RAPID CITY, S.D. – On Sept. 23 when Pueblo Indian U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland introduced a resolution in Congress that declares, “limiting access to broadband internet is a human rights violation,” Oglala Lakota consultant Petra Wilson drew a breath of satisfaction.

Wilson, a specialist in Indian education, had worked day and night all year to help her tribe and others qualify to become Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licensees of their own shares of the wireless spectrum.

When the FCC announced on Sept. 15 that it had approved free licensing of 157 tribal government applications to take command of rural broadband internet services, Wilson told The Esperanza Project she viewed the matter as a milestone on the way to recognition of human rights for all.

“Having access to reliable connectivity is a necessity, not a luxury anymore,” she said, adding, “It’s going to give tribes control over it.”

As a liaison between private contractors and tribal representatives, Wilson alerted and assisted officials across Indian country to take advantage of the commission’s unprecedented free offer for tribes to command much of the Educational Broadband Service in the 2.5 gigahertz (GHz) band.

For Wilson, the issue is largely about “homework inequities” affecting reservation students.”

She recalled growing up on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the 1980s and having to refer to a 1970s encyclopedia to do her school assignments, while students in far-off cities had access to a wealth of digital knowledge via computers in their classrooms.

Later, while raising her nine children in Henderson, Nevada, she worked for 15 years as an Indian education opportunities program volunteer leader in the fifth-largest U.S. public school district.

She got started when hers was among only two of 280 Native families invited who showed up at a picnic for the cause.

Admitting, “I am kind of an advocate at heart,” she lobbied for tribal self-determination and Native rural advancement, asking, “How do you work in a global context, if you’re stuck in the ’90s?”

Even in 2020, she reminds the urban dweller, the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s Prairie Wind Casino has no internet and you still have to “go up on the hill” to get a cell phone signal at many reservation spots, — should you be so fortunate as to be in possession of a functioning portable electronic device.

So, when she saw advertisements for a job opening to encourage tribal control of the radio frequencies that transmit the signals, she knew she wanted her tribe involved and successfully applied for the position of outreach coordinator, she said.

She asked her father, Oglala Sioux tribal lawyer Mario Gonzalez, if her tribe wanted to apply and immediately set to working with the administration. “Kids were an important factor, in my mind,” she said. “I wanted the kids to be able to compete.”

Soon other tribes were booking consulting sessions, so she enlisted her daughters Harmani and Halina Wilson to help her in the business.

While she was bringing tribes on board the program, she learned about many instances of what she calls “the homework gap” caused by lack of wireless connectivity in rural tribal areas. “In the majority, it’s either very expensive to access or they don’t have the ability to bring it in,” she said.

In one instance, a school received a donation of hot-spot devices but had no signal to use them. In another, the internet was so expensive that families pooled their money for one subscription and all the students went to one home to connect to it after school, she recounted.

On tribal lands, only 65 percent of the population has access to broadband, according to MuralNet, the non-profit company that contracted with Wilson. Half of tribal rural households don’t even have access to a fixed wireless internet provider, which is over twice the rate of their non-tribal counterparts, it says.

The inequity had not escaped FCC Chair Ajit Pai, who worked with the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) to create the Rural Tribal Window, affording preference to native governments in assignment of a pile of unused free licenses in the 2.5 GHz band that previously had been reserved for educational institutions.

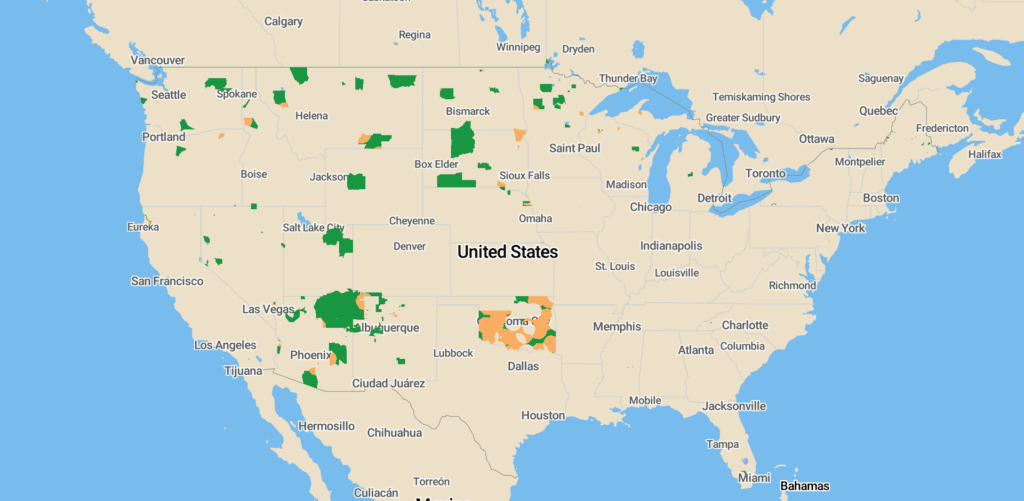

It is the single largest band of contiguous spectrum below 3 gigahertz and provides prime spectrum for next generation mobile operations, including 5G. Spectrum in this band, however, currently lies fallow across approximately one-half of the United States, primarily in rural areas, according to the FCC.

Gigahertz (1 billion Hertz), in communications technology, is a unit of electromagnetic wave frequencies based on a measure of cycles per second.

The FCC said it received more than 400 applications from tribes and their entities at the window, which opened Feb. 2 and closed Sept. 2, after NCAI requested time extensions for applications due to tribal government closures resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Pai claims his priority is to bridge the “digital divide” between the haves and the have-nots. “We must make sure that the 2.5 GHz band is used to bring advanced wireless services to those who for too long have been on the wrong side of that divide,” he told NCAI in a letter.

“As I’ve seen for myself—from the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota to the Navajo Nation in Arizona, from the Coeur D’Alene Reservation in Idaho to the Jemez and Zia Pueblos in New Mexico—the digital divide is most keenly felt in Indian Country,” he said.

“I want to make sure that those committed to connecting tribal members in rural areas are given a strong opportunity to succeed. That’s why I insisted on, and the commission included, a tribal priority filing window in our order opening the 2.5 GHz band for additional use; that early opportunity to access this spectrum will help some of the most marginalized communities in the country.”

The initiative dates back to the creation in 2011 of the Native Nations Broadband Task Force (pictured at left in a May 2020 FCC photo identified by its new name, Native Nations Communications Task Force), which involves tribal leaders nationwide, not the least of those who are Alaska Native Village representatives with eligibility to hold the licenses for the entire state.

Yet, tribes and tribal entities will have much to do in order to hold onto the 157 licenses that have received so-called quick approval to date and others that still might be approved.

First, licensees must put their spectrum to use. Two years after the license is granted, licensees must submit evidence that they are providing service coverage to 50 percent of the population in their license area.

This FCC stipulation means that 50 percent of the population in the service area must be able to access the service; it does not require a 50 percent adoption rate.

Five years after the license is granted, licensees must show that they are providing service coverage to 80 percent of the population.

Licensees may lease their spectrum, and the service provided by a lessee will be counted towards the buildout requirement.

Wilson, who is a member of the board of directors of the Indian education lobbyist organization National Johnson-O’Malley Association, predicts that achieving licensing, difficult as it was in pandemic times, is just the beginning of challenges for licensees.

“I don’t know where tribal access is going to head. It’s kind of like jumping into the deep end of a pool,” she said. “So, we will be looking at how we may help them.”

Through her limited liability corporation Tribal25, she hopes to collaborate further with the non-profit Muralnet and the Multicultural Initiative for Community Advancement (MICA) Group Cultural Resource Fund to provide continued free support to tribes.

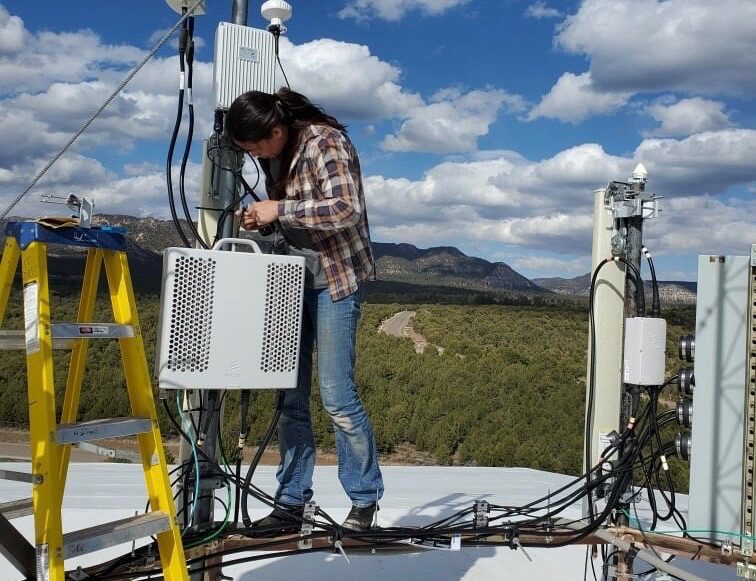

MuralNet engineer and CEO Mariel Triggs says that the 2.5 GHz spectrum is ideally and equally suited for fourth generation and fifth generation (4G and 5G) devices.

However, she said, most devices don’t yet use 5G technology and it is more expensive than 4G, so “good business sense” is to launch with 4G, which is “tried and true.”

She said, “It’s better for most tribes because 4G equipment is cheaper and because in rural areas they’re not going to be able to put up a pole every 1,000 feet,” as needed for 5G.

MuralNet notes that “broadband is the basis and future of economic development, health, and education for Native Americans.”

It is more crucial than ever now when pandemic protocols mean tribal government offices can’t operate if personnel shelter in place with no connectivity at the home, when students cannot participate in online classes, and elders can’t venture out to the doctor without risking exposure, according to MuralNet.

Haaland’s Broadband for All Resolution of 2020 aims to “to reaffirm basic civil and human rights protections so all people — especially low-income households, people of color, and those living in rural areas or on Tribal lands — can access reliable broadband internet for basic daily activities,” according to its authors.

“Everyone in this country deserves access to reliable high-speed internet, especially during a pandemic, but I’ve heard from families in my district and across the country that internet is too expensive or completely unavailable to them and the FCC hasn’t taken the right steps to connect everyone no matter their background or where they live,” Haaland said in submitting the resolution in Washington, D.C.

California Rep. Ro Khanna joined Haaland to introduce the legislation, which Haaland said, “will make sure kids don’t fall into the homework gap, workers can telework, families have access to telemedicine, and everyone can reach important information when they need it.”

The U.N. Human Rights Council passed a resolution in 2016 calling on countries to bridge the digital divide. It raised global awareness that internet is not only a luxury, but a necessity that must be protected to defend freedom of expression, freedom of speech, and basic global human rights standards since technology has become a modern global necessity, according to the authors of the Congressional bill.

“Internet blackouts have encumbered the ability of people to peacefully assemble and hampered efforts to bring transparency to crackdowns on protests in democratic countries across the world,” they noted.

“Internet access should be a human right,” said Rep. Khanna. “Despite the FCC’s mandate to increase broadband access, it has still failed to make it affordable, much less universal. That needs to change. I’m proud to co-lead the Broadband for All Resolution with Rep. Haaland to make internet access a right for every American.”

Talli Nauman is the Lakota Country correspondent for The Esperanza Project. She is a longtime Americas Program collaborator and columnist, a founder and co-director of Journalism to Raise Environmental Awareness, and Health and Environment Editor for Native Sun News Today. Contact Talli at talli.nauman(at)gmail.com.

This story was reported and produced with the generous support of the One Foundation.

- Clemency for Lakota icon Leonard Peltier called ‘moral indictment’ - January 21, 2025

- Lakota tribes, grassroots close ranks to defend Black Hills watersheds - January 21, 2024

- Native ‘hempsters’ follow global cooperative example - August 30, 2023

Deb Haaland digital divide Lakota Multicultural Initiative for Community Advancement Muralnet Native Nations Broadband Task Force Oglala Sioux Petra Wilson