Betsy Greer is one of the most unassuming people you’ll ever meet. She’s much more interested in promoting other peoples’ work than her own. Still, her impact, as the one who first popularized the concept of craftivism, has crossed continents and changed lives. As a sociologist, her approach has been one of intellectual curiosity combined with a broad view of activism.

Tracy: I saw that you majored in sociology and did your dissertation on knitting and DIY culture. How did you first hit upon the idea of combining craft and social change work?

Betsy: I came across it as a sociological project. My grandmother knits so I knew what it was like to have someone around the house knitting, and there are a lot of cozy homey connotations that work for knitting as well.

I started talking about the ways in which craft and activism were related, and one day at a knitting circle, someone piped up with “You could call it craftivism!”

In late 2002 I came across a link online to a workshop by the Church of Craft that used the word. I Googled the term and there were four hits. I had this opportunity. I thought, I can putthis word online and track it. I was like, what if I don’t tell anybody about it? Really my whole thing is, I’m going to come up with this idea and whoever finds it, finds it.

I’m not one for promotion; it’s kind of something I’m fascinated by, why people find out about craft and activism and what it means for them.

My whole thing has been putting things out there and seeing what resonates – that’s the fascinating thing for me. I had talked about it on a class message board, now long defunct, which went out to people all over the world.

For a while you could track the word back to me. My friend in my knitting circle told another friend and there was always a direct link. Eventually I got an email from an artist in Africa who said she had found the idea and we didn’t have any common connections, so I knew the idea was spreading beyond just the people in my own craft community. But it’s nothing new, it’s been around for centuries, so it’s necessarily like I’m making something up. I just took what’s there and created an umbrella term for it for people find each other.

I was getting e-mails from people in places I’d never been that were way outside my demographic at the time, which gave me the idea that it was getting to be something larger.

Craft has been seen as a pastime – people denigrate it as somewhat worthless when in fact it can in fact be used as a strength – but the trick is that it’s used as a strength because it’s been seen as something that’s worthless. Using something that everyone thinks is weak and not important – and you’re using it to talk about justice so you have people saying wait – what?

A lot of times it represents an empowering presence to their craft and creativity that wasn’t there before — specifically related to craftwork, which has been demeaned for hundreds of years. When you’re talking about issues, you want people to think and wonder why you’re doing this, because it invites a conversation you may not otherwise have.

Putting craft messages together gives it strength.

Tracy: When did you start working with others to teach them craftivism?

Betsy: I lived in a house owned by a woman named Rachael Matthews, who at the time was running the Cast Off Knitting Club. She had a book out last year (The Mindfulness in Knitting: Meditations on Craft and Calm). She was doing public events in London, and I would go with her and others to help. I would go help people learn to knit on the tube and help them at festivals – so I was able to get a front row seat of how people were brought into public acts of craft, so I got to see how it affected people.

Tracy: And how did it affect people?

Betsy: Well, people had a curiosity about it. At the time it was the early 2000s, and things were a little different in England. Craft was something definitely more toward the forefront of peoples’ minds. Perhaps it’s because there are sheep everywhere, and wool – I started looking into this and started getting into crafts around 2001.

I saw how it was something really uncool in the US but verging on cool. And then I moved to London a few years later and the same thing was happening. People were getting more into it…. But when you look back in history, in the ’70s and ’80s, there was a reclamation of craft that came back in some respects.

Tracy: At that point it was just craft, without the connection to art. At what point was that connection made?

Betsy: So I started making it when I was in New York in 2001. I was sitting around knitting and I started thinking about activism, and what people thought of activism. At the time there had been WTO protests in 1999, and there had been a lot of destruction in that one. I was on the East Coast and I saw a lot of photos of people from the Black Bloc breaking glass, destroying things, and people were saying that was activism. And I said wait, that can’t be all that activism is. I thought about the way my grandmother when she was alive knitted hats for babies in the local hospital, and how in its own way, that was a form of activism, because all activism essentially is, is wanting to create a better world, and working to create it.

Some babies are born with less privilege, and instantly when they come out of the womb they need hats and toys while other babies don’t. So they (volunteer groups) knit hats for a lot of different hospitals so the babies have something. And I started to think about how that was activism. But there was a lot of pushback, and people said, “That’s not activist.” And I was like, why not?

Then I thought some people write checks to organizations and that’s their personal form of activism; and people volunteer for events. There are different ways in which you can use your voice and your skills.

I just thought about how I could use what I know to make the world a better place. And how other people are doing that, and how they’ve done that traditionally. For example, if you look at Gandhi. He started an initiative that had Indians spin their own cloth. He said we’re going to make our own cloth so we don’t have to rely on the British. Starting something like that was its own form of getting craft and activism together. And that was well before my time.

Another good example: There was a peace camp against nuclear war in England called Greenham Common outside of a nuclear facility. And they made all these quilts and different crafts projects about nuclear war and why it’s bad.

There are examples of prisoners of war who used craft in different ways – to remind them of their homeland, to express their resolute spirit against their captors. So there are different ways in which people have used craft as a form of resistance.

But that could be resistance to a greater force; there are also works that people have done related to mental health, to an illness; it can take all different forms. Ultimately the really important piece is that when you work like this, you’re better able to show up for yourself, for others, and for the world. Because I think so many of us are silenced because of things that have happened to us or to others. So working in a private space like craft helps us to really think about and define what we want to believe in and what we wat to say. It’s a private space to explore our feelings. And technology has given us a great way to share that with sharing photographs and images.

Before, you had the process of craft, which can be its own act of its own resistance, just in making something. For example there were Chilean women making tapestries about what the government was doing in the 1970s under the reign of General Pinochet where people were disappearing. It was happening in Argentina, people were disappearing as well. And so they made tapestries about the people who disappeared, some that said things like, “Where are they.” But they couldn’t legally do that and so it was a risk to make these pieces, but it was speaking up. So there are different ways where people have taken a process to help people work through their own feelings. They would work together in workshops at the local Catholic church. And in Argentina, the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo – they were women who originally used diapers onto which they embroidered the names of those who were missing, and wore them on their head, they showed up in the public square with what later showed up as headscarves. It’s been a private way that you can make public if you want. And now with something like Instagram you can make it as public as you want to, because you’re able to share it.

So the process is important, and the product is important, and now you have the photograph.

Tracy: So it’s enabled craftivism to take off in a much bigger way.

Betsy: Yes. It’s been interesting to watch – because it’s given people a way to talk about things that maybe they didn’t have an ease to talk about before, and share them online and have discussion.

What I didn’t realize when I started writing about craftivism, I didn’t think that anybody – you know, you come up with a term and you never think it’s going to be used hundreds of thousands of times. I guess people do now; people want to create viral content. But I was like, maybe I’ll find a few other people, and they’ll like what I do. But now that it’s been around for awhile, people can search for the term on Instagram and I think there’s like 28,000 photos now with that hashtag, and they can find other people who are doing kind of the same thing. So over time it’s become a community, which has been a great surprise and quite lovely, actually. I never in a million years would have thought that would happen, back in 2003.

Tracy: Right – back then the whole concept of “viral” didn’t really exist.

Betsy: Right! And I think everyone tries so hard to be viral now, and when people talk to me now about craftivism and ask me, How is this creating change? And I think that a lot of times we think so hard about numbers, or how many people are we affecting. And a lot of times with the internet and social media now we can say oh, we only have x number of followers, so we’re not affecting as much change as we could. And we forget that if we can make just one person think about how they vote, or think about how they act, or think about how they can use their creativity to make their voice heard – that is change.

But we forget that – just helping one other person is important. Because we all have had moments where someone has said something to us that changed us. I think a part of what I have been doing is trying to make sure people know they have permission to do work that feels important to them. Because a lot of times we don’t give ourselves permission to say things that may cause a difficult conversation to happen or may be something that isn’t pretty, necessarily – because we have lots of ideas about how craft needs to look this way – but it really doesn’t. Craft can look any way we want it to look.

We have a lot of cultural constructs – and there are people who are taking food back and saying we need eat more non-processed foods and we need to think about what we’re putting into our bodies, getting back to all-natural ingredients. Like last night I made a pumpkin vegan mac and cheese that was really good. So what this is doing basically is taking the cultural construct of what we think of as craft and thinking about it in a different way.

Tracy: What are some of the campaigns you’ve been most inspired by?

Betsy: I think the ones that continuously blow me away are the ones I find out about in history – like some the ones I mentioned in Chile and Argentina – to me the most inspiring things are the things that happened before social media. Because it’s relatively easy now to publish something and have it be seen by thousands of people. But you have other people who have been doing work that is forgotten and unheard, and stories that haven’t been shared. Those are the ones that are inspiring to me.

Tracy: And especially in the face of such repression – I mean they could have actually been put to death for those things.

Betsy: Right. And there are a lot of amazing things that are happening now. But the ones that excite me the most are the ones when someone comes to me and says, “Hey have you heard about this woman’s work,” in a country that no one is really talking to me about, which we are able to access because so many things are digital now. Like I found out recently through an artist on Instagram about Sojourner Truth and how she was knitting. You will find she mentions a book (Nell Painter’s Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol). Which I was able to download and read about that – which to me was super exciting. Because gosh I’ve been doing this so long and I’ve never heard anything about how she’d used knitting, which was amazingly inspiring.

Tracy: Yes, that is inspiring! And I suppose it’s the fact that you’ve put a name on it that allows people to start putting these ideas together, right?

Betsy: Right. Because people can look for a hashtag and find that a) they’re not alone, and b) other people are doing this and they can follow them, and they say that – what? People have been doing this for hundreds of years! So it’s definitely nothing new, but it’s been a joy to be able to watch people find inspiration in their own craft. Because it was hard for me to be able to put a definition on it for a really long time, because the most important thing was saying to people, ‘You can use your craft in activist ways,’ and that means however you see fit. And that’s going to mean a different thing to me and to you and to different people around the world because of your own history and your own skills.

Tracy: OK so now let’s fast-forward to 2018, and all the things we’re facing right now. What is it about craftivism that might be especially important in these times?

Betsy: I know in America, a lot of people are scared and a lot of people haven’t been heard. And I think you can use your craft as a way to share your voice, and I think sometimes with some populations it’s not safe unfortunately with where we are politically to talk about your feelings or to put your name to it. So by making pieces that express your feelings and your thoughts, it’s a good way to explore how you’re feeling and then to share that piece with your friends – and you may not want to share it on Instagram but you can share it with people you know. And that to me is important.

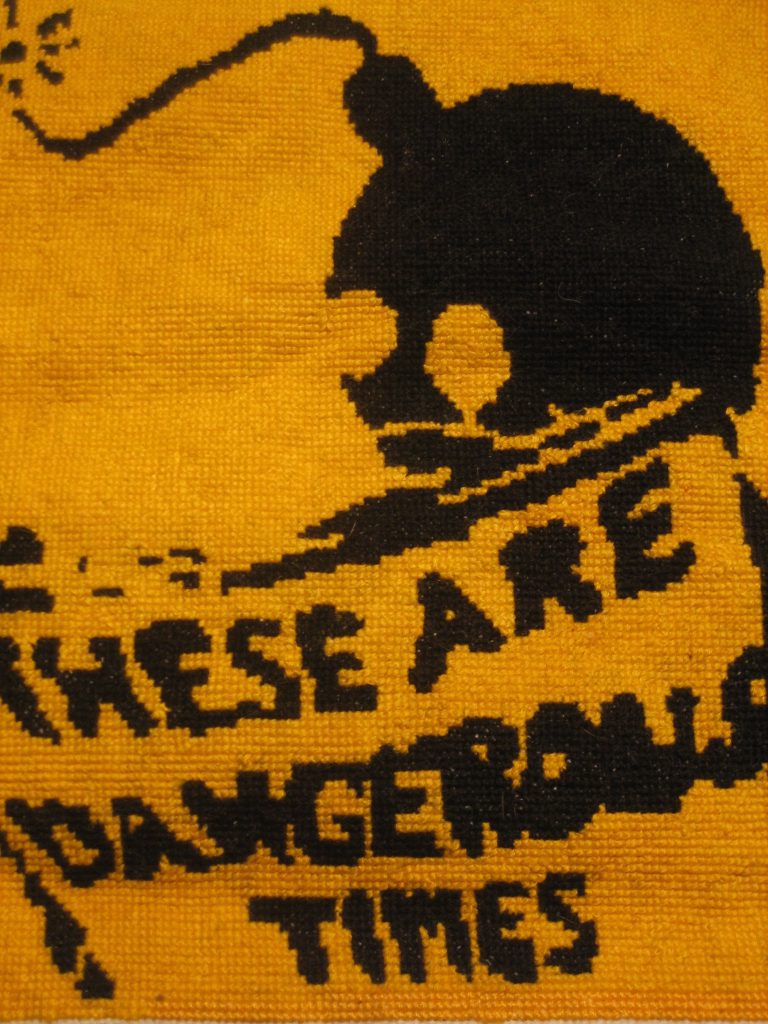

I did some pieces on anti-war graffiti from around the world, and cross-stitched them as a way to process my own feelings about war, when we were at war – I mean we are still at war in Afghanistan. But in the mid 2000s I wanted to explore because I knew people who were over there; I have a family with a military history, and I wanted to explore my own feelings. And so working on these pieces, which took many, many hours, was a great way for me to explore my own feelings about war and how it affected me and how little I felt I could do anything about it. And so I made a series of pieces based on graffiti from around the world to show that people all around the world are against war but very few people actually make the decision to go to war.

So I think craft is a great way to explore your feelings, and it’s a great way to talk about your specific feelings because if you are making something you can – it enables people to have very deep conversations. Because I’m talking to you on the phone right now, so if I stop talking for two minutes you might wonder what’s going on. But if I was in front of you and I was knitting or crocheting or quilting, then that would be a natural pause. So it allows you more space to talk about things that are difficult.

Tracy: And that might be really important in our current political environment.

Betsy: Right. Because I think people are scared about what’s happening and it’s hard to talk about things with other people, especially if you have a family or a partner or a community that’s against what you feel. You can feel alone.

Tracy: What kinds of misconceptions have you encountered about craftivism? You talked about craft as being an undervalued thing.

Betsy: Craft has been thought of as something that only women of a certain age do. When I first started knitting I was in my mid-twenties. And people were like, “You knit?” and they were confounded by it, often. And then they were like – wait you know other people your age who knit? That’s really weird! Now I’m almost in my mid 40s so it’s a much different place. People think about craft a lot differently.

But people have a misconception about what it means to craft and who crafts. I think if you look at the social media feeds of a lot of craft companies you’re going to see a lot of white women – and that’s a misconception, because people of all backgrounds knit and sew and embroider and quilt, and there’s a long history of that, around the world, from every country. So there are misconceptions all over the place about who does these activities, and I think it does a disservice to a lot of the population because it doesn’t show them that this is for them. So if you’re honest and you use certain hashtags you can see – and it’s like “Oh my gosh there are a lot of people in my own community who do this.”

It’s being discussed a lot more but hasn’t been widely thought about.

Tracy: If you had an unlimited budget and could take on the biggest project that you always dreamed of doing, what would that be?

I have a project called “You are so very beautiful.” And it’s based on the fact that we all hear and see thousands of negative images every day and sometimes we hear them from our own minds, we tell ourselves we’re not worthy or not beautiful, or we see that in advertising.

If I could I would do a project with these affirmations and had the money to make them and invite people to make them all over the world in their own languages.

The project has been recreated in different countries which is fantastic – I got several emails from people in Mexico, saying – I want to do this in Spanish; is that ok?

It’s been recreated in English speaking countries like Australia, Canada, England. The whole point is that once you think you are worthy, once you think you are enough, once you think you have something to contribute, you are going to go on to more fully use your voice than before, and be a better activist, be a better person, be a better citizen. And so I think that stepping back and helping people to become better people – or to believe in themselves more — is kind of my main focus right now.

I think there are lots of men and lots of people who are non-binary and people across the board from different backgrounds who think they’re not worthy, and I think it’s important to remind people of that, too, and this is a message everyone needs to hear, although it is primarily focused on women. And people may say, well, that’s not activism well to me it is, because you’re allowing someone to realize that their voice is important. And someone who realizes their voice is important is going to go on to do better and stronger work than someone who think they’re not worthy.

I want to hear their voice – A lot of times they may not have been told they can speak up, or they may feel it’s unsafe. I feel that’s really sad, and there have been periods in my life when I have thought that.

And I’ve found that taking one of those negative thoughts that we think and turning it positive – it’s a very granular approach to activism, but that’s where I am. Because I can tell where what one person has said or what one person has done, has changed how I think or view my life or myself.

Tracy: Can you give me a visual image of what these projects look like?

They’re tiny signs, like palm sized – hashtag – #YASVB, for You Are So Very Beautiful – you can see some examples. They are stitched with an affirmation, like “You are worthy.”

It could be: “You are brave, you are strong, you are not alone, you are magical,” and then putting that on a small stitched sign. And then I started leaving them out in public for people to find. I started that about three years ago.

People have found them and people have had a really good response. You put something out there in the world – and then people post them on Instagram and say I found this message from the universe and it’s just what I needed.

And sometimes people will say, “I found this and it meant a lot to me and now I’m going to put it back out for someone else to find.” And I never would have guessed that would happen, that people would find them and then want to pass the message on.

Sometimes I put a piece out without the hashtag because I wanted to see how it felt differently, because I wondered, “Are you doing this because you want the reward of someone contacting you? or are you doing it because you want to make a difference?”

Tracy: You’ve been doing craftivism now for about 16 years. During that time, what are some stories that really stay with you, that you will always treasure.

Betsy: When I think back through all of it, it’s just thinking about how I had a sense of empowerment in my own craft when I got started, and thinking about how I thought maybe it was just me – you think you’re alone then you put it out in the world – and then you realize you’re not alone – that part is really important, and watching people develop their own sense of empowerment is amazing. I never thought that would happen, so it’s been a real delicious surprise, to watch people see their own work, and their own skills, and their own voice as important, especially when they didn’t start out seeing it that way.

There have been hundreds of people saying the same thing. Which to me has been really beautiful. When you get that reconfirmed it becomes like, This is great to help people find their own voice, because this whole process has been about helping me to find my own voice.

Tracy: Are there any questions I haven’t asked, or anything else you’d like to add?

Betsy: That last point is something I’d really like to share. Because it’s something that anybody with a few simple supplies can do – and this can be separated out in so many ways, it doesn’t have to be craft, necessarily. You could find your own voice in baking; you could find your own voice in tennis; you could find your own voice in running — it’s about exploring what your interests are and finding your own voice within it.

You can explore her projects at craftivism.com, hellobetsygreer.com– and of course on Instagram.

- A Year of Listening, Resistance, and Hope: Reflections from The Esperanza Project - December 30, 2025

- Arts to Breathe: A Continental Act of Dignity - November 28, 2025

- “It’s not grass, it’s a milpa”: Defending Life on Avenida Federalismo - October 8, 2025

activism artivism Betsy Greer craftivism Elizabeth Vega Sarah Corbett