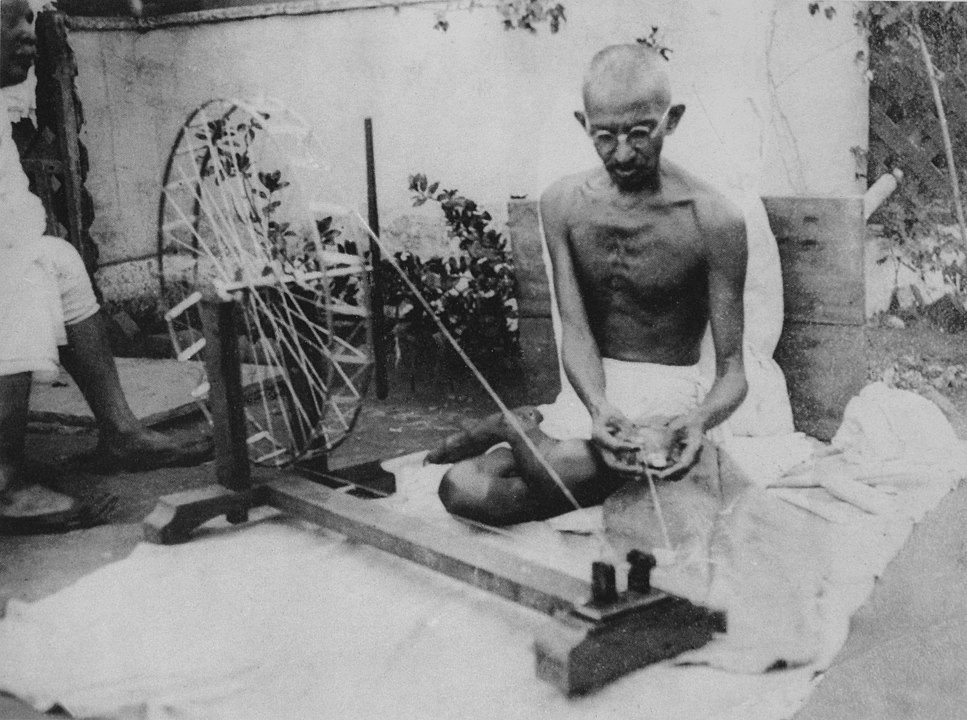

A century after Gandhi’s original Khadi Movement helped Indians to attain economic self-sufficiency and ultimately independence from Great Britain, the movement is having an unlikely revival in indigenous Zapotec communities in rural Mexico. “Khadi” means handspun cloth, and like its original Indian counterpart, Khadi Oaxaca has re-established a farm-to-garment ethic that restores dignity to its producers.

The Khadi Oaxaca project tackles some of the most difficult issues of our times, including “fast fashion” and its devastating impacts on its workers and the planet; migration; indigenous self-determination; and the scars of colonialism and neoliberalism on the social fabric of Latin America.

Leer este artículo en español aquí.

The story begins with Marcos – also known as Mark Brown, a child magician from Mexico City who traveled at the age of 14 to the traditional Zapotec village of San Sebastian Río Hondo in the mountains of Oaxaca before setting his sights on India. There he studied Eastern philosophy and ended up spending two years studying at Gandhi’s ashram with one of the Mahatma’s last surviving students.

Brown learned to spin and weave, and he returned to the village of his youth with a Gandhian spinning wheel and a passion for the Khadi philosophy. Along with his wife, Kalindi Attar, he teamed up with local families, and together they built the project from the ground up. The team worked to recover ancient practices for every step of the process: spinning, weaving, dying with traditional natural materials, designing and making the garments, and finding markets willing to pay a fair price that supports the farmers and artisans. By teaming up with an ecological Mixtec cotton-growing group called N’un Ndito (Living Earth in Mixtec), the enterprise was able to incorporate the entire supply chain.

In this interview with Marcos, we explore Gandhi’s economic teachings and the ways in which they apply to the clothing industry. For the story of how Khadi got its start, see our story in Yes! Magazine, “Spinning a lifeline in Zapotec Lands.”

I’d like to begin by asking you about the Sacred Economy teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. Can you explain the concept of Ramrajya, and tell a bit about how you have applied it in Mexico?

While in New Delhi, India, I went to the 1982 premier of the movie, Gandhi. The movie impacted me so strongly, I couldn’t sleep all night. I went and found the ashram that he had founded, and there I met an elder, Shri Dilkhush Diwanji, who had grown up with Mahatma Gandhi; he was like a Gandhi himself, in his own right.

When I met him, he was in his late 80s, and I was blessed to be able to spend four years with him. He was actually like a grandchild of Gandhi, and he became Gandhi’s right-hand man in the state of Gujarat, for the cottage industry model. And Gujarat, where his little ashram was, has one of the most successful models of Gandhian economics within the village.

Gandiji was a visionary; he saw so far into the future. He saw all this that’s going on today and much more. Few people have seen the prophetic aspects of his writings. It amazes me how little of Gandhiji’s writings have really gotten out into the public.

He wrote over 200 books. He spent a lot of time in prison – half his life almost. He said he actually kind of loved prison because that was his monastic time and he would write and write and write. There is a Gandhi library in India where you see all his work. Also in the ashram where I lived and studied he had volumes on village economics or the sacred economy and how to set it up; how to create a model. He was so brilliant — so he created these warriors, called satyagrahi – which means truth force.

The truth is that nobody in their right mind likes violence. No living being from the mineral world on up will react in a growthful way through violence. it’s the law of karma – the law of cause and effect. Clearly if we add violence even to a mineral – the stone people – there will be an effect that’s not an upward, growthful effect; it’s going to be an effect that’s unsustainable.

He taught that cause and effect — even in our thinking, of course — every thought we have is going to have an effect. We must train our minds, and we must train ourselves, in the way of nonviolence, even in the way we think. It starts from that deep understanding of bringing some level of care and compassion to our environment and the resources.

So as he would always say, when we talk about village economics, if it comes from this place of nonviolence, of a truly sacred economics, then you don’t need any commercialism; you don’t need any marketing – you don’t need to market that which has its essence and its beginning in goodness – which means nonviolence.

If you have a product that its initial impulse is out of greed or selfishness and the hoarding aspect, which is normal today – what is going to be that result? The result is a diminishing supply, and diminishing results. In other words, it’s not sustainable.

I can see how thinking of economics from that standpoint really changes things. So, in the context of Khadi Oaxaca – how have you applied those concepts there?

It starts out with the spinning wheel. If you go to a village and you want to approach sacred economics, where is the essential need? We have agriculture first – in this part of the world it’s corn, of course – then we have the fibers, the textiles. These are basically the two symbols that support the village in its old traditions.

So in the spinning – that’s what we approached through the thread, the fiber textiles —saying, let us look at the value of the thread. Gandhi would say, you have to create a thread standard. Whatever the local economy is in any vicinity of the world – the very poorest of the poor, he would always use that – I don’t really like that because we’re just looking at it economically, and they could be very wealthy in their lifestyle – but they have no capital. So that can create a destitute situation.

So the thread standard is like the gold standard used to be when in 1880, an ounce of gold would buy you a suit. And now in 2019 that same ounce of gold should be able to buy you that same suit. It doesn’t fluctuate. That’s what’s supposed to back the currency. Of course we’ve lost that now in the world – but he says that like a gold standard, we need a thread standard. We have to sit down and spin together. How long does it take to spin a kilo of thread? In village time, it’s free time – moments when they’re not taking care of the children, they’re not taking care of the fields – moments when they have time to spin. In village life, that’s how it is; in village economics, there’s no 9-5, eight hours a day job. It’s a diversity of lifestyle throughout the season, with seasonal work. So the spinning can be there for when they have free moments. But still you have to evaluate the time they have in their free moments to spin a kilo of thread.

When we started, the market was paying 400 pesos a kilo of thread – and it takes three to six weeks to spin in their free moments. This standard didn’t work; it wouldn’t support spinning. It won’t feed even two people.

The idea of a standard is that a woman can spin and actually survive on that spinning; she can make enough for her family to live on and meet their basic needs. That gives a sense of support, that gives a sense of security. And that can be freely available to all. Can you imagine that, spinning, where the standard can meet your basic needs of survival, where it takes you out of hunger? — and that gives you a sense of security and wellbeing.

So every month we would receive the thread and we advanced it from 400 pesos to 1,500 pesos; we’ve more than tripled it. When we first did that people were upset — the people who still dealt with thread. But honestly, it was almost gone in Oaxaca. Traditionally even just 20, 30 years ago, much of the thread was hand-spun in the market. But when we started in 2010, it probably wasn’t even 1 percent of the market. It had basically disappeared, because nobody’s going to spin when there’s no value.

But the mentality of our industrial complex world has labeled this thread as inferior because of its irregularities. Gandhi always said it was superior because of its irregularities. What breaks down society is its uniformality. When there’s character – and the thread is a character — it blends itself together, it finds a way to meld. And that’s the life of the village; the life of village is grounded on the character of the village, the quality of culture, the uniqueness of each village and its traditions – so we support that. It’s becoming lost, and villages are becoming generic around the world, all wearing the same clothes.

Putting the thread standard to the economics of the world today – that means it has to meet the needs of the outside world as well as the inside of the village world, and generating the money to support the needs of a family today. It’s not going to make them wealthy, obviously, but it gives them that sense of well-being and security, which is tremendously valuable in itself.

People in the village were saying to me, what are you talking about? How are you going to sell this thread? Gandhi said if you do the right thing it, in other words support the needs, that it will sell itself; it will find its market. It doesn’t mean that we don’t talk to people, write stories, go out and meet the market – of course we’ve had to do that; but it’s had an effect, it’s a miraculous thing.

It’s the ramraja point – it creates a condition, and due to that action, it finds its market – it’s amazing. I don’t know how to explain it, really, sometimes.

Gandhi says, Spinners must be karma yogis. Khadi workers are sevagram –– service to the community for self-sufficiency. There’s no violence from the very beginning. When the cotton is grown it’s through companion planting, the way they did in the old ways, small plots, no pesticides.

We’re bringing back the prehispanic heirloom cotton seed, together with the coastal cotton project — whose co-founder Margaret MacSems ended up later joining the Khadi Oaxaca team. The native people of the coast traditionally always planted it amongst the corn, the squash, the beans, the marigolds – they planted it in the milpa, the traditional cornfield.

Cotton when it’s planted as a monocrop invites pests, plague – even in somewhat small plots. So that’s why cotton today is the most toxic crop in the world, and thousands of people in the world die every year from cotton farming in India alone – and that’s not an exaggeration. They don’t have regulations because it’s not a food crop, so the amount of pesticides and herbicides they use is phenomenal. And the whole GMO thing is just a nightmare.

So we take that cotton and we disperse that. We are working with about 40 growers right now. But instead of large plots, it’s small plots, many hands. It’s a supplemental income.

And it starts with the seed.

People say, you guys are nuts — you’re growing your cotton like farm to table – but it’s from farm to your wardrobe, your closet.

And are the growers also the spinners? Or how does that work?

Some of the growers are spinning, but most are not, and so we bring the cotton from the coast, which is about five to six hours from San Sebastian, for the spinning and the dying and the weaving and everything.

That’s cotton. The wool is a whole other thing. This used to be a sheep and wool production place; that was one of the main industries here, but it’s nearly died out. So we have reintroduced sheep under a Sheep is Life project, and we spin our own wool thread, too — but that’s a whole topic in itself.

Toward the end of Gandhiji’s life, people asked him, “How do you think the world has changed with your work?”

He said, “My life has been an experiment, and I failed miserably. Hopefully future generations will wake up to the experiment and learn from it.”

He didn’t want the partition of Pakistan and India and Bangladesh. He said, “I don’t accept partition – we as Indians are not yet mature enough to govern ourselves.” When the British left and Indians created their own parliament, Gandhi wasn’t invited to sit on the parliament – they basically instilled the same form of government as Britain – it was a complete failure for Gandhi. He did not want centralized government; he wanted decentralized government; he wanted the villages to be autonomous.

Of course, he was shot because he was trying to stop all that.

But his experiment is a shining light for us to see a way out of the crisis we are in today. And to say that we’ve affected a change in this village – saying the village has shifted to going back to a sustainable way of life – I would say we’ve affected change to the degree that hundreds of people are thinking about it when they’re working.

Has Khadi Oaxaca had an impact on the immigration problem?

We’ve definitely helped to reduce migration. More than half the people who are weaving have told me, “I was going to leave, but now I’m weaving, and I’m really happy weaving. It’s wonderful, we don’t have to go elsewhere to make money. I see that we can comfortably sustain ourselves here.” So that is good. We want to be a model so people can see this has got the potential to be so big. We’re helping to create an alternative.

Bringing it down to the micro level, I see a future in the campesino life, the ranching life. Here we have what’s called rancherías – that’s what really supports the pueblos. Everyone used to live on the rancherías, because that’s where life is. That’s where they grow their food, and raise their animals, and have their homes and their natural resources – when I first came here, people who lived on the ranchería, they didn’t touch money; it wasn’t even an issue hardly.

I see our future there. I see the future for generations to come there. There are still people who live on the rancherías. A ranchería is from eight to 15 families that live in a big valley and have maybe 30 or 40 acres per family, neighboring one another. And they all support each other, so that when they go to till the field, it’s not one family that goes to till the field. Several families will come together with a pair of oxen and plow the field together and plant it together and clean and harvest it together –and this creates an abundance of corn that they can live on. It doesn’t work as individual families, it’s a collective.

They still have a certain amount of capital need. They can take the spinning wheel and they can raise the sheep or they can receive the cotton, and spin on the ranch. And for them, 100 pesos is a lot – the value of a peso is a very different thing than what it is in the city.

That is what we try to instill in our education. If they want to spin, we tell them, this is a work in progress and it’s not easy – if you’re spinning or weaving, and you’re working with Khadi and your family is not growing corn, we’d rather you would go grow corn. If you’re doing this just for the economic aspect, then you’re missing the point.

So this is really about supporting the rural agricultural lifestyle.

Yes, it’s about supporting an animal husbandry lifestyle – that’s the three aspects to it; animal husbandry, agriculture and textiles. They support one another.

I was reading in the article that you shared with me, the idea that Europe and the US have converted so completely to homogenized systems that it may be impossible to go back – but the other type of economy is still alive in India. Is it still alive in Mexico as well?

Yes.

So in Mexico would you say that it’s perhaps a better environment to create this type of economy than in the United States?

It’s very difficult in the United States – that is the challenge. Gandhiji said the First World has become so homogenized I don’t know if there’s a possibility of returning. How do you find a thread standard — that baseline to grow off of – can you imagine what a thread standard would be in the US? If it’s $80 here per kilo – in the US, maybe we have some homesteaders there – if we had to create a thread standard there, it would be like $600 a kilo or something because of the economic situation there. So it shows you the bubble – how far away we’ve gotten from our roots – the industry has taken us so far away.

You can’t just raise a couple of cows – you think, well I’m not going to make a living with a couple of cows. No, but the cows subsidize the rest of it. But in the modern world, you have to raise a couple hundred cows to get anywhere. Because there’s no meeting of the modern industrial world with the village economics of a sustainable lifestyle. They’re so far apart.

But yet in Mexico you can still meet that, in India you can still meet that, because they’re poorer countries – they’re not that far out on the bubble – in the rural, very rural areas. Because in the modern areas of India and Mexico they’ve gone way out into the bubble like in the First World, and there’s no meeting it. But in the rural, rural areas, they’re still poor enough – which is their saving grace, in one sense.

So you’re saying that their poverty has saved them, in a way.

Yes! Because if you went out to most of the really rural ranches, most of them who haven’t received, let’s say, Khadi philosophy, most of them if you gave them the money they’d hop onto the modern bandwagon overnight. Because we’ve been hypnotized, we’ve been delusionized with the glitter of modernization. And they think it’s a better life and it’s through generations and generations of conditioning in an educational system of competitiveness, and I have to work for me and mine to get ahead.

Individualism, basically.

Individual consumerism. Gandhi taught that education begins with the collective community, right? We’re part of a collective community to support one another, and we do that by giving to one another. That’s the Ramarajya Basics, 101. Because you see in the difference of the educational system.

So that brings me back to the question: how would this model be relevant to people in the United States? Can the lessons be applied in the modern world?

This is one of my biggest challenges, and here’s how I’m looking at it. Because right now, I’ve been literally in the rural, rural back areas of Oaxaca, here in the Sierra Madre in the ranches – and this is our salvation — between you and me, when the shit hits the fan, this is the place where there might be some chance of survival. And this is what I want to work towards in making a model for the world to see. How can that model be applied to somewhere like the US?

We’ve been going to France – and France is very similar but because of its long traditions it’s maintained a certain value on rural life. How can we bring it into actual engagement within the marketplace of a capitalist world like the United States?

Well, to start with, how do we shift what is a sense of cause and effect in the way that we think of it? How do we get out of that mentality and realize we are here to serve our community at the local level? It’s happening right now in the sense that we’re realizing that we need to have food that is healthy – the community gardens that are happening, for example. The food revolution has had a lot of advancement in particular areas in the United States. But we haven’t seen a garment revolution really yet. We have the slow food movement, we have the local food movement, we have the community gardens – but our clothing industry is the second most toxic industry in the world today. You have 6 billion people buying fast fashion, and those clothes are deadly from the start. So many of us are aware of that, but we’re not doing anything about it.

Tell me more about that. What do you mean when you say “fast fashion?”

They say if they stopped manufacturing clothing on the Earth right now, we would have enough to last us for 30 years; we don’t need to manufacture any more clothes. We have enough to clothe the planet; there’s mountains and mountains of clothes — but these clothes are toxic; they don’t even know what to do with it. They can’t burn it, they can’t bury it –and we’re putting this on our bodies – and we don’t understand that these microfibers will go into your blood and contaminate you. Gandhiji even spoke about these molecular fibers of the polyesters, the synthetic clothing. They will go into your water and your air and contaminate you – they’re everywhere. So on the level of the First World,– it’s got to be a wakeup movement – and we have to bring civil disobedience to the industry. We have to say, no more. I will not buy this.

People say we can buy secondhand, but that’s not the answer either. Because we want to make a statement; we want to create a movement. And by wearing handspun, handwoven, nonviolent clothing, you’re making a very strong fashion statement.

I suppose that’s one place where this touches the First World; because people can support these kinds of initiatives by buying these kinds of clothes.

That’s a very good point; it’s very important to understand the true cost of clothing – we say this is the true cost, because we have a thread standard that supports the poorest of the poor in these economies that have been manipulated and subjugated and enslaved – they have been literally robbed of their assets. Now we can say – no, they can spin and we’re going to support them through a standard of their local economy that actually allows them to have a decent and dignified life.

You say these clothes are expensive but in actuality it’s the true cost. What’s really expensive is the modern clothing — because if you looked at the true cost of the lives it takes, the pollution and the toxicity that it creates, how do you evaluate that cost? That cost is exceedingly more expensive than the so-called expensive handmade clothing.

These points are very important for people to come to understand — that we don’t need 30 shirts. We can well make do with a lot less clothing, and our clothing could have true value.

What is true value? What you wear is how you communicate to the world, believe it or not. Are you communicating industrial pollution? Are you communicating slave labor? Are you communicating that that’s ok with you? That you’re supporting this clothing industry that’s lobbying your government… but I don’t want to go into politics. But I think you see the point.

Each thread communicates – whether it’s a mechanized thread or it’s handmade – those are the first fiber optics. When that thread is being made, it receives an energy to it, it receives a communication power, an ability. You’re communicating the essence of that thread, and what it is about.

In England they say, the suit makes the man. What you wear is what you are, the same as what you eat. We’ve lost that understanding. The Old World knew that the beautiful clothing they would weave spoke of who we are, of the traditions; our life history is in our clothes.

So today we’re speaking that we’re industrial polluters to one another. Is that what you want to stand for? I think we’re on the threshold of a new clothing revolution, slow fashion, true cost of clothing – these are the new buzzwords.

The garments are truly beautiful, and I’m glad to hear that they are gaining a following. Can you talk to me a bit about your plans to take this project to the next level?

We’ve been going for some time in the summers to Thich Nhat Hanh’s community, Plum Village, in France. And one of the things that motivates and excites me to be there is that the monks want to spin their own robes; that’s one. And two, they are very interested in expanding the global village idea there, and in reaching out to villages in different parts of the world, like Vietnam, and India, and Indonesia, which is right on target with what Gandhi was saying about the return to the village way of life.

The long-term idea would be to have an international Khadi Center in France. And Plum Village attracts very educated and career-minded people — and a lot of people in the fashion industry get so fed up with it. So I can imagine a wonderful possibility of an expanded movement.

And what we’re doing in Oaxaca, on a smaller scale — we have acquired a place in Oaxaca City and we want to create a Khadi Center there, that will expand out to various villages within the state of Oaxaca.

So we started on the ranches and the village of San Sebastian Rio Hondo, and now we’re pretty established in the area; and we’re expanding now to the Oaxaca City center, to reach out to other villages using the same model; and then looking toward France to be an international model hub for Khadi, supporting the village way of life.

Yes – and how wonderful to bring Gandhi’s vision together with that of Thich Nhat Hanh.

Thich Nhat Hanh was very inspired by Gandhi – that’s why he called it Plum Village. He wanted to see a village; he wanted to see the nuns and the monks interact with the village in the context of the village lifestyle. So they’re very excited about us and we’re very excited about them.

I can see this becoming very big and becoming a really impactful movement.

Stay tuned for more inspiring stories from the Khadi Oaxaca team, and to read the story about Khadi Oaxaca that will published soon in Yes! Magazine. Learn more about Khadi Oaxaca or purchase their clothing on their web page, or follow them on Instagram or Facebook.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

ecofashion ethical fashion Kalindi Attar Khadi movement Khadi Oaxaca Marcos Brown Mohandas Gandhi satyagrahi sustainable fashion

Awesome! I love this so much. Thank you Tracy for telling us about this. Truly inspiring!

Dear Friends I am so happy to hear about this. YOU ARE SO VERY BEAUTIFUL. I wish I was part of your world.

Thank you so much Janice how inspiring. We named our craft business “Swadeshi” in honor of Gandhi’s spinning wheel program, must be the same.

THEY HAVE BEEN TRULY INSPIRING ALONG ALL THESE YEARS… LONG LIVE

¡Qué rico tejido! I live in Oaxaca City and would love to wear these clothes to show support of this beautiful area and its native people. Restoring traditional fabric and clothing is so important, and Oaxaca has such a rich tradition, so worth preserving. I would like to know where their Oaxaca City store will be so I can visit (when the pandemic situation eases enough to make it safe, of course). In the meantime, and for others who don’t live in Oaxaca, their web site comes up with a simple search for “Khadi Oaxaca”. Can’t wait to be able to order online!

Wonderfull story and initiative. I wish the project well. I have been a fan of various types of Khadhi since I first went to India in 76, including ahimsa madkha silk.

Funilly enough when I saw ‘Gandhi’ in Delhi when it came out I was the only westerner in the cinema and was wearing khadhi trousers, shirt and shawl. Then while exiting the cinema I noticed all the Indian viewers emotional from watching the movie, were wearing industrial factory made cloth, much of it synthetic. They saw me a foriegner dressed in my full Khadhi out fit and for a moment I think they felt a tinge of embarassment of how the nation had totally regaled on Gandhi’s ideas of village self sufficiency and went full head for industrialisation of the economy.

Dear Kalindi, Marcos and Leila,

Your achievements with Khadi Oaxaca are truly inspiring! In a world where harmony, respect, generosity and love can often seem in short supply, your proof of their presence and success is nourishment to hearts and minds who hope for a kinder, more abundant life for all. You and your local village friends and partners demonstrate the power of community, the unstoppable force for good it can become. Together you prove that the touted impossible is not only possible, but accomplished. May the world see your example and dare to follow it. With love, Sharron

My best wishes to Khadi Oaxaca. I came to know of you through Modi’s twitter post. I wear Khadi with mixed response from the public. Most people admire the garments I wear, but some people are plainly intolerant, and ask why I am wearing un-American clothing!