By Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez

with production by José Antonio Calfín

photos from the Esperanza Project film “Legacy of the Andes”

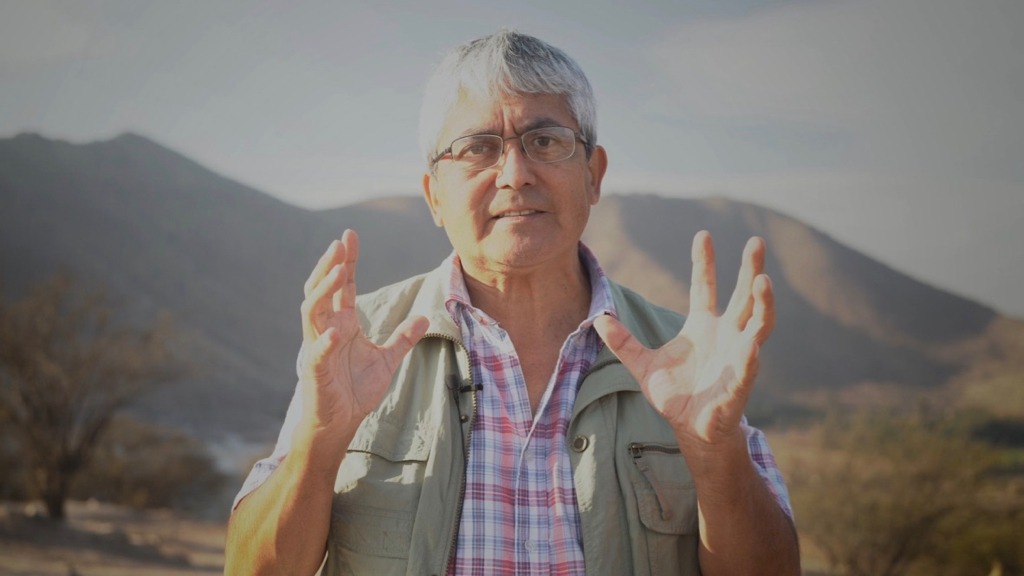

For the Mapuche people of Chile and Argentina’s Patagonia region — or Wallmapu, as its original inhabitants know their territory —, the warnings of the pandemic began in the form of a flower. When Mapuche anthropologist Carlos Painemal traveled through the territories, he kept hearing about it: The quilas were flowering. This type of bamboo only blooms once in a human lifetime, at the most, and for the elders, it’s an ill omen.

This story is a part of “Cosmology and Pandemic: Indigenous Responses to the Current Civilizational Crisis — Episode 2, Legacy of the Andes,” produced by The Esperanza Project with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The One Foundation. Watch the accompanying film, read related stories, download the PDF and explore the entire transmedia series here.

“From the sea to the mountains, I listened to people comment that the quilas were flowering. And when I asked what that meant, they told me it meant misfortunes, pandemics are coming, wars are coming, we have to prepare, families must prepare,” Painemal recalled.

Then came the eclipses: crossing Chile and Argentina were two full solar eclipses, one in July 2019 and one in December 2020.

“Eclipses are bad for Mapuche society because it is the death of the sun. But it is even more serious when there are two eclipses. Mapuche society knew that what was coming was bad.”

Lea esta historia en español — Los Mapuche: Sobrevivencia Cultural en el Sur

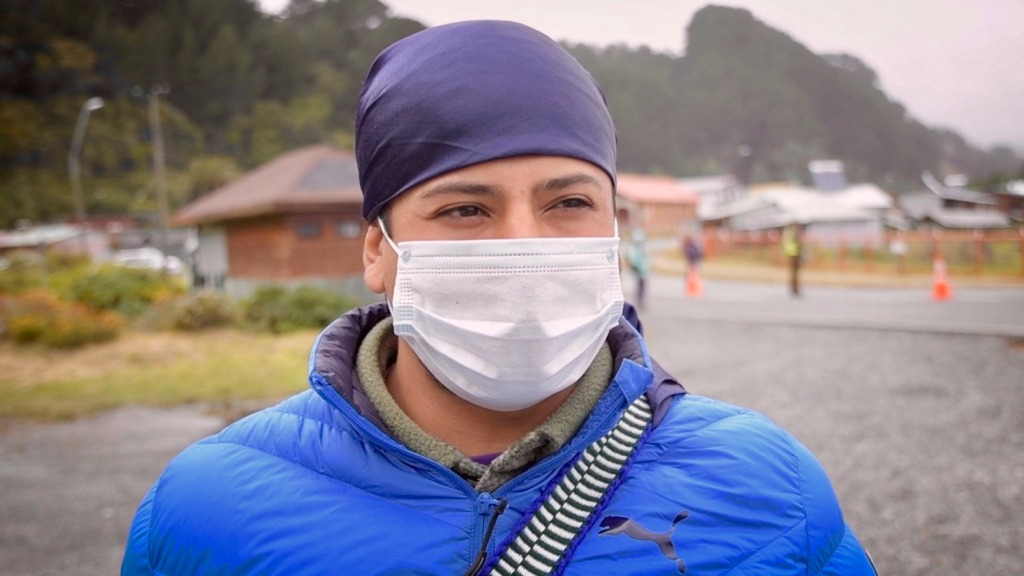

Sonia Millahual Cheuque, a traditional lawentuchefe or medicine woman from the island of Treke, Quele, Chile, was one of those who saw the pandemic coming – in the quilas, in the eclipses and in her peumas, or dreams.

“I hope to be able to save for the future with the little I earn,” she said, her dark eyes anxious under a flowered headscarf. “I see it uncertain because with this eclipse, the Lahn Antü (Death of the Sun) as they say, we don’t know what else this life prepares for us, right? But I don’t know if the people see it.”

Millahual found the trend of eclipse-watching and celebrations to be a reflection of the ignorance and lack of respect in modern society.

“I say that nothing good is coming. Everyone was happy because there were quila flowers. I said, that means ruin and disease, and this is what we are experiencing… I believe that both good and bad will come.”

Millahual, who was also the lonko or leader of her community and a teacher of the Mapuche language and cosmovision, interviewed by Cosmology & Pandemic producer Juan Antonio Calfín in December of 2020 said that her dreams were warning her to prepare herself spiritually for the times that were coming. But less than a year later, she was gone — a victim of the very pandemic she was fighting.

She prepared as best she could, collecting and storing her lawen, or medicinal plants. When the pandemic began, however, the Chilean government restricted movement and it became difficult for Millahual and other traditional medicine practitioners to gather their herbs and to visit patients. It was one of the hardest things she had ever experienced, she said, to not be able to do much to help her community during the time of the pandemic.

“I’ve been helping as much as I can with my lawen, giving people good medicine so they don’t get sick. Thanks to that my whole family is healthy.”

She was able to cure her 89-year-old mother of a severe bronchial infection. “She had a very ugly bronchitis, but she did not go to the doctor. I told her not to go because I would make her lawen, so now she is healthy.”

The isolation imposed by the government during the pandemic took a toll on Millahual and her people. The Mapuche consider their collective life an integral part of their existence, and as such, this pandemic and the social isolation involved present a particular challenge. Their word for community expresses the concept: the lof is a social unit that includes equilibrium and reciprocal relationship with each other and with the land that sustains them.

It is an essential part of their lives, especially in rites of passage like birth and death. The lof, like the Andean concept of ayllu, is not only a physical space, but a cultural and spiritual one, as well.

Millahual lost several loved ones to the pandemic, including her brother,, and the pain of losing them was deepened immeasurably by the inability to visit them during their illness or gather at the traditional wake.

“We can no longer watch over our dead, we can no longer do a ceremony, we can no longer visit our loved ones other than two or three people in a cemetery, and that doesn’t even make sense,” she said. “You have to mourn your dead at home, alone.”

Millahual’s own death was announced on social media on Aug. 10, 2021, by the Chilean Ministry of Culture, the Arts and Patrimony. She had been named a “Living Human Treasure” in accordance with UNESCO by the National Council on Culture and the Arts of Chile. The cause of her death, as reported to Calfin by friends and family: Covid-19.

Centuries of Resistance

Millahual’s death was tragically symbolic, given that the Mapuches have developed a powerful pharmacopeia of more than 500 healing plants through processes of trial and error over thousands of years. Indeed, a Chilean tree long used by the Mapuche known as the quillay tree was an ingredient in the first anti-malaria vaccine and ended up being used by the Novavax pharmaceutical company in one Covid-19 vaccine.

The effect of government repression on medicine people like Sonia undoubtedly influenced community resilience during the pandemic. “We still have not been able to fully dimensionalize the impacts,” said Painemal in a February 2023 interview. Traditional lawentuchefes and machis continued their work, though discreetly and not with the impact they might have otherwise had, he said.

The pandemic’s toll on the Mapuche communities was not as severe as people feared, he said, especially in the more traditional communities that still had a strong connection with the land.

The Mapuche concept of health goes far beyond the medical, according to Argentine ethnobiologist Ana Ladio. “It is something biocultural, and it has to do with social balance and natural balance. It implies a direct dependence on the health of animals, plants, mountains, and water. That is why the Mapuche people carry the flag in the fight against pollution, against environmental destruction, because they see it as disruptive actions of an imbalance that affects them directly.”

The very name “Mapuche” incorporates that idea (Mapu means “Earth” and Che means “person”). “The plants, the animals, the water, all the co-inhabitants (of the land) have a spirit, they have their own agenda. And if everyone is well, there is balance and there is health,” said Ladio. According to Mapuche medicine, each plant or element has its own agency, and cannot be manipulated at will. The medicine must consent to heal. And that longed-for balance and connection with Nature and with the lawen that is so necessary for good health has been increasingly elusive for more than a century now.

About 1.5 million Mapuches make up nearly 10 percent of Chilean society, the great majority in their southern homeland, Wallmapu — or, as most of the world knows it, Patagonia. An upsurge in violence in recent months, mainly based on conflicts over resource extraction in their territories, has tested the presidency of Gabriel Boric, the country’s first left-wing leader; his attempts to resolve the conflict through more than a year of dialog, and a new constitution giving more rights to Indigenous groups, went down in flames as voters rejected it.

Argentina’s Patagonia region is home to about 200,000 Mapuche. At its height, Wallmapu was a vast territory stretching across the Andes from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The Mapuche, the only indigenous ethnic group in the Americas that concluded a formal treaty and established a political boundary with the Spanish Crown, successfully resisted the Spanish conquest for more than 250 years.

The Mapuche maintained their sovereignty until Argentinian and Chilean independence; it wasn’t until the late 1800s that the governments of Argentina and Chile carried out a process of massacre and dispossession that in many ways paralleled that of the Western United States.

The Mapuche people have never ceded their territory, however, and now, more than a century later, conflict between the Mapuche communities and the government continues. Despite generations of violent repression, they continue the fight to defend their territory from mining and other extractive industries, and to keep their deeply spiritual culture alive.

“They are taking away our strength”

Healing is as much a spiritual process as a physical one, and different types of healers specialize in the different aspects.The lawentuchefe is a specialist in plant medicine, while the machi does his or her powerful healing work on the spiritual side, invoking the newen or vital energy to overcome the illness.

Working in family and community groups is important to the machi because he or she draws strength from the community, said Painemal. In both cases, strict government lockdowns and restriction in movement dealt a heavy blow to Mapuche healers, making it nearly impossible to practice in an effective way.

“The machi has the capacity and the strength, she has the newenes (the energies) to lead the search for evil in other spaces. There they fight with evil,” Painemal explains. “And for that, for the machi to have strength, what she needs is the community in order to fight that battle. And where the machi is in the healing process, the disease reaches the machi and the machi is the one that expels that disease.”

In particular it is important that all the members of the family lineage are there, to give the machi the necessary strength, says Painemal; but during the pandemic, that has not been possible.

Marcelo is a machi from the village of Rawe, near Temuco, who asked that his last name not be revealed, due to repression of machis and other traditional healers by the government.

“According to our Mapuche cosmovision, we base ourselves on laws that are universal, not earthly,” explains Marcelo. “We have to hold rogativas (special prayer ceremonies), we have to leave gifts for the Earth, we have to make sacrifices, we have to pray, we have to do many things in ceremonies.”

Primary among the ceremonial obligations of the machi and of the Mapuche in general is the Nguillatun, a powerful four-day collective prayer. The Nguillatun is carried out for many reasons – in part, to ensure that there will be good harvests, that the medicinal plants will grow, and that the animals and the people will be strong and healthy, explains Marcelo.

With Covid restrictions in Chile, any gatherings, including religious ones, required a permit; and permits for rogativas and nguillatuns were usually denied.

“When we do rogativas, when we do nguillatun, we ask for rain, we ask for peace, for harmony, for synchronicity with the universe, with the cycles of the Moon, with everything. So every time a permit is rejected, for any ceremony or any ritual that is important, they are weakening us, they are just running over us.

“That’s what hurts the most, that they want to take away what is most important to us — the right to keep our culture alive, to observe the Universal Laws.”

At the same time, people were stuck at home in front of their televisions, exposed to a constant drumbeat of danger, Marcelo observed.

“They spread fear through television. So people are increasingly detached from beliefs, they cling to fear a lot and they are losing faith, which is the most important thing in our worldview.”

One particularly difficult issue for traditional healers in rural areas was that the government required individuals to go online during quarantines and register their comings and goings using the Internet — a scarce resource in rural Mapuche communities.

For lawentuchefes like Panchita Calfin, who carries a powerful medicine lineage going back generations, this was impossible; she knows how to read the landscape like a book, as well as the symptoms of an ailing patient, but she cannot read Spanish. Even if she could, she has no Internet — so every time she left the house, she risked harassment from the authorities or even arrest.

“In many communities, there is still no access to telephone lines,” explained Panchita, interviewed in October of 2020. “I don’t know how to handle technology, so no, I couldn’t get permission, I couldn’t say I’m going to that place. And I, who am a medicine woman, I have to take the medicine when they ask me to and I have not been able to go to visit my patients in other places.”

So instead of being able to step up and help with the crisis, the lawentuchefes were pushed back into the shadows by the Chilean state. “I could be helping and bringing medicine, but instead I remained locked up here,” said Panchita.

During the six months that she was on lockdown, she stopped seeing her patients, Mapuche and winka (non-indigenous) alike. “I had patients who were getting better… some were already discharged and many receded from their illnesses, but now they were suffering a lot. Asking please that we don’t leave them abandoned, that we can please go there. But how can we do it? So I tell them, ‘I don’t know how to get to you, but the prayer is there.’

Panchita suffered greatly at not being able to go treat her patients.

“I am very sorry that we are not within the winka system. So it’s that how it is, we kind of left them all abandoned, and whatever God wants to happen. But it’s such a pity that my patients cannot be taking the medicine when we have so much good medicine. I just would ask that the traditional medicine people can be recognized in this state system, that we can deliver the medicine and be freely recognized and that we can help each other.”

Covid: A ‘winka’ disease

Argentine Ana Ladio, an ethnobotanist who has worked extensively with the Mapuche people, explains that for the Mapuche, coronavirus is just history repeating itself.

“The Mapuche associate the coronavirus as being a ´winka disease.´ Basically it’s part of their experience, since in Mapuche history they have suffered successive pandemics such as smallpox, typhus, and the black plague, and they have been able to realize that they were associated with the arrival of the white man. But it is not only the arrival of the white man himself, but the arrival of that relationship, inharmonious with nature, in their territory,” says Ladio.

“So that’s why there is an experience that, ‘We have already lived this,’ as many say. And obviously it is associated with these models that are totally disruptive, out of balance.”

The Mapuche society’s greatest strength in confronting the pandemic, according to Ladio, was its ethical vision based on solidarity, reciprocity, and complementarity.

“So, what has been done in this pandemic is to try to reinforce those ethical precepts,” she said. “They have used the virtual media very strongly for the communication of messages, for example, the call to preserve themselves in the territory, to stay in the territory, to return to the territory. The call to return to the lawen, that is, to medicinal plants. The call to cultivate the land, to recover the seeds, the call to help each other.”

Although a large part of the Mapuche communities have very limited access to the Internet, it still played a key role, according to Ladio, especially in terms of reaching out to the young people. Numerous digital radio stations were set up where traditional knowledge was transmitted. Music and Mapuche poetry were shared to provide people with spiritual accompaniment. The virtual media allowed a degree of organization, it allowed the communities to share information on how each of them was getting along.

“It was really a tool that was incorporated, which does not mean that they did not use it before, but suddenly it became key,” she explains. “And I think this is one of the capacities of the Mapuche people — which explains their capacity for resistance.”

The concept of healing with plants is quite different in Mapuche society, according to Ladio. “Lawen can be defined as a medicinal plant, but perhaps that definition falls short, because it is not simply a remedy, an element, but rather a living being; it has a spirit,” she says. “So the lawen is really a being that helps people with their health, who is asked for permission to use it, who is thanked for its beneficial uses and who has its own agenda. The lawen, if it finds that the person has complied with ethical precepts — of solidarity, of caring for the land — it offers healing. Some talk about plants being witches… They know if they are going to cure or not. They have their own agenda for the Mapuche people. So this is something very interesting and makes it very difficult to equate it to a concept of medicine as we know it in Western society.”

Fighting for Cultural Survival in Huampoe

Silvia Navarro Manquilef is a native of the community of Huampoe, in the Curarrehue region of Southern Chile, and a kimche, a teacher of traditional Mapuche language and culture. Together with her daughter Katerin and a handful of other women she is working on a reforestation project and to restore a small tributary to the Huampoe river. The community has been dramatically affected by the installation of the fish farming industry, where the majority of residents now work. The river that was once sacred to them, that was their source of water and food and connection, has been contaminated. The mallines, the rich wetland ecosystems native to the region that were once a great source of lawen, are filled with trash and are burned and drained.

“There has been a territorial abandonment here,” she says. “Unfortunately, the fish farming companies arrived here more than 20 years ago. And what happened? The first cause is that part of nature was destroyed, the natural spaces. The rivers were polluted. And in turn, by polluting the rivers, cattle, sheep, cows, and the lawenes that grow on the riverbank also began to be damaged. They have been deforesting, and there are some who set fire to burn the quila plants. They cut the trees in the summer, totally ignoring what a wetland means, the maintenance of water in an ecosystem.”

Silvia, the daughter of a lawentuchefe, grew up deeply immersed in the culture, and remembers well the river as a central feature of community life in her childhood. “We had a social life; we went to the bridge to see people go by. We would swim to the neighbor’s house, to play with the neighbor’s boys. We played, we bathed, we drank water from the river.”

People used the river to fish, to wash their laundry and the vegetables from their garden. “And now it can’t be done because it’s contaminated, it’s rotten, that water,” she laments. “It makes me sad – and it also makes me very angry that there are people who sold themselves to the fish farms.”

A neighbor who is an evangelical minister was opposed to the fish farms and they fought the industry together for a time. But the company offered him compensation for the damage to his land, and promised to pay him every year. Soon he stopped complaining and built a house with the money. Now he has three houses, two pickup trucks and three cars, she says, and doesn’t have a problem with the fish farms.

The growing presence of evangelical churches has done much to undermine the culture, says Silvia. “They forget to speak our language, our Mapudungun, they are ashamed. They even say ‘I’m not Mapuche’, but they carry the last name. But speaking the language, and practicing the cultural life, as our elders did in the past, that is something demonic, it is something that is embarrassing to them, something very ugly.”

Silvia sees the hope for her people in the next generation, and she does what she can with the children who come to her classes to build up their knowledge and sense of pride in their culture and their connection with the land. In Silvia’s class, everything begins with a territorial perspective of the family — and the community the family is a part of.

“Who is that family? How did that family live in the past? And what can we do to strengthen that family? So the family can go back and recover the practices towards the cultivation of the seed, the cultivation of empowering oneself again in small practices,” she says.

The school has an orchard where the children learn, and there is a space for medicinal plants, a space for flowers, and a space where they plant vegetable seeds: squash, broad beans, peas, corn, lettuce. The children learn to plant, water and weed their garden space, and they even learned how to prune. Silvia works with a veterinarian who takes the children to observe when he’s treating an animal at a neighbor’s farm.

They also do wildcrafting, going up into the hills to harvest pine nuts and berries, observing the differences in the terrain. The children document everything in their journals, and everything is recorded on video, so at the end of the semester they have a record of everything they have done. And the garden is a year-round project, so they are able to harvest what they sowed in the spring.

Silvia also teaches the children the ancient Mapuche practice of the trafkin, a traditional barter market. In years past, the trafkintun or trafkin was a means of connection, a place where affinities and friendships were exchanged along with seeds and produce, tools and artisanry, and anything else that people wanted to trade. These swap meets were interconnected and were essential to the Mapuche way of life.

“It is not only changing potatoes for wheat, but also who I am changing with,” she says. Trading face-to-face establishes a relationship. “Now I know him, I know where he comes from, how he works and he also gets to know me, and he learns about my territory.”

Katerin has seen a notable change in the children in the six years that her mother has been teaching at the school. “The vision of the children has changed a lot, because they have learned a lot,” she said. “They have learned to rescue what their parents do not teach them at home and they have learned to identify many things in our mother tongue, which is Mapudungun: birds, remedies, plants, everything. The seeds, too.”

She also tries to transmit to the children, and to anyone who cares to listen, the importance of the medicine of the ancestors, including the water, which is the most important medicine of all. Despite the contamination of the river, she keeps that communication alive. Sometimes she says to her dog Cicerón, ‘Let’s go. I want to talk to the river.’ And I get there to the bank and I stand there and I speak. It’s as if I was speaking with a being superior to me, someone that is still there, that hasn’t been intervened, and its waters go down, pure, fresh, and very cold. And it’s like there’s a connection…water is something I respect very much, and you don’t play with that.”

Projects like Silvia’s are increasingly important in the context of what Tomas Ibarra, a researcher with the University of Villarica, calls “the death of experience.” Ibarra has lived in the region not far from Silvia for 15 years, and has witnessed an increasing nature deficit not only among the urban populations, but even among the rural Mapuche people, and the pandemic exacerbated that trend, with isolation and screen time becoming the norm.

“Nature deficit is a phenomenon that has been described on a global scale, and refers to the fact that today human beings, society in general, but particularly children, are having fewer and fewer direct interactions with nature, touching, feeling, smelling, tasting the biodiversity that surrounds them.”

In rural areas, Ibarra points to the increasing use of technology in the home and the educational system. Among the processes that have triggered an extinction of experience, he says, are, “the fact that we are increasingly urbanized societies, that we are highly technological, that children are highly programmed, scheduled, responding to school systems that are alienating them from the nature of their environment.”

The extinction of experience not only refers to less interaction with nature and with biodiversity, says Ibarra, but also less interaction with history, with cultures, with narratives, with the grandparents. “It is the extinction of the biocultural experience,” said Ibarra.

Silvia’s group is one of many across the territories that are holding the line against the rapid advance of urbanization, laying the groundwork with the young ones to value the biocultural heritage that is their legacy as Mapuche.

“If we recover our land, we can sow our seeds, and if we sow our seeds in our own territory, we will be cultivating, we will be producing healthy food. And that is also less consumerism towards the market… creating an economy proper to a place, a lof, a community, and ideally, every Mapuche should have that awareness. Having culture and food go hand in hand.”

To Painemal, the integrity of the Mapuche culture, and that of Indigenous cultures around the world, is a key to the future — and in Chile, that fact has become apparent to a major portion of the population that has become disillusioned with the materialism and individualism of Western culture.

Deeply symbolic was the wenufoye, the Mapuche flag, as one of the most visible symbols of resistance in the “Social Explosion” that shook the nation from late 2019 until the onset of the pandemic. In one emblematic photo that went viral, there in the epicenter of the uprisings in Santiago’s Plaza Dignidad, what waved overhead between the barricades was a Mapuche flag.

“In these moments of great tectonic transformations and profound change, I believe that Mapuche society can make a great contribution to the West,” says Painemal. “Western Chilean society is in decline; their God of Father, Son and Holy Spirit no longer serves them, they no longer respect him. They are in search of other gods and that is why they go to our nguillatunes, they go to our activities, they wave our flag. It’s a good thing… because we can cooperate with our ancestral knowledge, central to Chilean society, to fill that lost void.

“Chileans today seek to reconstitute themselves as a community, because Chilean society has rotted at its foundations by applying a neoliberal, individualist, utilitarian, mercantilist model. And what Mapuche society has is precisely the idea of community.”

Previous page Next page