In these abundant days of autumn as we come together to celebrate family, food and a tradition that is largely fiction, many of us have been delving into deeper truths about our nation – because we are ready, because those who hold those histories are ready, and because it’s time.

Diné/Cheyenne/European American scholar, musician and activist Lyla June is one of those truth-tellers who has been researching the past from an indigenous perspective, and who has worked very hard to cultivate an attitude of love and forgiveness. We share her eye-opening Thanksgiving origin story, told from the Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where our forebears began a colonization process that would devastate and very nearly obliterate the civilization that gave them the keys to survival in these lands.

Greetings my kin, my people. I am here at the Plimoth Plantation colony where the separatists, as we now call them Pilgrims, first made their landing, and where they set up their settlement. And so we’re here today and we’re wanting to talk about the truth of Thanksgiving because we believe that truth is what’s going to set this country free. It’s really hard to look at the truth of this country, but I want to invite you to be brave right now. I want to invite you to take a little walk with me through time, and also to explore the notion of forgiveness and how we might all heal from this really hard past. And so I think it’s really important to tell the truth here today because while yes, Thanksgiving is a very important part of American social life, it is actually founded on a lot of untruths.

And so I’m really happy to come here today to talk about some of those untruths and to really set the record straight about Thanksgiving. You know, during the time that we talk about Squanto coming and helping the pilgrims and healing them and helping them understand how to plant food, how to survive on the land, he was also being kidnapped and sold into slavery in Europe only to come back here, and to find his entire nation completely obliterated by smallpox. So this man who gave a lot of compassion to people ended up getting sold into slavery.

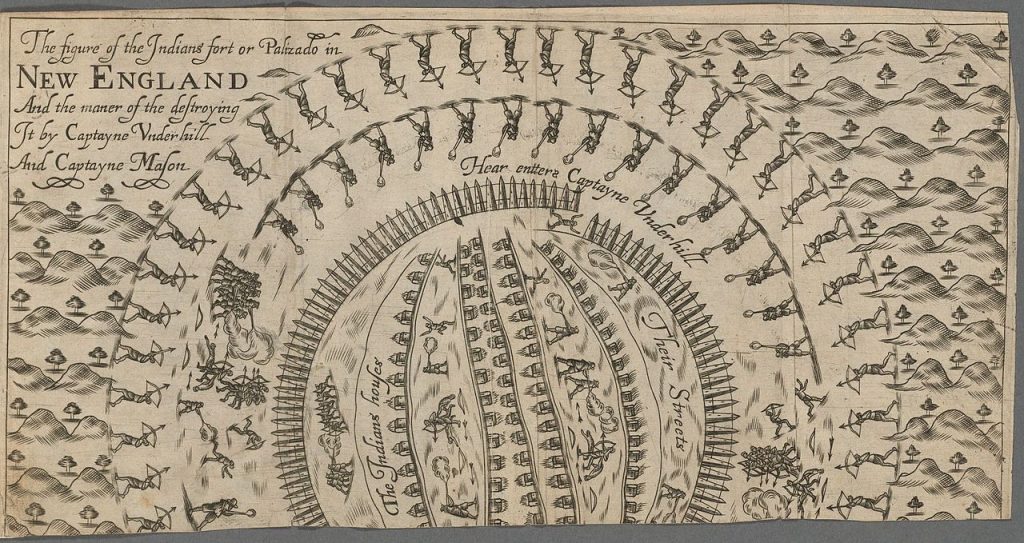

A really important thing too, is that in 1637, when you have the governor of the Massachusetts colony, John Winthrop — this is only 16 years after the supposed Pilgrim feast with the native people — he declared the first day of Thanksgiving, but it wasn’t for what we think it was. It was actually after the massacre of hundreds of Pequot people down in Connecticut. And the Thanksgiving feast was to thank God that all of his soldiers had returned from this massacre. They massacred hundreds of Pequot men, women, and children. So we have to understand that the colonies here in Massachusetts were not peaceful. They were colonial. They were fearful and they were aggressive and they harmed many, many, many indigenous peoples. And that’s really, really important for us to understand so that we don’t rose-tint the history that we stand on.

And so I think it’s really important, and it’s really similar to Pocahontas; because in the Disney movie, they talk about this beautiful woman who met John Smith, this beautiful man, and they fell in love and everything was great. But the real truth is Pocahontas was a child when she was married to an Englishman and had no choice in the matter, was shipped to England and died in England of disease.

If the Pocahontas story were true, that would be great. I actually liked that movie. But the fact is we’re not telling the truth. We’re not telling what actually happened. And this is a problem because we’re trying to evade our mistakes. So we have to understand that Thanksgiving, as we know it, was contrived during the Lincoln administration during a time of great civil unrest. He needed something, some kind of event to bring us all together into a single national identity. But we have him saying, ‘Oh, the pilgrims and the Indians just had a peaceful dinner and it was all wonderful.’ (Public domain image of Pocahontas: Clarke, Mary Cowden (1883). World Noted Women. New York: D. Appleton and Company.)

And not only is that not true — there was a lot of violence around that time — but also Abraham Lincoln was saying this as during his administration, the largest mass execution in this country happened and it was of 38 Dakota indigenous peoples. And Abraham Lincoln also oversaw the incarceration of thousands of Diné people, my ancestors, outside of Albuquerque, a concentration camp that Hitler would later study for his own because it was so effective at dehumanizing the people.

This story is one of several with Lyla June and is part of a larger series with the Women of Standing Rock.

Thanksgiving for indigenous peoples is a daily ritual, a daily act. Because in the morning we give our offerings to Creator, thanking Creator for life. And it’s not a single day of the year, but it happens every single day of our lives; it’s the gratitude that we have for life and for living. So this is really important to know about Thanksgiving and to understand that no, it’s not oh, everyone was happy and they ate together and kumbaya, but rather the indigenous peoples were in an incredibly hostile situation where they were raided, sold to slavery and massacred.

And so that comes to my next point, which is forgiveness. I’ve been forgiven big time in my life and I’ve been through lots of horrible stuff growing up as a child and therefore I did lots of horrible stuff to other people. What happened to me as a child where I got hurt and confused and abused and then went on to hurt and confuse and abuse others is similar to the white colonists, to the European invaders, because they had been hurt and abused; in their homeland, for example, they had the Roman expansion. They had the Inquisition, they had the destruction of millions of women who were persecuted as witches. They have a complete obliteration of their culture. You have the Welsh language being illegalized and prohibited in schools. You have the colonization of the indigenous peoples of Europe. And as my elder Phil Lane Jr. says: Hurt people, hurt people; and colonized people, colonize people.

And so when I think of it this way, and even though people say I’m crazy, I step on this land with a lot of forgiveness. I look to these colonist homes here and I really have a lot of forgiveness for them. We have the opportunity as indigenous peoples to forgive and to send love to those who sent us hate. And to say, “I love you” to an institution and a wave of an ideology that nearly annihilated us from the face of the planet.

And I think forgiveness is a beautiful thing because it releases us all from the cycles of violence that we’re in. Because if we forgive the people who perpetuated these things, we can actually feel grace. And when people feel grace, people understand the type of love that Native people were all about. They can feel it in their whole being, and that grace can transform so many situations into beauty.

And so I’m really, really advocating forgiveness and even standing on this land where I know indigenous peoples were massacred, where I know indigenous peoples were destroyed, where I know they were evaporated to thin air by disease—I want to extend forgiveness to John Winthrop, the man who ordered the slaughter of Pequot nations. I want to extend forgiveness to him and tell him that I’m praying for him, wherever his spirit is, and I love him, and everything is going to be okay. And through that forgiveness, I think we can evolve and become a healthier nation. And through forgiveness, more truth comes out, right? Because we don’t talk about truth unless we’re feeling safe to talk about it. But if we come and say: “Listen, we’re sorry that you got colonized. We’re sorry that what happened to your people in your continent that made you so downtrodden, so afraid, so unhuman that you would come over here and harm others. We’re sorry for what happened to you and your ancestors. We’re sorry.” That releases a lot of pain for a lot of people.

And so we’re in a time now where we can stop perpetuating the legacy of colonization. We’re in a time now where we can actually change things for the better, and we can take the truth of the bloody history of this country and we can turn it into action to change the legacy of the shadow of colonization. And so that’s exactly what Plimoth Plantation is doing here. I’ve been speaking with the staff and I find it incredibly beautiful that the museum here has officially changed Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day. The staff here is working with a lot of indigenous staff who work here to talk about Native American stereotypes and to talk about history from their angle. And the people who work here are indigenous peoples.

And a lot of the people here who are learning about this place are learning it from indigenous voices themselves, face to face, in person. And so I think that this is just one example of how we can alter who we are and become brave to look at the truth.

And just as Gandhi said, he believed that we could solve the whole world’s problems with truth and love. And he followed the principle of Satyagraha, which was a mixture of truth and love. And so we are here to bring out the dirty laundry and look at it and air it out. And in the face of that cruelty, in the face of those massacres, in the face of that genocide, to come here with love and to forgive.

And I believe that’s what we can do as not a nation of America, but as a nation of Turtle Island, this whole continent, we can heal. We can come together and we can fix this.

Follow Lyla June on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or YouTube; check out her website here; and sign up for her Medicine Theory courses here.

Thanks to videographer Bill Hurley and The Extended Play Sessions for this collaboration.

- Fast for the Future - January 20, 2020

- Lyla June candidacy takes aim at addiction to fossil fuels - December 13, 2019

- Lyla June on The Truth of Thanksgiving - November 26, 2019

Bill Hurley Extended Play Sessions First Thanksgiving indigenous history Lyla June Pequot Plimoth Plantation The Pilgrims Wampanoag Nation Women of Standing Rock