It is winter and it is hot; the temperature hits 30℃ (82℉). Here on the mountaintops of Mexico’s Chimalapas rainforest region, the climate has changed a lot, owing to deforestation. At the heart of this iconic jungle in the state of Oaxaca, members of the Zoque Indigenous communities of Benito Juárez and San Antonio are doing all they can to reverse the trend. However, new mining projects threaten to tear down their hard-won gains.

This story is the second part in a series by award-winning Zapotec journalist Diana Manzo about community initiatives to preserve one of Mexico’s most biodiverse forests. See Chimalapas: Building community to save a forest to learn more about this iconic forest and the historic efforts to preserve it.

Para leer este artículo en Español haz click AQUÍ

The journey to these rural enclaves, situated at a distance of 15 kilometers from each other, is a tour of deforestation’s effects. In addition to hotter weather, the surface and underground water courses are being altered. Erosion and ongoing flood damage to the highway mock the very idea of construction crews.

“The rivers don’t flow slowly as they did before; the uncontrollable floods make them threatening,” says Maria Garcia, a community member from San Antonio. Defending the territory against illegal logging and forest fires is not easy, she says. For example, in 2011, the Environment and Natural Resources Ministry granted 12 logging permits for four squatter ejidos and eight for private property owners occupying communal land in San Miguel and Santa María, Chimalapa.

“We do not want ejidos or private property on our lands,” she says. Yet, in the boundary disputes that have plagued the area, Garcia favors dialogue. In her opinion, as with most of her indigneous neighbors, the land has no owners, neither from Oaxaca nor from adjacent Chiapas state.

Photo: Diana Manzo

Garcia arrived at the age of three, from the western state of Michoacán, and as an adult she joined the fight for the Zoque jungle. Since then, the community forestry effort has come a long way in the service of habitat recovery.

A tall woman with silver hair and a firm voice, García says that she has been a guardian of the forest all her life. “I have given myself to the defense of the forest, because I have my house and my children living here,” she says. At 65 years of age, she is also a midwife and seamstress in the community. She says that for the forest she has been persecuted, threatened and even imprisoned.

“But it is worth it all,” she insists. For four decades she has been walking the paths of the forest, and together with other community members, she takes part in surveillance activities.

“I put on my rubber boots, my hat and I go with my colleagues,” she asserts. Reflecting on the Oaxaca-Chiapas border conflicts and the influx of new residents, she yearns for their resolution. Her biggest dream is “not to leave problems for my sons and daughters.”

As part of Mexico’s world-renowned community forestry model for sustainability, the example of the Chimalapas shines. It has produced important results in conservation of a natural biosphere considered one of the most important lungs of Mexico.

In 2010, the community members obtained a permit to extract resin in the protected area of El Cordón del Retén. This sustainable use of forest resources has helped them to survive without damaging what they love most, their forest.

PALM FROND HARVESTERS TURN TO RESIN TAPPING

The illegal exploitation of a plant called xate, or camedor palm, lasted more than a decade in the Chimalapas, says a study called “Camedor Palm and Cicadaceae or Traffic of Oaxacan Flora” published in 1995, by biologist Rafael Cardenas.

Known by scientific names such as C. pinnatifrons and C. quezalteca, these species are classified as non-timber plants in danger of extinction.

Cardenas explains that adorning houses in the United States and Europe with floral arrangements of this ornamental plant stripped resources from the Chimalapas communities of San Antonio and the Chiapas ejidos of Díaz Ordaz and Rodulfo Figueroa.

In his document endorsed by the Environmental Studies Group (GEA), the author points out that the logging business of the Gil Toledo family, from adjacent Puebla state, led the camedora palm enterprise in the Chimalapas. Its headquarters were 40 minutes from San Antonio and Benito Juárez.

Mauro Vásquez, a community member from San Antonio, still remembers that his father told him how strangers used to come looking for the “palmita” to decorate their centerpieces, but he didn’t realize that they were selling it in volume.

In 2008, the National Forestry Commission published a diagnosis on the situation of the camedor palm and plantation management technology. It revealed that the community of San Antonio had nine varieties of palms. With the analysis, meetings, and agreements, the agency managed to stop the illegal sale of the camedor palm.

“We were destroying the forest,” Vasquez recalls his father telling him. He also remembers how the biologists and activists arrived in the area to prepare a preliminary analysis.

Among them, advisors from the World Wildlife Fund offered counsel to the community members. That is when they became aware that the sale of the camedor palm was looting the forest. After this analysis, in 2004, they signed the Master Plan, which designates 10,000 hectares of their territory as a Voluntary Natural Conservation Area.

According to the document “Harvesting Sustainability In Chimalapas”, Conservation International helped hatch the plan to extract resin as a sustainable source of income, alongside WWF and community members of both San Antonio and Benito Juárez.

“Not everyone wanted to (desist from the looting), because it was a lucrative business,” explains Vásquez. He recounts that his father, together with other community members, decided to instead tap the pine resin and market it for a collective income, after learning it was an alternative for survival.

When the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (Conanp) established the Voluntary Natural Conservation Area, the community began resin extraction on a commercial scale on the 10,000 hectares known as El Cordón del Retén. That has helped protect an important variety of precious woods, birds, and virgin territory of the Chimalapas. The activity keeps out clandestine logging and trafficking of wildlife, in particular of the jaguar. The community members dispense the resin in bulk, mainly in the state of Michoacán.

“We came to understand that we can live from the forest without finishing it off, without damaging or mutilating it,” Vásquez relates.

The resources available to the community watch brigade for El Cordón del Retén are nothing when compared to the size of the area and the size of the threats to this community reserve – among them, land invasion, illegal logging, and related fires.

However, from the resin industry, the community has managed to take care of the forest, while also reducing competition among and differences between communities, according to Vásquez.

In “Use of Pine Resin in the Eastern Zone of San Miguel Chimalapa, Oaxaca: From the Conservation of Natural Resources to Sustainable Development,” Adriana Zentella Chávez explains how this socio-economic activity has supported natural resource conservation beginning more than a decade ago.

She details the creation of two rural production societies: El Cordón del Retén San Antonio Agricultural and Forestry Producers and the Union of Environmentalist Agricultural and Forestry Producers Río Portamoneda Benito Juárez Chimalapa. Each one established a Committee for the Use of Pine Resin. With 35 community members including Vásquez, they reap equitable profit shares, she narrates.

COMMUNITIES FACE UPTICK IN CONSERVATION THREATS

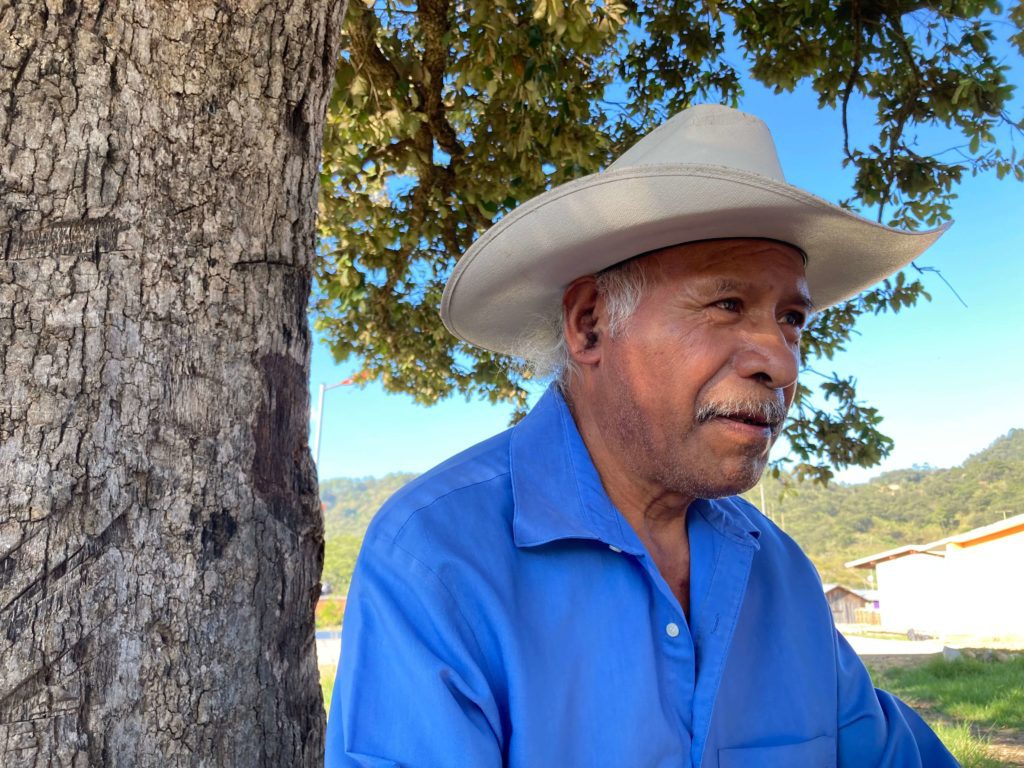

Like Garcia and Vasquez, Alberto Matus Ramírez was a child when his parents, from Miahuatlán, Oaxaca, arrived in Benito Juárez, Chimalapa – eight hours away – to work at the Sánchez Monroy sawmill. About 30 people lived there, he remembers very well. Ramírez today is 69 years old, a community member and defender of the forest. He shares the inheritance with his two children, who carry on the crusade to prevent further encroachment on the territory.

A straw-colored hat distinguishes this man among the others. Sitting on a downed branch under an oak tree, he recalls that this spot is where the community members held the assembly that led to their boundary dispute settlement. They collected signatures and sent them to the federal Supreme Court. The result was the ruling last November to return to Oaxaca 160,000 hectares in possession of the neighboring state to the south, Chiapas. Community members venerate this leafy tree, which they say keeps the historical secrets of more than 40 years of struggle for territory.

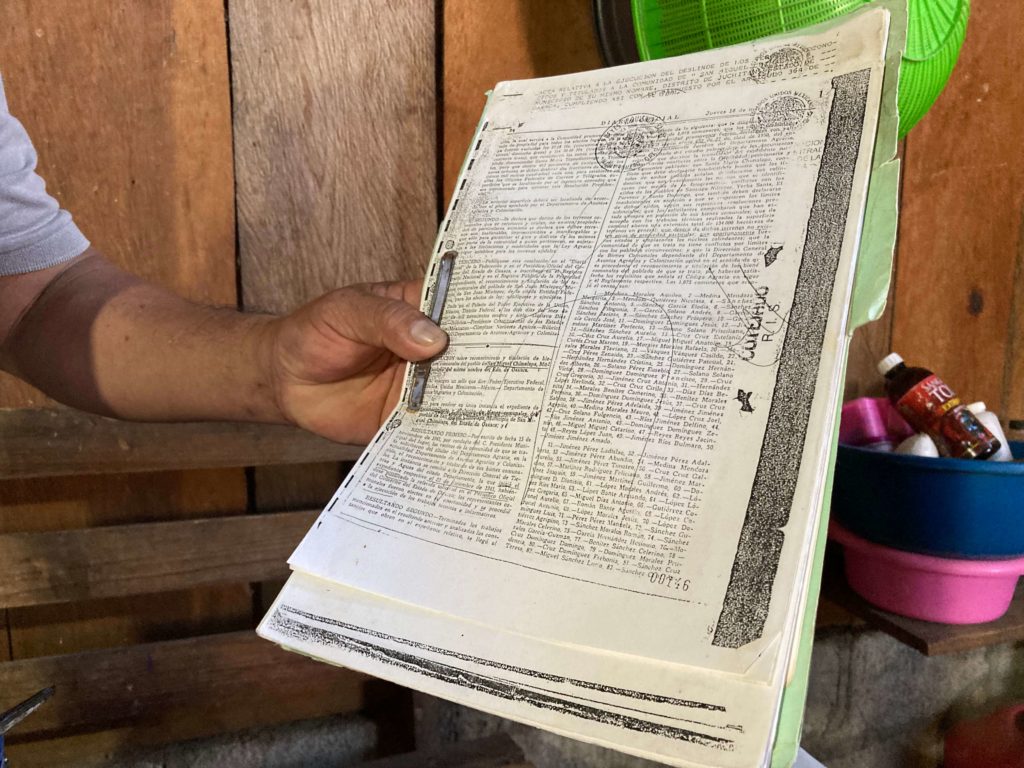

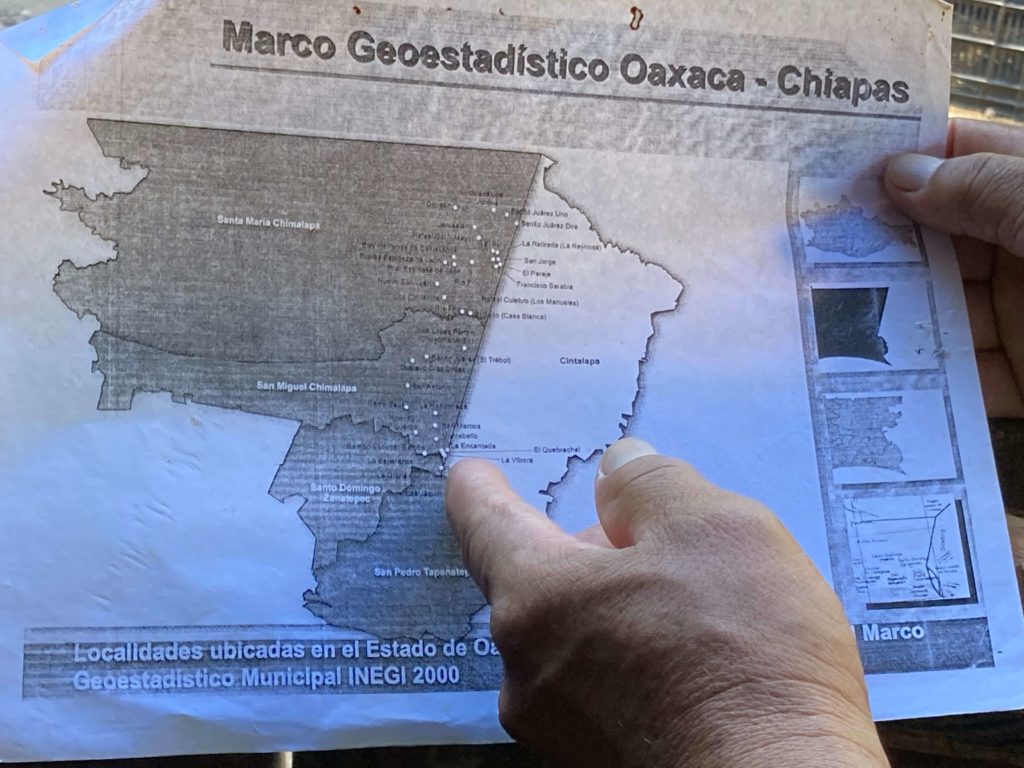

Emiliano Pérez Gutiérrez also arrived here as a child and is a veteran defender of the territory. He is 58 years old and lives in San Antonio. On his kitchen table, he displays maps and documents. Regardless of his valuable contributions to the community, it is still facing challenges. Among them, the illegal loggers keep coming back, and now the transnational mining companies are closing in, bringing with them more habitat destruction.

Joining him is Miguel Angel García Aguirre, representative of the organization Maderas del Pueblo, activist and researcher of the Zoque territory of Chimalapas. He notes that in 2021 the magistrates of the Supreme Court ratified the return of lands to Oaxaca. They confirmed that Chiapas violated territorial limits based on a 1549 map in which the Spanish viceroyalty and captaincy set an historical precedent.

Even so, the activist warns, for example, that a rancher from Chiapas recently wiped out eight hectares of pines, oaks and tropical trees in the area called Las Águilas, in front of the El Quebrachal Community Congregation, San Miguel Chimalapa.

In January, loggers guarded by a group of armed people razed the trees on that site – source of the spring that supplies water to a vast area around it, according to Garcia. Burning to clear land for cattle ranching and agrarian plots contributes to the loss of jungles and cloud forests.

Since November, The Esperanza Project has requested from Conanp and the Federal Environmental Protection Agency information on the preservation and clandestine logging of the Chimalapas, with no response.

Meanwhile, says Alfredo Aaron Juárez, director of the Oaxaca State Forestry Commission, forest fires have seriously damaged the Chimalapas. He points out that each year endemic flora and fauna of the region vanish. In 2020, a forest fire in the area lasted 30 days, affecting 142 hectares between Cerro Azul and Cerro Atravesado, a border area of Chiapas and Oaxaca.

If that were not enough, now mining threatens the Chimalapas, alerts the Matza collective, made up of young Zoques from the community of San Miguel Chimalapa.

Five mega mining projects are slated for the southeastern part of the communities’ territory. The Ministry of Economy already has authorized the Santa Marta concession with an area of approximately 7,000 hectares.

Josefa Sánchez Contreras, community defender and member of the Matza collective, denounces the federal government for failing to inform or consult with the community members about the mega mining project; federal protocol was breached, she says.

The Ecology Gazette, official bulletin of the Environment and Natural Resources Secretariat, recently published the advent of the four other proposed mega mining concessions. They appear on the website of the Ministry of Economy, on the page Carto Min Mex, as part of a tracking system developed by the cartography department of the General Directorate of Mines. The mining industry’s public property registry here shows an attempt to take over more than 105,000 hectares in Chimalapas. If the concessions are exploited, it would transform almost the entire Zoque territory of San Miguel Chimalapa – 134,000 hectares.

Sánchez Contreras stresses that failure to respect community tenure violates international and federal guidelines for informing the Indigenous residents about these new applications and mining concessions.

“The Santa Marta concession is highly toxic for the biodiversity of the region and for the Zoque Peoples, but also for the Zapotecs and Ikoots, since the copper, silver and gold extraction sites are located at the headwaters of three rivers, the most important being the Ostuta,” she says. “If their exploitation is allowed, they would be lethally contaminating the Huaves’ upper and lower watersheds, which is where the Huave people base their culture and life,” she explained. “So that is why we are denouncing this arbitrary process.”

This story was reported and produced with the generous support of the One Foundation.

- Land defenders caravan to Mexico City to defend Chimalapas - June 29, 2023

- Agroecology Center revalues agriculture – and culture – in Oaxaca - February 16, 2023

- Community Foresters Unite to Save Biodiversity Hotspot - April 19, 2022