The drum’s deep heartbeat reverberated through the clearing, steady as the women swayed in flowing white garments beneath the waning moon. From the slopes of Cerro Gordo, the pyramids of Teotihuacán could be glimpsed faintly in the haze below, reminders of another era of ceremony and community. Voices rose from the Casa de Cantos: “Hey, hey, hey, Ometeotl… Tlazocomati, tlazo, tlazocomati.”

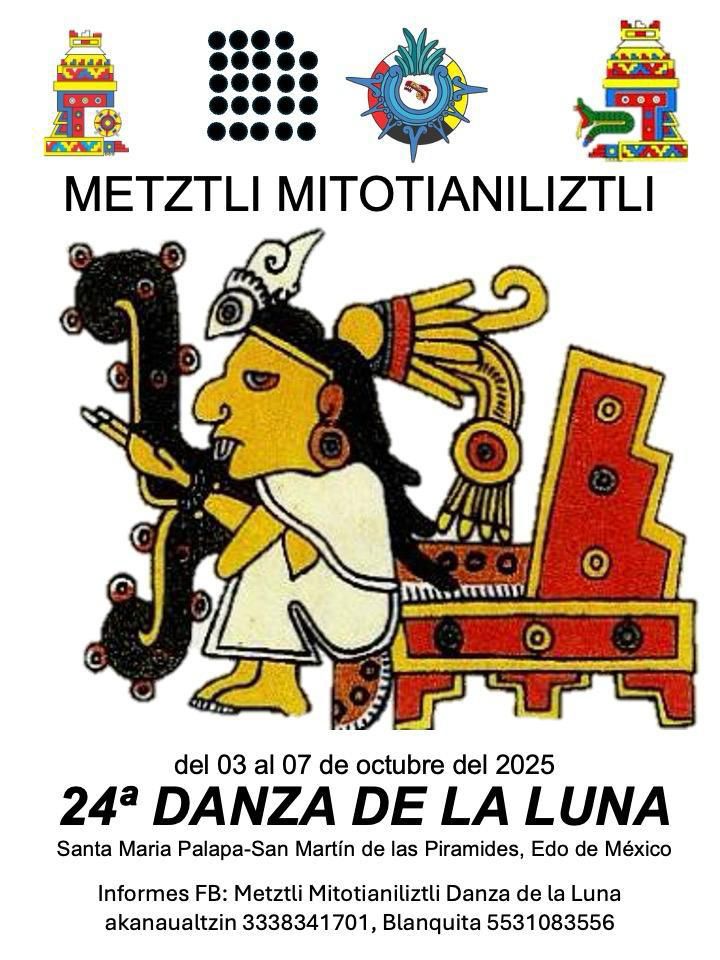

It is called the Danza de la Luna, the Moon Dance. For four nights each year, women gather here to move in rhythm through the darkness, to fast, to sing, to tend the fire, and to carry forward a tradition revived in Mexico more than three decades ago.

Overseeing it all is a woman whose path began in science but took an unexpected turn toward ceremony: Abuela Ana Lucía Chinas, who has guided the Moon Dance circle at Cerro Gordo for the past 18 years.

See the first part of this series, an interview with Abuela Ana Lucía, HERE.

Lea esta historia en español AQUI.

The ceremony and the place

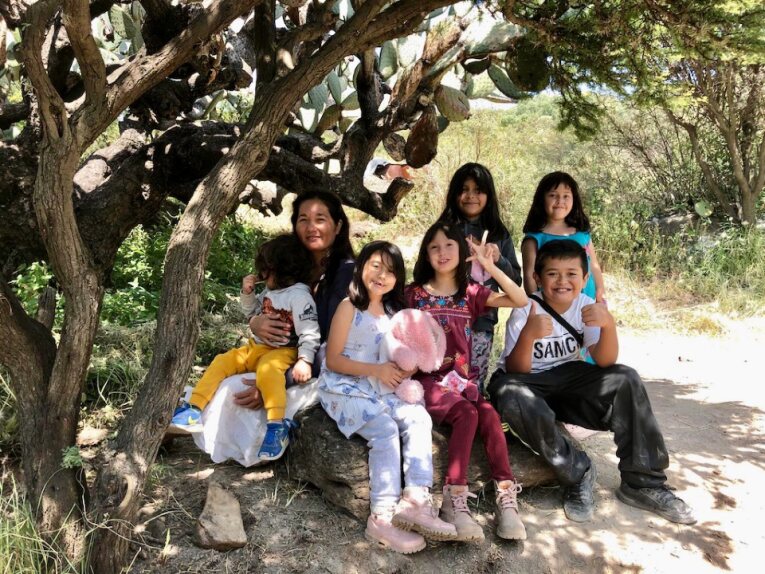

By day, Cerro Gordo is alive with preparation. Tents sprout across the campground; children dart among nopales heavy with red fruit; smoke curls from kitchen fires tended by volunteers. Support teams collect firewood and fetch water. Women gather tobacco ties—rezos—each one wrapped with a prayer and tied to string that drapes over the central nopal cactus.

At night, the work becomes ceremonial. The dancers move in rhythm, the singers beat the huge huehue drum, the Fire Eagles tend the flames that heat the temazcal stones. Roles are clearly defined: danzantes, singers, firekeepers, cooks, support people.

Participation is not casual. Women prepare all year for these four nights, often dedicating months of service before being allowed to enter the circle. Contributions are made in offerings, in labor, and in discipline.

As Abuela Ana Lucía explains:

“The dance prepares us—it forces us to face sleep, fear, and the cold. You can’t climb the mountain and come back unchanged.”

The dance, she says, is meant to transform.

From engineer to abuela

Ana Lucía was not always a ceremonial leader. In 1992, she was a 22-year-old chemical engineering student at the University of Guadalajara. That year, Indigenous runners from the Peace and Dignity Journeys arrived in her neighborhood. Their philosophy and presence struck her deeply.

Two years later, pregnant with her daughter, she made a decision that would change her life.

“I felt I had to leave my child a better world. That’s when I began to dance—while still carrying her. Over time I realized it wasn’t just the dance itself, but a whole set of practices surrounding it.”

Her early path included the Danza del Sol, whose origins are often attributed to Lakota traditions. But Mexican ceremonial leader Tlakaélel taught that the Sun Dance resonated with ancient practices in Mexico as well. Out of this dialogue grew the vision of a women’s ceremony.

“Along the path of Nahui Mitl (Four Arrows, symbol of the four sacred directions), the partner of Tlacaélel, Totlalnantzin—Patricia Guerra—began to ask: what is there for women? The Moon Dance, it’s said, came to her in a vision, which she then enriched with what she had learned and shared with women of many different nations.”

The first Danza de la Luna was held in 1992. A decade later, Ana Lucía was asked to step forward as guide. At first, she resisted.

“At first, when they asked me to lead the dance, I said no… Later I accepted, and by my fourth year I was already recognized as a grandmother of the Moon Dance—and I stayed. This is now my 22nd consecutive dance; I haven’t missed a single year.”

While my circle, Kalpulli Koakalko, is now led by Abuela Ana Lucía, it is not the only Danza de la Luna. Another widely known circle is led by Abuela Tonalmitl (Guadalupe Retíz), whose Moondance Xochimetztli is regarded by many as a mother circle drawing participants from across Mexico and internationally.

Challenges and resilience

Her path was not simple. She lived in Jalisco, hundreds of kilometers away, with limited vacation time. She was a single mother and worked in her profession as an engineer.

“At first it felt impossible: I was living in Jalisco, had very little vacation time, was a single mother and working in my profession. Many times I thought I wouldn’t be able to keep it up—but every year I came back. What sustained me was the conviction that this path was for my daughter and for the women who would come after me.”

The community itself faced difficulties. Councils were formed and fell apart. Different groups clashed. Yet year after year, Ana Lucía continued, leading the women through the discipline of the dance.

Her style, she acknowledges, is demanding.

“I’ve always been very disciplined, very strict about schedules. When I began to learn about Mexicanidad, I realized that the values of our ancestors still endure. And I saw that it’s not just about science—there are other things the eyes can’t see. What I wanted was to leave my daughter another kind of world: one not based only on competition, money, and business.”

A discipline against quick consumption

The Moon Dance is not designed for everyone. It requires long-term commitment—often years of service before a woman is admitted as a dancer.

“We are disciplined: we ask for at least a year of service and preparation. Not everyone wants that in today’s fast-consumption society.”

She contrasts this with offerings of “spiritual tourism” or short weekend ceremonies. The Moon Dance demands endurance: fasting, cold nights, year-round preparation, and the will to continue.

“When I’m in the circle, no one lifts my feet for me. I’m the one who has to do it.”

This insistence on personal responsibility, she believes, is what gives the ceremony its power.

Transformations

Over the years, she has seen women’s lives reshaped by the discipline of the dance.

One mother, locked in a custody battle after her partner took her daughter away, told her: “If I hadn’t had this network of women, I wouldn’t have made it through.”

Another participant, an academic researcher, shifted her studies to include a gender perspective. Others, who once thought they would never become mothers, decided to start families after experiencing the dance.

Abuela also points to generational impact: women raising sons with respect for women, shaped by the values of the dance.

“That gives us an incredible strength of will… it helps us recognize when a path is not ours.”

These changes, she says, are proof that the dance is not just symbolic. It alters the way women live their lives after they descend the mountain.

Continuity and the future

The Moon Dance at Cerro Gordo has now persisted for more than three decades. Even in the pandemic year, women found ways to continue. Leadership has become intergenerational: her daughter Ketzalmetztli now leads the traditional songs, gathering women each week around the drum.

“It began in the 1990s, before many of today’s frameworks around ‘the feminine.’ The dance teaches us about duality, about complementarity. In tradition there are roles, and those roles are respected; but if someone is missing, we step in and take on those functions, and the prayer continues.”

For Ana Lucía, the future lies in forming new guides.

“We are forming guides—leaders who are conscious and well-prepared.”

Dawn and legacy

By the time dawn breaks, the women have completed four rounds of dance and song, each lasting an hour or more. Exhaustion shows on their faces, but the rhythm never falters. One by one, they move toward the North gate of the circle, making a final spin before stepping out into the morning light.

The pyramids emerge from the haze below, bathed in early sun. Children laugh as they chase each other among the tents. Women gather in the kitchen to prepare food.

For Abuela Ana Lucía, the true measure of the dance is not in what happens on the mountain, but afterward.

“They need to be who they are, to learn their own nature… no one is going to do that for them. They can, they know how.”

And with that, the women disperse back to their homes and communities—carrying with them discipline, community, and the memory of the moonlit circle.

What to know if you’re invited to support

- The Moon Dance is not a public performance; attendance is by invitation.

- Roles include dancers, singers, firekeepers, copaleras (women tending the sacred copal incense), kitchen crews, and support people.

- Contributions are made as offerings of work, food, and resources.

- Dancers fast during the four nights; support people may eat lightly.

- Respect for protocol is central: no photos during ceremony.

Glossary

- Temazcal: sweat-lodge purification.

- Huehue: large ceremonial drum.

- Rezos: prayer ties made of tobacco and cloth.

- Nahui Mitl (Cuatro Flechas): symbol of the four sacred directions.

- Kalpulli: community or ceremonial group.

In another life, Tracy Barnett is Macuilxochitl, or Five Flower, and a Water Carrier. She has danced for 8 years with the Kapulli Kuetzpalkalli dance circle in Guadalajara under the guidance of Abuela Ana Lucia Chinas.

For more information, follow the group’s Facebook page.

For a deeper dive, you can read the full interview with Abuela Ana Lucía Chinas in The Esperanza Project; and also Moon Dance: Living Ancient Mysteries, Healing the Mother Wound, Tracy’s first-person account of her first Moon Dance in October 2024.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026