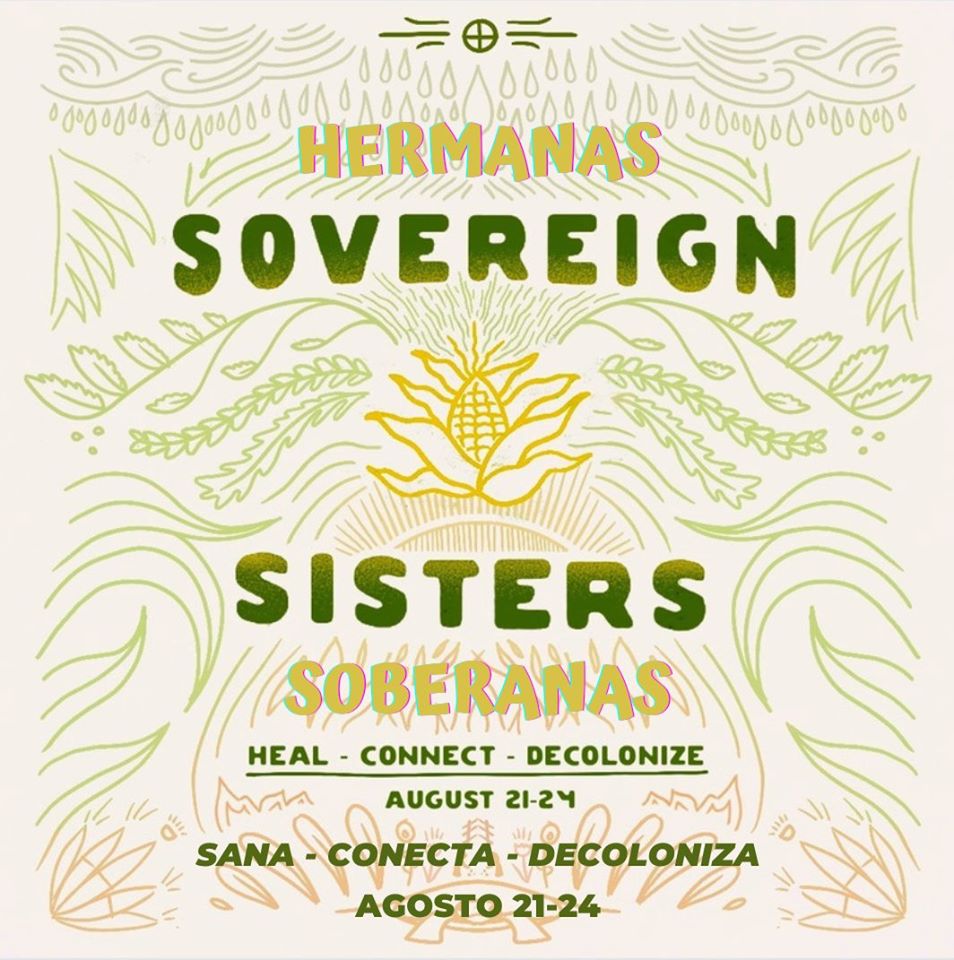

Sovereignty means different things to different people, but perhaps its essence is best displayed in times of challenge. And so it was for the powerful four-day Sovereign Sisters gathering held on the third weekend in August. Despite two of the group’s founders, Cheryl Angel and LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, being sidelined by illness and injury, the organizing committee forged ahead – principally Lyla June Johnston – and brought about a virtual feast for the soul.

Sovereign Sisters, the brainchild of Sicangu Lakota Water Protector Cheryl Angel, began as a gathering in the sacred Black Hills to thank the women who had supported her during the Standing Rock movement to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, and to explore the concept of sovereignty from the perspective of indigenous women. This year’s gathering was to have taken place in Standing Rock, hosted by the cofounder and icon of the movement herself, LaDonna. Excitement grew among the small “inner circle” of previous gathering attendees, who would be allowed to come and camp on the grounds of LaDonna’s Sacred Stone ecovillage in Fort Yates, on the Standing Rock reservation. From there, as the plan went, the main speakers would broadcast their message to the world.

But challenge after challenge emerged as planners grappled with the realities of the pandemic, and when Cheryl herself fell ill, it became clear that the gathering would be a virtual one. She was unable to summon the strength to appear during the meeting, but she took solace in knowing that something beautiful was happening as she fought for her life.

Artists and healers, scholars and visionaries, mothers and grandmothers and aunties were sharing their perspectives on the meaning of sovereignty in these times, and shared space for healing, collaboration and re-imagining of the world as it can be. Each day’s session began with an opening prayer and then a panel of four women discussing sovereignty, each from her own perspective. The innovative format included breakout sessions among random attendees to encourage new friendships and cross-pollination. It was self-organized, so that anyone among the 1,300-plus registrants could create their own thematic breakout room on Zoom.

The main panel each day was translated into to Spanish, and Latin American women were among the panelists, also forming their own breakout sessions; an estimated 200 registrants and presenters, from Argentina’s Patagonia to Ecuador to Mexico, joined in a powerful series of sessions that went on for many hours as sisters North and South shared from the heart.

A wide panorama of panels carried intriguing titles from ones like “Bridging the race divide: Mixed race/mulata/nepantla/liminal medicine for a world desperate for racial healing” and “White Women Ending White Supremacy Circle” to “Allies & Accomplices—Living the Language,” “Our Medicine is Resistance: BIWOC Healing Circle.” Other themes included Agroforestry, Land Back, Incarcerated Loved Ones, Food Sovereignty and Water Protection/Monitoring, to name just a few.

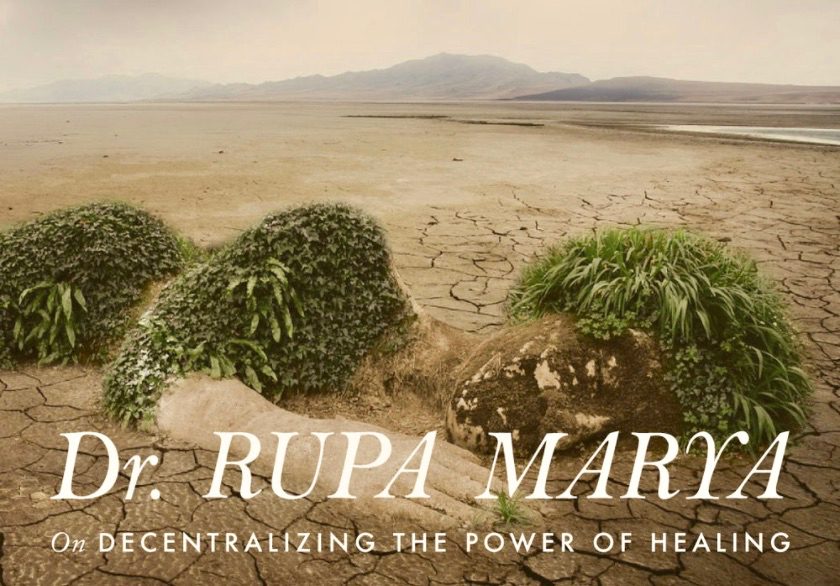

For a small taste of the Sovereign Sisters’ first online gathering, we share an edited transcript of the first panel, featuring physician and medical equity activist Rupa Mayra; Syrian-American rapper and activist Mona Haydar; disability rights activist Rebecca Cokley; and Quechua artist and activist Sarawi Andrango. We are currently seeking volunteers to help with the transcriptions of the other panels; if you are interested, let us know.

Lyla June: Welcome, everyone. We’re so grateful that you’re here. We have a really exciting day planned, and we’re very honored that you would all join us. A lot of organizers came together to make this happen from many different nations, people who are really trying to create solutions on the ground. I think it’s pretty clear that these colonial governments are not going to take care of us, so we’re excited to learn how to take care of ourselves and each other in the old way.

One thing I just wanted to say before we start is we love you very much. We’re glad that you’re here. We come from a lot of different backgrounds and walks of life. We’re probably not all going to agree on everything, and we would like to create a space where different viewpoints can coexist.

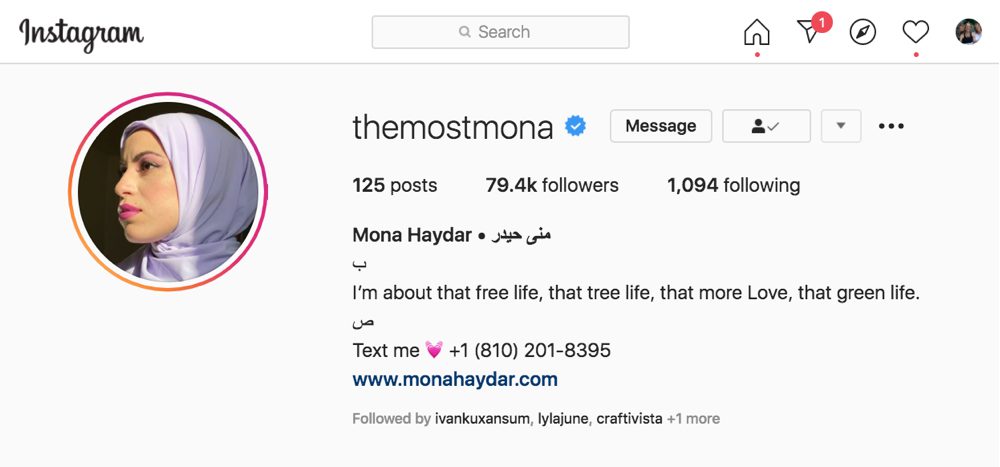

Mona is Syrian American; she’s a rapper, she’s really quite connected to the Earth, and she’s a theologian.

She graduated from Union Theological Seminary and also is Muslim. And we’re just really grateful that you’re here. I’ll let her introduce herself more. We have Rupa Marya, who is an M.D. She’s a doctor out of the Bay Area and coming from Pakistan, her family roots, I believe. But I’ll let her introduce herself more. And she’s really fascinated with decolonizing medicine and also happens to be a badass musician. So that’s good. We have Rebecca Cokley, who is the director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress. And we have Sarawi Andrango, who is from Ecuador. She’s a Spanish speaker and she is an artist and she really explores resistance through art.

Rupa. Would you be open to just sharing who you are, where you’re from and what you’re passionate about?

Rupa Marya: My name is Rupa. I guess you could say I’m Pakistani because Pakistan and India are creations of the British Empire, and my homelands were cut through with a border like a scar on the land. My family is from Punjab, and I was born and raised in occupied Ohlone Territory. My ancestors were from Punjab for the last seven or eight hundred years. Before that, we were warriors in the deserts of Rajasthan. I come from a deep history as a Hindu and Sikh woman, understanding the legacies of violence, of colonialism from many different places, but most recently the British, and as well as caste violence in our own communities. And understanding how that recreates itself in these other iterations that we’re seeing now globally. What am I passionate about? I’m passionate about healing and composting our grief into the beauty of healing and moving forward. I’m passionate about life and medicine.

Lyla June: Thank you, sister. We really appreciate your being here. If you would be open to sharing — and the reason I asked this: Who are you? Where are you from? What are you passionate about? Is because when I was talking to LaDonna, she said that’s the first sovereignty, is knowing who you are, which I know, in this world, colonization has not made that an easy question to answer. I just wanted to share that side note of why LaDonna wanted to start with this.

So Mona, who are you? Where are you from, and what are you passionate about?

Mona Haydar: Hello, everyone. My name is Mona Haydar. I come from Damascus, Syria. That is where my bones and my flesh were made. And in my tradition, we believe that you are made out of the earth that you will pass through. So just because we are born in a place doesn’t mean we are of that place, actually. And for some of us, that is true. And for some of us, we are naturally nomadic and diasporic and we travel. And I feel like a nomad, a traveler. I grew up in Flint, Michigan. I was born in Saudi Arabia. I have lived in the redwood forest in California. And I met my husband and partner, had my first child at the Lama Foundation in northern New Mexico.

And now I live in Santa Fe, New Mexico. So I identify as a person of the diaspora, and my lineage is both Damascene and Kurdish. And I have more roots than that. I mean, obviously, we can talk about blood and purity and all that stuff, but let’s keep it simple for now. And I just feel so, so blessed to be here. Thank you, Lyla, and prayers to our sister and her healing journey. Excited to get into this with you all. Thank you.

Lyla June: Thank you so much. Rebecca, would you be open to just introducing yourself a little bit: who you are, where you’re from, what you’re passionate about.

Rebecca Cokley: Thank you, Lyla June. Hi. My name is Rebecca Cokley. I was born and raised in the Bay Area and moved to Washington, D.C., where the land that we sit on now used to be Anacostan land. I live here in D.C. with my partner and our three children, who I am hoping to find ways to keep them entertained for the next hour, or they may show up as a special guest star.

I’m passionate about engaging across movements to work to ensure the inclusion of disabled peoples — of my people, with a broad definition for how we talk about what disability is as a culture, within all of our spaces and how it exists across communities; where 80 percent of people with disabilities in this country grow up with nobody like them in their families.

Being a Little Person, I have dwarfism. For me, it’s a cultural thing. Both my parents were Little People. Two of my three children are Little People. And so where some look at disability and see it as a diagnosis, we see it as a thing of pride and a cultural affiliation. And so that is what excites me because there is no movement alive on this planet today that doesn’t include disabled people. We just don’t include them well. And my goal is to help movements to get better.

Lyla June: Thank you, sis. We’re really honored to have you today. Now we’re going to hear from my sister Sarawi from Ecuador, an incredible sister. So Sarawi, who are you, where are you from and what are you passionate about?

Sarawi Andrango: I am Sarawi Andrango, I come from Ecuador, Abya Yala (Latin America). I work for the blooming and the flowering of people. My service is through writing, through my words, through poetry. I work as a community organizer, a cultural organizer.

I like to transmit what my grandmother, what my grandfather believed, what their philosophy taught, and to express that philosophy through art. That’s what my work is, what my service is. I’m very thankful and honored to be part of this sisterhood, this weaving of sisterhood that we are doing right now, to weave our sovereignty.

Lyla June: Thank you very much. Now I would like to ask Rupa, how does sovereignty fit into your work? What would you share with this group about sovereignty at this time? I know that’s a very broad question, and I want it to be broad so that you can really say whatever the heck you want to say.

Rupa Marya: Such a deep question. I am sitting here in Ohlone Territory in Oakland, California, surrounded literally north, east and south by wildfires, by fires that were started with lightning. I just got done with serving in the hospital at UCSF, where I work as a professor of medicine. With coronavirus and these wildfires and the blackouts and this excruciating heat, I’m thinking of the words, “I can’t breathe.” And “I can’t breathe” is really coming from the same systems that have killed George Floyd, Brianna Taylor, Mario Woods, Alex Nieto, so many Black and Brown people around the world, so many poor people, disabled people. This phenomenon of colonialism has brought us to this point where we are now squeezed into this moment and our bodies are so deeply impacted.

And with coronavirus, I feel like finally there’s something that has exposed to everybody around the world the fracture lines of our societies and how the suffering of Black, Indigenous, People of Color and Poor people is built into the architecture of our world, the world that was created through colonialism. The ways in which our societies are structured, they cannot function without the enslavement of our bodies, and the enslavement of other beings for our benefit. And by other beings, I mean the plants and the animals and the water, all of these entities that are necessary to thrive and be in good balance.

And so when I think of medical sovereignty, I really think of a very deep decolonizing of our understanding of what our health and wellness is, and our understanding of medicine, and how to use medicine. My practice of Western medicine is part of that same colonial project. So when I hear people at UCSF talking about health equity as if like, yes, we want health equity.

Well, the project of medicine as a Western scientific enterprise — medicine was used as a tool of colonization, of colonizing people and places. Often Black and Brown people and Indigenous people around the world were only kept well enough to extract the resources of our home countries. We were never meant to be kept truly healthy in the ways that were determined as European health, let’s say, at those times. And so what we’re seeing right now, and that’s just even in this language and imaginings of saying, oh, we want health equity, we’re seeing actually it doesn’t exist. It never has. It was never part of the equation.

A paper just came out this week that showed that Black doctors taking care of Black babies, those Black babies have better health outcomes, and the way that the paper was framed is like Black babies survive better with Black doctors. The way the paper should have been framed is that the racism of white doctors creates death for Black babies — because that is what it is. It’s the interpersonal racism, it’s the deep belief that Black lives don’t matter which has been part of the colonial project starting 600 years ago. From looking at the carceral state to even the arrival of a sacred new being into this world, a baby. And so when we see that in those structures, it really gives us a moment now where people are starting to make these connections that they were not making before and starting to ask, how did we get here and what can we do differently?

So when I think of medical sovereignty for all of us, I think of really finding a way to dismantle those structures within our minds, within our understandings, within our social structures and within our bodies to create the possibility for health. And by that, I don’t just mean health of our one self, our individual health, but health of our communities, health of our families and health of our relationships with all the entities that make health possible, which means the air, the water, the life all around us.

And so with coronavirus, this has really been an interesting moment where people have been talking about social distancing. And I have been spending a lot of time in a forest. Sadly, that forest is now on fire because of mismanagement from colonial practices of fire suppression. But in time with that forest, in this beautiful pool where these salmon babies, these coho salmon were growing, I shifted my understanding that what I’m doing is not socially distancing so much as creating my sanctuary with my family with all the other entities that sustain and enrichen our living.

This virus will be with us for quite some time. It will not go away any time soon. This is going to be the way we have to move forward. And so it really gives us an opportunity to think about how we want to structure our social lives, because we are social creatures and we need our community. How we structure ourselves to create those sanctuaries and really redefine those sacred relationships that keep us healthy and well, and then how do we prescribe those limits.

So I think that medical sovereignty for me is deeply about understanding the nature of how we got here, and then how we can create new structures that can make these other ones obsolete — from our food systems, from how we grow our food, to how we relate to our food and our seeds, to how we relate to each other.

One of the key things for our European friends who are on the line right now and with us is really looking at the violence of this concept of whiteness, how it was constructed in order to oppress others who were not white. And I think about this right now with the United States, because so much intensity is happening right now, it’s polarizing. And this is really having an impact on people’s health. I challenge people to really think about how we can dismantle this concept of whiteness and tie ourselves back to our own ancestral lineages, how we can dismantle false notions of supremacy so that we can better integrate into a fabric of life together..

So this concept of medical sovereignty is going to differ for everybody, but I think it really is about creating a sanctuary. That’s the brief answer.

Lyla June: I encourage everyone to Google Rupa, look at her YouTube videos. She has a wonderful one on white supremacy as a public health problem. Supremacism in general, male supremacy. So please feel free to explore her work more.

Mona, if you’d be open to sharing the same, How do you feel in this time? What is sovereignty? What could you share about sovereignty to all of our sisters and siblings here today?

Mona Haydar: Thank you, Rupa. That was just very enlightening. I am somebody who talks a lot about colonialism as a person of Syrian origin, whose people have been impacted by French colonization, European colonization, and I am sitting with that more so now than ever. That colonial wound has really referred me to the reality and to the fact that I cannot become truly sovereign, truly liberated as a human being if I continue to externalize my enemy, and to hate.

This is a difficult thing for me to articulate. But basically, I want to be liberated and I want to be sovereign as a being. And I have trouble with the dualism, the dualistic nature of externalizing the enemy. And I am attempting as a spiritual person, as a religious person, to see that which hurts me and to see the way that I reflect that back out into the world, the way that I perpetuate those trauma loops and cycles.

And so for me, as I grow, as I age — I’m a mother of two children — as somebody who has now entered my thirties, who sits at the feet of elders, I’m learning more and more that I have to harmonize that which is within me first. And when I balance that — when I love the parts of myself that are wounded, such as the colonial wound that I have — I become an agent of healing, inside the pain creation models of this world. And so I’m starting now to open my eyes to the truth, that as an artist, opening my heart to something like this virus and saying: I see you as something of this Earth, something that exists here. What do you need and how do I heal you, and how do we love you enough to stop hurting us?

I feel the same way about white supremacy. What is lacking in the nature of white supremacy? What is so pained inside of that existence that it can’t help but hurt and destroy the world? And I’m sitting with that. These are ideas that come from a spiritual tradition of Tasawwuf, of Sufism — the mystical practice of Islam —of seeing ourselves not as dominators of the Earth, which is a product of Empire’s religion. I have a master’s degree in Christian ethics. It’s not in the original project of Christ, of Christianity. It is in the original project of colonialism, of empire, which seeks to dominate the world. This Dominion theology is destroying us, that we are separate from the Earth, that we are separate from our enemies, that we have something different than them. And so we will rise separately. And so we will overcome. And the only way to truly overcome and to truly become sovereign is in ceasing to externalize the enemy and to create balance and harmony within us.

And that, I think, is the most radical thing possible, because when we join together and we are harmony makers in the world, we stop needing empire, we stop needing the garbage of corporate capitalism, unfettered capitalism. We stop buying their waste, their garbage, as things that we need. We stop commodifying our own lives. And when we do that, I think we become radical agents for true liberation and sovereignty. And that’s why I think we are conditioned to see an external enemy. We are conditioned to struggle against and not struggle together for collective liberation.

Again, I know this is like big and wide, but I do believe that when we cultivate internal harmony and balance and healing, we become agents of collaborative sovereignty, which I believe is the ancient way. I mean, we only survived to this moment by helping each other, not by competing with each other. So I’m so glad for this opportunity to talk about these ideas together and to work together to build the world that we all can see with our heart’s eye. In my tradition, we believe that the heart is that which truly sees. And so we’re building that together, I think, with our heart’s eye.

Lyla June: Wow.

Mona Haydar: Love you, sis.

Lyla June: Thank you so much for sharing.

And Rebecca, and then Sarawi, you’ll come after Rebecca. Thank you so much for joining us. The work you do is so beautiful and I’m so grateful that you’re here.

The government isn’t taking care of our relatives with disabilities. And as you taught me, a lot of us actually have disabilities that we don’t fully understand, that we are a part of that community. So please share whatever you’d like to share on the topic of sovereignty.

Rebecca Cokley: Definitely. Thank you so much for having me here. I said it earlier, but this conversation is amazing.

I’ve been thinking a lot about what Rupa said around health equity, and it’s a concept that is a real struggle for people with disabilities because how do you get to health equity and a framework that includes disabled people when we are seen as the problem that needs to be solved, versus a valuable contributing member of the society itself? What does it mean when the Americans with Disabilities Act turned 30 less than a month ago and there are still 80 percent of polling places in this nation that we can’t access to be able to cast a vote. And we are 70 percent unemployed and we are the majority of people in poverty in this nation.

And so it’s a real struggle. And at the same time, I think the conversation around “I can’t breathe” is really powerful. And for Eric Garner and many of whom have said it, I mean, Eric Garner had asthma. Saying “I can’t breathe” is a declaration of disability, which is protected under the law, and to our community the roots of ableism — and I included the definition that we use for ableism in the chat, and racism — are connected to the same tree. I mean, when you look at early policies around the controls against African-Americans in this country, they’re grounded in [00:42:31] phrenology and drape Tasmania. [00:42:34] They pathologized slaves with disabilities, whether or not they actually had them, as a justification for keeping people enslaved.

For my people, for Little People, we were bought and sold and bred across carnivals and circuses and beyond even just Little People, but people with disabilities in general, we were bred to be entertainment. And even though my lineage doesn’t go back that far, I have cousins who can trace their family lineage back to Vaudeville, back to the sideshows. They know when P.T. Barnum bought their grandfather and their grandmother and forced them into marriage.

I think the coronavirus for us as a community is one of those moments where — I don’t want to say we told the rest of the world so, but we told the rest of the world so. We started mourning our dead in February. We knew that our people were going to die the most. And as it is, two thirds of the people that have died are people that either live in or care for people that live in institutional settings. We still live in a society where we’re so uncomfortable by our disabled brothers and sisters that we ship them off somewhere else, versus caring for them in our homes, versus fighting for the right for disabled and aging people to live at home with their families, with the services that they need.

We’re prepared to see the biggest boom in this country, in the world, of disabled people that we have seen since AIDS and HIV in the 1980s. As a community we are welcoming our brothers and sisters who are going to have long-term disabilities because of coronavirus. And we know that that’s an impact. We know that people are ending up paralyzed, people are ending up with organ failure. And we don’t see them as weak. We don’t see them as a burden.

Our movement elders were the children of polio. The woman who is responsible for my family getting an education was denied the right to be a kindergarten teacher because she was told her wheelchair was a fire hazard. And so where people see burdens, where people see pity, we see the potential for strength and power. And in this moment and in this time, I really do believe that there is fear and fear is tangible. There is also hope — and I am endlessly curious about the impact of the Coronavirus Generation, what they have seen, what they have lived through, and the strength and the potential that they have for showing — not just here in the United States, but globally — a different way for how we should be living as a society.

Lyla June: Thank you, sister, so much. I’m grateful that you’re here. I’m very honored. Bueno, Sarawi, mi hermana, my sister, what would you like to say about this? Tell us about the work you do in Ecuador.

Sarawi Andrango: If you want to talk about sovereignty from multiple points of view that you are sharing from your spaces of resistance, to all the comrades, to talk about the women and the people that are on the front lines of disability and to have access to medicine. Also to remember ancestral medicine and to talk about the right to our own spiritualities in our own territory, with our freedoms. We the artists form a circle, like a little nucleus packed with content. And what do we do is to focus on this theme of colonization and sovereignty, and we transform that into music, painting, poetry, and we disseminate it around the world.

To be honest, here in Abya Yala, in Latin America, as in many other indigenous nations, our indigenous artistic expressions are the result of the transmission of the oral traditions that have been transmitted to us, that have been given from generation to generation. More than a written tradition, the philosophy and all the cosmology we transmit through the music, through the dance, through our songs. Our songs are to our seeds, to the water, to the air, to the rain. And all this is what colonization has tried to silence. This (colonized) way of communication presents our artistic expressions as something like entertainment, something like a folkloric spectacle.

In this time of the pandemic what we are seeing from the ministries of culture is an attempt to overshadow what is now happening in our territories in terms of extractivism, mining, deforestation, agricultural extractivism. All of this is what we are working on through art in Ecuador and in Latin America, where a network of artists — women especially — are working. But of course they take away the public spaces, they take away the budgets, and so we are working to form networks like this one where we can dance, paint, sing about the things that Rupa and Mona and Rebecca and Lyla have spoken. Art is the tool we use to exercise sovereignty of the individual and collective, community rights. We hope that this will end in a decolonization of all aspects.

Lyla June: Many thanks, and please share your Facebook in the chat so that we can see the work you are doing there in Ecuador. She sent me some of the music videos that are making, some of the art that they’re creating, and as a as a fluent Quechua speaker, that’s a big deal.

So, I want to take a moment to thank each and every panelist. Thank you, Rupa. Thank you, Mona. Thank you, Rebecca. Thank you, Sarawi. It truly is a blessing to have you all here as leaders. We’re all leaders here. That’s one thing I was thinking was, if we could have all of you as panelists we would — but there’s just too many of us. So thanks, thanks to you all for your work.

Cheryl Angel LaDonna Allard Lyla June Johnston Mona Haydar Rebecca Cokley Rupa Marya Sarawi Andrango Sovereign Sisters Sovereignty Standing Rock

this so beautiful thank you for sharing.

I registered and wanted to attend – but the technology was too confusing for me, so thank you for this article. I hope one day to be able to participate and my passion is the walk the ancient path of knowledge in order to help make this world a better place. I also want people to know more about who Native Hawaiians really our – our history is not know such as the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom by the U.S. I suspect more than 50% of Native Hawaiians live off-island and our children do not know who we are. There are no specific ethnic studies departments other than on the islands, we are lumped in under the category of Asian and Pacific islander and remain invisible. I was born on the islands of Havai’i before statehood. There is much to share and learn. He Havai’i Au, fay

Thank you so much for this feedback Faye. We will be in touch. Pamparius. – Tracy