Fishermen of southern Sinaloa and the migratory birds of North America have something in common: they suffer the impacts of environmental degradation of the Huizache Caimanero lagoon system, one of the most productive along the Mexican Pacific coast. The pangas (open fishing boats) that used to return loaded with shrimp have been left empty, and birds that fly thousands of kilometers each year from Alaska, Canada and the United States to spend the winter in this place have lost habitat for resting and feeding.

The drop in fishing production, on which some 4,000 families depend, is a symptom of a larger problem. The lagoon, located between the municipalities of Mazatlan and Rosario, is losing depth. It is drying up and in 15 years could disappear if it is not restored.

Para leer este artículo en Español haz click AQUÍ

The Huizache Caimanero was designated a Ramsar site in 2007 due to its importance for migratory birds in Mexico. In its registration form it is mentioned that this coastal lagoon became the most productive along the Mexican Pacific, with daily catches of 5.3 tons of shrimp and a historical record of 32 tons in a single day in 1983.

The document indicates that from 1990 to 1994 an average of 1,060 tons of shrimp per year was fished, but in the following six years production was reduced by a third, due to environmental deterioration, so that between 2000 and 2004 the average catches were just 389 tons per year.

Now, there are no good seasons, only bad and medium ones, the fishermen attest. In the best of cases, the catches made by the 26 fishing cooperatives in the area reach 200 tons; but if things go wrong, the shrimp will be so scarce that fishermen won’t be able to recover what they invested in gasoline and in repairing their boats. In these circumstances, there are those who prefer not to venture out to cast their nets.

“We haven’t fished for two or three years,” says Ramón Rojas Quintero, president of the Potrerillos cooperative. On top of a panga, with a wooden handle, the fisherman measures the depth in the center of the lagoon, which, after the first summer rains, is less than one meter.

On the horizon, you see water bordered by hills and crops. Like a mirror, the clouds are reflected on the surface of the lagoon, which only changes with the passage of the boat motor. From his perspective, Gilberto Palafox Uzeta, president of the Federation of Fishing Cooperatives “United for the Caimanero Lagoon”, agrees with Rojas Quintero. He notes that in the good times the cooperatives were prosperous, but now the fishermen must seek employment elsewhere because the activity is no longer profitable.

“Before, it was not like that. On the contrary, the cooperatives helped the communities and the schools, because there was a lot of product, a lot of resources. There were exports,” recalls Palafox.

On the way to the pier of the Mataderos Cooperative, a group of men are seated near a row of beached pangas. Amid a full ban on shrimping, fin fishing is also rare, as is work in general. The busiest mend nets, with the help of women.

Another Thing in Common

Fishermen and their families are not the only ones to suffer from the low productivity: but also migratory birds that will begin to arrive in August; and a great diversity of fish, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates that are less visible.

Migratory birds, however, are considered especially vulnerable because they breed, overwinter, and visit sites that have been drastically altered globally over the last century. This is outlined in the Pacific Shorebird Conservation Initiative prepared by various international organizations.

The Initiative highlights that 11% of the shorebird populations in this corridor show long-term population declines, while globally 45% of the shorebird populations that breed in the Arctic are declining.

In addition, an article published in the journal Science in 2019 reports that wild birds on the American continent have decreased by about 30% from 1970 to the present, which translates into the cumulative loss of nearly 3 billion birds.

Both texts recognize that the presence of these species is an indicator of environmental health and ecosystem integrity. It is also noted that, as long as shorebirds have lagoons, estuaries, mangroves and other habitats in a good state of conservation, there will be means of subsistence for humans, including ecosystem services. For example, there will be greater fish production, protection against floods and storms, water filtration, and mitigation of climate change, among others.

That is why Cornell University, New York, became interested in incorporating the Huizache Caimanero into the conservation strategy being implemented since 2018. This includes coastal sites in the 14 countries that make up the Pacific Migratory Corridor, where 170 priority zones have been identified.

The prioritization was done through the Ornithology Laboratory’s Coastal Solutions Fellows Program, in collaboration with the David & Lucile Packard Foundation. The strategy consists of sponsoring studies by early-career researchers, to identify the main threats to coastal ecosystems important to migratory shorebirds and to propose effective solutions. It also seeks to establish partnerships for implementation with the public, social and private sectors, explained Osvel Hinojosa-Huerta, director of the program.

He said that, since the program’s launch, 24 multidisciplinary conservation projects have been awarded in different Latin American countries, six each year. Of these, seven correspond to coastal wetlands in Mexico, three of which are in Sinaloa, three in Baja California and one in Baja California Sur.

The Lagoon is Changing

Coastal engineering specialist Román Canul Turriza leads the conservation project of the Coastal Solutions Fellows Program in the Huizache Caimanero. After two years of investigation, he concluded that the collapse of fishing activity is the result of serious environmental deterioration of the lagoon system. Its main problem is silt, a product of the deforestation of dry forest and mangroves that have been replaced by farmland and aquaculture farms.

Devoid of natural vegetation, the soil erodes and causes an increase in sediment carried by the rivers and streams that flow into the lagoon, thus reducing its storage capacity, he explained. As a result of this silt, 3,000 hectares of the lagoon system already have been lost.

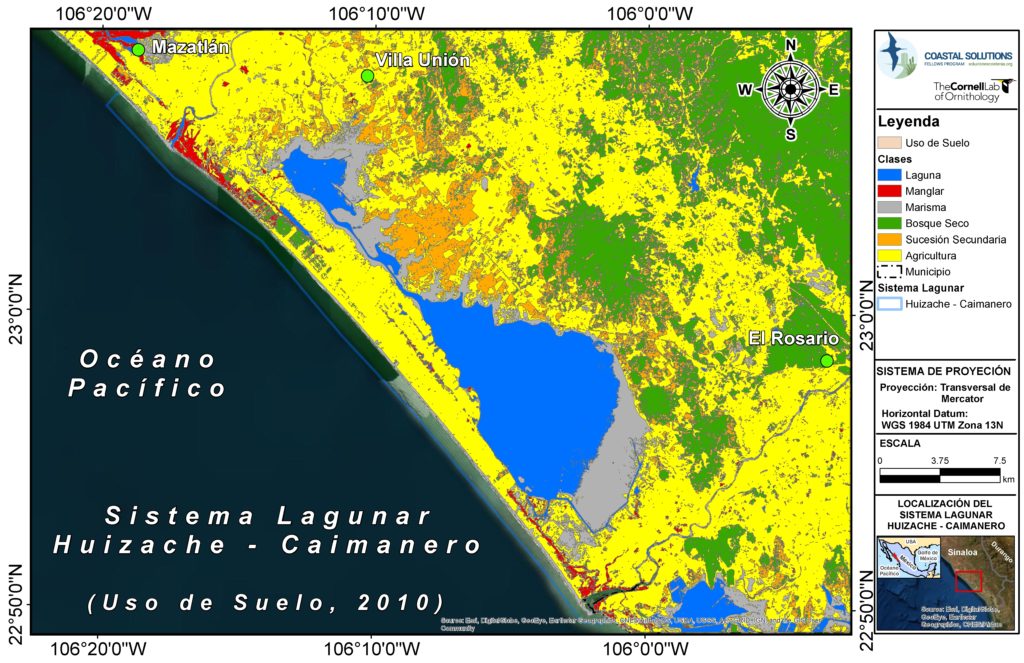

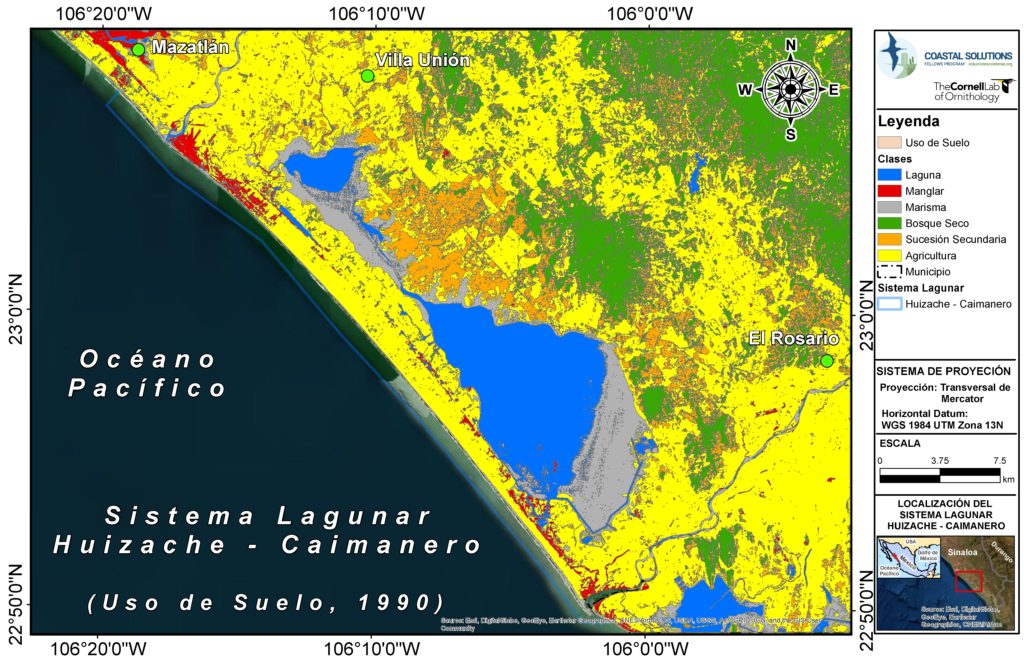

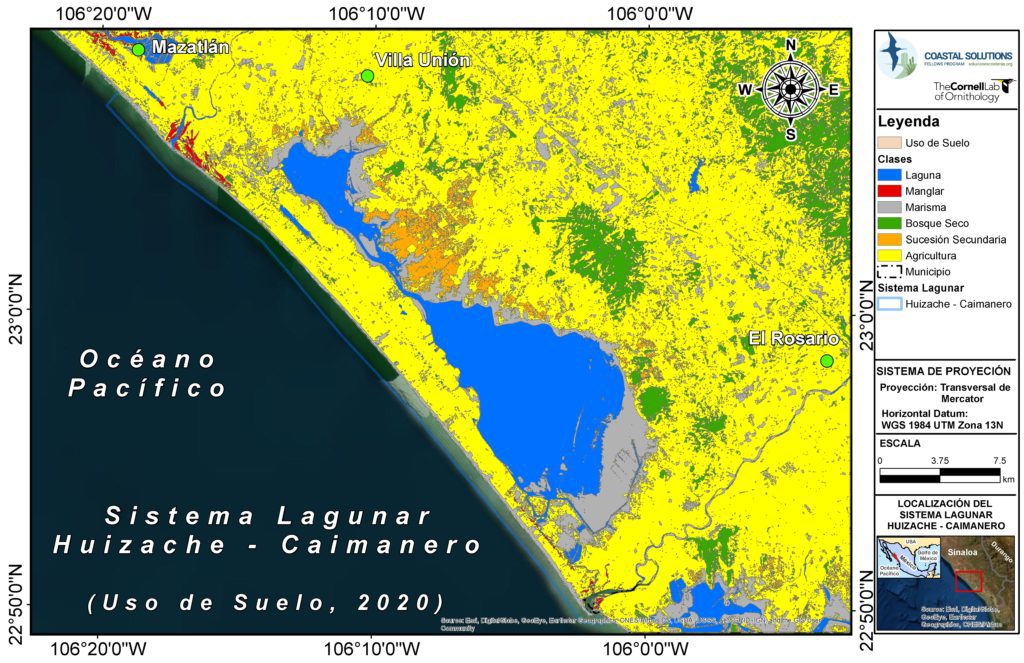

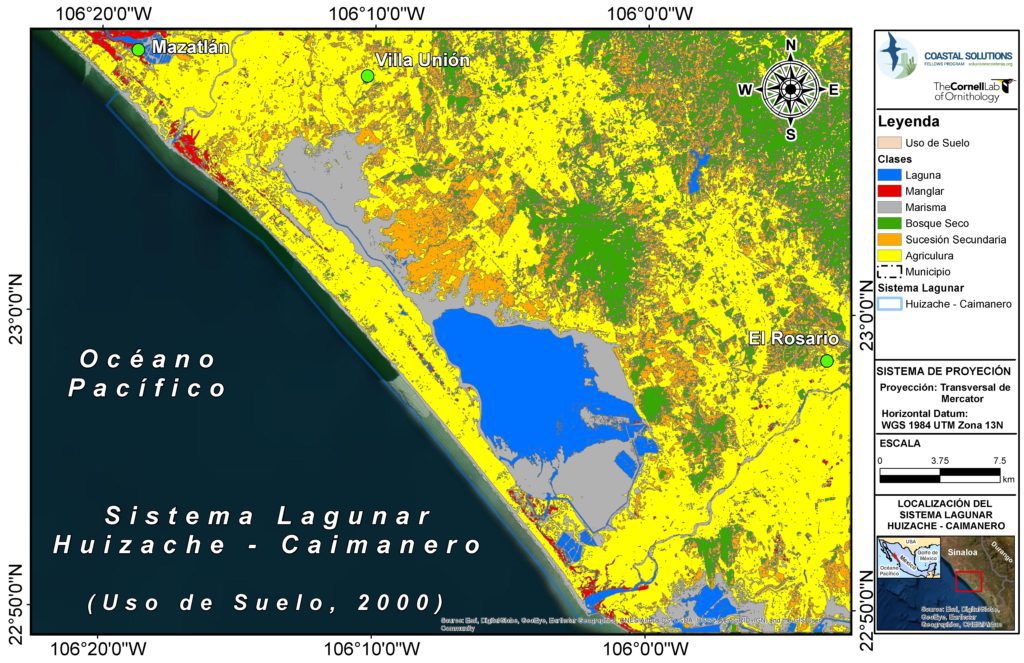

Through satellite images from 1990 to 2020, it was detected that the siltation rate increased 500% in the last decade, going from one centimeter to five centimeters per year. Canul Turriza warned that, at this rate, the Huizache Caimanero could disappear in 15 years.

“In 1984 there were depths of a meter and a half on average in the lagoon, and now we have 60 centimeters,” he revealed.

Remote sensing tools also show that mangrove forest coverage was reduced by 78% and that 85% of the land surrounding the lagoon is agricultural, where mango, tomato and agave crops predominate. In addition, the transformation of the site caused an increase of at least 5°C in the surface temperature of the water, which in turn favors evaporation and a loss of depth.

Land use maps from 1990 to 2020 show a reduction in mangroves, while dry forest and secondary vegetation (scrub/shrub) have been incorporated into the farmland surrounding the lagoon system. The water surface varies depending on the rainfall recorded in each period, however, the current average depth is just 60 centimeters.

This coastal lagoon, of approximately 48 thousand hectares, receives fresh water through the estuaries that communicate with the Presidio and Baluarte rivers. Its hydrodynamics were altered, however, by the construction of a jetty at the mouth of the Baluarte river, which traps the sand and prevents the entry of water and of shrimp larvae. The fishermen say that the jetty was built almost 30 years ago, but they don’t know why; the only thing they know is that the work done with stones from the bottom of the water to form a breakwater has brought them harm.

The natural flow of the lagoon has also been interrupted by the use of prohibited fishing gear such as the so-called “chacuacos” (weirs), funneled nets that function as death traps for any aquatic organism.

The results of the diagnosis were presented to fishermen and authorities of the three levels of government on June 16 in the municipality of Rosario. Right there, a management plan was proposed for the productive restoration of the lagoon system, which highlights the de-silting of critical sites through dredging, the removal of prohibited fishing gear, and removal of the breakwater located at the mouth of the Baluarte River.

Solutions include reforestation in the mangrove area, streams, and lagoon margins; habitat conservation; and bird watching as an ecotourism activity that generates additional income for fishermen and their families.

If carried out, the conservation strategy will benefit the fishing communities and all forms of life present in the lagoon, estuaries, mangroves, dry forest and marshes associated with this system, assured Canul Turriza. To realize this project he relies on the support of the Institute of Engineering of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the civil association Conselva, Costas y Comunidades (preserves, coasts, and communities).

Now that there is a proposal for a solution with scientific support and a workplan, the challenge is to obtain the resources to carry out the strategies and articulate all the dependencies and organizations that intervene in the process.

“Help us fix the lagoon”

Both the siltation and the use of prohibited fishing gear had already been publicly denounced by fishermen in previous years. In response, they obtained mitigation based on eventual dredging in the lagoon and at the mouth of the rivers.

This year, the state government dredged the mouth of the rivers so that the water and shrimp larvae could enter, so the fishermen are hopeful that there will be production and the ban can be lifted. If they are not supported by machinery, more fishing seasons may be lost.

“You see little shrimp, but we have good hope because the river mouths were opened in a timely manner, thank God,” exclaimed the fishing leader Gilberto Palafox Uzeta.

On the other hand, illegal fishing gear has never been regulated. It was the crisis that motivated the cooperative members to reach an agreement so that the weirs stop being used on the fishing grounds of Álvaro Obregón and Laguna del Caimanero. However, the fisheries are still open because no authority has gone to close them, commented Palafox Uzeta. In this regard, the undersecretary of state fisheries, César Julio Saucedo Barrón, clarified that they will not be able to intervene in the lagoon with machinery until a permit is processed before the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat).

The fishermen recognize that contamination generated by the discharges from aquaculture farms, larvae laboratories, mango packing plants, and agrochemicals used in the crops damage the lagoon and reduce production.

Palafox Uzeta considered that the authorities, especially the federal ones, have tolerated these irregularities, and it is they who have the power to remedy them. Another example of this is the installation of the breakwater, he said.

In different forums, the Cooperative leaders have stated that, to overcome the economic adversities that the collapse of production has generated in the fishing communities, they don’t need temporary assistance, but rather the restoration of the lagoon system.

“If it’s a great expense for the government to support us in this, that, and the other, well, let them no longer give us support – but help us fix the lagoon. From there, we are not going to ask for anything, we’ll move ahead on our own. Why do I want a Bienpesca (government stipend) of 7,200 pesos per year, if in a good season I can get 100 – 200 thousand pesos depending on how the production is”, pointed out the president of the Federation of Fishing Cooperatives “United for the Caimanero Lagoon”.

Who will take charge?

Now that there is a comprehensive plan for the productive restoration of the Huizache Caimanero, the next step is its implementation. But to achieve this, it is necessary to manage the resources. The project must be integrated into the public policies of the governments and its continuity ensured through the actions of the academics, fishing cooperatives, authorities and organizations of the public and private sectors. This is the work that Conselva, Costas y Comunidades carries out as part of the conservation strategy.

“This social and political support is what we consider to be the only thing that will take this from being a research project to an intervention project,” said Sandra Guido Sánchez, executive director of the civil organization.

A first step to facilitate the intervention of the different authorities is the preparation of the Ordenamiento Ecológico Territorial (intergovernmental territorial ecological plan) for the Municipality of Rosario, which will serve to regulate the use of land and productive activities for the protection of the environment, the preservation of resources and their sustainable use within the municipality.

Sandra Guido explained that this regulation seeks to protect the lagoon system and its area of influence, including the basin that provides it with water through stormwater runoff upstream.

For the moment, there is already an intersectoral working group and the support of senators and local deputies who have committed to managing resources, aid, and permits through the different government agencies.

“We need the Secretary of the Navy, for example, to support us with dredging, and that requires a whole process that is not familiar to all of us,” she added.

Throughout this process, citizen participation will be key, which is why it is hoped that fishermen and communities are well informed of the strategies and take ownership of the project.

“Citizen participation is the only thing that guarantees that the projects will go from one three-year period to another, from one six-year period to another. That is why it is important from the beginning that there is a lot of citizen participation and a lot of clarity as to what is to be achieved, why, and for what,” she mentioned.

Sandra Guido stated that Conselva agreed to participate in the project because she saw interest from the fishermen and because there are technically supported solutions that make it possible to rescue the Huizache Caimanero.

“We know that we will not be able to return to what it once was, but we are betting that the important environmental services that the system still provides can be maintained,” she said.

Separately, Osvel Hinojosa-Huerta, director of the Coastal Solutions Fellows Program, recognized that for the projects to achieve their goal, it is essential that they have the support of civil society and the different sectors.

“They have to spend a lot of time on governance and on long-term continuity. That’s the basic principle,” he clarified.

The research sponsored by the Laboratory of Ornithology of Cornell University lasts two years. However, the development of the process must continue for 15 or 20 years with social support, without stopping due to changes in government, he specified.

The Resources

In order to dredge the lagoon, as proposed in the Hydrogeomorphological Management Plan of the Cornell Lab’s Coastal Solutions Fellows Program, which will require an approximate investment of 1.5 million pesos, it is necessary to carry out studies to evaluate the environmental impact.

Local deputy Juan Carlos Patrón Rosales, president of the Fishing Commission in the Sinaloa State Congress, said that the studies could be financed with special resources resulting from a budget reallocation that is already being negotiated with the state government and that, if achieved, they would be available this year. In addition, efforts will be made to identify resources for the project within the 2023 expense budget.

For her part, Rosario municipal deputy Rosario Guadalupe Sarabia Soto, member of the same commission, commented that the total cost of the restoration work is still unknown, although they have already begun to estimate costs with different specialized companies. Once the amount is defined, the investment will be tripartite, with the participation of the three levels of government.

In search of resources, the State Secretariat of Fisheries recently had a meeting with international organizations that are interested in supporting charitable projects in the Gulf of California, revealed Undersecretary Cesar Julio Saucedo Barrón.

They are Coming

While the fishermen of the Huizache Caimanero wait for the shrimp to gain size, migratory birds are on their way. Both will depend on the lagoon for their subsistence.

From August to March or April, between 100 and 120 species of migratory birds converge on this coastal wetland, sharing habitat with at least 100 other resident species. This diversity is possible thanks to the fact that the lagoon system has a variety of marine and terrestrial environments in which fresh and salt water are available, explained Guillermo Juan Fernández Aceves, a researcher at the Laboratory of Bird Ecology of the Institute of Marine Sciences and UNAM Limnology, Mazatlan Academic Unit.

Here, the most common migratory bird is the Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri), which, weighing just 25 grams, flies between 10 and 12 thousand kilometers from Alaska to northwestern Mexico, said Fernández Aceves. The migration journey lasts between 30 and 60 days; during this time it flies in segments, rests, feeds, and regains strength.

When the winter is over, they will return to the Arctic to breed. The species will do so every year, if it manages to survive the threats of climate change and the destruction of its habitat, always on the same route, faithful to the same place.

These and other shorebirds spend the winter on beaches and mud flats that are exposed when the tides go out, providing access to molluscs, polychaetes (marine worms) and other invertebrates that they capture with their bills. Some species stay in Mexico and others go down to Central and South America, to Chile.

The specialist considered that as long as shorebirds have lagoons, estuaries and mangroves in a good state of conservation, there will also be means of subsistence for humans.

“If there are good lagoons there will be birds and there will be shrimp; then we will have to value the lagoons, keep the water clean, respect the natural habitats and have a more sustainable and orderly management,” he concluded.

This story is our first collaboration with media partner Son Playas, an independent media project covering the coastal ecosystems of the Mexican Pacific. It was reported with the support of the Journalism Network of the Sea (Repemar), promoted by Causa Natura with the help of the Earth Journalism Network of Internews.

- Countdown in Sinaloa: 15 years left to save critical coastal habitat - September 21, 2022

Coastal habitat Huizache Caimanero Mataderos Cooperative Rafael Narval Sinaloa