It’s been a decade now since Mexico experienced its Standing Rock moment. It was the native Wixárika people—better known internationally by their Spanish name, the Huicholes—who galvanized a global movement with their call for help. In the north-central state of San Luis Potosí, one of their most sacred sites—the Birthplace of the Sun—was being readied for exploitation by Canadian mining companies.

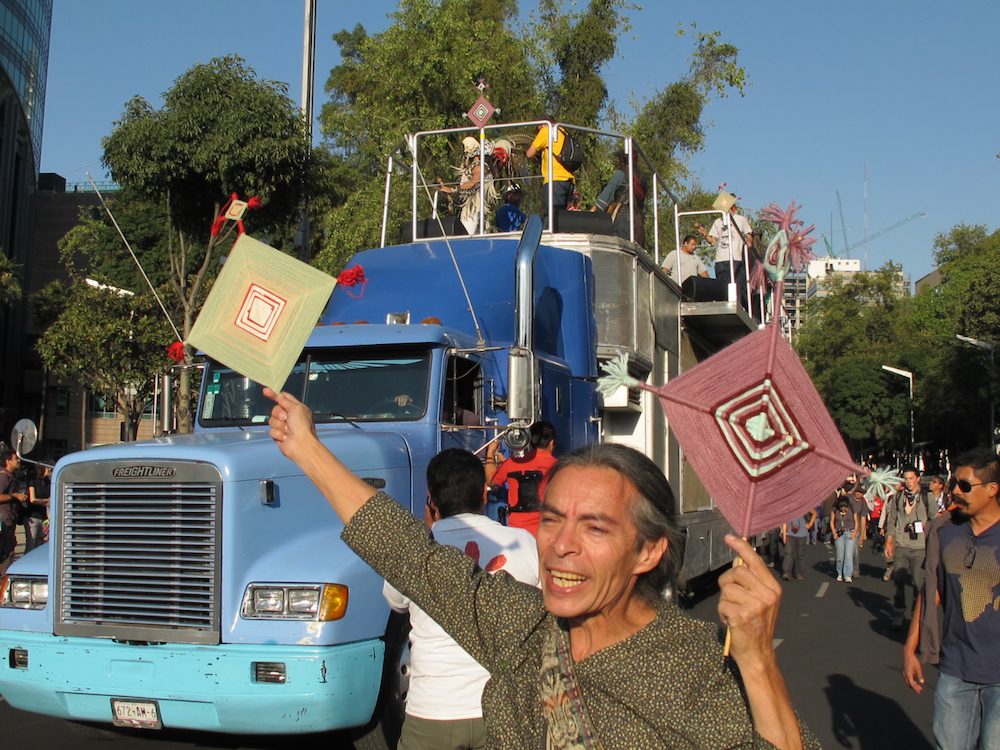

Santos de la Cruz Carrillo, at that time a leader of the Wirikuta Defense Front, stands in the background in his ceremonial clothing. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

To the Wixárika people, Wirikuta—the Sierra de Catorce mountain range and the desert at its feet—are both a university and a temple of prayer. It’s the destination of an ancient pilgrimage made every year, when thousands of families pack their bags and travel—by bus, by pickup truck or van, and then by foot—from their homelands in the Western Sierra Madre, 400 miles east, to the desert to hunt for their sacramental peyote.

According to carbon dating of the ashes from their ceremonial fireplaces, the Wixárika have been in this region for at least 15,000 years. The ritual of collecting and consuming peyote in this land is literally woven into their origin story. The Wixárika believe each step on this journey and each stop at one of the sacred springs that dot this desert renews the essences of life and the reciprocal relationship between humankind and the more-than-human world.

Para leer este artículo en Español haz click AQUÍ

The prospect of not one but two transnational mining companies laying dynamite to this delicate web of life presented them with an existential threat. The response was swift, multitudinous, and heartfelt. Spiritual seekers and psychedelic adventurers from Europe, North America, and as far away as Japan had partaken of Wirikuta’s magic—many through the recreational (and illegal) “peyote tourism” that occurs with non-indigenous guides, despite periodic law enforcement crackdowns, and others in a more authentic context with Wixárika ma’arakate or shamans. They wanted to help.

Academics, artists, and environmentalists from across Mexico and beyond stepped up to support the effort. In the course of the next two years, a coalition called the Wirikuta Defense Front, led by the Wixárika authorities themselves, built a wave of support that generated a massive march in Mexico City, a historic mass pilgrimage to the sacred site— where they believe their ancestors were guided by the Gods to first discover peyote—and a series of Wixárika delegations seeking support in far-off lands.

There was Wirikuta Fest, a daylong rock concert in Mexico’s Foro Sol with a full lineup of Mexico’s top recording artists—Café Tacuba, Calle 13, Caifanes, Enrique Bunbury, and many others—drawing upwards of 60,000 people to raise money for sustainable development projects in the desert as an alternative to mining. There was a full-length feature film by Argentine filmmaker Hernán Vilchez, Huicholes: The Last Peyote Guardians, which detailed the saga, won awards, and made a world tour. There was also a lawsuit, filed by the Wixárika community of San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán, requesting a suspension of all mining activities on the sacred site. The activities culminated in a Federal Court ruling in June 2012 that provisionally granted that request—a ruling that was extended in July of last year, though it is still provisional.

The court ruling put a halt to the exploratory drilling and preparations of the mining companies, at least to the present day. It did not, however, put an end to a multitude of threats that persist in the region, and the UNESCO designated site has suffered an assault from industries including an aggressively expanding agriculture industry, peyote tourism, hazardous waste disposal, massive wind farms, and narcotrafficking.

Wirikuta and the whole region, referred to as the Altiplano or the high plateau of San Luis Potosí, has been a magnet for industrial megaprojects since the colonial era. In the 1700s, it was a silver mining area, with the picturesque mountain village of Real de Catorce as its hub; the former ghost town turned tourist attraction is emblematic of the boom and bust cycles that have played out there for centuries.

Diana Negrin of the Wixárika Research Center, professor and geographer at the University of San Francisco and daughter of longtime Wixárika researcher and supporter Juan Negrín, grew up seeing Wirikuta as a place rich with abundance that goes far beyond the silver and gold that lie beneath the surface.

“It’s presented as a place of lack, a place that needs an intervention,” says Negrin, who hosted a webinar in August called “A 10 Años de Wirikuta: Los Pueblos del Gran Nayar” (Wirikuta 10 years later: The Peoples of Gran Nayar). This has led the area—like deserts everywhere—to be considered a sacrifice zone for modern industry. But Wirikuta is home to the greatest concentration of biodiversity in the vast Chihuahuan Desert, and one of the most biodiverse deserts in the world. That biodiversity is diminishing with every hectare plowed under for the vast tomato and berry greenhouse operations, the industrial egg farms, and a recent spike in illegal peyote harvesting.

Researcher Pedro Nájera of Conabio (the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity) has presented troubling evidence that this sacramental plant at the heart of the Wixárika cosmogony is rapidly disappearing. Nájera, a native of San Luis Potosí, did a five-year study monitoring 70 different sampling areas within the protected area of Wirikuta and other sites in the Chihuahuan Desert. His study tracked an alarming drop in the number of peyote buttons, finding that 50 of the 70 sites were severely impacted, with a 40 percent reduction in the number of cacti counted. He predicts peyote’s possible extinction in the wild within as little as a decade—if current trends continue.

In his view, shared in a 2018 interview for Intercontinental Cry, the decline in the species derives from “the anthropocentric vision we have towards things, because we view them in terms of the function of what benefits us, or makes us feel good…(that people) believe, in some very strange way, that the soul magnifies itself while driving a species to extinction.”

Eduardo “Lalo” Guzmán lived and studied with the Wixárika for many years before becoming a longtime inhabitant of Wirikuta and later, a leader in its defense. The peyote is fundamental to the Wixárika way of life, he said. “They were given the mission of protecting nature through their practice of pilgrimage, planting, hunting, the task of keeping the flame alive, the burning embers, of all the memory of all the ancestors. And that is what allows their existence in the present. So life is not understood without the existence of that plant.”

The multifaceted attack on the desert has led to a degradation in not just the physical plane, but the energetic quality of the place as well, says Miguel Carrillo Gonzalez, a traditional judge from the Wixárika community of Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán. “It’s really sad. I remember in earlier times when I used to go, there was so much life. Nowadays, it’s not the same, you don’t find the same plants, the same animals. With all the people who go there, it’s really changed, not only the landscape, even the energy is different from how it used to be.”

Susana Valadez, anthropologist and founder of the Huichol Center for Cultural Survival, married into the tribe in the 1990s, returning for the first time after many years with her family to discover that a chaos had emerged around the pilgrimage, with tourist buses pulling up alongside the sacred springs where Wixárika families gather to pray. “While the shamans and pilgrims sit around their ceremonial fire and chant the messages of the creators, the tourists roast hot dogs and drink beer at their adjacent campsites,” says Valadez. “It’s become a circus.”

Since time immemorial, Wixárika pilgrims have fashioned elaborate votive art to leave as offerings at each of the sacred springs and other sites along the path of their pilgrimage as they retrace the steps of their ancestors. “Many times our offerings don’t even last a day; people come and take them away,” he says. “It’s just impossible to control the influx of tourists; everyone wants to go there now. All of this dissipates the energy.”

Another thing dissipating the energy is the gradual disappearance of the “family clusters” of peyote, says Valadez. “The big clusters embody the spirit of the deer who provides the portal for them to access the spirit world. No clusters, no access. There are many different kinds of peyote, with different usages…when over-harvesting occurs, the availability is limited, and the energy of the magical habitat is diminished. It takes many years for these clusters to replenish.”

These days, with the Wixaritari sheltering from COVID in their mountain homes, it’s the non-indigenous inhabitants of Wirikuta who tend to be on the frontlines of these more dispersed threats—as they have always been, but without the media attention that the Wixáritari are more capable of attracting.

Iracema Gavilán, a Mexican academic and expert witness who has accompanied the defense of the desert since the beginning of the struggle, says the campesinos or peasant farmers of the region have the deepest knowledge of environmental conditions, and are the ones who suffer the most with the impacts of climate change—a current reality with drought worsening in the region.

Many believe it’s being made more severe by industrial growers’ practice of using controversial devices called hail cannons to disperse the clouds. This practice, together with the aggressive extraction of groundwater necessary to irrigate the crops, is leading to a water crisis in the region, say local residents. In the area of Valle de Arista, for example, the underground aquifer fell from 40 meters below the surface to 400, according to a book by anthropologist Javier Maisterrena Subirán at the Colegio de San Luis Potosí. The National Water Commission (Conagua) has also revealed that six out of 10 aquifers in the Altiplano region are overexploited, according to Mexican newspaper La Jornada.

Those same campesinos have organized to stop the practice, succeeding last year in getting legislation passed to ban the use of hail cannons until more research can be done into its effects. They have also organized to stop the installation of a hazardous waste disposal facility, and several municipalities have passed resolutions declaring themselves mining-free zones. The Catholic Church’s social pastoral committee took a leading role in the fight against the toxic waste facility, with Cedral’s Father Gerardo Ortiz at the forefront, leading to the unusual collaboration of Wixárika authorities with church leaders.

“For the Wixárika, this is sacred territory,” says Ortiz, “but for us, it’s sacred land, too. It’s what feeds us and sustains us, and it has a very special way of being. That’s why we call it Mother Earth.” While some Catholics shy away from political involvement, Ortiz felt vindicated by Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Sí, and subsequently Querida Amazonia, which discussed the need to defend our common home.

The mining threat has far from receded, however, the Father reported. Small-scale antimony mining has had serious environmental consequences that have not been monitored. And mining company representatives continue to show up at community meetings, moving ahead with their campaign to convince the locals that mining is a part of their heritage and laying the groundwork to begin work as soon as they can get a favorable court ruling.

To Gavilán, the future of these lands is inextricably linked with that of the planet. In part, she says, because the destruction of the desert has serious climate and biodiversity implications; but on another level, because the desert itself, and the sacred cactus endemic to it, has the capacity to heal the spiritual sickness that has afflicted human souls.

Like many others, she dreams of a joint project between Wixárika leaders and local campesinos that would revitalize the local economy by creating community-based peyote restoration and conservation programs. These programs would combat the problem of looting peyote by providing monitoring, education, and reforestation projects and access to the medicine in a culturally and environmentally appropriate context.

“I think that all of us should have a certain right at some point to have contact, to commune with one of these ancestral plants, because that will transform us as people, and it will help us,” she says. “Not like a New Age hobby of the cultural consumption of psychotropic plants; there has always been that in the history of mankind. But with the intention that it will be able to transform us in the sense of valuing our common home, our humanity, even belonging to a territory that is global, but which is also local.”

This idea puts her at the heart of an intense debate over legalization, with some, like many from the Native American Church of North America (NACNA), opposing use of the plant by anyone who is non-indigenous. The concern is that the danger of peyote extinction is too great, and that, like the Wixaritari, their cultural and spiritual identity depends on a continued supply of the sacred cactus.

Najera, with what he’s seen in his years of monitoring, comes down on that side. “There is now a growing number of Wixaritari who claim that appropriation of their culture is the last conquest; after already taking away their lands, water, minerals, and other resources, now the Westerner, as a good descendant of the conquistadores, seeks to appropriate their biocultural resources and even their religion.”

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026