happy that we consumed, grinded, travelled less.” And that “Instead of working a brain-dead job, going for ‘drinks with the boss’, coming home tired I could finally work from home, work more on my garden, spend more time with my family, read books, workout, write articles.” But now with the vaccine, things will go “‘back to normal’ or what should be called “back to killing the planet.’”

The author’s final line—added later in an edit—expressed thanks for others’ supportive comments. “It’s reassuring,” he noted, “that I’m not alone in this.”

I certainly have had moments when I, too, have felt this way. Not for the lives lost, of course; this is tragic—especially as so many could have easily been prevented (and still be prevented), if we weren’t so politically polarized—but for the brief reprieve in which we could have corrected course.*** That moment when cities started building more bike lanes and sidewalks; when governments talked about tying bailout aid with environmental conditions; when we gathered in virtual sustainable consumption community webinars to explore strategies to redirect societies down more sustainable pathways.

But instead, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gas emissions increased this year (even if emissions decreased by a small degree).**** And while we flew and drove less, consumption seems to have gone down far less than expected this year. Our slime mold arms simply moved from one blocked source of consumption to another. Instead of building cars, we built refrigerators, PPE, and patio furniture.

Instead of coming together, in solidarity, we became more radicalized, fighting over such a silly issue as whether mask-wearing is a violation of one’s freedom. And instead of using this moment to better redistribute wealth, the rich got oh so much richer, with America’s 614 billionaires increasing their wealth by $931 billion (while millions lost their livelihoods, their homes, and grappled with hunger).

Of course, there is still a tiny bit of hope that this crisis can be used for good. President-elect Joe Biden may push for tax reform in the U.S. and seems to be prioritizing addressing climate change (though in a techno-centric, far less useful way than is required). The latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report is framed around using COVID recovery as a means to decarbonize the economy, and actually points out that the wealthiest 1 percent, who produce double the emissions of the poorest 50 percent of all humanity (p. XV), will need to reduce their emissions by 97 percent if we want to stabilize the climate, which also might inspire policymakers to grapple with tax reform or green recovery efforts.

But will it really? Few governments have so far supported sectors with COVID relief in ways that reduced emissions but instead sustained the status quo or even made environmental rules more lax, according to the Emissions Gap Report (p. 38). And now, people are poised to consume in a great explosion—our slime mold sex parts exploding in an orgy of consumerism after being pent up for too long. And governments, racked by new COVID-relief debt and continuing joblessness, will surely encourage that to the highest degree possible (to strengthen the economy and tax generation).

Not a hopeful place to start the New Year. But I don’t know how to sugar coat this. It’s really hard to imagine getting on the right track without radical civic action. Ah yes, that is the silver lining. With the vaccine distributed, climate change activists will be once again able to take to the streets, without fear of getting COVID, instead only having to worry about public anger and police brutality. That’s something, I guess.

Endnotes

*That is a big assumption. One that this virus may prove incorrect, through its innovative mutations. But let’s assume for the moment that, this time, with this pandemic, human ingenuity triumphs.

**Give or take 6 years and not including water, which is so full of life it could be called life, itself. But while the amount of water on the planet is huge, sadly, this expansion would shift the numbers by just 16 years.

***Again. Many in the sustainability community felt the same during the Great Recession in 2008.

****2-12 percent is the current projected reduction mentioned in the Emissions Gap Report.

Erik Assadourian is a sustainability researcher and writer, adjunct professor, game designer, homeschooling father, and Gaian.

This story was originally posted at www.gaianism.org

- The Parable of the Humane Philanthropist - January 24, 2023

- Should climate denial be illegal? - August 17, 2021

- Should we all just ‘lie flat?’ - July 13, 2021