By Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez

Production by Kayla Mi-Kyung Vandervort

with special assistance from Dr. Raymi Chiliquinga

Like many in the Indigenous town of Salasaka in the Ecuadorian Andes, Whirak Quamak is a weaver, one who specializes in the elaborate storytelling tapestries that the town has become internationally known for. When he heard the news of the strange new disease, he went to his pedal loom and began to weave.

Headlines told of the virus arriving in Guayaquil, a major port city some five hours to the south, bringing a wave of illness, with hospitals collapsing and people dying in the streets. He worked the loom day and night, telling the story of the pandemic in a wall-length tapestry: a man lying in a woven shroud, red spots representing the virus prominent in his throat. A distraught, weeping man, holding his hands to his head, seemed to let out a collective wail.

This story is a part of “Cosmology and Pandemic: Indigenous Responses to the Current Civilizational Crisis — Episode 2, Legacy of the Andes,” produced by The Esperanza Project with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The One Foundation. Watch the accompanying film, read related stories, download the PDF and explore the entire transmedia series here.

“I was right here when the pandemic arrived in Salasaka,” Whirak recalls with a sad smile, pointing to two pairs of women in traditional dress embracing each other, and above them, a representation of Tata Inti – Father Sun – weeping cascades of orange and red tears.

“At that time there were ten people who had died, just at the moment when I started weaving here,” he gestures. “And the Sun cried for the ten people…. and indicated that this would all pass….that Nature will accompany us.”

It took two months to finish the tapestry, and by the time it was done, in late 2020, fifteen people had died in Salasaka. But what Whirak began to notice was that the people who were dying were those who went to the overburdened and unprepared hospitals in the nearby city of Ambato. Those who stayed home and used the traditional plant medicines recovered, according to Whirak and to the village president, as well.

Tata Inti’s message to Whirak was true; by the end of 2020, the worst of the pandemic had passed in Salasaka, and there were no more deaths. The people returned to their roots, reviving their traditional medicines and their ancient culture, close to the land that sustains them.

Lea esta historia en español — Los Salasaka: Tejiendo Sabiduría, Sanación y Tradición

The origins of the Salasaka people are shrouded in mystery; their roots come from the Aymara of the highlands in what is now Bolivia, where they resisted subjugation under Inca rule. Eventually they were dispossessed of their lands, becoming mitimaes, from the kichwa word “mitmaq,” or “exile,” to describe people forcibly relocated by the Inca empire, according to the official version of the parish of Salasaka.

They migrated from the Lake Titicaca area in a long and tortuous journey through the region that is now Peru, bringing with them their ancient traditions. These proud and resilient people finally settled some 500 years ago in the foothills of the Ecuadorian Andes, under the protection of what was to become their sacred Apu, or guardian mountain, Teligote.

There they have dwelled for half a millennium, coming to be known for their exquisite weavings and for the rich traditions they have preserved over the centuries. The Salasaka still speak runa shimi (or kichwa); they still spin their own thread, make their own instruments, and save their own muyu (native seed).

Not long ago, every child was taught to weave, to play music and to farm the land as a part of their traditional education. The elders and still some of the younger generation still live their lives in tune with the rhythms of nature, interpreting the language of the birds and the skies, the plants and the stars: a constant connection with the Pachamama (Mother Earth) that lets them know when it will rain, when to plant, and when to carry out the rituals of their Salasaka traditions.

They also learn to heal – sophisticated techniques developed over thousands of years using plants, animals and the powerful teachings of their own Andean cosmovision.

Our cosmovivencia was banished by multiple factors, such as the implementation of an educational model focused on anthropocentrism, the insertion of religion and the imposition of dogmas.

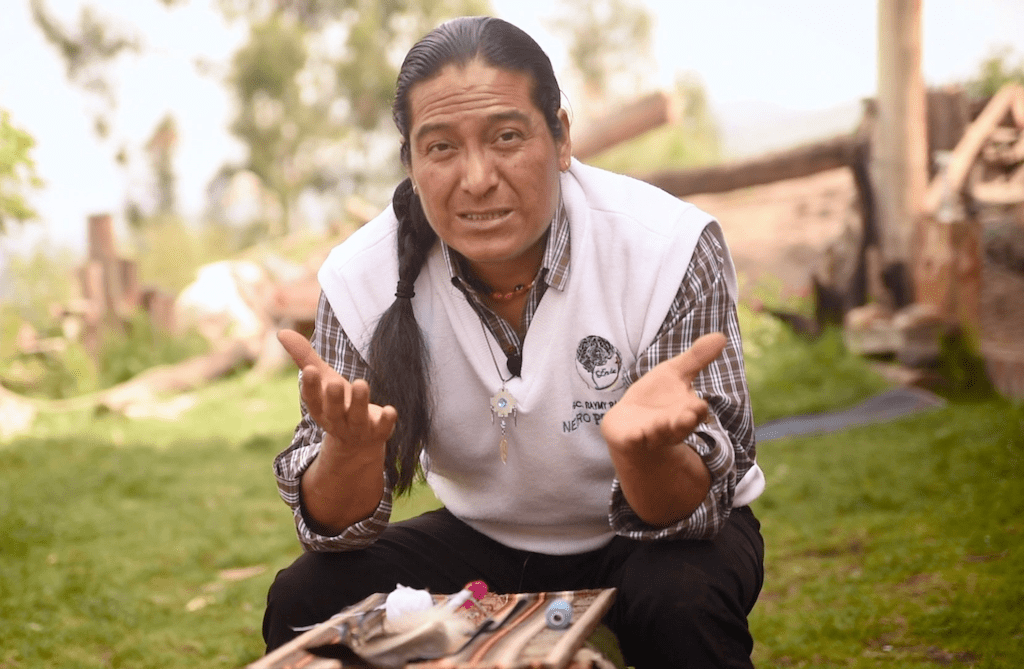

Yachak Dr. Raymy Chiquilinga

Salasaka traditional healer

“All this ancestral knowledge was put to the test when the Covid-19 pandemic arrived,” says Dr. Raymy Chiliquinga, a Yachak or spiritual guide who is also a neuropsychologist, professor at the Amawtay Wasi Intercultural University and Salasaka traditional healer.

“Our cosmovivencia (cosmically connected way of life) was banished by multiple factors, such as the implementation of an educational model that came from Europe, focused on anthropocentrism, the insertion of religion and the imposition of dogmas,” the yachak explains.

In recent times, many had forgotten the traditional recipes and techniques of their ancestral medicine, trusting more in the pharmaceutical remedies widely promoted in modernity. With the health crisis and the lack of responses from the government and the official health system, and with the guidance of experts like Chiliquinga, the Salasaka found in the calamity an opportunity to return to their healing traditions.

The different symptoms of the unknown and contagious disease that threatened the valleys of Teligote were the key to remembering and connecting with the ancient teachings of Mother Nature: fever, sore throat, cough, and exhaustion required a combination of plants from the high-altitude regions and from the tropics, explains the yachak, who has worked with numerous Covid patients, using ancestral medicine to treat the disease.

According to Chiliquinga, COVID-19 is “a form of domination, an invasive life system that colonizes its people.”

“Fear unbalances people, causing them to decline, any viral infection can put them at risk and may even cause them to die,” says Raymy, who identified the town’s few Covid casualties as primarily elders with preexisting conditions. There were no young victims of the virus, according to the yachak and various other sources.

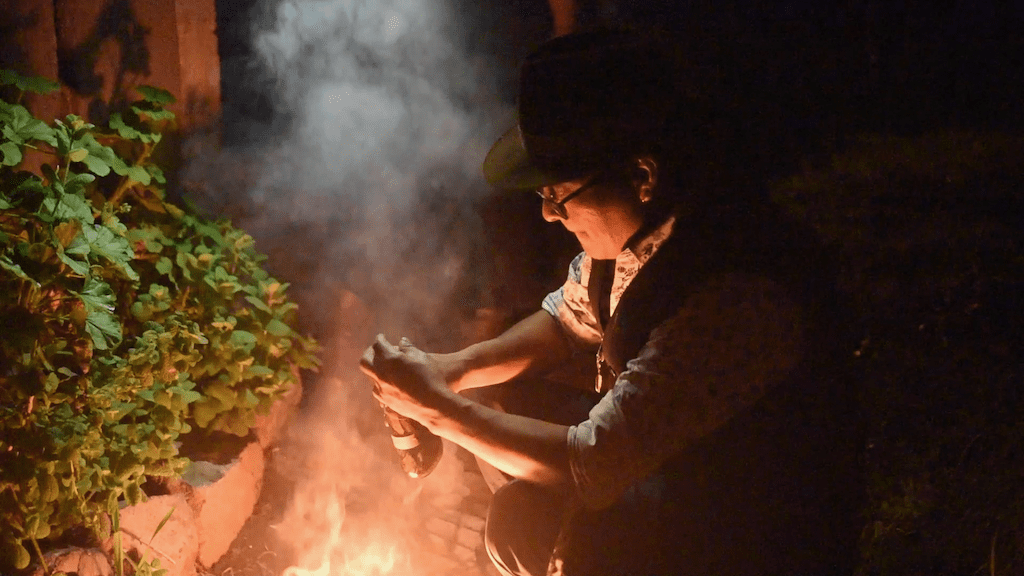

“The ancestral rituals were essential to balance a situation that alarmed the entire community,” he says. The rituals that were practiced the most were “limpias” or spiritual cleansings with the guinea pig, a sacred animal for Andean peoples; payments to the Pachamama with the black guinea pig; preparations or concoctions of bitter and spicy plants, inhalation of vapors and baths with master plants, and even the consumption of microdoses of entheogenic plants.

As with most Indigenous communities in the Andes and throughout the continent, the Salasaka rely on traditional as well as conventional medicine. With the coming of the pandemic, some invoked the curative power of their Apus; climbing up through the forests of Teligote, they gathered the great variety of medicines that grow there, and they prayed. Others turned to medical doctors, in a system that was severely underfunded, with mixed results.

“Like the town of Salasaka itself, all the authorities worldwide were not prepared to face this pandemic,” says Salasaka Parish President Antonia Quinapanta. “As authorities we had to go through many situations, but we did our best to carry the situation forward with strength, giving encouragement to our population. As indigenous people, we have coordinated and we have cured ourselves with our own natural medicines from our locality.”

Unfortunately, they didn’t get the support they had hoped for from the Ministry of Health, she affirms. The community’s small clinic had a meager medicine supply, and no Covid tests or protective gear for the health personnel.

“We negotiated with some universities, with indigenous organizations, and that is how we have been able to manage. We continue to fight as we always have with the natural medicines to get through this.”

Among the many plants used in Salasaka, those cited by the people interviewed include quina or cascarilla (Cinchona pubescens, used to make quinine); Juanilama (lippia alba), in the verbena family; a plant called iza, with antiviral properties; white willow, a powerful anti-inflammatory and pain reliever; elderberry, for respiratory problems and fever; ginger, and of course eucalyptus, which, though not a native plant, has turned out to be one of the most powerful covid treatments of all.

When we reached out to her in March 2023 for a follow-up interview, Quinapanta confirmed that the 15 people from Salasaka who died of the virus were all hospitalized in Ambato. Those who stayed home were able to recover.

That’s half the number that the hospitals reported to the government, however – in a trend that was observed elsewhere, the hospitals reported all the deaths as Covid-related. Later when the local authorities reviewed all of the death certificates, they found that half the deaths were unrelated to Covid – and though they reported that information to the Ministry of Health, the official figures for Salasaka never changed.

According to Quinapanta, that first year of the pandemic about 150 families tested positive, and 600 families went into isolation as a preventive measure. Many people contracted the illness, but after the first year, there were no more deaths, she emphasized.

We saw the importance of our native plants here, in our locality, and in this way we got out of this crisis that affected us worldwide

Antonia Quinapanta

Salasaka Parish President

The pandemic had the positive effect of helping people to remember and revalue their traditional medicines, she confirmed. “We saw the importance of our native plants here, in our locality, and in this way we got out of this crisis that affected us worldwide,” she said.

What was more, when eucalyptus was identified as a powerful medicine for treatment of Covid symptoms, the community sent truckloads down to communities on the coast. “We were in solidarity with the coastal region, since they also needed to be cured, and we helped them,” she recalled.

For the Salasaka, as with most Andean peoples, recovering their plant medicines has been an important component of facing the disease. But facing down Covid has had less to do with the physical dimension, they say, than the psychospiritual one.

“For us, the virus is a microcosm of how we begin to disintegrate, and we start from understanding fear. Fear is the thing that unbalances and makes us easy prey, not only for Covid, but for different types of diseases as well,” says Chiliquinga, who has spent his career delving into the matter.

“And the other point in this part is to understand that death is part of life and with Covid, you have to be prepared to die. And death is good, death is positive. But when is it positive? When all your states of life, when all your relationships, the balances of life, you have it harmonized.”

Understanding psychology from the West is mainly to understand the various mental processes as explained by the fathers of modern psychology such as Sigmund Freud, B.F. Skinner, and Ivan Pavlov, says Chiliquinga, founder of the INKARTE–YACHAY Center of Ancestral and Neuropsychological Medicine in Salasaka. But then he came to see that understanding the human being is not just a mental question.

“From the Andean cosmic vision, it is understanding the human being from the five bodies: the mental body, the physical body, the spiritual body, the emotional body and the energetic body. That is when the human being has the power to enter the healing process.”

Fear is the thing that unbalances and makes us easy prey, not only for Covid, but for different types of diseases.

Yachak Dr. Raymy Chiquilinga

Salasaka traditional healer

An imbalance in any of these five bodies can leave the body vulnerable to any kind of illness. So healing work must happen on all of those levels, he explains. “These five bodies are responsible for balancing your states of life while at the same time understanding and accepting that death is a part of life,” he said.

As he speaks, Raymy prepares condor feathers for a healing ceremony for a Covid patient. The feathers are used to cleanse the aura, he explains, which was the first step in the treatment of Covid patients, who generally arrived with an impaired mental state.

“In this time of change, Mother Nature has given us many messages and has also given us many tools to protect ourselves,” explains the yachak. One of those tools is the condor feather, which Raymy is guided to find through his dreams, and are fundamental to the Andes cosmovision.

“The condor – mallku kuntur – for us is the bird of Hanan Pacha (the world above), of the psychic spheres. The condor is wisdom, it is tranquility, it is purity, it is strength. So the breeze, the aura of the patpa, the condor feather, cleanses that fear, and the air enters the bloodstream through the nose, and it strengthens the thymus. And it is that which produces lymphocytes and which allows the immune system to be enhanced.

“So in this time of change, of Pachakuti as we call it, people especially need the wise men and women to have instruments, cosmic tools, to do their work.”

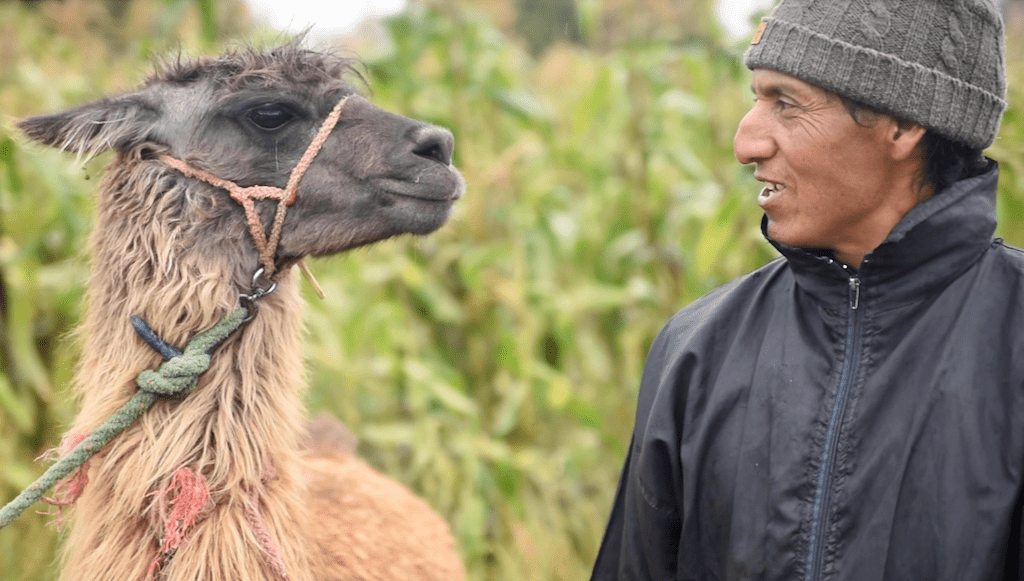

Alonso Pilla, like most of his contemporaries, is a traditional weaver, a musician and a farmer, as well as the owner of a hostel, Runa Huasi, where these days he shares his culture with visitors from around the world.

For Alonso, too, health is a question of attitude, as much as anything. He clearly recalls the fear of the first months. “Everyone told us that with this pandemic, we are going to die.”

He found himself thinking a lot about his parents’ generation. “In those days there were our taitas, our wise men, our ancestors…They were very strong, they were true healers, they knew how to prepare the herb, they knew how to prepare the energetic pulse that is spirituality,” he recalls. “If (Covid-19) had arrived at that time, our taitas calmly would have fought this type of disease. They weren’t afraid of anything, nothing at all.”

When he first heard the news of the Covid-19 pandemic, at first he didn’t imagine it would arrive in Salasaka; illness there is rare, since the people live an active life, working the land, eating their own homegrown quinoa, beans and vegetables.

It was hard in the beginning to find traditional medicines, he says; people had begun to forget about the old ways. But with time, they realized that connection was still there. Little by little, speaking with the elders and through their own intuition, they began to remember.

We were very individualized, each one for themselves. But the pandemic came and we got very close. We looked for communication, we looked for connection, everywhere.

Alonso Pilla

Salasaka artist and bussiness owner

“We are no longer afraid here, and the people are well prepared, since we already know what this type of situation is,” he says firmly. “Here we have our own energy, our own power and our own mentality. It is our Apus, our taitas, they are protecting us, protecting Salasaka.

“When the pandemic came, we were there once again, doing energetic spiritual medicine.” For him, as for many who follow the culture, the health-illness dichotomy is a question of mind over matter. “When thinking psychologically, mentally, energetically…. If you don’t think much about the disease, you can live calm and healthy…Mental power. But If you think, oh, this illness, and this, that and the other, then the illness will continue; it will affect the person because he no longer has energy, he is weakening himself.”

In these times it is fundamental to maintain a positive attitude, Alonso maintains. It’s helpful to live in the country, breathing fresh air, drinking pure water from the mountain springs, eating homegrown food and living an active productive life – especially by working the land.

“You have to transmit, you have to spread the word, you have to give this energy. ‘Look, sister, look, nephew, look, cousin, look, uncle, don’t worry. Grab a hoe, a machete, a shovel.’ Here we work the land. When an indigenous person works energetically, then we don’t have any type of virus.”

His wife, Juliana, is a case in point. She became infected and fought the disease with traditional medicine and a positive attitude – and she kept on working.

“It did catch me, but I healed with medicinal waters from right here, with the plants that I prepared with them,” said Juliana, who wears her own handwoven clothing and spins fine merino wool into thread as she speaks, as is the custom and one of her daily chores. “I did go to a doctor. But no, the doctor did nothing for me. I didn’t heal. They injected me with everything, but nothing happened to me. I myself had to be very strong to stop this disease.”

She made hot baths of eucalyptus and cypress and inhaled the vapor, and she drank large quantities of herbal teas. “Then I went out and took care of the animals, the pigs and everything.”

It felt a bit like having the flu, she says. “I felt bad, just a little bit, no more than three days.”

She also takes a teaspoon every now and then, or when she starts to feel symptoms coming on, of a medicine known locally as cascarilla — the antimalarial quina tree, used to make quinine, and which has shown positive results in medical studies in the treatment of Covid symptoms. “I have a teaspoon at breakfast, and a teaspoon before I go to bed. With that, I’m fine.”

Her parents, 83 and 80, passed through the pandemic more easily than she did; in our last conversation in March of 2023, they had not caught the virus. “I think my parents are a little stronger because they eat quinoa, they eat barley rice, they make morochos, coladas (native corn preparations), they eat cabbage… all of that protected them. Food is fundamental. Actually, we eat a little food with chemicals…That’s why I think the disease catches us faster. We are weak, but no, my parents are not.”

One of the benefits of the pandemic, says Alonso, was that neighbors who barely had time to speak began to seek each other out and communicate. “That was very important in those days, spreading the word. Because one neighbor would come with one plant, and another would choose a different plant… we all learned from each other, and we supported each other, as well.”

At the onset of the pandemic, like many Andean people, Raymy sought the wisdom of Mama Coca, the sacred leaf of the coca plant. What he saw was that the pandemic has revealed a humanity that has not yet been “humanized” – a species that seeks to dominate others, and the Earth, in exchange for material benefit – and that some were using the virus itself to those ends, profiting from it and using it to control the masses.

Under the Western economic system, says Raymy, the Andean ideal of sumak kawsay, or buen vivir, the good life, has been distorted from a model of balanced, ecological living to a never-ending quest for material goods. This has led to a devastating destruction of the environment that has much to do with creating the conditions for the pandemic.

“Deforestation is the Sacha yurakuna wañuy; it is the annihilation of the beings of the Kaypacha, the visible world, which are the yurakuna, the plants. For us, to talk about annihilation is to feel pain; everything we do or talk about is created by plants, everything.

“But the economically powerful says: I need that economy. Why? Because sumak kawsay for them is to have a car, have titles, have brand-name clothing, have trips to other countries. On the other side he says, no, finally, I have Sumaq Kawsay, but in exchange for what? In exchange for sacha wañuy, which is deforestation, the annihilation of the plant world.”

That process is going on all around them, with the rapid growth of the nearby city of Ambato and the increasing urbanization of Salasaka. In the context of the pandemic, this has grave implications, he says. “Why? While there is Mother Nature we can talk about ancestral medicine. As long as there is no Mother Nature, one cannot speak of ancestral medicine…. Mama Coca says this is a beginning, many things will appear, other pandemics will appear, and there will be weakness.”

But in Salasaka, the people and the land are holding strong. The pandemic awakened new interest in the traditional ways of life, and strengthened the bonds in the community as well. “Before this pandemic we were very individualized, each one for himself,” said Alonso. “But the pandemic came and we got very close. We looked for communication, we looked for connection, everywhere.”

Raymy, Alonso, Whirak and others make their treks up Teligote, like their ancestors before them, to find their medicine, their Apu, and their own inner wisdom.

Up on Teligote, with its remnants of cloud forest where the trees are draped with ferns and mosses, the waters run clear and the winds blow fresh and clean. This is where they find the bamboo for their Andean flutes and the wood for their drums, the dyes for the fabrics they weave — and still, to this day, the treasure of natural healing.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

Previous page Next page