FT. YATES, North Dakota — Tribal leaders and constituents across Lakota Territory and elsewhere welcomed a hard-won court order on July 6 to shut off the oil flow in the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) within 30 days.

“Today is a historic day for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the many people who have supported us in the fight against the pipeline,” said Mike Faith, chair of the tribe headquartered at Ft. Yates. “This pipeline should have never been built here. We told them that from the beginning.”

His tribe, followed by the Cheyenne River, Yankton, and Oglala Sioux tribes, sued the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for breaking federal laws and glossing over the devastating consequences of a potential oil spill in the Missouri River’s Oahe Reservoir when permitting the pipeline crossing upstream from drinking water supply intakes here in 2016.

Chair Harold Frazier of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe applauded the decision of U.S. District of Columbia Judge James Boasberg “in finding what we knew all along, that this pipeline, like many other actions taken by the U.S. government, is in fact illegally operating.”

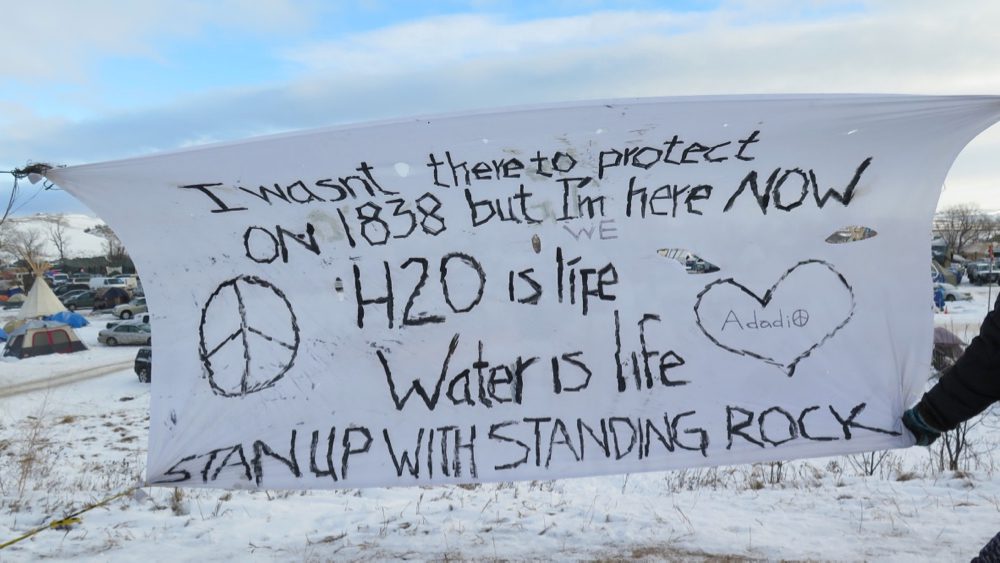

Frazier recalled the world-renowned 2016-2017 mass mobilization against the pipeline in which grassroots resisters and leaders of all Seven Council Fires of the Great Sioux Nation, or Oceti Sakowin, established camps at Standing Rock to support of the tribal governments’ lawsuits.

“It has been six years since the Dakota Access Pipeline began slithering a path through our treaty territory,” he said. “In 2016 water protectors stood up to the dangers that have threatened this land of which we are all a part. Today, the U.S. District Court ordered that the snake of oil moving through our territory cease….”

Similarly, the Yankton Sioux Tribe said it “has been standing shoulder-to-shoulder alongside its Dakota and Lakota relatives, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Oglala Sioux Tribe, and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, to defend and protect the treaty rights, historical and current subsistence land uses, and cultural and spiritual connections with the land that the Corps and Dakota Access imperiled by approving, constructing, and operating the crude oil pipeline, which carves through the tribes’ 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty territory.”

Yankton Sioux Tribal Vice-Chair Jason Cooke said, “I would like to recognize our water protectors that stood watch at the camp on the banks of the Missouri River with water protectors from many other tribal nations. Their sacrifice, hard work, and prayers paved the way for today’s decision.”

The Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association (GPTCA), the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), and the National Congress of American Indians Fund (NCAI Fund) stressed, “The decision ensures that the treaty-reserved rights of the plaintiff tribes – the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, the Yankton Sioux Tribe, and the Oglala Sioux Tribe – are adequately addressed, along with any other land and natural resource considerations, in a full-fledged and well-documented environmental review process.”

GPTCA, NARF, and NCAI Fund, which took part in submitting an amicus brief in the latest proceedings in the case, said they are “encouraged by this outcome,” adding, “We hope that this decision helps pave the way for full and proper environmental impact studies as well as meaningful consultation with tribal nations that have direct or indirect stewardship over the lands under review.

“Our organizations will continue to work to ensure that every time tribal lands and resources are at stake, the environmental review processes meet all legal standards and respect the federal government’s trust obligations to tribes set forth in federal laws,” they wrote.

Boasberg ordered the shutdown to last at least until a proper consultation with tribes and an environmental impact statement with public participation are completed, as required by the National Environmental Protection Act, NEPA. The process has an estimated duration of at least three years.

That means “It may be up to a new administration to make final permitting decisions,” said Earthjustice, a law firm that represented plaintiffs.

Boasberg ordered the Corps to re-examine the risks of the pipeline and prepare a full environmental impact statement on March 25 but left open the question of stopping the flow and draining the conduit until now.

“Fearing severe environmental consequences, American Indian tribes on nearby reservations have sought for several years to invalidate federal permits allowing the Dakota Access Pipeline to carry oil under the lake,” the judge said. “Today they finally achieve that goal — at least for the time being.”

The Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe’s lead litigation counsel Nicole Ducheneaux, an enrolled member of the tribe, said she is “100 percent satisfied with the way it all turned out.” However, she added, “Don’t get it twisted, it’s not over. There’s a big fight yet left.”

An environmental impact statement usually leads to permitting, and other pipeline construction projects loom in Indian country.

Dakota Access LLC, representing pipeline parent company Energy Transfer Partners, intervened on the side of the Corps of Engineers, arguing a shutdown would “pose an existential threat to DAPL” due to “massive” revenue loss. It said DAPL could lose as much as $643 million in the second half of 2020 and $1.4 billion in 2021 if the oil flow is halted.

“There is no viable pipeline alternative for transporting the 570,000 barrels of Bakken crude that DAPL is capable of carrying each day,” and railroads do not have the capacity “to fill the breach,” Dakota Access LLC states.

The company was in the process of applying for a permit to double the volume permitted on the line when the court order came down.

The court “does not take lightly the serious effects that a DAPL shutdown could have for many states, companies, and workers,” it states. “Losing jobs and revenue, particularly in a highly uncertain economic environment, is no small burden. Ultimately, however, these effects do not tip the scales,” it says.

“When it comes to NEPA, it is better to ask for permission than forgiveness,” in Boasberg’s opinion, which notes: “If you can build first and consider environmental consequences later, NEPA’s action-forcing purpose loses its bite.”

The ruling adds that Dakota Access LLC arguments strictly emphasize “its own interests and those of the industry…The seriousness of the Corps’ deficiencies outweighs the negative effects of halting the oil flow,” Boasberg concluded.

Chair Frazier responded, “The fact that this operation had been operating illegally for three years before this conclusion was finally made shows you the power that money holds on the American government.

“It is time to put people before profit and seriously consider the impact of not only this project but the harm that this project brings to our land and planet.”

Frazier recognized the importance of grassroots support that thousands of people gave the tribal government lawsuits. “It is with extreme gratitude that I acknowledge the work, sacrifice and perseverance of every water protector involved in this fight,” he said.

“We must never give up in our struggles and need to follow the examples that our past naca (chiefs) and leaders have given us. We need to unite and continue to protect our way of life for the future of our people.”

Concluding a written statement datelined at his Eagle Butte headquarters, the chairman signed off with the Lakota rallying cry carried since the standoff at Standing Rock: “Mni wiconi! (Water is life!)”

Cheyenne River Sioux tribal member Joye Braun, an organizer for Indigenous Environmental Network who was among the first resistance supporters at the camps inaugurated on April 1, 2016, rejoiced with the same rallying cry.

“This is your win, water protectors!” she said. “I couldn’t be any more proud of every single one of you!” She counseled to “Enjoy the win!” and warned that other pipelines, such as the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline, will be shut down, too.

An elder of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and founder of Sacred Stone Camp, which Braun helped establish and anchor, LaDonna Brave Bull told Democracy Now!: “You ever have a dream, a dream that comes true? That is what it is.”

Sicangu Lakota water protector Cheryl Angel, also a Sacred Stone Camp leader, remarked, “Finally! Justice prevailed.

In point of fact, the victory was one of a superfecta of four wins in early summer 2020 for water protectors opposing oil pipelines.

A judge temporarily closed down the aging pipes of Enbridge Line 5 that lie exposed in the water at the bottom of the Great Lakes where they cross the ecologically sensitive Straits of Mackinac in Michigan. The line belongs to Enbridge Inc., which caused the Superfund cleanup after its Kalamazoo River 2010 tar-sands crude leak, the nation’s largest-ever land-based oil spill.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Montana U.S. District Court order to halt the Keystone XL Pipeline construction on the grounds that its Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP12) water crossing permit violates the Endangered Species Act. The stay will be in effect until the U.S. Circuit Court rules on the pipeline company’s appeal.

While other pipeline companies are not barred from using their NWP12s, the ruling threw ice water on some of the most heated pipeline building controversies around the country.

Dominion Energy and Duke Energy Corp. immediately announced the cancelation of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline buildout “due to ongoing delays and increasing cost uncertainty which threaten the economic viability of the project.”

With the knowledge that the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court already has deemed an appeal is not likely to be successful in the Keystone XL Pipeline case, the would-be builders of the line in North Carolina and Virginia decided to cut their losses and run.

“This announcement reflects the increasing legal uncertainty that overhangs large-scale energy and industrial infrastructure development in the United States,” said a joint statement from Thomas F. Farrell, II, Dominion Energy chairman, president, and CEO, and Lynn J. Good, Duke Energy Corp. chair, president, and CEO.

This is an updated version of an article in the Native Sun News Today by Health & Environment Editor and Esperanza Project collaborator Talli Nauman.

- Clemency for Lakota icon Leonard Peltier called ‘moral indictment’ - January 21, 2025

- Lakota tribes, grassroots close ranks to defend Black Hills watersheds - January 21, 2024

- Native ‘hempsters’ follow global cooperative example - August 30, 2023