By Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez

with production by José Huamán

photos from the Esperanza Project film “Legacy of the Andes”

High up in the Andean mists near the sacred mountain of Wamanlipa, a long day’s journey from Cusco, lie the windswept communities of the emblematic Q’ero people, believed to be the last living descendants of the Inka. Hatun Q’ero, the most remote of the five Q’ero communities, wasn’t reachable by road until 2017.

The ruggedness of the landscape and the altitude, up to more than 4,400 meters (14,000 feet) above sea level, was enough to insulate the people from the Spanish conquest and then from Peruvian interference, and has allowed them to keep their profoundly spiritual culture intact. It also helped to keep Covid at bay – for a while. But it has been the peoples’ own defenses, their medicinal plants, and their reciprocal relationship with the forces of Nature and each other that has helped them to recover with no major casualties.

This story is a part of Legacy of the Andes, the long-awaited second part of the Cosmology & Polycrisis transmedia series, produced by The Esperanza Project with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The One Foundation. Watch the accompanying film, read related stories, download the book and explore the entire transmedia series here.

The news arrived in the community of Hatun Q’ero via radio, as Fortunato Flores Chura, former president of the village of Challma Chimpana, tells it. At first, people were afraid. “Gossip of all kinds appeared,” recalls Fortunato. “Newscasters commented that everyone over 65 would die, and that the children would die, too. And readers of the Bible said we were at the end of the world.”

People would go out to tend their fields and run into each other and share the news, and the gossip spread like a grassfire. “We were honestly all very frightened at first. But the months went by and the fear has been lost now. Instead, we have our medicines in our plants. We will live preventing (the illness), and with this we will heal ourselves.”

Community members in the cities made an exodus back to their villages, and many brought eucalyptus back with them, which was used in infusions and vapors as a decongestant. Some brought matico, used widely throughout the lowlands as an immune booster and also to treat covid symptoms. “These plants are effective, and they grow too in the lower parts of our community,” he said.

Para leer esta historia en Español, vea Los Q’ero: El Último Ayllu de los Inka

Fortunato and others, like Andean priest Pablino Chura, consulted “Mama Coca” — a millenary divination technique using coca leaves – and received the message that if Covid arrived in their community, the effects would be light.

“When I see in the oracles asking the Pachamama, the Apus, the Father Sun, the Mother Moon invoking their protection, to those of us who believe in her, if you hold on to them with faith – as in my case, they take care of me, they protect me, and they also take care of other people,” says Fortunato.

That message turned out to be true – many people were infected by the virus in the Q’ero communities, but as of May 2023, multiple sources, including Rolando Sonqo, current president of Hatun Q’ero, and Penelope Eicher of the Heart Walk Foundation, which organized a medical team to attend the Q´ero communities of Kiku and Hapu, had heard of no deaths.

Martín Q’espi Machacca, one of the last living Altomisayoqs — the highest priest of the Q’ero Nation — was on the front line of the response in his community of Aynas. “We just defended ourselves with haywarikuy (offerings to the Pachamama), the despacho ceremonies. We put our offerings for the illness in the way, so that it passed by without affecting our communities.”

Another factor was key, according to Don Martín, as he is respectfully known by his friends and many followers: their diet, and their way of life.

“To face the Coronavirus, we relied on our own organic food, on our own crops — such as chuño (dehydrated potato), on our medicinal plants, on the strength of the Apus, the Pachamama, on everything that Mother Nature gives us.

“That’s why in many other places there have been many consequences, because their diet is not good… The Pachamama and the Apus are the only ones who can solve these difficulties through our offerings and petitions so that all sorrows subside, and all this imbalance that we have on our planet will come to an end.”

Now, however, the Q’ero face another potential threat: that of the mining companies that seek to extract the gold that lies beneath their lands, and are threatening to create divisions in this unique and emblematic nation, declared a Patrimony of Humanity by the Peruvian nation.

Cusco filmmaker and Cosmology & Polycrisis producer José Huamán traveled to reach two of the most remote villages of Hatun Q’ero, Challma Chimpana and Qocha Moqo, in January of 2021, accompanying the villagers as he had many times before over the years as a filmmaker and a friend.

At home with Juan and Juana

Juan Apaza Sonqo, president of the village’s Association of Parents of Families, sat on the earthen floor and knitted a cloth of fine-spun alpaca wool as his wife, Juana Flores, prepared a tea from a mixture of herbs over the fire in the middle of the floor. Unlike Fortunato, Juan was concerned. The government has not communicated with them, he said, nearly a year into the pandemic.

“We don’t know what the government is doing; it is said that they are already bringing the vaccines, that’s just what we heard. We don’t know what this disease is like. Here we have small diseases like diarrhea, the flu, is it maybe like that? What form will that pandemic take? We don’t know … we worry that suddenly it could come in other forms, and it is possible that it will kill us.”

Like many of her neighbors, a year into the pandemic his wife, Juana, was a skeptic of the government’s version. She has no use for face masks in the highlands, socially distanced by nature from everyone but a handful of neighbors.

“We found out (about the pandemic) from our neighbors who came from outside,” she said. She spoke of the community members who had returned from the city, most of whom had undergone a 10-day quarantine in the nearest town, Paucartambo, before returning, or else they were turned away and required to go back and quarantine.

“So we looked for medicines like the pupusa, the huamanripa, sasawi… we thought about the weqontoy, the sallika, the alcohol. That’s all we use. We ripen them in each ravine; that’s the only thing we cure ourselves with.”

Time-honored local plant medicines in Hatun Q’ero include sasawi (leucheria daucifolia) and huamanripa (Senecio calvus, used for coughs and congestion), and pupusa (Werneria poposa) used to calm fevers.

Some of the plants they use grow nearby, in their village. Others grow further up the slopes that surround them; others grow in the lower regions. The inhabitants of Hatun Q’ero live in six villages at altitudes from 7,000 up to 14,000 feet, and they take full advantage of the range of altitudes.

“This is boiled and we drink it hot,” she said. “Then we will deposit it in a gallon or in bottles, we will macerate it with alcohol, and that is what we will drink. Here in this village, nothing has caught us yet—it hasn’t killed any of us yet.”

Like her neighbors, she knows that staying healthy goes beyond plant medicine, and is highly conscious of the spiritual nature of wellbeing.

“We also invoked our Apus at the time, all the time. We also walk together with our animals. I don’t see the coronavirus coming here.”

Reading the Coca Leaves

Coca is a sacred plant in the Andes, and even though neither Juana nor Fortunato mentioned it among the medicinal plants that they use, they frequently popped a few leaves in their mouths as they spoke. Coca has been cultivated in South America for about 8,000 years and was as valuable to the Incas as gold, in part for its ability to impart stamina and energy, and in part for its use as a divination tool.

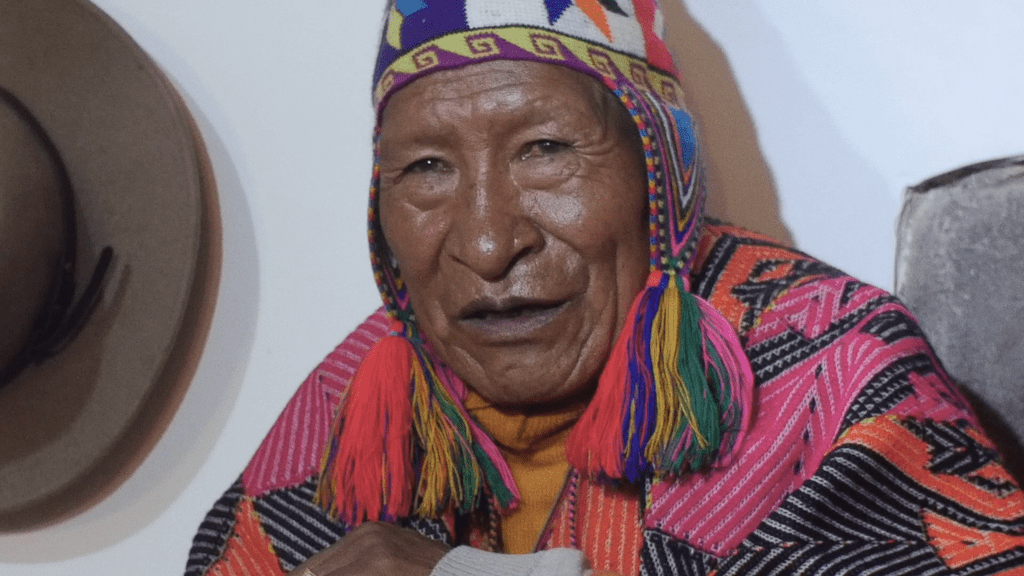

Andean priest Pablino Chura is one of those who regularly uses coca leaves to peer into the future. C&P producer José Huamán paid him a visit in his round stone hut high in the mountains, shrouded in clouds, during his January 2021 trip. The idea was to interview him on his views about the pandemic. He had never heard of it, and he showered José with questions: What kind of disease was it, where did it come from, what caused it, what was the medicine for it?

Huamán’s answers, like those of humanity itself, were inconclusive.

“We can also look at the coca leaves to find out what it is like,” said Pablino helpfully. He squatted on the dirt floor of his home and spread out a striped cloth, scattering a bag full of coca leaves on the cloth.

He examined the leaves closely in silence. Then he began to point at a particular configuration.

“Let’s see, it’s going to come to this town… it’s going to come, but lightly. Look, that’s what it’s saying… it will come lightly, a little bit. It will not be intense, strong, crazy.”

He paused, chewing a mouthful of coca leaves and peering down into other times and places.

“In large towns, let’s see… It is happening, yes,” he said, pointing. “Here it is, here, right now there are many sick people in the large towns. Here in Q’ero there is no disease yet. It is far away here, it has not yet arrived.”

Now he began to stack the leaves into a small, neat pile.

Territorial Troubles for the Q’ero

“We will give good remedies, we will cure them. The health posts are useless, they don’t know anything! Here, we are ready.”

Matias Quispe, 65, is one of many Q’ero who believe that the pandemic is a result of humankind’s disconnection with the Earth. He reaches into the handwoven chuspa on his lap and pulls out a small handful of coca leaves, which he blows on reverently, calling out the sacred names: “Apu Wamanlipa. Apu Wayruroni. Apu Ausangate. We invoke your protection and your guardianship.”

The clouds gather around the peaks at his back under a slate-gray sky, and he gazes into the distance as he speaks of a world that has forgotten its mother.

“We think that (people) do not remember the Pachamama, the Apus, for this disease to appear,” he said.

People should not deforest; for that reason there are all kinds of diseases. Many wild animals live in the forests. Fires decimate them. They die cursing us, wounded, burned. The disease is reproduced from this…

Matias Quispe

Q’ero elder and farmer

“They are burning the hills, these human beings who do not believe… People should not deforest; for that reason there are all kinds of diseases. Many wild animals live in the forests. Fires decimate them. They die cursing us, wounded, burned. The disease is reproduced from this, for the other species of animals and also for humans.”

Quispe was speaking of the fires in the Amazon; the environmental apocalypse he described has not entered Q’ero territory. But trouble looms below the surface, because the mining laws in Peru, as in many countries, give the landowners surface rights, but the government can and does control the subsoil and all the mineral rights that go with it.

This is a source of concern for former president of the Q’ero Nation, Fredy Flores Machaca, interviewed by telephone in March of 2023.

“When the miners start, they remove all the minerals from the communities and leave it totally abandoned, totally disordered, a disaster,” said Flores. “So that is very worrying.”

And there is reason for concern. In 2018, when Flores was president, some 16 concessions and titles had been granted to the mining companies; today that number has grown, according to an analysis by the Peruvian NGO CooperAccion, which shows that there are now 26 concessions and titles comprising around 61% of Hatun Q’ero, or 15,800 hectares, of the Hatun Q’ero territory, that have either been granted or are under consideration (see map).

Seeing the damage that was done in neighboring communities that allowed mining companies to enter, the communities of Hatun Q’ero came together, said Flores.

Nowadays, he said, they understand their right to free, informed and prior consent for activities that affect their territories under the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which wasn’t always the case.

Don Martín Q’espi, interviewed in April 2023 at the Hatun Q’eros Cultural Center in Cusco, says that human beings have confused the meaning of the gold referred to in the Inka prophecies, just as they did in the days of the Inka empire.

“Many believe that the gold referred to in the Inka prophecies is physical, ” he said. “No, it’s not like that. It is the knowledge that we keep in these places; the gold and silver are Mother Earth,” explained Q’espi.

“Nowadays there are enough lies, there is enough deceit. And people now think more than anything in economic interests. How is it that, for example, they want to damage Apu Ausangate? There are already others who are being annihilated by mining! People are growing quite greedy now, they don’t even respect Apus anymore! Before, there was a lot of respect. Now it’s all about the money. That is why we do not want mining to reach our Ausangate or our territory, because this would change and unbalance our society.”

He assures that despite the mining concessions awarded by the Peruvian government to more than a dozen companies, the forces of Nature will impede the miners from doing their job.

Many believe that the gold referred to in the Inka prophecies is physical… It’s not like that. It is the knowledge that we keep in these places; the gold and silver are Mother Earth.

Don Martin Q’espi

Altomisayoq

Current Hatún Q’ero president Rolando Sonqo Apaza is also concerned about the threat of mining in the territories, he said in a telephone interview in May 2023. Many Hatun Q’ero members, tired of living in extreme poverty, are not opposed to mining, he said.

Although some people in the communities see mining as a valid way of life, the political administration of the ayllus is still deeply linked to the spirituality. Leaders like Sonqo still live strictly following the teachings of the ancestors, understanding that damaging the mountains means to attack their Mother, and the real rulers of their territory, the Apus. “While we lead our people, we´ll never accept mining in our land… The Pachamama knows that is not a good thing to do.”

Anthropologist Regis Andrade, who has served for 12 years in the Q’ero territories for the Ministry of Culture, said his department has tried to support the Q’ero in their territorial defense but that ultimately the Ministry of Energy and Mines is the agency with the authority to grant mining concessions. Although the agency is obligated to consult with Indigenous peoples before engaging in mining activity on their lands, much of the Q’ero territory has been parceled and designated for mining without that consultation happening, as has been the case for Indigenous communities throughout the Americas.

Andrade is part of a working committee that has been formed by the municipal government of Paucartambo and the Ministry of Culture together with Q’ero leaders to address issues and problems of the Q’ero communities. As of yet, the issue of mining has not come up in the group’s meetings, he said.

People believe that they can go and bang around and bring back gold, but no, the force of Nature is there, like the wind, the lagoons, the rivers, where you might even have to pay with your life.

Don Martín Q’espi

Altomisayoq

The Q’ero nation has been subdivided for mining,” said Andrade. “The Minister of Mines has already parceled out the parts for the mining companies … But the peasant communes and the specific issue of the Q’ero nation have not really been consulted. The mining companies dialog directly with the State. But in that aspect I think that the State, Energy and Mines in this case, are not fulfilling their corresponding role.”

He has personally contacted the Ministry of Energy and Mines to ask for specific information regarding the amount of land in the territories that has been concessioned, but they have not responded to him, despite multiple calls; the person in charge is always unavailable, he said.

He has observed in his visits to the communities and talks with community members that some are in favor of mining, and some are against it. “There is a double discourse,” he said. In general, most are reluctant to talk about it.

“No mining exploitation is being carried out in the community of Hatun Q’ero, but there is a risk that in the future if they carry out exploration … that they will exploit the minerals that they find”, continues Andrade. He worries about the potential for conflict that the mining companies’ presence in the territories is fostering.

“I feel that mining is dividing communities at the level of community organization. There are always divisions; some want mining, there are others who don’t want it… who say, ‘But they are going to contaminate the lagoons, they are going to contaminate the streams, the water itself.’ In the future, a conflict could be generated by this division that exists within the communities.”

But Altomisayoq Don Martín says not to worry. “People believe that they can go and bang around and bring back gold, but no, the force of Nature is there, like the wind, the lagoons, the rivers, where you might even have to pay with your life. You can’t get to these places. The strength of Pachacutec, of peace, the strength of the Ñustas is always with us.”

Living the Sweet Life

To Fortunato, what’s at stake is Sumaq Kawsay in Quechua, Buen Vivir in Spanish, or good living, in the Andean way. Abundance, plenitude, the Good Life, means being able to share with your neighbors. And it means being in tune with the land of which you are a part.

“That’s how it is in my town, in my community. Back then our ancestors, our grandparents lived in harmony, their farms worked in reciprocity — Ayni. If someone lacked some resource, they shared it. That is the sumak kawsay, to live with sweetness, that is, within the family home. Those who live well value it, respect it and consider it an example for all.”

Fortunato gives the example of the minka, or minga – a collective work group that moves from field to field, planting, harvesting, weeding.

“If your neighbor has plenty of animals and you do not, he can give you a horse. It even applies to money; if you have it, you lend it to those who do not have it. If you have plenty of help, share with those who do not. That is my practice, for me, the sumak kawsay.”

Ayni must be practiced with the land as well as with the human community. This is done by making offerings: of the sacred k’intu or trio of Mama Coca leaves, prayer bundles, or other ceremonial items in a ritual known as a despacho, where offerings and prayers are made to the Pachamama to restore the balance.

But one of the most important offerings to the Pachamama is our own buen vivir, explained Fortunato – our own commitment and practice of living well and in harmony.

“Living with the Pachamama, with the Apus, with our winds and our snows… to overcome the illnesses as our grandparents taught us to be in touch with our caretaking divinities, making permanent reciprocity, so they are our defenders against all the evils; with them we make allin kawsay, buen vivir.”

The Pachamama wants us to live well, he emphasizes.

Fortunato laments the urban tendency to use pharmaceutical medication for everything, even with children, which he believes weakens the body’s defenses. “These days it’s a pill for everything, but as I see it they are only painkillers, they only calm the symptoms, I don’t believe that they really heal or cure. Now if I get the flu, I’ll be fine by tomorrow. I don’t use pills; to this day I have never bought them anywhere.”

We work in the chacras with the animals, with everyone joyful, together like brothers, contented, happy, laughing… if you work alone, you work without speaking, it’s a shame.

Matias Quispe

Q’ero elder and farmer

Matias shares Fortunato’s skepticism regarding pharmaceuticals. “Here we do not have the habit of curing ourselves with pills or injections, only with our medicines,” he said. “We defend ourselves with our medicinal plants and consuming the foods that we produce, not the ones they sell in the stores – potato, chuño, moraya, corn, fava beans. With the winds and the snows we also cure ourselves.”

He also cites the importance of ayni, in reciprocity with the Pachamama and in the context of mutual work. “We work in the chacras with the animals, with everyone joyful, together like brothers, contented, happy, laughing… if you work alone, you work without speaking, it’s a shame,” he said.

“The animals are not happy either when we don’t work in ayni; on the contrary, when you practice ayni, it’s pure laughter. You work this way again and again, it’s generous reciprocity. These practices are in danger of being lost, little by little.”

According to Qocha Moqo community member Dionisio Machaca Apaza, interviewed in March of 2023, no one in his village had been infected as of that time.

“Covid did not reach this distant village, nothing at all,” said Dionisio. “This disease does not exist in our village and it is because we feed ourselves naturally. Our foods do not contain chemicals; we always produce our food naturally, and there are also all kinds of remedies for these types of diseases. There is a selection of herbs, all products are obtained from nature. We do not use any chemical products or things; that is why we do not know this disease. We are strong, tough human beings.”

Don Martín, who was struck by lightning three times as an initiation and a sign of his calling, is one of a tiny handful of living altomisayoqs, or Andean priests of the highest level, and as such, he is able to communicate with beings of other dimensions. “At this time we talk about this path that is always circular,” explains Q’espi. “This wisdom, this knowledge that we say will always come back to us… I have the great honor of having known this path and this wisdom.

“And this wisdom will return, we are sure of it.”

Q’espi invokes the spirit of all who work with the energy of Pachamama, “the true energy,” as he calls it. “It is the union between all of us, the union between all those who believe in the strength of Pachamama, to create enough changes. It is not only in the hands of the Altomisayoq or the Pampamisayoq. It is in the hands of all of us to achieve this change that must exist on our planet.

“That is why we must carry this knowledge in our heads, in our feelings, in our hearts, in our works. You have to ask with the truth, you have to ask with all sincerity, reactivate the main altars that we have in our tradition – only then can we help our world. This is how we have to work to be able to change our planet, and I will never tell you that it will not be possible.

“Yes, everything is possible!”

Many thanks to Elizabeth Jenkins and Fredy Conde Huallpa of the Wiraqocha Foundation for their assistance, especially with the Don Martín Q’espi interview for this story and the accompanying film, Legacy of the Andes.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

Previous page Next page