Despite a global pandemic endangering communities around the world, with the new global hotspot now focused in the US, the Trump Administration continues to rip up wildlife habitat to push forward border wall construction. This is endangering the rural communities that the wall is being built through, as workers pour into these communities to continue construction — communities that often have limited health resources to respond to this pandemic.

“It’s terrifying to see wall construction ramp up in the midst of this pandemic. The Trump administration is risking the lives of families, local business owners and construction workers for nothing but a racist campaign promise. He’s adding to the long, painful legacy of injustice against border communities, including Indigenous nations, who are disproportionately falling ill and dying from the virus,” says Laiken Jordahl, borderlands campaigner for the Center for Biological Diversity. “Imagine if the thousands of construction workers building the wall were instead building emergency hospitals, crisis centers and critical infrastructure to fight the pandemic. Imagine if the billions of military dollars stolen for Trump’s wall were pumped into responding to this crisis. We could save thousands of lives.

“If there was ever a time to realize the futility of Trump’s blind nationalism and relentless individualism, the time is now. We’re all in this together. Our fates are deeply entwined. Walls have never been the answer.”

As border wall construction rips through some of the most biologically diverse lands in North America, it endangers nearly 100 endangered species and threatens to destroy over two million acres of land, according to a 2017 Center for Biological Diversity study. Today, “all that area is still under threat. We’re watching some be destroyed and the study become a reality as hundreds of miles of walls are contracted,” says Laiken Jordahl, borderlands campaigner for the Center for Biological Diversity. “These projects are already happening.”

Jordahl’s work has spanned the entire border region, taking him across the borderlands to fight border wall construction in each state. “I think many people still don’t realize that the border wall — in addition to being a racist symbol of Trump’s hateful border policies — also will wipe some species off the face of the planet and have irreversible environmental impacts, changing these places forever.”

Garet Bleir spent 100 days last year living out of a tent beside the Carrizo/Comecrudo Nation and allies in the Indigenous villages near the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas. Read about it here.

The Trump Administration is planning to take over $7 billion in Pentagon funds this year toward wall construction to fund an additional 880 miles of new border barriers by the year 2022, walling off nearly the entire borderlands — for much of which the contracts have already been issued, says Jordahl. Approximately 650 miles of border barriers were already constructed before 2017, with the Trump Administration constructing around 110 miles of border wall in place of other designs or in areas where no barriers existed previously, and has already identified $11.1 billion to construct a total of 576 miles of wall, according to documents obtained from CBP. With the Administration’s release of a statement claiming they plan to construct at least 450 miles of border wall by the end of 2020, this year is a critical one for endangered species under threat of this construction. Some include the Saguaro cactus, Mexican gray wolf, jaguar, ocelot, and Peninsular bighorn sheep.

To some unfamiliar with the borderlands, when someone mentions the border, an image of a vast desert wasteland comes into mind. In reality, the borderlands of the US and Mexico are some of the most biologically diverse lands across North America.

While these lands and the endangered species living within them would normally be protected under federal and state regulations, the Trump administration has waived dozens of critical environmental safeguards along the border such as the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Clean Air Act in order to push through construction, uprooting critical habitat for endangered species along the way.

Saguaro Cacti: “Thousands of ancient Saguaros are being destroyed, chopped up like firewood, and discarded into trash heaps.”

—Laiken Jordahl

Despite the official narrative that the border wall is only replacing already existent barriers, Jordahl says this depiction falsely minimizes the destruction. “DHS is replacing tiny vehicle barriers — which wildlife and water could pass through with total ease — with a massive solid wall that will stop every single species of wildlife larger than a pocket mouse in its tracks,” says Jordahl. “Liberal pundits and politicians want to make it look like Trump isn’t delivering on the wall. But it’s insulting and a slap in the face to those of us who live on the border and are watching these walls go up, and is extremely misleading to the entire American public.”

Jordahl has witnessed firsthand this destruction in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, which is currently being razed in spite of its designated wilderness status. As 30 miles along the southern end of the park is bulldozed, “thousands of ancient Saguaros are being destroyed, chopped up like firewood, and discarded into trash heaps — all on sacred lands of the Tohono O’odham, who actively use the area for ceremonial purposes.” One site in the National Monument — Monument Hill, a sacred burial site of the Tohono O’odham — has already been blown up to make way for the border wall.

Under normal circumstances if someone were caught damaging or cutting down a Saguaro, a protected species, they could face felony charges and a 25-year prison sentence. But the Trump Administration is literally bulldozing thousands of them in a national monument. “We’re watching the destruction of a national treasure,” says Jordahl. “It’s heartbreaking.” Following bulldozing, a new 30-foot high wall is now being built.

Not only is this construction bulldozing protected flora, it also threatens desert aquifers and rare aquatic resources like Quitobaquito Springs within the national monument through what some environmental researchers and activists are calling reckless groundwater extraction by DHS for concrete mixing for the border wall.

Near Quitobaquito Springs, the desert is now being flattened next to the only habitat in the world of the Quitobaquito pumpfish and the Sonoyta mud turtle as DHS extracts water from the aquifer that feeds the springs. Approximately 300 miles east along the southern border of Arizona, similar rare aquatic resources at the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge are also in peril.

There, DHS is drilling into and drawing from aquifers that are the sources for contained aquatic habitats called cienegas. These unique alkaline wetlands systems are the home of four endangered species of Yaqui fish: the topminnow, catfish, slider, and chub, which live nowhere else in the US, says Jordahl. “We could see these habitats — the entire habitats for all of the Yaqui fish — wiped off the face of the map in the next year or number of months,” he adds. Jordahl has already received reports of declining water levels at the refuge.

“It’s so heartbreaking to see them sucking up this groundwater — a non-renewable resource in the desert…much of which dates back to the Ice Age…and which would never be allowed if it weren’t for the waiver of the Endangered Species Act,” he says. “Giant tanker trucks fill up at the wells all day long, taking out 112,000 gallons of water each shift.” Some estimates project at least 50 million gallons of water are being used over the course of construction. Elsewhere in southern Arizona such aquatic habitat has already been eradicated from agricultural development and irresponsible water usage, Jordahl adds, making this remaining habitat all the more important for protecting the dwindling remnants of these species and habitats.

“They don’t have to suck the entire aquifer dry to damage the springs,” he says. Just by dropping the water table by a foot or two, water flow to the springs may stop, destroying the cienegas, he says. This means death for not only the endangered species living within, but also puts the greater ecosystem in the area at peril as these water sources in the desert are critical for the endangered Chiricahua leopard frog, endangered northern Mexican garter snake, protected desert tortoises, as well as other mammals that drink from these pools and migratory birds that use the area on their migrations — some of which are also endangered.

Mexican Gray Wolf: “We are blocking off a chance for these animals to one day be a self-sustaining, healthy, recovered population.”

— Maggie Howell

A subspecies of the Gray Wolf, the Mexican Gray Wolf is the southernmost occurring gray wolf in North America, the smallest of its species — ranging from 50 to 80 pounds — and also the most endangered. Usually a combination of brown, gray, black and white, historically the predator ranged all across the borderlands into Northern Mexico and across the Southwestern US. Today, the core of the US population straddles the dividing line between New Mexico and Arizona, with many finding home in the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico. The species primarily dwells in mountain woodlands where they can find sufficient habitat and prey including deer, rabbits, and javelina, according to Maggie Howell, executive director of the Wolf Conservation Center of New York.

In the late 1970s, under a binational effort by the US and Mexico to save the dying species, seven surviving Mexican gray wolves were captured and bred in captivity. Today, all living Mexican gray wolves descend from these seven. As border wall construction pushes forward in New Mexico and Arizona, this wolf – one of the most endangered mammals in North America — is becoming walled off from the only other population of the species which dwells in Mexico, thus reducing the chances that the species may recover a healthy genetic diversity within its population.

The US population currently totals 131 while the population in Mexico is around 20 to 30, says Howell. As these respective subpopulations hold such little genetic diversity, it is imperative for their survival that as the subpopulations grow, they cross the US-Mexico border and breed with each other, according to a recovery plan established by a renowned group of scientists chosen by the USFWS for their expertise in wolf science.

While the population may be the largest since its reintroduction into the wild – making it more likely the subpopulations come into contact if they aren’t impeded by obstacles — it’s also the most inbred the species has been, says Howell. “And the larger it gets, the harder it will be to perform a genetic rescue to the wild population — which is basically all brothers and sisters now,” she adds.

Most recovery decisions of the subspecies center on genetic considerations, a critical way of measuring integrity and health of animal populations. “They might look healthy,” says Howell. “But if every animal is represented by the same genes, it could take one disease they are susceptible to, to threaten the entire project and to wipe out the entire population.”

In 2016 to 2017, conservationists’ dreams of uniting these two populations seemed imminent when a wolf from the Mexico subpopulation ventured across the border into the US where he remained for a few days before returning to Mexico. Just a year later a female wolf crossed the border as well. “What these wolves did — and these are just the wolves we know about — is proof there is hope to connect these two subpopulations,” says Howell.

But then came the border wall. “Now any wolves migrating north from Mexico or south from the US will find an impenetrable wall in their path,” says Jordahl. “They’ve already completed a huge amount of border wall in New Mexico and we’re seeing it cut off all possible migratory paths for the wolf there, save a few high elevation corridors in the boot heel.”

As of 2019, 317 Mexican gray wolves were living in the captive population, spread across 53 partnering organizations throughout the US and Mexico, says Howell. Her organization, the WCC, is one of the organizations participating in this species survival plan on the captive side.

“The fact that something everybody in the recovery of Mexican gray wolves is working towards, is now literally being blocked off…I’m feeling the devastation to this subspecies,” says Howell. “We are blocking off a chance for these animals to one day be a self-sustaining, healthy, recovered population.”

One of the strategies for slowly recovering the subspecies genetic pool and growing the subpopulations until they unite is a process known as cross-fostering. This is where researchers insert captive-born wolf pups into litters of wolf mothers in the wild with pups of similar age, says Howell. But as only two among 10 cross-fostered pups are known to have survived in 2016 and 2017, this is an additional strategy, but not a replacement for connecting the US and Mexico populations.

The wild and captive wolf pups need to be born just days apart and planted into the foster mother’s litter soon after birth, requiring extensive coordination between the USFWS monitoring wild wolves, and the captive breeding organizations. In the captive facilities, breeding pairs are meticulously chosen using inbreeding coefficients to find what pair is least related and could help augment the wild gene pool.

Within the first 18 hours of a new litter being born, the USFWS will be in contact about how many pups were born to see if the litter is large enough to transfer one from that mother to a foster mother in the wild. In 2019, 12 pups were set to be fostered in wild dens. Two were taken out of the wild and fostered by mothers in captivity so as to not overwhelm a mother with a large litter or if it could benefit the genetic pool by bringing the wild genetics back into captivity, says Howell.

On April 26, 2019, a Mexican gray wolf of the WCC birthed a litter of five pups. Their health was meticulously monitored to see if they could handle cross-country travel while still being defenseless with their eyes still shut and dependent on the mother.

A pilot donated his private plane to the effort to get the pup where it needed to go as quickly as possible, and “in the middle of the night, the USFWS did a quick health check on our litter and picked a robust little girl to be the traveler, then set off,” says Howell.

Upon landing, the team joined the interagency field team and together trudged with the pup in the rain through the mountains for hours to find the wild den they had previously surveyed. Upon arrival, they were surprised that the mother did not leave – an unusual occurrence as wolves are usually fearful of humans. Usually, when the mother leaves the den, this gives researchers time to insert the pup, cover it with dirt from the den so it smells like the others, and monitor the other wild pups. But on this rainy evening, the mother seemed to not want to leave.

Running out of time, the researchers located an opening in the side of the den where they saw the mother nursing her pups, “so they decided to drop our little pup through the skylight and hope that mom would embrace the pup and raise her as her own,” says Howell. The team looked on as the pup squirmed on top with all the other pups and immediately started nursing. “It was a really good sign and considered a successful mission.”

“This is one of the most important conservation efforts in the history of Mexican wolf recovery,” says Jim deVos, Assistant Director for Wildlife Management at the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

“We named her Hope, because we think she represents a hope of the Mexican gray wolf recovery,” says Howell. “How cool to think that we have this little New Yorker running around the wilds of the Southwest,” she adds, laughing.

Jaguar: Border wall construction slated for critical corridors

Elsewhere along the border roams the jaguar, a yellow and reddish-brown spotted big cat, that at nearly 300 pounds is the third largest cat in the world and the largest one native to North America. Jaguars are typically found all the way from the Brazilian Amazon through to their northernmost reaches of the Sky Islands of Arizona and New Mexico, where conservationists are working to restore the jaguar to its traditional territory. Endangered and protected in both the US and Mexico, one of the main jaguar recovery goals of the USFWS is to allow the species to roam between the two countries. At least seven jaguars have been documented in Arizona within the past twenty years – three of which have been seen in the past several years. But with border wall construction continuing through critical cross-border corridors for the species, this recovery will likely be upended.

Arizona canyons, riparian vegetation, and rivers crossing the border are used by jaguars within their distribution range, says Sergio Avila, a big cat wildlife biologist. It was in this type of habitat, including the Sky Islands in the Huachuca Mountains abutting the border, where El Jefe was famously photographed. El Jefe was the subject of the most publicized jaguar sighting in the US after being spotted between 2011 and 2016. There have been several other jaguar sightings just north of the border in the Sky Islands along the region of Nogales, and Avila himself has photographed jaguars about 35 miles southeast of Nogales on the southern side of the border.

“So all these little dots on the map, basically let you see that, One: jaguars are using the Sky Islands, Two: they’re moving back and forth across the border and, Three: any construction and any activities of law enforcement along that region of the border would definitely impact the movements of jaguars,” says Avila. Between Douglas and Nogales there are numerous jaguar sightings within the last 20 to 25 years. All those areas are now slated for border wall construction, with half of the border in that region already walled, notes Avila. “The border wall is not a problem that Trump started. The wall is a problem that we’ve been having for a long time and Trump has weaponized,” he adds.

Avila is quick to note that the impacts to Jaguar and other wildlife at the border go beyond the physical wall; but also all that comes with it — the trucks, construction materials, cranes, and machines used to build that wall; as well as the helicopters, roads, patrols, checkpoints, lights, and generators used in further militarization of the southern border. “Without ever getting to see the border wall, the jaguars would not use those areas anymore because of all the movement before, during, and after construction,” says Avila. “This all amounts to destruction of public lands and is happening in places that jaguars could use or have used.”

Avila, a wildlife biologist born in Mexico, had grown up always wanting to be a big cat biologist.

“I had the great pleasure of achieving my life dream, first studying mountain lions in the mid-’90s, and then studying jaguars in northern Mexico in 2003,” he says. His research has taken him to remote areas, working with other researchers and scientists studying to protect these cats. Their mission was to locate the northernmost breeding population of jaguars and connect them with jaguars recently spotted north of the border in the Sky Islands of Arizona — which put national attention on the species. Their work focused on identifying and connecting corridors between northern Mexico and southern Arizona for these jaguars – the same corridors now under threat of border wall construction.

In 2005 he began a new program reaching out to landowners in Mexico to help create research corridors where jaguars were moving from Sonora into Arizona. Avila trained numerous volunteers and students who wanted to support the project by looking for jaguar tracks and setting up remote cameras. “And so that way we expanded the reach of the project in a safe way,” he says.

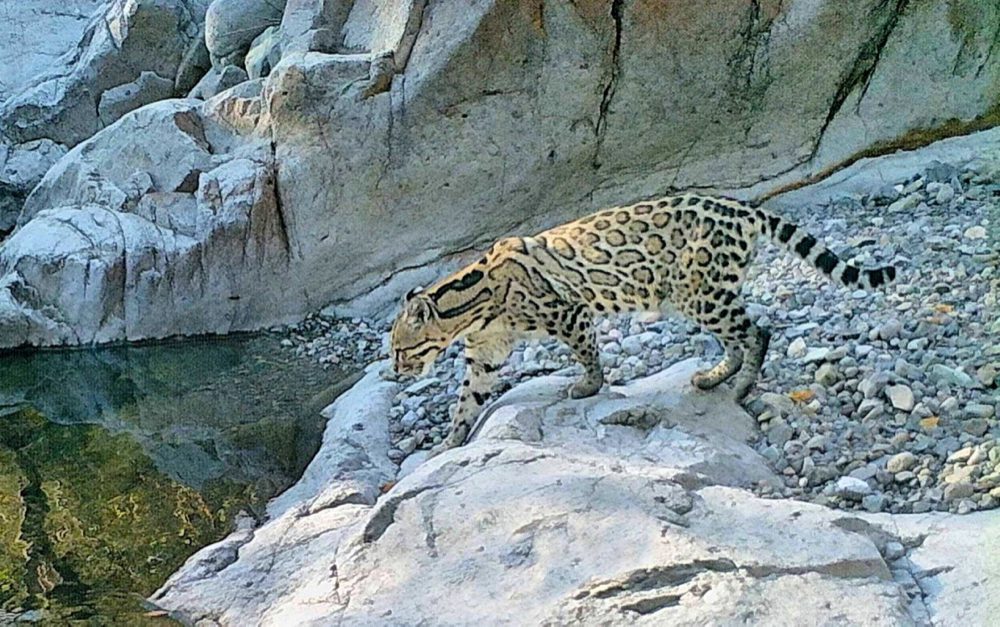

In 2006, Avila identified a jaguar corridor at El Aribabi ranch, setting six remote cameras which in 2010 and 2011 identified two new jaguars in the area. But as it turned out, in just the first month of looking for big cats using remote cameras, they ended up photographing another protected species entirely: the Ocelot.

The Ocelot: “This is a death sentence”

— Sergio Avila

The Taumpalipan thorn scrub of the Rio Grande Valley is the native habitat of the Ocelot in Texas — cinnamon-colored nocturnal cats spotted and streaked in black and weighing around 30 pounds, which are currently recovering with just 50 left in their Texas population. However, making this recovery increasingly difficult is the fact that less than one percent of the species’ native habitat is still intact within South Texas, and border wall construction threatens to destroy even more. As border wall construction continues through the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge — a connection of nearly 150 wildlife refuge tracts connecting isolated pockets of wildlife in the valley — the opportunities for the Ocelot in Texas to connect and breed with the sub populations in Mexico are becoming slimmer.

This endangers one of the main recovery plans in diversifying the genetic pool. “This is a death sentence because they have nowhere to go,” says Avila. “They have no connections, no genetic inter-breeding, and will be impacted by habitat destruction.”

In addition to Texas, five Ocelot have now been spotted in Arizona since 2009, which researchers believe came from a population located just south of the border in northern Sonora. This is the location where Avila and his team were granted permission by a private ranch owner to set up cameras on his land in Mexico to photograph jaguar. Within a month, what came back on the cameras was the ocelot.

This “made the rancher’s heart melt”, recalls Avila. “It made him commit directly to conservation. He expressed his love for this species and in that moment he saw the photograph, he said ‘I’m going to remove all the cattle I have in that Canyon, because from now on this canyon will be the Canyon of the Ocelot.’” The ranch was eventually designated as a protected national area in Mexico.

What the team discovered was a small breeding population of ocelots just over 30 miles south of the Arizona border at Rancho El Aribabi, now a 25,000-acre conservation, cattle, and ecotourism ranch in the Sky Island Region, says Jim Rorobaugh, lead researcher of the resulting study published in late January. The ranch is located in rugged and mountainous terrain, ranging from Sonoran desert scrub through desert grassland, mesquite and oak savanna, and into pine-oak woodland up in the highest elevations, he notes. The team identified 18 different ocelots over eight years. Most importantly, the team documented photos of kittens, proving that they had both males and females. This showed that not only were there ocelots in the area but that these cats were a viable breeding population — the northernmost wild breeding population of ocelot. This means the population could likely move into Arizona and create a population contributing to recovery there, says Rorobaugh.

This research led to a critical addition to the recovery plan for ocelots, which was updated in 2016. The original plan did not consider the Arizona Sonoran subpopulation of ocelot, but solely Texas subpopulations.

But, just last year DHS planned a 26-mile noncontiguous stretch of border wall just north of the ranch, according to documents released by the Sierra Club, before the plans were put on hold due to insufficient funds, according to documents obtained from the Center for Biological Diversity from their lawsuit against the Trump Administration. With Trump recently securing $7 billion in funds from the Pentagon for border wall construction this year, it is unclear if these plans will be put back into action.

Protected core habitats, open space like the conservation ranches provided in Mexico, accessible clean surface water, and habitat connectivity between habitat and populations are all necessities for ocelot to persist in the borderlands, says another wildlife biologist who conducted the study, Jessica Moreno. “All of these things are threatened or stopped entirely by having a physical barrier inhibiting them from making those movements,” says Moreno.

In addition to the physical wall itself comes roads and border patrol traffic, lighting, noise, and air pollution. “All of these things combined create impacts far beyond the physical footprint of the wall,” says Moreno. “Ocelots are very sensitive to those kinds of disturbances, so they would not even try to cross. So a wall hampers all of our investments in protecting land on both sides for the recovery of the ocelot in Arizona.”

“They seem to be persisting despite us so far and we do still have ocelot in Arizona. I find that to be very hopeful,” says Moreno. “But we have to step up our recovery to help these animals do what they’re naturally attempting to do — survive and thrive here.”

Peninsular Bighorn Sheep: The Necessity of Cross-Habitat Connectivity

Inhabiting dry and rocky desert slopes, canyons and washes ranging from the San Jacinto and Santa Rosa mountains of California all the way south of the border in Baja California, Mexico, the already endangered Peninsular bighorn sheep finds itself under renewed threat from a combination of border wall construction and other development along vital bighorn sheep corridor in the borderlands, according to the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. This development threatens to further fragment habitat connectivity and isolate the remnants of the species from each other. In California, a stretch of wall being built through the Yuha desert is encroaching on corridors where the sheep migrate across the border on a frequent basis, says Jordahl.

The Institute is conducting ongoing research exploring cross-border connectivity between populations, with its 2012 population survey showing a much larger population of bighorns just south of the border than had been expected. Through this work, researchers are working on detailing the most critical corridor and habitat for the sheep.

Over the past two centuries, peninsular bighorn sheep have suffered from habitat loss, disease, and overhunting, bringing their populations under 276 in the 1990s, leading to their listing as a federally endangered species in 1998. While the population has since rebounded in the US and is recovering south of the border, careful management of the species is needed to continue the recovery. “We’re at a stage where there are around 800 peninsular bighorn [in the US] and that’s been a slow process getting back,” says Jim DeForge executive director of the Bighorn Institute. “That number has been going up and down.”

A cross-border collaborative study in 2015 between the Institute and the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Mexico, published new findings on connectivity amongst various populations of peninsular bighorns. This connectivity across landscapes — in this case across the man-made divisions of the US-Mexico border — is vital for a population such as this one to flourish, according to the study, for both genetic diversity and reoccupation of traditional territory.

The study provides a warning that limiting connectivity between populations can increase their extinction risk. The study determined that to date, despite recovering from a near eradication, the species has retained a “substantial genetic variation,” but that border wall construction or further development along the border “could have severe consequences” on the demographics, connectivity, and genetic diversity amongst the population, including subjecting the population that straddles the border to an increased risk of local extinction. In a species that has already been nearly brought to extinction from disease, maintaining this healthy genetic diversity becomes all the more important to resisting disease that could wipe out the population.

One organization that has seen the effects of peninsular bighorn sheep vulnerability to disease firsthand is the Bighorn Institute. In the ’80s and ’90s the species was being wiped out by a bacterial pneumonia which was killing up to 90 percent of the lambs before reaching two to three months of age; a level of death that continued for around a decade, says DeForge. During this period, the Bighorn Institute brought in sick and dying lambs and started to rehabilitate them. Over time their efforts grew into a captive breeding and augmentation program which over the years has allowed the organization to release 127 bighorn sheep back into the Peninsular ranges. “It’s prevented two populations of Peninsular bighorn from disappearing,” says DeForge. Their efforts in the San Jacinto mountains brought the female population from four to now 41, he adds, and succeeded in a similar recovery in the Santa Rosas.

“We’re losing our liberties; we’re losing our freedom. We’re losing our democracy. For some of us, people of color, that means our lives are at risk too. We need to hold our representatives accountable to reject the waiver of laws for construction at the border. Congressman Grijalva of Arizona has introduced a bill to reject this waiver several times in Congress, and we need people to ask their representatives to support this initiative to restore the rule of law along the border. Everybody needs to push the representatives to restore these laws. This is not only a problem for border states, this is a problem for the whole country.“

— Wildlife biologist Sergio Avila

Garet Bleir (they/them) is a Sierra editorial fellow and award-winning investigative reporter, documentarian, and photographer covering environmental justice, energy, Indigenous rights, and the borderlands. Their work has been published by Netflix, ZDF, Yahoo News, Center for Public Integrity, Intercontinental Cry, and Indian Country Today. You can follow their work on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

A different version of this story appeared in Sierra Magazine.

- Video Series: Juneteenth Voices Demand Change - June 19, 2020

- Border Wall Plows Through, Despite Pandemic - April 17, 2020

- ‘There is no safety. There is no family. There is no home.’ - November 6, 2019

Bighorn Institute border wall Center for Biological Diversity endangered species jaguar Mexican gray wolf ocelot peninsular bighorn sheep Wolf Conservation Center