Story and photos by Tracy L. Barnett

For El Daily Post

While most people were celebrating the holidays, others from Canada to Mexico mourned the loss of a leading Wixarika scholar and teacher, a cultural ambassador and an indigenous activist whose work on behalf of indigenous unity spanned North America.

Yuka+ye Jesús Lara Chivarra’s path took him from the Huichol Sierra to the halls of power. He hobnobbed with rock stars and artists, he faced down police and corporate executives, he taught college students, film producers, attorneys, journalists – but he was always most at home in his village.

Yuka+ye Jesús Lara Chivarra’s death in December after an automobile accident came as a shock to all who knew him. The tireless traveler, writer and public speaker touched countless lives during his 54 years, including this reporter. Lara Chivarra was an educator by training, a teacher and the author of a Wixarika-Spanish dictionary. He worked within his community to keep his culture alive and at the same time worked to make his language and culture accessible to those on the outside, even developing a method to teach the arcane Huichol language more easily.

He was one of those at the forefront of the movement to save the sacred territory of Wirikuta from Canadian mining companies, and he traveled extensively in the United States and Canada to garner public support for this cause. It was in these travels that he gained the most public exposure, but his work in defending Wixarika territories began nearly two decades earlier.

Jesús González de la Cruz, a friend from his early days in the sister community of Tuxpan de Bolaños, remembers him as a clear and eloquent thinker even as a youth. He recalls him presenting his ideas to the general assemblies while still a college student.

González de la Cruz would go on to accompany his friend and tocayo (a person with the same name) in the struggle to recover and defend Wixarika territories for their communities, including an unforgettable standoff at Mesa del Tirador in the late 1990s. The federal government had identified 14 focos rojos (trouble spots) throughout the country, and Tuxpan was one of them. González de la Cruz was serving as a delegate of the Unión de Comunidades Indígenas while Lara was president, and he remembers the young leader as a force for calm and reason.

Lara Chivarra was serving a term as commissioner of public lands in his home territory of San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán, high in the Western Sierra Madre, and also as president of the Unión de Comunidades Indígenas Huicholas de Jalisco.

Carlos Chávez of the Jalisco Association in Support of Indigenous Peoples (AJAGI, for its initials in Spanish) remembers that time, around 1997, as tense because of a struggle to recover thousands of acres of Huichol lands invaded by non-indigenous neighbors. A group of Huicholes occupied the lands and refused to leave.

“The governor of Nayarit sent in police and it was at the point of getting really ugly,” Chávez recalls. “The federal government intervened and officials arrived in a helicopter; they weren’t going to leave until the issue was resolved.”

Lara Chivarra was the chief negotiator for the Huichol communities in that confrontation, and thanks to his level head and his skilled diplomacy, he was able to help avert violence. The negotiations eventually led to the recovery of more than 22,000 hectares of land for the territory of San Sebastián.

“That’s when I realized that Don Jesús was an exceptionally intelligent person,” Chávez recalls. “He was able to direct in a very intelligent way the strategic struggle; he quickly captured the principal points in any struggle and would form a clear position.”

That struggle would further the agrarian battles throughout the region in the years ahead, said Chávez, leading to the recuperation of thousands of hectares of lands for various Wixarika communities. Lara’s eloquence and strategic thinking would go on to make him a leader for his people and for indigenous unity efforts throughout the continent.

“He will always be a great example,” said Chávez. “I always admired his capacity to observe reality, deeply, and then act. … He was a person who, upon knowing that Don Chuy had arrived, we could relax because we knew a force had arrived, that everything was going to be all right.”

Human rights attorney Alfonso Hernández Barrón of the Jalisco Commission on Human Rights, another longtime friend of Lara Chivarra, observed the same characteristics years later at a public hearing in Real de Catorce, in the sacred territory of Wirikuta. Lara served as a member of the Wixarika Regional Council, a group that formed in the beginnings of the struggle to save Wirikuta, as well as the Wirikuta Defense Front. More than 100 people had gathered and rumor had it that the mining company had paid many of them to come and instigate.

“Suddenly they began to shout and threaten us,” said Hernández. “I remember that I personally was feeling really indignant, but Jesús Lara was at peace. At no point did he seem to be bothered. We had some difficulty leaving because we felt our physical integrity was being threatened, but Jesús Lara kept calm.

It was in this context that he was commissioned by his tribal authorities to represent the community in trips abroad to explain the urgent need to protect Wirikuta from mining operations.

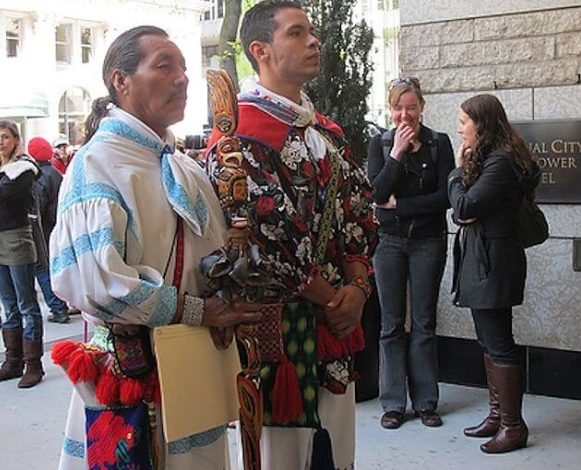

I accompanied him and the rest of the Wixarika delegation on several of those trips as a translator – first to Cancún for the COP 14 climate talks, and later to Vancouver, British Columbia, where he met with First Nations leaders and spoke at a conference on mining justice. It was there where he faced down his nemesis – together with Huichol artist Cilau Valadez – when they entered the First Majestic Silver Corp.headquarters building to meet first with the corporation president and later to present their statement against the mine at the annual stockholders meeting.

The scene was, again, tense, with interventions by police, this time in the imposing tower of the mining company. I will never forget his impassive figure, head high, facing the gilded doors of a foreign giant, holding the carved wooden staff of the late actor and indigenous leader Chief Dan George, presented to him for the purpose by his grandson, Tsleil Waututh leader Reuben George.

Most of Lara Chivarra’s activities were, however, of a much calmer sort. Hernández Barrón met him years before in one of many general assemblies of the Wixarika government, and they continued to meet, both in the assemblies of his home community of Ocota de la Sierra and in other communities throughout the extensive Huichol territories.

They began working together on human rights topics, particularly related to indigenous rights and education, and began to develop a deep friendship, Hernández Barrón said. Their first project together was a series of visits to housing units at the regional schools, where students who traveled from faraway communities and settlements were able to stay.

Lara was requesting funds from state agencies to equip and expand the substandard housing situation, which he was eventually able to procure, with Hernández’ help. Lara also worked with state agencies to revise the school curriculum to be more in harmony with the Wixarika cosmovision.

For Hernández Barrón, however, the most important project they accomplished together was a series of visits to the most important sacred Wixarika sites, beginning with the Pacific coastal site of Haramara. Here they witnessed destructive encroaching development and costly transport fees for Wixarika pilgrims who wished to make their offerings to their deities.

This was the place where, according to the ancient Wixarika creation story, the first people came out of the sea, touched ground and began their long journey to the westernmost pole of the ancient Wixarika universe, Wirikuta: Birthplace of the Sun.

At each of the sacred cardinal points of the Wixarika people, the story was the same: environmental and cultural degradation, destruction of offerings, impediments to access and other problems. In that process, Hernández says, Lara Chivarra became his teacher, entering with ever-greater depth into the mysteries of the intricate Wixarika culture.

Together they prepared the first report for government agencies and the public, which began a series of actions leading to greater public awareness, changes in policy and funding for the protection of the sites, and to facilitate access for Wixarika pilgrims.

“It was a cutting-edge document,” said Hernández. “No one had ever made a pronouncement in favor of the protection of the sacred sites and in this work the consultancy and the willingness of Don Jesús Lara Chivarra Yuka+ye was fundamental.”

These journeys took place in 2010. Five years later, at the last assembly meeting where Hernández saw his friend speak, once again, about the urgency of protecting the sacred sites, the two of them made a plan to carry out the same journey, returning to each site to evaluate the current status. Hernández has resolved to make that journey and produce the report in Yuka+ye’s honor.

During that same year, the threat to Wirikuta from mining companies emerged and Lara Chivarra was one of a number of Wixarika leaders who began appearing at public forums, traveling around the country and beyond to plead for support of their cause.

“In this project Don Jesús Lara Chivarra was a tireless warrior,” said Hernández Barrón, who accompanied his friend to forums in many cities. “With his firm voice and his clarity of ideas, he was a fundamental factor in helping people understand the dimension of what Wirikuta means for the Wixarika people.”

Indeed, the high arid semi-desert of Wirikuta is the Wixarika equivalent of the Basilica of Guadalupe, as Lara Chivarra was fond of saying; and just as the Mexican people would never consider sacking the highest altar to the Mother of God, they should never contemplate the destruction of the birthplace of the deities, the place where the ancestors reside, and where his people travel in their annual pilgrimages to leave their offerings, collect the sacred Hikuri or peyote cactus that connects them to those entities, and to receive guidance for their lives.

Thanks to the efforts of the Wirikuta Defense Front and other civil society groups of which Lara Chivarra was a part, an international mass movement formed to support the Wixarika defense and a legal team won a judicial moratorium on the mining project, though the project is still being litigated.

Yuka+ye the artist

His work on behalf of Wirikuta would lead to strong friendships in many places. Among them was Paola Stefani, an anthropologist, writer and filmmaker who coordinated communications for the Wirikuta Defense Front for a time and then went on to become the producer for the Hernán Vílchez film, “Huicholes: The Last Peyote Guardians.” Lara Chivarra appeared briefly in the film. He would go on to appear much more frequently at Stefani’s ample home in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma, which became a landing point for Wixarika leaders and activists throughout the campaign.

Lara Chivarra stayed with Stefani and her son Iván for a month to work on the publicity campaign and the two became fast friends. Iván loaned Lara Chivarra his palette and brushes and he began to paint scenes from his beloved sacred lands. Soon he and Stefani were painting together, a sweet respite from the rigors of their political struggle.

In truth, Lara Chivarra had painted for years; one of the first memories of Martín Carrillo Vázquez, a student of Lara Chivarra from his neighboring town in the sierra, was a mural of a deer in the elementary school where he attended. The deer was accompanied by an eagle and a tower, and hand-painted words in Wixarika. The artist: Jesús Lara Chivarra.

“He was the first Wixarika companion with whom I shared on a daily basis and he was the one who taught me about the Wixarika culture … Jesús was my teacher,” said Stefani. “I worked at home, so we could pass the whole day together doing things.”

In addition to painting, Lara Chivarra wanted to work on his dictionary. Stefani gifted her new friend a laptop and he set to work. A good part of his book, she said, was written at her house. And when the Huichol documentary was finished, she asked Jesús if he would watch it.

“I showed it to him so he’d give his opinion, which was fundamental for us, since he had formed part of the process, and was my advisor from the beginning,” she wrote. “I was very nervous when I showed him the film. At the end he congratulated me and told me that this documentary had to be shown all over the world, and he accompanied us to the first press conference, which was an honor for us.”

As with many of Lara’s friends, the two had plans for the future: to make a trip to Wirikuta to paint some landscapes.

“His death was an extremely hard shock in my life. I can’t believe that he is no longer with us,” she wrote. “Jesús taught me that one must work for what one believes in and what our hearts tell us. I will miss his words and his laughter. Jesús was a man with a great heart.”

Yuka+ye the father

Lara Chivarra was the father of 15 children with two different women, consistent with Wixárika custom.

“We lived together, there was no problem,” Saria recalled with nostalgia. “We all love each other a lot.”

Lara’s loss leaves a huge void in his family. Contacted by telephone, his daughter shared a few memories before dissolving in tears.

“We had unforgettable moments, with so many things that we shared,” Saria said. “I don’t understand why we were allowed to grow closer and closer each day and then suddenly to have him taken away from me in this way.”

The most endearing gift that her father gave her and that she will always wear with pride is the Wixárika name that he gifted her with in a special ceremony on the fifth day of her life.

“‘Wiwiema’, that’s how my father called me, which means flowering corn, because I was born in August, when the milpa blooms. That’s the most beautiful thing he gave me. ”

Yuka+ye the educator

Jesús Lara Chivarra studied pedagogy at the normal school of Nayarit and later the National Pedagogical University, and went on to become an elementary and secondary school teacher, work that he left behind to become active in politics; but he never stopped his work as an educator.

“He had a great capacity as a historian and linguist,” said César Díaz Galván of the University of Guadalajara’s Unit of Support for Indigenous Communities. “He always had a very strong interest in preserving the knowledge and identity of his people, and so he decided to put his knowledge within reach of anyone, not just people of his ethnic group but also mestizos who approached the community with the intention of supporting, and we were fortunate to publish some of his materials, which will remain as a legacy for posterity, as he had very extensive knowledge not just about the culture in general but also the transcendence of the meaning of the Wixárika people for the whole world.”

His book, “Wixarika Niukieya tsutua mieme: Principal words in Wixarika,” has served as a guide for many. At the time of his death, he was working on a new volume to help non-Wixarika speakers understand the language.

His efforts to promote the culture and attend to the rights and the needs of his people also led him to form bridges of dialogue with different government agencies. Díaz credits him with helping to lay the groundwork for the Office of Indigenous Affairs, now the Indigenous Commission for the State of Jalisco.

And despite his travels far and wide to promote a greater understanding of his culture in the world at large, he never stopped promoting cultural education in his own community and throughout the Wixárika territories.

“He worried a lot that the new generations didn’t understand and were losing the practices of their ancestral customs,” said Hernández Barrón. He promoted cultural education in the Wixárika school system and other projects to help Wixárika children and youth grow up inculcated in their tradition.

Lara’s collaboration with Hernández played a part in perhaps the most innovative and powerful educational initiative for the Wixarika people to date. In one of their innumerable travels together, around a fire in an all-night ceremonial vigil in Wirikuta, the idea for Project Niuweme was born: a project to train a group of Wixarika youth to be attorneys and human rights advocates for their people.

Hernández went on to found and direct the project, with the support of the Centro Educativo Nueva Cultura Social (CENCUS), and launched it with an initial class of 40 Wixárika youth from the sierra, 30 men and 10 women, including Saria Wiwiema, Lara Chivarra’s daughter. He became their teacher of Wixarika culture.

Now in its fifth year, the project will be graduating its last group of students, but without the presence of their spiritual and cultural guide.

“It was a very ambitious project, and now we have to finish without the presence of Yuka+ye,” said Hernández, “but we will have his spiritual accompaniment always, because he was the one responsible for the teachings of culture.”

Sofía Mijares, known by her Wixarika name Aukwe (Flower), was part of the founding class, and went on to ITESO to study communications. She remembers the first time she met Yuka+ye when she was researching sacred sites and interviewed him.

“I always thought he was a mestizo, I don’t know why – perhaps his face isn’t common among the Wixaritari,” she wrote. “But one day when I was sad, he gave me some encouraging words, and he spoke to me in Wixarika, which surprised me.

“He always counseled me as if he were my father, my grandfather, he never thought he was more important than anyone, he was always more of a friend, a brother, a companion, sharing his knowledge.”

Martín Carrillo Vázquez, another Proyect Niuweme student, had finished preparatory school without prospects of further study, and resigned himself to life as a traditional Wixarika farmer, when he received an invitation to apply for a scholarship.

“They were looking for people who were committed to their communities,” he recalls. He contacted Lara, who helped him get the scholarship. Now he is in the final year of training to be an attorney and he feels more rooted in his ancestral traditions than ever.

“I think that he planted something in me and in other students about the cultural teachings of the Wixárika people,” he said. “It was there that I began to reflect more deeply about what I am – from where we come, what we can do and where we are going.

“That’s what I learned from him …. I fell in love with my culture. Thanks to him I identify as Wixarika, and I will continue to do so, promoting and spreading and protecting the culture like him.”

Yuka+ye the cultural ambassador

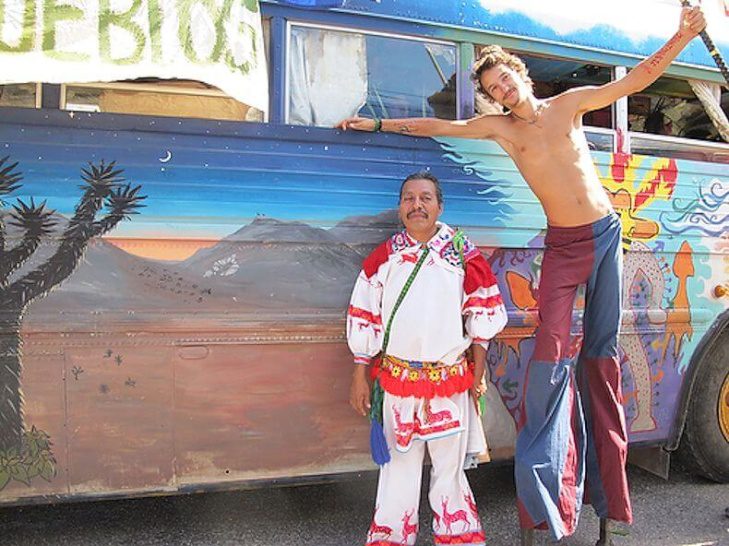

Lara Chivarra’s travels took him at least as far south as Guatemala, and at least as far north as Lillooet, an important First Nations site in the mountains of British Columbia. He met with First Nations leaders wherever he went and served as an ambassador to the Native American Church.

“From his lifestyle you could tell what kind of a person he was,” said Sid Mills, president of the Native American Church in the state of Washington and a friend of many years. “He was a soft-spoken man, passionate about his cultural ways.”

Mills, who was involved in the Vancouver actions of 2011 and helped organize a corresponding action in front of the Canadian consulate in Seattle, recalls that Lara worked hard with allies in the north to “develop a north-south solidarity platform and to develop cultural consciousness of our Indian ways.”

“What he taught me – and I think what we taught each other in the struggle – is to keep strong and don’t give up. He didn’t give up until his dying breath.”

Lara Chivarra touched many peoples’ lives in the North, as well as in Mexico, said Mills.

“We’ll be talking about Jesús for a good lot of years, maybe for generations,” Mills said. “He’ll be in the hearts and minds of our people. He’ll be memorialized that way. His legacy will be memorialized forever for the people here.”

In the words of his obituary, published on the website of the Wixarika Regional Council:

Yuka+ye was born on June 12, 1961. Activist, teacher, writer, thinker and wise man. Noble, simple and humble. Undisputed leader of firm conviction and a tireless warrior. Every day he promoted the struggle with his words, he responded to each of the tasks with which he was entrusted, he accompanied and followed every step of the defense of the Wixárika culture.

— Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer based in Guadalajara. She traveled extensively with Jesús Lara Chivarra as his translator and friend, and will miss him always.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

Huichol indigenous rights Jesus Lara Chivarra mining Niuweme Project Wirikuta Wixarika