“But since people who are harmed deeply yearn for truth and justice, addressing this is essential for reconciliation.” — Ervin Staub Ph.D., Nazi holocaust survivor, advisor to the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, Rwanda, 1999.

Oglala Lakota citizen Maria Hazel Stands takes the microphone. Surrounded by Pine Ridge Indian Reservation community members she accepts the introduction as a “survivor” of Red Cloud Indian School, where they are gathered under a canopy of trees in the grassy yard.

“I went to school here back in ’68-’69. I remember I tried to speak my language. I said ‘lowáčhiŋ.’ That means ‘I’m hungry,’ and a nun heard me. They said, ‘We don’t want ever, ever to hear you speak your language.’ You see that steeple. They put me up there. They said, ‘You’re gonna live here. You’re a monster. You’re a little monster for speaking your language. We don’t want that here,’ and I was up there almost a week.”

Para leer este artículo en Español, da click AQUÍ

Stands is one of several speakers invited by the Oglala Lakota Chapter of the International Indigenous Youth Council to speak at an October presentation of demands to the administration of the Jesuit-run former Indian residential school.

The #childrenback event presaged Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s announcement Nov. 16 of her decision to lead Republican Party support for federal legislation to redress Indian boarding school atrocities dating back to the 1880s across Turtle Island.

The youth council’s redress demands range from the Catholic Church’s repeal of the Vatican’s 1493 papal bull, known as the “Doctrine of Discovery”, to the release of archival records, to the immediate deployment of ground-penetrating radar in search of children’s unmarked graves from the early days. Back then, the institution bore the name of Holy Rosary Mission.

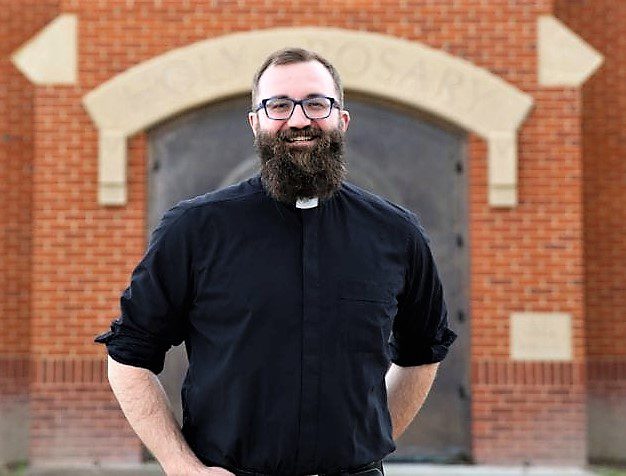

School President Raymond Nadolny, Ph.D., stood with other administrators, telling the youth, “It is with a sorrowful and grateful heart that we welcome you…and we are here to listen.”

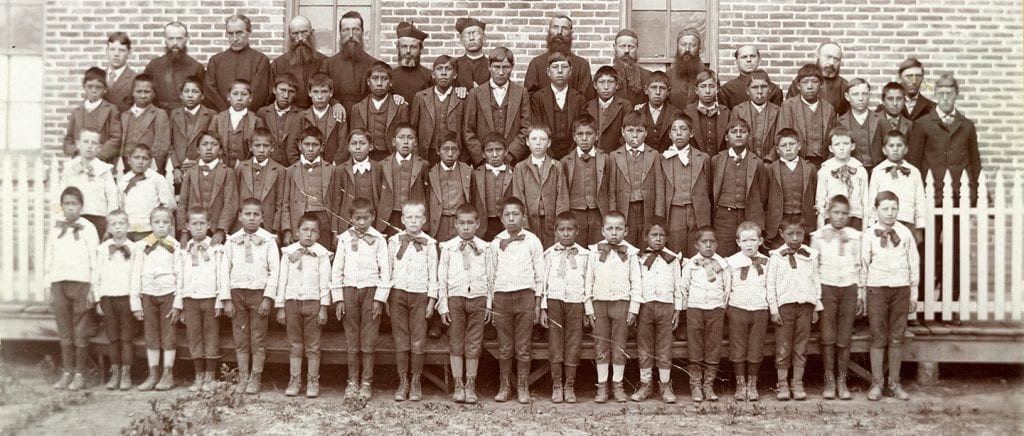

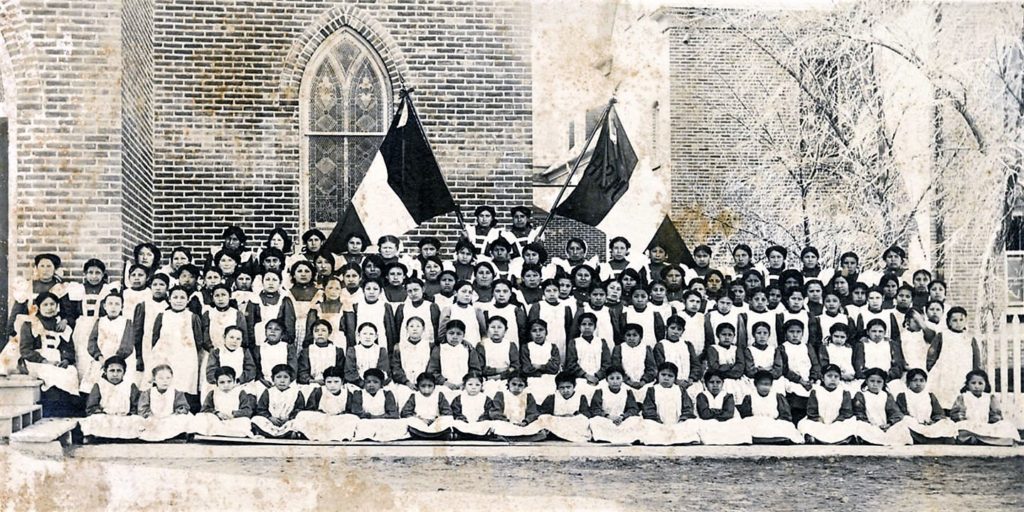

Deborah Parker, Tulalip-Yaqui-Apache director of Policy and Advocacy at the national non-profit Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, NABSHC, helped the youth organizers arrange the face-to-face encounter. Beginning in the 19th Century, the U.S. government funded 12 Christian denominations to operate nearly 500 residential schools in 30 states. They followed a policy on children that Cavalry Capt. Richard Henry Pratt espoused from the opening of the first one in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879: “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.” Red Cloud Indian School is among 64 boarding schools that remain open today in Alaska, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. All of them have cemeteries.

Nadolny created a Truth and Healing Commission to address this history at Red Cloud Indian School shortly after he became president in 2019. He is the first non-Jesuit in the position. Commission members sought guidance from the NABSCHC, while facing off with the Covid-19 pandemic protocols. When ground-penetrating radar revealed 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada, they were among the officials who felt spurred to action.

“When I imagine the 215 Indigenous children at Kamloops who were secretly buried so that no one would find them, I am sickened at how much fear they must have experienced during their short lives,” Red Cloud Indian School Executive Vice President Tashina Banks Rama wrote in an op-ed in June 2021. The daughter of American Indian Movement founder Dennis James Banks, she recalls the “horrific” story of her father and his siblings being wrenched away from their homes to attend boarding school in Minnesota.

“My personal struggle today is that Red Cloud Indian School, where my children thrive as students, where their brown skin is celebrated and their long hair respected, and where I serve as a leader, was once a boarding school,” she said.

After 130 years of evolution, “the school is transforming itself into an Indigenous-led, community-focused and spiritually based organization that serves our Lakota relatives. Red Cloud is also finally confronting its dark history—and acknowledging the complicity of the Catholic Church in that history,“ she said. The commission “signals our commitment to acknowledging and examining the trauma that is part of our history as an Indian boarding school.” She noted the commission was considering deployment of ground-penetrating radar, “if our Lakota community wants that.”

Four months later, the youth and invited elders called for a little more action. Speaking at the assembly on the campus just outside of the Oglala Sioux Tribal Headquarters of Pine Ridge Village, South Dakota, former Tribal Chair Bryan Brewer, who attended the school, said, “There were many good things that happened here. It provided good education for us. But there were many bad things. After what happened in Canada, I am very concerned that might have happened right here. I don’t know why we are not going over the grounds right now with the radar. If I was the (school) president, that is the first thing I would have done.”

Brewer, whose grandfather and father attended Holy Rosary, said his dad didn’t want him to. “He said, ‘They’re mean.’ But because all of my friends went to school here, I wanted to go to school here. There was a lot of abuse. There were beatings every night.”

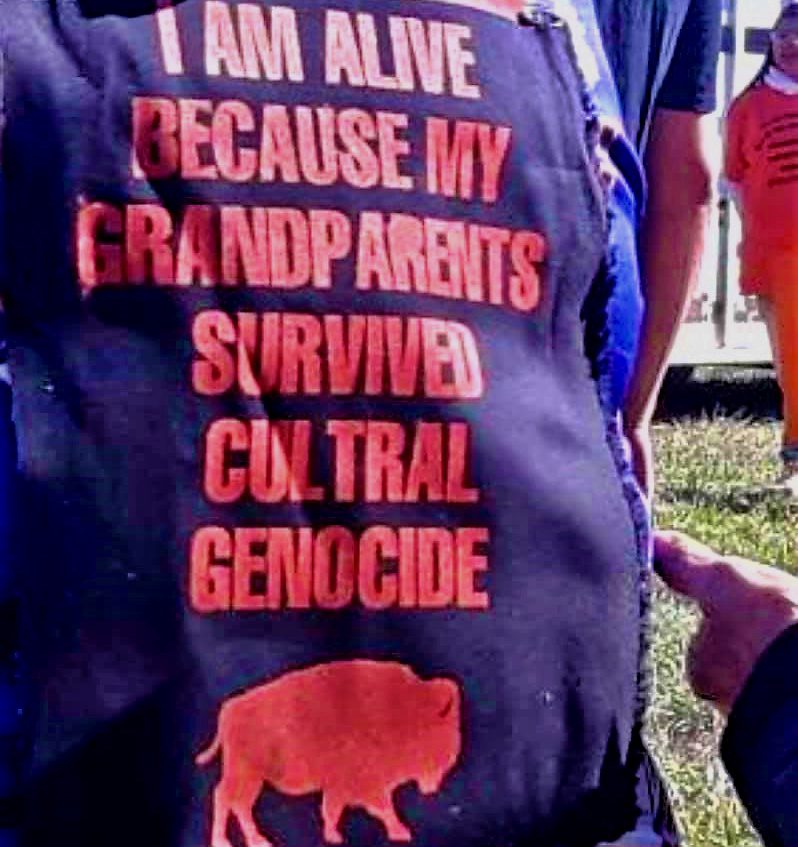

The legacy is a situation in which today’s adults carry on the violent behavior they learned while institutionalized, he noted. “I’m concerned about how those of us who went to school here were affected. We know that when we are abused, we can grow up to become the abuser. Right now, our children go to school every day abused mentally, physically, sexually, and we wonder why our children cannot learn.”

He received traditional cheers of ululation when he said, “I want to thank the administration for being here and we don’t need an apology from you. We need an apology from the Vatican for all of our people on all of our reservations. This happened all over the United States and in Canada.” He praised the youth for standing up for the cause and organizing the event.

Another Holy Rosary survivor, Alex White Plume, who took part in the first revisions of the program half a century ago, called for a change of the school’s sports team name.

“Let’s not mistreat these priests or the nuns,” he entreated. “Maybe they will be honest and share our feelings; and I wish they would change that name Crusaders.” Flanking him were youth with posters reading, “Red Cloud was not a Crusader” and “Search the Church.”

Photo by Candi Brings Plenty

“Since first contact with the Catholic Church, all they’ve been doing is crusading, trying to turn us into white people. Mitakuyape (my relatives), we are a poor imitation of white people,” continued White Plume. “We have abilities, a different language. We have ceremonial ways that are really beautiful that help us with our historical grief and trauma that was caused by this black robe that came amongst us.”

White Plume met with a representative of the Holy See (Roman Catholic Church governing board) in the United Nations offices in New York City at the request of the late Chief Oliver Red Cloud to demand revocation of the “Doctrine of Discovery.” It was to no avail. Holding up a copy of the papal decree, he said, “This document is still in effect; they still use this. This is the document that gave Columbus the right to kill us and get us out of the way. It said that they could own the land.

“So that’s responsible for over 90 million people being wiped out on our lands here. That’s a reason for our historical grief and trauma. We need to get it out of our DNA. We need to get it out of our blood to be Lakota again.”

He called on the school’s new administrators to help deliver the message to the Pope. Sicangu Lakota citizen Cheryl Angel then stepped up and joined him in torching the replica – to the sound of more jubilation.

Angel, a third-generation boarding school survivor, told The Esperanza Project, “I’d like to see a new papal bull.” It would admit the Church’s fault in the historic trauma that boarding schools caused, return the lands occupied by missions worldwide, and fund reparations supporting local community initiatives to reestablish the “societies of peace” that existed pre-contact.

“A religious organization used its authority to abuse an entire race of people. Indigenous children were treated as sacred until they met Christians. All they ever knew was peace and love. Then they were treated like dirt. They had no right; I don’t care what color you are.

“How do we make that point? I’m looking for someone to be criminalized,” she added. “Turning over all the old boarding school records to each tribe would be a good start, and if there’s some of the perpetrators alive, make them accountable. There’s so much space for accountability, so much room for healing.”

By October, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission acknowledged findings of more than 6,000 unmarked graves. It had previously documented 3,200 children who died while at residential schools but suspected the number of deaths could be much higher. The commission has released the names of 2,800 children who could be identified; in many cases family members had never been notified about their deaths.

Rwanda’s National Unity and Reconciliation Commission addressed some 750,000 deaths in eastern Africa’s 1994 post-colonial genocide. Through neighborhood tribunals, survivors could obtain investigations of specific cases, penalties, and reparations. The accountability and healing process led to legislation instituting free elementary education and banning discrimination in government hiring.

However, Red Cloud Truth and Healing Commission Executive Director Maka Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux citizen, commented, “The term reconciliation doesn’t always work very well in Indigenous communities,” he said. “Reconciling means returning to some kind of positive relationship, but there is no returning here. It always started from this place of imbalance. We are responsible as the perpetrator institution to provide a platform for survivors’ stories to be told and … to tell the truth as we know it.”

Commission member Brad Held, pastor of the Pine Ridge Catholic congregation, recognized healing can’t occur before confrontation with the truth about the historical impact upon community and family life, child rearing, and the connection of trauma to addictions. A Jesuit team in the U.S. capital is lobbying in favor of a law to support that, he revealed. “Red Cloud Indian School Board of Directors approved our support of legislation,” he announced.

SB 2907, the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act, would establish a tribunal to investigate and document United States Indian boarding school issues, locate the graves of Native children who died while attending these schools, and provide recommendations to Congress.

“For many years, thousands of Native children were taken from their families, homes, and communities, and forced to attend boarding schools far away,” Murkowski recognized in co-sponsoring the bill. “These Indian boarding schools stripped Native children of their identities and forced them to assimilate and conform to an identity that was thought to be more acceptable to Western society. Many Native children were abused, both physically and emotionally. Many developed illnesses and died — and were buried far from home. In many cases, their families and tribes were never notified of their death.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) is the lead sponsor of the proposal after she and former Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) first introduced it. With Haaland since tapped to head the U.S. Interior Department, Representatives Sharice Davids (D-Kansas) and Tom Cole (R-Oklahoma,) have reintroduced a House companion bill, HR 5444, of which Congressman Don Young (R-Alaska) is also a cosponsor.

Held said one of his fondest hopes is that the law will pass. “We’re going to be uncomfortable for a while, and that’s what this is all about: not just a transformation for the Indigenous community but healing for all of us.”

Angel stressed that the intergenerational trauma resulting from the boarding school era claws into every corner of life, as youth seeking solace fall victim to predators of any stripe. “I would like Congress to say, ‘Indigenous people are endangered; they’re targets.’ People literally are hunting us. Our young girls are prey to drugging, violence, human trafficking, murder, and disappearance.”

A law that tips the scales toward justice could underpin Native efforts to recover cultural strength once it unveils the truth and helps “name the abusers,” she said. “You can’t just point the finger at someone. it’s not just one-sided. We as community have a lot of work to do; we have to be responsible for healing. But we can’t have that unless we hear who says what they did wrong.”

- Clemency for Lakota icon Leonard Peltier called ‘moral indictment’ - January 21, 2025

- Lakota tribes, grassroots close ranks to defend Black Hills watersheds - January 21, 2024

- Native ‘hempsters’ follow global cooperative example - August 30, 2023

Indian Boarding Schools Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation Red Cloud Indian School.

Thank you Talli for this important article.

Please feel free to share it!