Author, public speaker and self-described “Emergency Planetary Technician” Albert Bates is a master at drawing wisdom from a vast variety of sources. Recently he drew my attention to this excellent column that he penned last year, drawing on the great Sauk leader Black Hawk to help us envision one possible outcome from our current climate crisis that is anything but apocalyptic — but one that will require enormous wisdom and skill to achieve. Calling on our leaders to channel Black Hawk — and read Albert Bates, who is a featured speaker today in the 10-day Communities for Future Online Summit. Tune in to his talk — free for today only — right here.

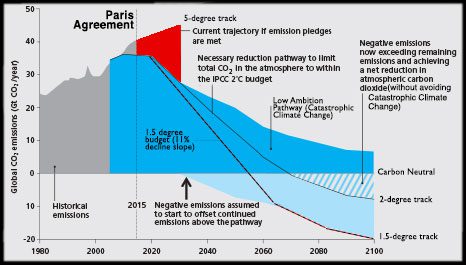

The October 2018 United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on the Paris Agreement 1.5 degree target said, owing to our procrastination, human society will need to go on a near-starvation diet of fossil fuels and to decarbonize the global economy, taking a glide path for industrial civilization with an angle downward of approximately 11 percent per year in order to halve production of anthropogenic greenhouse gases every 7 years for the remainder of the century.

Trying to imagine this is like picturing the surprise of a pilot at the controls of a 737-MAX when his flight computer takes over and pitches the plane into an uncorrectable 11% dive.

By 2050, we need to be at or close to zero emissions, IPCC says. And that will not be enough.

Because we exceeded then-considered safe concentrations for warming the planet in the late 1980s to early 1990s when we crossed the 350 ppm CO2 boundary, we will need to keep reducing for an extended period after we pass zero emissions. We have to remove the legacy emissions we generated while delaying. We have to stay on the decline slope until we bring back the natural carbon equilibrium of the oceans and arrest whatever tipping points have already tipped. We can’t rebuild the ice at the poles or put back melted glaciers but we can restore the atmosphere and oceans to something more closely resembling conditions before Col. Drake first raised oil from the ground in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1864. That is our current mandate.

The alternative is near term human extinction.

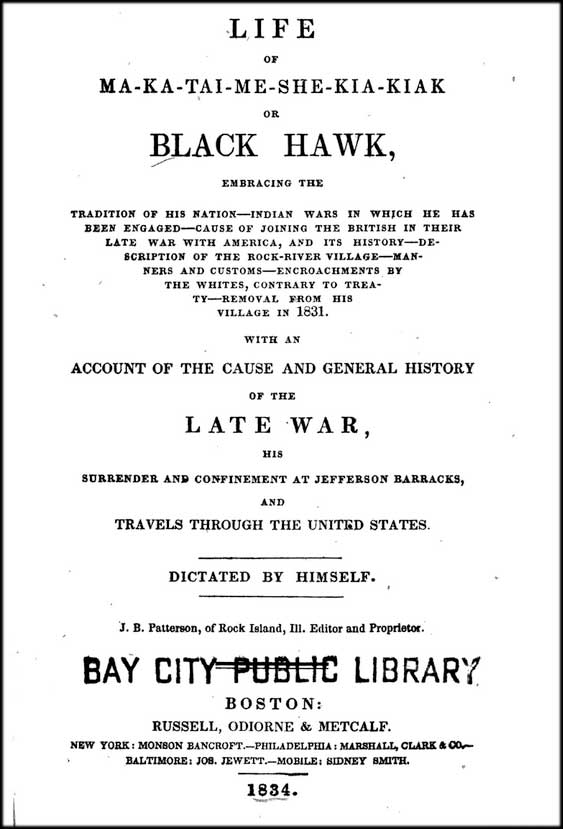

My readings this week pursued a different context, but the curious mind being what it is, connections were made and so now we come back around full circle. I read Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk, Embracing the Traditions of his Nation published in 1833, 5 years before the author expired at age 70 or 71. Among the stories the great Sauk chief related was how his people had lived in the Mississippi Valley in the centuries before Europeans arrived.

In previous columns we spoke of surfer lifestyles as a way to decouple production and consumption. This week we can look at how indigenous peoples in North America created a steady-state human economy that harmonized with natural limits for tens of thousands of years or longer. They built a model sustainable society, with some features we may find abhorrent and others we could value, but whose ultimate proof of fitness for purpose is that it sustained not only the two-leggeds but soils, forests, lakes, rivers, and bounteous biodiversity, some megafauna losses notwithstanding.

Black Hawk describes the annual cycle of life for his village:

Here we found that troops had arrived to build a fort at Rock Island… we were very sorry, as this was the best island on the Mississippi, and had long been the resort of our young people during the summer. It was our garden (like the white people have near to their big villages) which supplied us with strawberries, blackberries, gooseberries, plums, apples, and nuts of different kinds; and its waters supplied us with fine fish, being situated in the rapids of the river. In my early life, I spent many happy days on this island.

Our village was situated on the north side of Rock River, at the foot of its rapids, and on the point of land between Rock River and the Mississippi. In its front, a prairie extended to the bank of the Mississippi; and in our rear, a continued bluff, gently ascending from the prairie. On the side of this bluff we had our corn fields, extending about two miles up, running parallel with the Mississippi; where we joined those of the Foxes, whose village was on the bank of the Mississippi, opposite the lower end of Rock Island, and three miles distant from ours. We had about eight hundred acres in cultivation, including what we had on the islands of Rock River. The land around our village, uncultivated, was covered with bluegrass, which made excellent pasture for our horses. Several fine springs broke out of the bluff nearby, from which we were supplied with good water. The rapids of Rock River furnished us with an abundance of excellent fish, and the land, being good, never failed to produce good crops of corn, beans, pumpkins, and squashes. We always had plenty — our children never cried with hunger, nor our people were ever in want. Here our village had stood for more than a hundred years, during all which time we were the undisputed possessors of the valley of the Mississippi, from the Ouisconsin to the Portage des Sioux, near the mouth of the Missouri, being about seven hundred miles in length.

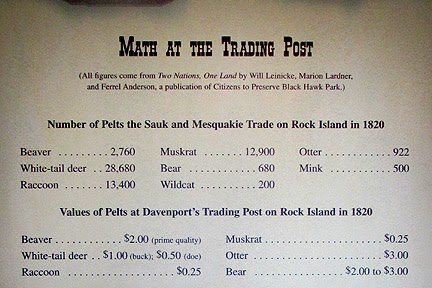

When we returned to our village in the Spring from our wintering grounds, we would finish trading with our traders, who always followed us to our village. We purposely kept some of our fine furs for this trade; and, as there was great competition among them, who should get these skins…. When this was ended, the next thing to be done was to bury our dead, such as had died during the winter. This is a great medicine feast. The relations of those who have died give all the goods they have purchased as presents to their friends — thereby reducing themselves to poverty, to show the Great Spirit that they are humble, so that he will take pity on them. We would next open the caches and take out corn and other provisions, which had been put up in the Fall, and then commence repairing our lodges. As soon as this is accomplished, we repair the fences around our fields, and clean them off, ready for planting corn.

+++

The crane dance often lasts two or three days. When this is over, we feast again and have our national dance. The large square in the village is swept and prepared for the purpose. The chiefs and old warriors take seats on mats which have been spread at the upper end of the square, the drummers and singers come next, and the braves and women form the sides, leaving a large space in the middle. The drums beat, and the singers commence. … What pleasure it is to an old warrior, to see his son come forward and relate his exploits — it makes him feel young, and induces him to enter the square, and “fight his battles o’er again.”

When our national dance is over — our corn fields hoed, and every weed dug up, and our corn about knee-high, all our young men would start in a direction towards sundown [across the Mississippi River into Iowa], to hunt deer and buffalo — being prepared, also, to kill Sioux, if any are found on our hunting grounds — a part of our old men and women to the lead mines to make lead — and the remainder of our people start to fish, and get mat stuff. Everyone leaves the village and remains about forty days. They then return: the hunting party bringing in dried buffalo and deer meat, and some times Sioux scalps, when they are found trespassing on our hunting grounds. At other times they are met by a party of Sioux too strong for them and are driven in. If the Sioux have killed the Sauks last, they expect to be retaliated upon and will fly before them, and vice versa. Each party knows that the other has a right to retaliate, which induces those who have killed last to give way before their enemy — as neither wish to strike, except to avenge the death of their relatives. All our wars are declared by the relatives of those killed; or by aggressions upon our hunting grounds.

The part about returning with Sioux scalps may seem barbaric to our sensibilities but if we can step back and see what that process was about, it was really resource stewardship. Black Hawk says elsewhere in his narrative that the Creator placed the nations in their particular places but in actuality these bioregional borders were fluid. Changing climate and other factors brought about migrations. Nations patrolled their borders to keep out poachers and to protect their own winter provisions. Within their hunting range, they secured the balance of predators and prey. The Sioux were plains nations, horseback buffalo hunters. They were kept from expanding into the forests of the Sauk, Fox, and Iowans only by vigilance. Between the Sauk, Fox, and Iowans, there was a tenuous truce that permitted shared hunting grounds and provided for retribution when offenses were committed.

It might be noted that Black Hawk says they had lived on the Rock River for one hundred years. Indeed, the Sauk only arrived to the area in the 1730s, following the Second Fox War. During that conflict, occasioned by the Fox resisting being made French slaves (more than 1000 were held as slaves in New France) the French and their Huron allies pursued destruction of the Fox to such an extent that what had been one of the largest, most powerful and wealthiest nations in North America was nearly extinguished. The destruction of the Fox allowed the Sauk to settle where today is the Illinois Quad Cities.

Black Hawk relates the story of a young brave who killed an Iowan. To keep the peace, he orders the brave to present himself to the Iowan village and surrender his life. The brave is overwhelmed with sickness, and his brother steps forward to go in his place. At the Iowan village, although the young braves taunt and want to kill the boy, the elders learn this story and decide to pardon the brother, sending him back to the Sauk with horses and corn. Black Hawk says the Sauk always respected the Iowans for their mercy and honor on that occasion.

We find it difficult to imagine fitting the population of Moline into the lodges of the Sauk, Fox and Iowans and sustaining it on fish, corn, squash, beans, bear meat and dried venison. And yet, that is what 11% implies.

These lives may seem overly simple to us, to the point of being boring, or brutish. If we look at Quad Cities Illinois today, the Rock River running through, Moline city limits separated from Davenport Iowa by Rock Island in the middle of the Mississippi, we find it difficult to imagine fitting that population into the lodges of the Sauk, Fox, and Iowans and sustaining it on fish, corn, squash, beans, bear meat and dried venison.

And yet, that is what 11% may imply. When we take an 11% per year decline slope out past negative 100%, and negative 200%, we take ourselves back to something more closely resembling the ways of our ancestors before the steam engine.

What I confirmed by reading Black Hawk’s account is the same as we might learn from any number of anthropology studies; that voluntary simplicity and gift economies provide for all, allow ample time for leisure, celebration, and sport, foster honesty and integrity as the highest social values, and encourage exploration of natural spiritual powers through deep observation, revelation, and clairvoyant dreaming. It is no worse than the lives we live now and in many ways better. This is why in the history of the American colonies, those who switched sides and became Indians remained so, while Indians who tried out Western Civilization usually lasted only a short time in their strange surroundings before returning home.

Most of us likely cannot conceive of how a society as complex and populous as modern techno-consumer culture could transition in a century or less to something resembling Black Hawk’s village. We take half measures, like installing renewable energy, supporting a Green New Deal or joining Transition Towns, which are steps along the path, but not nearly enough to get where we must go. Next week we will have a look at David Holmgren’s latest missive, the strategies of the Global Ecovillage Network and Ecosystem Restoration Camps, and how to adopt the most realistic patterns of living that can be sustained into a fragile, hazardous and uncertain future.

In an Esquire interview, 2020 presidential candidate and mayor of South Bend Indiana Pete Buttigieg was asked, “Would you support reparations to compensate for America’s history of slavery?” He replied:

I’ve never seen a specific, workable proposal. But what I do think is convincing is the idea that we have to be intentional about addressing or reversing harms and inequities that didn’t just happen on their own.

In the aftermath of the superfloods striking the former domains of the Sioux, Iowans, Fox and Sauk, one policy that might be worth considering is rather than spend billions of fiat currency to compensate farmers for losses and rebuild an unnatural economy there, to simply buy up all that river bottom land and give it back to the Nations still in exile in Oklahoma. Let their young people who want to do it rebuild a model that was once and for a very long time regenerative by design and could be again.

Go take a sister, then, by the hand

Lead her away from this foreign land

Far away, where we might laugh again

We are leaving, you don’t need us

— Crosby, Stills and Kantner, Wooden Ships (1968)

Albert Bates is an author, public speaker and self-described “Emergency Planetary Technician.” He is founder of the Global Village Institute for Appropriate Technology and a longtime climate science, permaculture and ecovillage educator. Follow him on Blogger and Facebook or Twitter. His Patreon donations help him fund his advocacy work as an urgently important voice in the global climate change discourse; you can also support his work through PayPal at [email protected].His most recent book, Burn: Using Fire to Cool the Earth (Chelsea Green Publishing, Feb. 2019) is a game-changer. Donors to his upcoming book, PowerUp!, get an autographed copy off the first press run.

- Black Hawk’s 11 Percent Solution - February 4, 2020

1.5 degree target 11 percent solution Albert Bates Black Hawk IPCC report Paris agreement Rock Island Sauk