“Superheroes don’t wear capes. They wear ponchos and sombreros.” The phrase is often repeated in the Andean highlands. And now as they see their lands and their culture under increasing threat, the Indigenous people of Ecuador are employing that phrase once again, as they go out into the streets in the face of danger, as they have many times during their history.

Alan Adams, a former Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador who has rekindled his Andean friendships in retirement, has been working with Mushuk Yuyay, a local community development organization in the Indigenous Kañari homelands. Now back home in New Jersey, he has been monitoring the headlines and social media feeds anxiously as violent protests rack the country’s capital. Meanwhile his friend Nicolás Pichazaca, a community leader from the indigenous Andean Kañari community, makes his way along with a human tide coming down from the high mountains and up from the jungles to make their voices heard.

Here is Alan’s take on what’s happening in Ecuador and why.

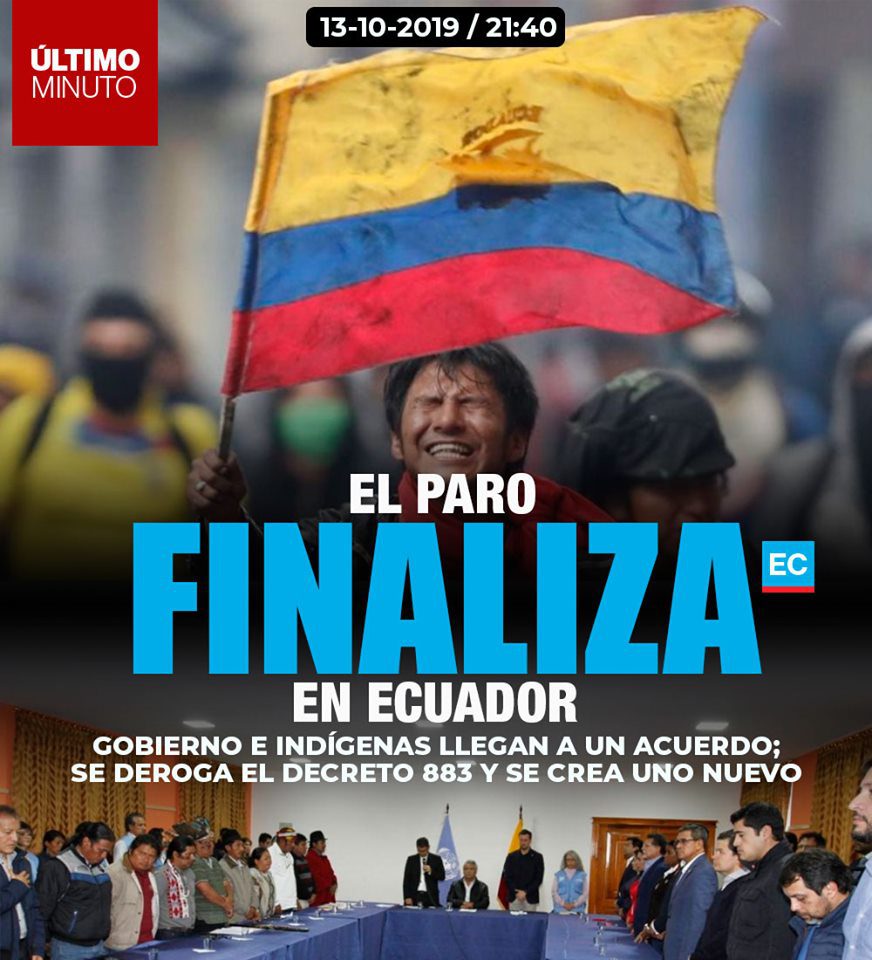

UPDATE: At publication time, the Kañari caravan was in Quito joining the throng of demonstrators in a victory celebration: The Moreno government agreed to rescind the austerity decree and has promised to rewrite it with input from the people. Nicolás Pichazaca wrote me: “Our work and strategy have not been in vain, not only for the Indigenous people, but for all Ecuadorians. It is one more story.”

María Mercedez Guaman, president of the Quilloac Cooperative, said:

“We have won the repeal of the decree with the blood of our brothers.”

Victory, but ever vigilant. And now some background on the Kañari participation in the current uprising.

High in the Andes of southern Ecuador live the Kañari people, who have been struggling for their freedom, for Sumak Kawsay, a good life, for thousands of years. Their present challenge comes at the hands of the President of the Republic who made a pact with the International Monetary Fund and expects the poor of Ecuador to pay. When Lenín Moreno Garcés took office, the Kañari people were cautious, hopeful, and patient because he promised to break with the extractive policies of his predecessor, Rafael Correa. He humbled himself before Indigenous people in a solemn ceremony where he accepted the blessing of the many nations that comprise the State of Ecuador.

Slowly it became obvious that the winds in Quito had shifted, and the President began to move in a different direction. I often describe Lenín Moreno in Shakespeare’s words, “Commanded always by the greater gust…” The greater gust these days was coming from the IMF, which demanded austerity, and Moreno decided to find cash by removing fuel price supports that had been in place since 1970. Fuel prices shot up by a dollar a gallon. That is enough to wipe out the budgets of most small businesses as well as of most families. In addition to the gas prices going up, the IMF is requesting an increase in fees for all government services and for utilities, a new value-added tax, a consumption tax, and an increase in the ceiling on interest rates so that banks can charge whatever interest rates they want.

Immediately, the Kañari people responded with peaceful, but vocal, demonstrations throughout their communities. They joined in support of labor unions and other groups, but mostly in collaboration with other indigenous communities and organizations of Ecuador. They blocked roads and joined the general strike. They requested dialogue with the government. Violence began to erupt in the protests — which some, in civilian as well as governmental sectors, suspect is being incited by infiltrators paid by Correa. President Moreno declared a State of Emergency to quell the violence. This only increased the people’s determination to find a solution that would benefit all and lead toward a more secure future for the country.

President Moreno responded that the austerity policies would not be changed. He said that the demonstrations did not originate with the people but were encouraged by the former president of Ecuador, Rafael Correa, working with President Maduro of Venezuela. The statement only fanned the flames of resistance. However, there is evidence that Correa and other actors are taking advantage of the situation to sow doubt and suspicion. The Indigenous organizations need to weave through this confusion cautiously to keep the issues in focus.

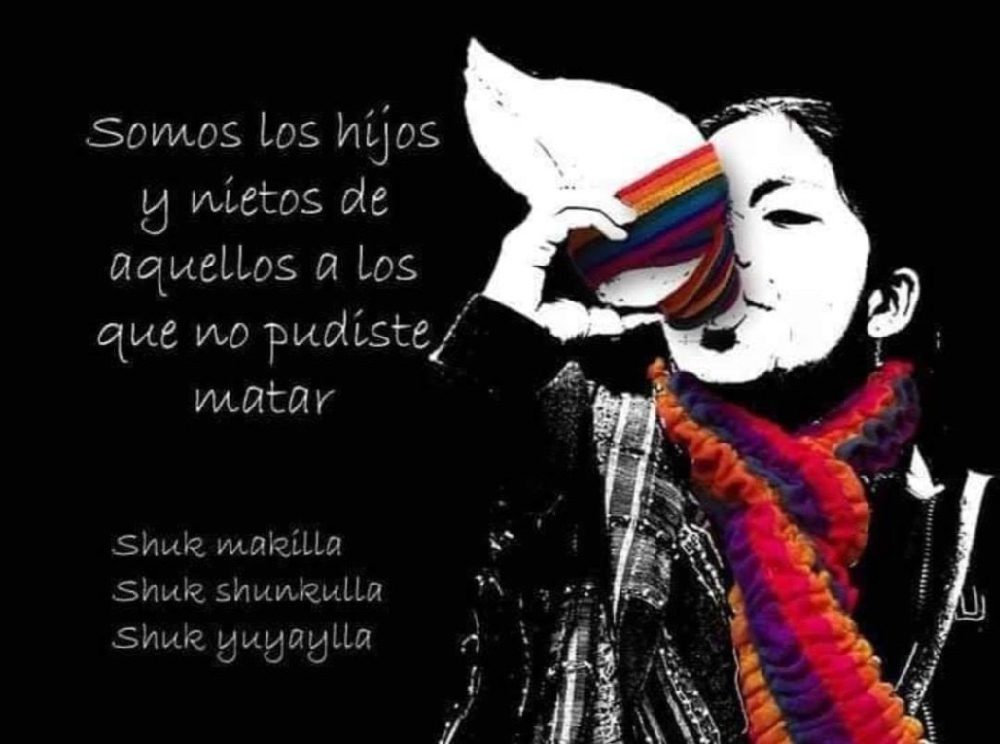

Disrespect is not new for the Kañari people after centuries of being used as beasts of burden, as the Kañari poet José Buñay put it years ago. But they are determined not to go back to the abuses of the hacienda days. Last week, as the protests continued to escalate and began to grow violent, Moreno took his government from the capital of Quito to the coastal city of Guayaquil. When the demonstrators set out to meet him there, the mayor of that city stated bluntly that “Indians” are not welcome in her city. They should go back to the páramos, the high mountain grasslands.

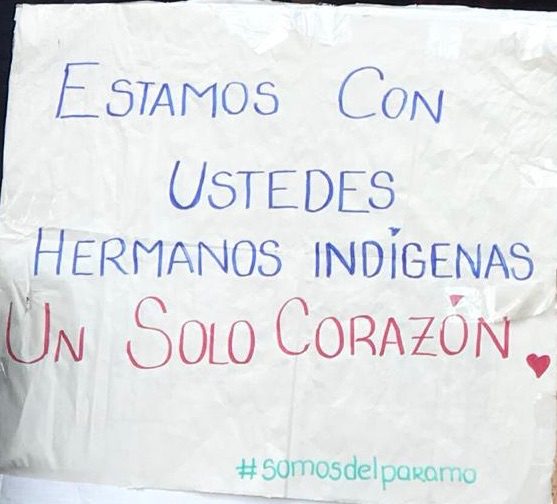

But Kañaris will not be humiliated. Indigenous people don’t take abuse lightly. A movement was launched to withhold food from the Indigenous mountain farms to Guayaquil. Several Indigenous people posted photos of their páramo homes with pride. They also posted the reminder that Indigenous peoples can be found in the universities, the professions, government offices, elected positions, and everywhere in Ecuadorian society. They even live in Guayaquil.

The President of the Republic did not distance himself from the mayor’s racist statements, but stood with her.

The declarations that I read over and over again from Kañari friends are not that the price of gas should go down, but that neoliberal policies must end. The IMF must go. What they are demanding is a complex set of changes, each affecting the other, that cannot be oversimplified, that the Kañari and all Indigenous peoples of Ecuador are laying out. There is no simple fix. They are proposing a comprehensive solution on the other side of the insults and accusations that will insure that a way toward a peaceful and lasting social and economic system can be secured. This solution will be sought by large numbers of determined and united people.

Faced with this necessity, the people of the Kañari communities, both those in Ecuador and those who have emigrated, decided to add their voices. Truckloads of people departed. They made laughing videos of people climbing aboard moving overcrowded vehicles. Wave after wave of men, women, and children declared their determination to protect their rights as Ecuadorian citizens.

The last to leave departed Mushuk Yuyay and the United Cañari Cooperatives (UPCCC) on Saturday morning. It was not lost on anyone that this was Columbus Day, the day set aside to commemorate the beginning of the struggle that they have been involved in for over 500 years. They drove slowly over roads that had been blocked and made contacts with others along the way. On Saturday evening, the caravan announced that they had Puruhua People in their company now. They are the Indigenous Nation to the north of the Kañari in the province of Chimborazo. On Sunday they set off again in trucks, cars, buses, and on foot on a cold and cloudy day.

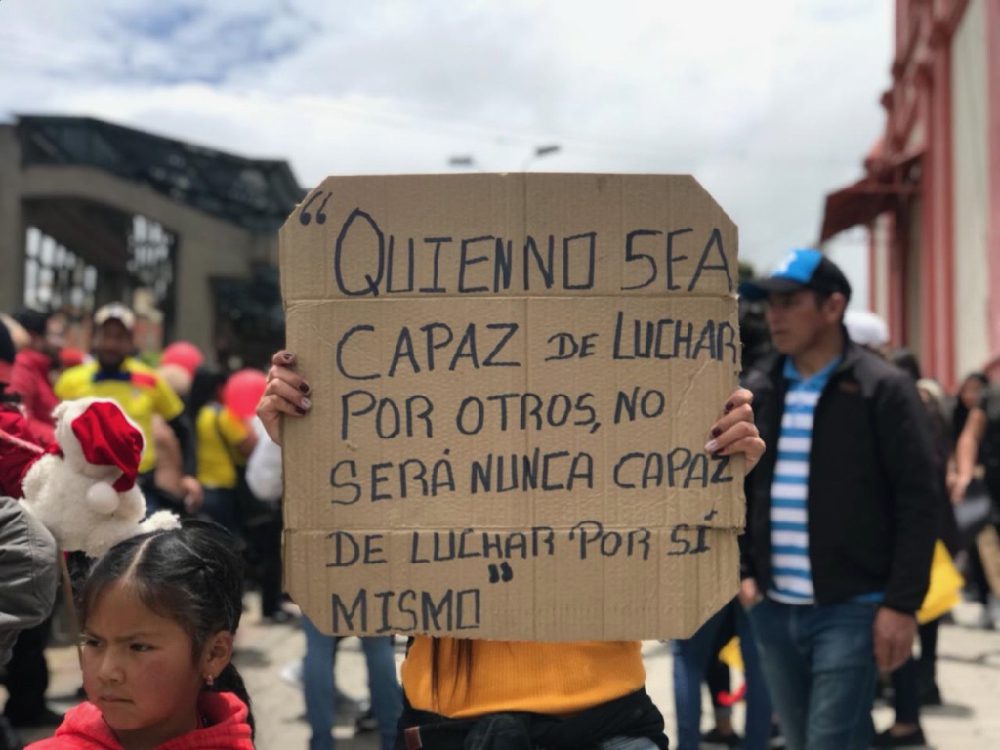

The plan was to arrive in Quito in time to lend force to the words of the leaders of the Indigenous organizations in a meeting with the President. They wanted to show the strength of a united people and to prove that hardship and danger will not deter them. If they were afraid of hardship and danger, they would have remained on the haciendas instead of securing their freedom under the agrarian reform during the 60s. We remember, too, that over the recent Ecuadorian history, Indigenous demonstrations have led to changes of government and policy changes. This one promises to be just as effective. What sets this demonstration apart is its spontaneity and comprehensiveness. The people responded immediately to a threat with thought and care in order to find a solution consistent with their goals. To get elected Moreno said and did some things he seems to have forgotten, but the people didn’t forget.

This is one more chapter in the history of the people who developed their science and art over the millennia, resisted the Inca, survived the haciendas, rebuilt their lives through the Agrarian Reform, ended the agrochemical-based Green Revolution, confronted (and continue to confront) Climate Change, and now are dedicated to helping to redesign the social and economic institutions of Ecuador. The significance of this continuing struggle cannot be overemphasized.

Alan Adams is a former Peace Corps Volunteer currently collaborating as a volunteer consultant for Mushuk Yuyay, a community development organization in the Ecuatorian Andes. Stay tuned for his next piece: Lino’s Dream, a personal story.

“Those who are not capable of fighting for others, will never be able to fight for themselves.”

“Turn off the television, turn on the mind!!”

“For our fallen heroes, not of the cape but of the poncho and sombrero”

- A Historic First: Indigenous Kañari to Host World Quinua Congress in Ecuador - February 11, 2025

- Heathy Children, Healthy Future in Ecuador - December 9, 2019

- Lino’s Dream - October 28, 2019

Congratulations to the Indigenous people of Canar for their fearless determination to advocate for their rights and way of life in a peaceful manner. Alan Adams walks beside them in spirit and pride.

Very amazing that the Indigenous people of Ecuador were able to stand up to the powerful people in government and the IMF to force a more fair compromise. Thank you Al for posting!

I congratulate Alan for his fine reporting on a complicated story, always with his never-ending solidarity with the people of Cañar. Thanks Alan!

Animo!!!