We’re in an outbreak currently. But I don’t mean the COVID pandemic. It turns out that outbreak has a second definition: it means when populations grow dramatically large, beyond their carrying capacities. As David Quammen details in his book Spillover, disease outbreaks can be considered “as a subset” in this broader category.

In Spillover, Quammen goes into detail about one outbreak—that of tent caterpillars—and how, inevitably, it is controlled by a virus that literally melts them from the inside. These viruses are then eaten by other caterpillars as they chomp away, dissolving them over time, and spreading more virons on the leaves future caterpillars will eat. Eventually, in a dense outbreak of caterpillars, the virus wipes out much, if not all of the population.

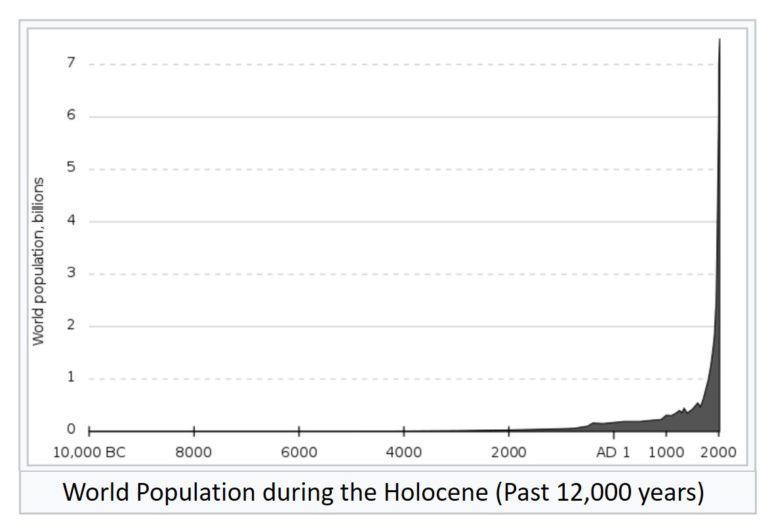

Quammen makes the case that humans, too, are in outbreak (not that a case really needs to be made), citing: our huge numbers (8 billion and heading to 10 billion*); our dense cities; our mobility; our continuing expansion into forests and wild ecosystems; our large and dense populations of livestock; our misuse of antibiotics, especially on said livestock populations; and climate change (spreading disease vectors’ ranges). And he says it with pizazz: “We provide an irresistible opportunity for enterprising microbes by the ubiquity and abundance of our human bodies.” (That feels like it should be on a corporate recruiting poster. “Ask about our signing bonus!”)

But he also makes the essential point that humans cannot be separated from the natural world—or more accurately, he notes, “There is no ‘natural world’….There is only the world. Humankind is part of that world, as are ebolaviruses, as are influenzas and the HIVs…, as are chimpanzees and bats…, as is the next murderous virus—the one we haven’t detected yet.” (Did I mention Quammen wrote Spillover in 2012?)

That’s a key point. Viruses are part of the Gaian whole. Indeed, they are a primary means of stabilizing overgrown populations. This is not a mystical statement, or some suggestion that Gaia has sent us a plague. As Quammen notes, “evolution seizes opportunity.” When there’s a big, connected, genetically similar population, viruses, bacteria, and other disease vectors view this as an all-you-can-eat buffet, if they can just figure out how to get into the restaurant.

Human Behaviors and the Spread of Viruses

And in our case, humans have pretty much thrown open the door. As Quammen points out several times, the effects of a pandemic depend on whether we act ‘diligently or doltishly,’ and concludes the book with one epidemiologist (the tent caterpillar expert) saying that unlike caterpillars, we’re smart. We have a lot of ‘heterogeneity’ [variety] in our behavior and we can make many choices to limit infection and impede its spread. Quammen even includes a long list of behavioral modifications from not sharing needles and avoiding unprotected sex to not eating bushmeat and not penning pigs beneath mango trees.

And yet.

Spillover, of course, was written before COVID, and we are proving again and again that we are not as smart as we could be. In fact, we’re doing deeply stupid things—like not wearing masks. Or traveling for Thanksgiving. Or going to gyms and restaurants. I cannot process this with a rational mind. Instead I wonder, whether, as with certain species of grasshoppers, do outbreak dynamics lead us to behave differently?

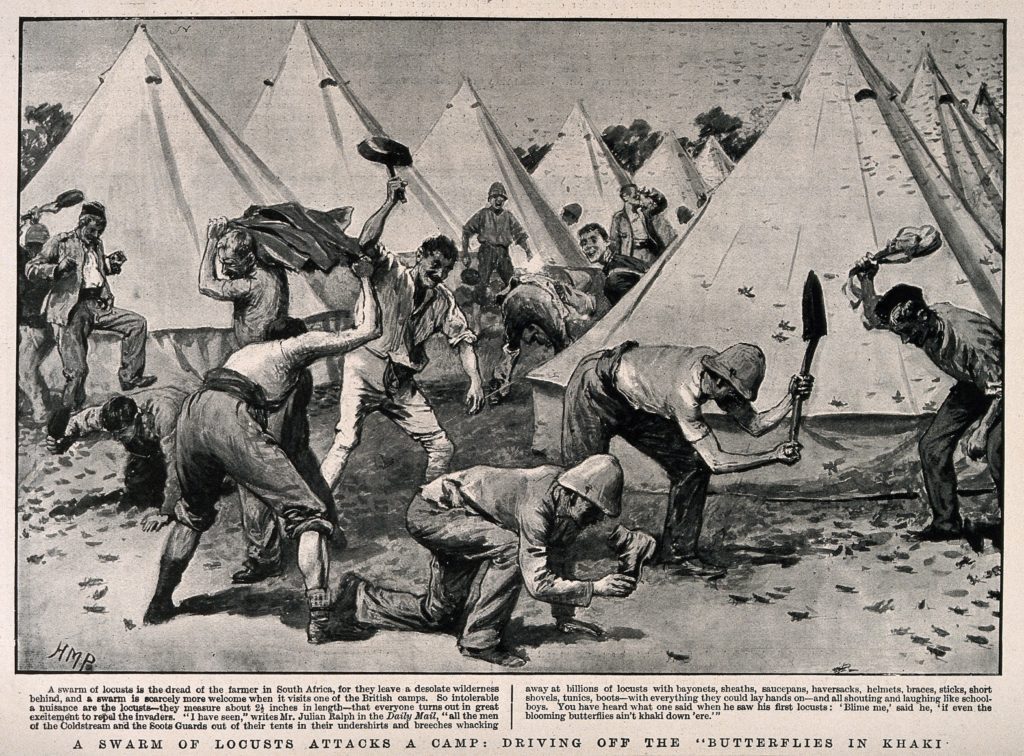

Grasshoppers are an interesting example of how, during outbreaks, they undergo a dramatic transformation. They become locusts—changing colors, growing wings, and swarming. Research found a while back that they swarm both to eat, and to not be eaten, as locusts will eat the locusts in front of them (hence they’re always trying to nibble at the one in front and avoid the one behind).

While horrific, this collective behavior helps to stabilize their population. Why this way instead of a virus? Perhaps being so mobile, viruses can’t keep up? Perhaps the evolution of this self-correcting mechanism made those subspecies of grasshopper (not all swarm) adapted better—a mechanism to prevent a complete and total devastation of their environment, a fail-safe, so that there would be future generations of grasshoppers to continue on.

Have we, too, changed our behavior in our current outbreak? Specifically in ways that will reduce our total population?

Before I can attempt to answer that, I feel I first have to answer several other questions.

First: when did we hit outbreak levels? The 1500s? When we spread across a continent and started gobbling up North and South America (like an invasive species)? The 1800s when industrialization opened up the floodgates for population growth? The last 75 years, during the post-World-War II period of globalization and modern medicine? In the next 50 years when we peak at around 10 billion people and much of our environment has been despoiled or stripped bare?

These are all heightening levels of outbreak. At what stage did behaviors start changing, if they did? Do and will behaviors change further as outbreaks intensify? (Grasshoppers don’t turn into locust until they hit a specific level of population density, and before that they play a healthy and important role in the ecosystems of which they’re part.** In that case when did we turn to a swarm or have we yet to?)

Or maybe it’s simply that there’s a third variable clouding the data. Perhaps the glut of energy and food—or the cultural evolution that allowed us to tap fossil energy and build our entire world from it—has enabled us to swarm, to follow our impulses (or more correctly the advertisers’/influencers’ impulses) to go anywhere, consume anything, all in the name of experience, freedom, novelty. And our new hyperconnectivity spreads both diseases and bad ideas (such as social media and news channels having conflated the simple idea of wearing a mask with being a political statement).

But ultimately, we’re a cultural animal. In our species, culture keeps overconsumption in check, or drives us to swarm. “Get to the mall for Black Friday specials—bodily harm be damned!” “Cruise around the world to see its wonders, even as you destroy it in the process…” We want, almost need, to believe everything is fine. We would expend too much brain energy doing otherwise as living in a state of cognitive dissonance is exhausting.*** And hence, we delude ourselves into thinking that recycling will save the day. Or renewables. Or other technologies just over the horizon. Or Earth’s resilience (though Earth’s resilience says nothing for whether we’ll be part of the new Earth order).

So perhaps it’s simply easier to swarm, scrambling from one social media post to the next email, to the next work assignment, to the next. So that there’s no time to think about the hoard of other locusts chomping at our tails (or the storms, the fires, the floods, and the other horrors just behind them). Just don’t look behind you! Keep moving forward! The promised land is just ahead!

Ironically, it was our outbreak that led to this swarm and behavioral changes. And I’m not sure there’s a way to unswarm a swarm, other than the obvious one.**** And perhaps that explains why so many people refuse to believe COVID is real, that novelty and ‘freedom’ are more important than safety and shared responsibility. Because pandemics are self-correcting mechanisms, exploiting our own behaviors to facilitate this. But I hope not. People, unlike caterpillars, can control their behaviors—at least in theory.

One silver lining, though. Unlike with tent caterpillar outbreaks, which end very badly for the caterpillars, as locust populations get smaller (though “substantially” smaller than the number that triggered their swarm) grasshoppers do move back from being a raving hoard to a beneficial part of the ecosystem again. Perhaps, after our numbers go back down (way back down) we too will resume our healthy place in the Gaian system.*****

&&&

*Will COVID will even show up on long-term population growth curves? Keep in mind that about 60 million people die each year, while 140 million are born. If a vaccine is indeed effective and is rolled out in 2021 ending the COVID pandemic, COVID will have caused around 2-4 million deaths over 2 years. The biggest population growth impact of the pandemic will probably be in family-start delays. But even then, the blip will be minor compared to the annual increases of 80 million people/year and probably won’t affect long-term population projections.

**Humans did too. Grasshoppers stimulate plant growth and cycle nutrients. There is ample evidence that Indigenous peoples improved certain plants and entire ecosystems with their active management—a good example of humans not in outbreak.

***A quick search did not turn up any research that specifically studied whether cognitive dissonance burned more calories, but it’s a strong hypothesis. Thinking burns more calories and wrestling with difficult thoughts is thinking. We work actively to either align behavior with thinking or thinking with behavior to alleviate cognitive dissonance, most likely to get to a calmer, less tumultuous (and less energy-intensive) mental state. This might actually be an underlying mechanism to explaining swarm behavior. Easier to swarm along with the group than to think through an alternative—and risk being eaten while you stop and contemplate that alterative.

****The obvious one being population reductions. Ideally that’ll come from intentional degrowth: choosing to have smaller families, later rather than sooner, and choosing to adopt more. But if we fail to make that choice, then increased death rates becomes the default option.

*****Bonus questions for the avid reader: In grasshoppers, the shift from their “solitary” to “gregarious” stage (locusts) is actually triggered by increases in serotonin levels. Could our shift from Native to Invasive, from Indigenous to Gregarious have also been triggered by shifts in brain chemistry? Could crowding have triggered serotonin increases and led us to metaphorically swarm? To, unlike Buddhist monks, be unable to feel oneness with the world any longer? Can people exit the swarm by shifting their brain chemistry? And as with Buddhist monks who have changed their own brain patterns, can meditation help in this process? As one researcher of this phenomenon noted, “we can all take responsibility for our brains.” Perhaps even to a degree that we can help end our swarm stage.

&&&

Interested in reading more on Spillover, without reading the book? This great essay in Emergence Magazine is a good place to start.

Erik Assadourian is a sustainability researcher and writer, adjunct professor, game designer, homeschooling father, and Gaian.

This story was originally posted at www.gaianism.org

- The Parable of the Humane Philanthropist - January 24, 2023

- Should climate denial be illegal? - August 17, 2021

- Should we all just ‘lie flat?’ - July 13, 2021