AGUASCALIENTES, Mexico — Eustolia Guerrero helps organize cleanup campaigns in the small rural community of Los Parga on the outskirts of Aguascalientes state’s capital. Through the years, she has defended the wild mesquite trees in her environment. Among her stores of knowledge is the recipe to make gorditas with meal from the pod of these trees native to this arid region in Mexico’s central highlands. Gorditas are a local specialty, usually consisting of a cornmeal and lard mixture formed into thick cookie-like rounds and deep fried to puff up for stuffing with savory fillings, such as cheese, beans, meat, or vegetables.

“Add 6 tablespoons of mesquite meal for every kilogram of cornmeal; the water is added as it is kneaded,” she says.

Para leer este artículo en Español, haz click AQUÍ

Guadalupe Castorena Esparza, a native of Aguascalientes, has a recipe to make another rockstar of Mexican gastronomy, adapted to the now unusual ingredient.

“Add 6 to 10 tablespoons of mesquite meal to every kilogram of corn meal,” she reads her instructions.

Another way to take advantage of the mesquite beans’ characteristic sweet flavor is to boil it with brown sugar until a molasses is obtained, then mix it with pinole (dried corn meal ground with cacao beans, sweetener, and spices), and knead the dough to a consistency like conventional marzipan. Beatriz Osorio Urrutia shared her version of what is aptly called mezquipán.

These secrets — and many more handed down through the generations — are documented in the book El Árbol de la Vida: Recetario del Mezquite (The Tree of Life: The Mesquite Cookbook), edited by the Aguascalientes Environmental and Cultural Movement in collaboration with the Cerromuerto publishing house — a project coordinated by this author.

If you want to purchase a copy of the recipe book, send a message to the Facebook page of Editorial Cerromuerto. To obtain a digital copy, download it here, available to the public for free.

The mesquite pod is high in fiber, sugar, and protein, with almost all the amino acids. An excellent source of vitamins and minerals, it has a wide variety of medicinal and culinary uses. It can be eaten alone as a sweet, boiled to make molasses, or dried and ground into meal — in some of its more traditional forms.

Besides capturing and sharing the knowledge of how to cook with mesquite, the purpose of the book is to raise awareness about the value of this ancestral tree that is both a “flagship” and an “umbrella” species at the same time. These terms apply to flora or fauna vital for the survival of many other species, perhaps less well known. The flagship concept implies that the species has been adopted by generations of environmental defenders. In the case of mesquite, the species is deeply ingrained in different cultures whose practices stem from the use of all its parts.

In relation to its ecological importance, its roots fix nitrogen in the soil and prevent erosion. It is adapted to obtain and make efficient use of water even when none is visible. Its root system allows the capture of water where the aquifer may be very deep; its tiny leaves economize the scarce resource; it has one of the highest photosynthetic capacities; it offers shade, food and shelter for different species of fauna.

Photo: Guadalupe Castorena Esparza

Defending the permanence of a mesquite allows it to fulfill its function of providing a microhabitat for other species that otherwise would not prosper in the extreme conditions of the arid climate. Different cultures have used it to guide them in the search for water sources, because its roots can be fed by groundwater.

Photo: Guadalupe Castorena Esparza

Currently, in the organization we have formed, Salvemos La Pona, we are seeking ways to show society the damage done to La Pona, the last stand of mesquite (mezquitera) in the city of Aguascalientes. The idea is to gain support for the argument that saving La Pona is an exercise of collective human rights to a healthy environment. To this end, we are constantly monitoring to prevent approval of construction permits or illegal interventions.

We do a weekly review of the gazettes of the federal and state environmental secretariats, since the Environmental Impact Statements for land use change requests must be listed there. We are in constant communication with neighbors of La Pona, who notify me if machinery enters, if there is fire to report to firefighters, or any other incident. We make freedom of information requests to find out if the municipality has granted construction licenses.

We recently began planning to take direct actions to continue defending La Pona, as we continue to raise awareness about its historical, cultural and biological importance. In addition, we seek to have communication with reliable and up-to-date sources of information to learn about any activity of the municipal or state government that would affect the mezquitera. We are constantly on the lookout for updates of development plans and changes in the catalog of Priority Areas for Conservation.

Mesquite, as well as other native species, have protected status under the environmental regulations of the Aguascalientes City Council. Therefore, developers are required to guarantee the protection of this species when they are engaged in construction projects and other urban projects. The law even specifies that “trees over 30 years old or with a diameter greater than 50 centimeters measured at 1.20 meters high may only be transplanted with express authorization from the municipal government.”

However, there is the possibility of processing and obtaining permission from the State Secretariat for the Environment, Water and Sustainable Development to cut down the trees when there is no other alternative. Another factor to take into account is the under-registration of trees for which permission is not processed for their removal. Currently, in the case of La Pona, the biggest threat to the mesquite has to do with forest fires.

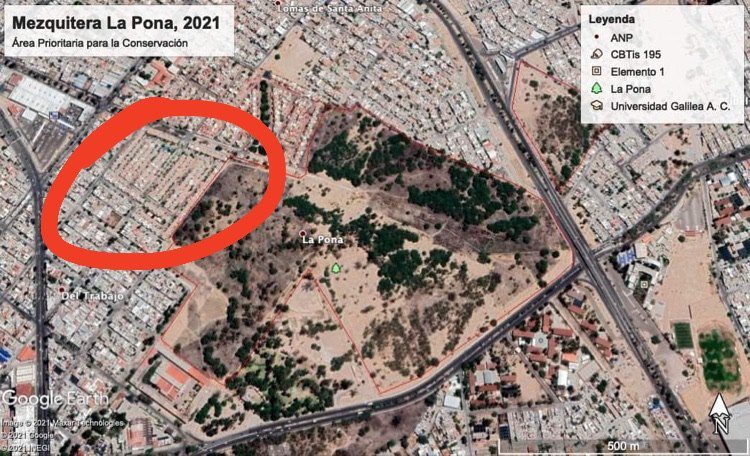

La Pona was included in the 2014 State Catalog of Priority Areas for Conservation with its entire 31 hectares of woodland being listed for protection. This listing restricts possible uses, since they must be compatible with conservation activities. The construction of new population centers is prohibited. It does not, however, imply a management plan or resources for its care.

In 2016 the news spread that only a third of the 31-hectare open space would be preserved. Thus, 20 hectares would be urbanized. So far that has not happened, but many activities have pointed to future devastation.

Due to the lack of definitive and comprehensive protection of the mezquitera, in 2016, a group of people, including this author, formed the organization Salvemos La Pona (Save La Pona). To raise awareness about the threats to the mesquite stand, we are using compelling information. We need to combat the citizen disconnect that occurs in collusion with authorities who ignore the principle environmental problems — such as deforestation, soil erosion and desertification.

Photo courtesy of SOS Mezquitera La Pona AC

In 2018, the Salvemos La Pona collective gave the municipality more than 3,000 signatures from people interested in preserving the entire stand of mesquite.

That year, in the wake of negotiations with previous municipal administrations, an initial project was finalized with Mayor María Teresa Jiménez Esquivel, and the companies that own mesquite land, Inmobiliaria Próxima SA de CV and Patrimonio SA de CV SOFOM ENR. The companies agreed to donate the previously mentioned third, which is equivalent to 11.4 hectares, under the condition that the city council modify the Urban Development Program of the City of Aguascalientes 2040, so that the 20 hectares at stake would be recategorized for urbanization. The municipal government donated six additional hectares to make up a total of 17.4 hectares. As a consequence, only a third of La Pona was declared a Protected Natural Area.

The city’s donation was La Pona Park, located in the middle of the mesquite stand, where the vegetation has been modified to such a degree that it has lost its relictual characteristics of native forest — that is, mesquites and huizaches (among other native species) were cut down and replaced by exotic trees.

In July 2020, the state environment secretariat published a new version of the Catalog of Priority Areas for Conservation, in which the total area of La Pona (31.4 hectares) was ratified. This listing was the only concrete protection of the mesquite stand until Aug. 21, 2021, the date on which the Second Report of Mayor Jimenez responded to citizen pressure with the Declaration and Comprehensive Rescue of Mezquitera La Pona and Los Cobos Protected Natural Areas, under municipal jurisdiction. Even so, this area is an insufficient amount of land to allow for a true restoration.

It is important to note that since 2011, the human rights stipulated in the international conventions and treaties were integrated into the Mexican Constitution. So now all authorities are obliged to disseminate, respect, guarantee and repair them. Since then, Mexican environmentalists have gained protection of sites of great biological and ecological importance, such as the Tajamar mangrove in Cancún, Quintana Roo.

Before this progress, legal certainty to defend the environment was lacking, and the right to private property prevailed. This, together with other conditions, led to La Pona being gradually devastated, hectare by hectare, buried by rubble and degraded as a public space that was part of the area of the Ex Ejido Ojocaliente, from which hot springs flowed and which gave its name to the state: Aguascalientes.

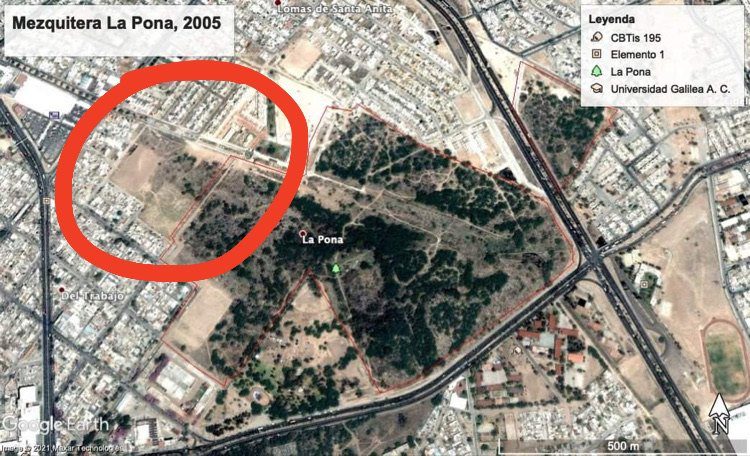

Navigating through Google Earth it can be seen that from 2007 to 2009 there was an important change in La Pona, since a substantial part was urbanized — a total of three hectares of what today we know as the Nueva Alameda subdivision. This is because, in 2007, the owners took legal action against the city council. They won because of a modification that the council had made to the land use designation with the intention of protecting it as an ecological preservation zone, after the 1999-2001 administration had given it a mixed housing designation.

In this context, SOS Mezquitera La Pona AC mobilized what became an endurance run for the mezquitera. It promoted different actions such as citizen consultations through the collection of signatures, participation in forums, in Citizen Councils, in social campaigns and media outreach, among others.

By 2010, this and other organizations collaborated with the state government in the preparation of the Preliminary Technical Justification Study, in a failed attempt to declare La Pona as a Municipal Protected Natural Area. On March 18 that year, they would be announcing in the media that the mezquitera had been established in a town hall meeting. However, on June 24, 2010, it was reported that the State Environment Institute (now the state Sustainability, Environment and Water Secretariat) informed activists that the municipality’s request for the declaration was inadmissible under the Urban Code.

Currently, the real estate industry insists on usurping the last remnants of the green belt, previously clearing them to obtain changes in land use designation — claiming in the environmental impact statements that they have no woodlands designation. The municipalities directly have the last word, as long as the citizens do not intervene.

Usually, land use changes are granted without taking into account the original designation, but in this case, the change had already been considered for the mesquite stand in the urban development plans.

Faced with the insistence of the real estate industry to develop the last mesquite stand, members of different government and civil society groups keep organizing, for example in the Reforestation of La Pona mobilization on Aug. 7, 2021.

The lesson learned is the imperative for the community to influence policy and planning on the permanence of native trees. Activating the collective memory refines the defense strategy by incorporating cultural values. The premise is essential: Native trees are adapted by evolutionary processes that have allowed them to survive the semi-desert climate of which they are part. They save us, but they also saved our ancestors and could save our descendants.

Sofía González-Ponce is the founder of the Salvemos La Pona collective. She has a degree in communication and information from the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes and is a teacher in social and humanistic research from the same university. She is an ecofeminist activist and a companion of people and processes for the defense of human rights.

This article was reported and written with the generous support of The One Foundation.

The pre-Hispanic cultures living in the deserts knew and venerated the properties of mesquite, so much so that they named it “the Tree of Life”. We have used all its parts for different purposes; it has been a primary source of food, fuel, shelter, weapons, various tools, fibers, dye, cosmetics, medicine, furniture, and fodder, among others.

- Defending Mesquite, the ‘Tree of Life’ - September 22, 2021