One day in July 2017, Marianna Treviño-Wright was driving her car by the levee that crosses the private property of the National Butterfly Center. Then she saw something unsettling. Surrounded by the dense Texas thornscrub that grows on either side of the levee, she pulled over, got out of her car and confronted five government contractors outfitted in safety vests, hats, goggles, and chainsaw pants.

Marianna, the Executive Director of this unique butterfly conservatory which doubles as the largest native plant nursery in the United States, remembers the moment clearly. She recalls how three of the men were operating chainsaws as another drove a brush hog while the final worker was on a boom-mount brush cutter – a machine used to quickly clear the land of trees. Marianna was horrified. Years of habitat restoration and development at the center were being destroyed before her eyes.

This article is part of an ongoing series by journalist Garet Bleir and our partner publication Intercontinental Cry investigating the humanitarian and environmental devastation caused by the border wall sweeping through South Texas. For this story, Garet spent nearly a month living in a tent on the grounds of the National Butterfly Center with the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas and allies who are defending their homelands from border wall construction. All photos by Garet Bleir. Republished with permission.

“Our entire community, our health, our inheritance, and our future are being thrown under the bus for Trump’s project simply designed to reward political allies, campaign and cronies,” reflected Marianna, who has now fought for two years to prevent this nature preserve from being turned to mulch. “We’ve been sold out.”

An estimated $3.7 billion in funding is being used to support the “top border barrier priorities” for the U.S. Border Patrol, currently concentrated in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas, according to documents obtained from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The agency has increased the number of agents on the ground, as well as technology and air support, as according to CBP, these sections of the southern border have the most migrant presence.

The National Butterfly Center is just one piece of a conservation corridor that has been painstakingly pieced together over many years through one of the nation’s most biodiverse regions — and it is in the path of the border wall along with tens of thousands of acres of critical wildlife refuges beyond the butterfly center. These areas serve to conserve dwindling native habitat in the Rio Grande Valley for endangered species and future generations. Construction of the border wall has already begun to turn much of this critical habitat into mulch.

The wall that is planned to slice through the National Butterfly Center is an 18-foot vertical barricade of concrete rising from the base of the existing earthen levee, topped with 18-foot steel bollards – 36 feet in all. A fall of over 30 feet often causes life-threatening injuries or death, leading Marianna to refer to the border wall as a “wall of death” for those trying to cross over it. “It is also a wall of death for wildlife, destroying hundreds of square miles of the United States for this project,” she says.

Marianna’s encounter with the crew of government contractors occurred more than nine months before any congressional appropriation for border wall construction was approved in the area, but followed Trump’s Executive Order 13767, which demanded a contiguous border wall to be constructed on the U.S.-Mexico Border. No one had given the center legally required prior notice, negotiations, or legal action, and the center had not granted permission for these actions. Marianna approached them, asking them what was happening. She recalls the Tikigaq Construction company workers and their crew leader, Peter Sydow, telling her they had been sent by the government to clear the trees and brush along an approximately one-mile section of road from the levee to the Rio Grande, ahead of the border wall.

Since that time, Marianna has been a vocal advocate against the border wall and what she feels are violations of constitutionally protected rights in the United States by Border Patrol and the Department of Homeland Security.

A Tawny Emperor on the grounds of the National Butterfly Center.

Tawny Emperors are not commonly found in areas inhabited by humans.

Director of Operations Max Muñoz was equally appalled by the news. “I’ve worked so hard for so many years to be able to continue this wildlife corridor that we’ve been trying to create, and all of that is going to be taken away,” says Muñoz. “A lot of power and sweat has been put into creating this center, the wetlands, classrooms, and a place for children to be able to study in a natural environment. All this and these many years of research and work need to stay here and be passed on to the future. They can’t take something that we protected for so long.”

The CBP refutes the allegations that they were altering this landscape illegally. In a statement to IC, the agency claimed to be “performing routine maintenance which included the trimming of brush/trees on a patrol road located within the NBC property.”

Since 2017, the nearly $4 billion that Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and CBP have received for just over approximately 200 miles of new border barriers have come from a combination of appropriations along with the Treasury Forfeiture Fund, according to documents obtained from CBP. In Fiscal Year 2019, the project received an additional $2.5 billion in reprogrammed funds from the Department of Defense, but this action was blocked by a court ruling in late June. The Trump Administration has since asked the Supreme Court to overturn the ruling.

To date, approximately 50 miles of new border barriers in place of older designs have been completed using funds appropriated for DHS – constituting around seven percent of the existing southern border wall and two percent of the U.S.-Mexico border as a whole.

OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL BUTTERFLY CENTER AND IMMEDIATE THREAT

The National Butterfly Center, located in Mission, Texas, within the Lower Rio Grande Valley on the U.S.-Mexico Border, is a 100-acre wildlife center. The four-county region of the Lower Rio Grande Valley is one of the mostbiologically diverse areas in North America, with 11 biologically distinct ecosystems, each harboring their own unique plant and animal species. Out of over 700 butterflies who find their home in the United States, nearly 40 percentof those can be found in the three counties at the southern tip of Texas – with over 200 of these species found in the National Butterfly Center alone.

The center is a project created by the North American Butterfly Association (NABA), a 4,500-member non-profit organization with 30 chapters sprawled across the U.S. The organization is dedicated not only to the study of native butterfly species, but also to their conservation, both goals of which are exemplified through the National Butterfly Center. The goal of the center is to help educate the public while providing refuge to hundreds of wildlife and plant species native to the Rio Grande Valley. The center also serves as an important resource for future generations and the local community with field trips bringing in close to 6,000 students per year, from preschoolers to college-age students.

Despite the international importance of these conservation efforts in a time of climate catastrophe, the National Butterfly Center is currently fighting border wall construction that is expected to bulldoze nearly five acres of habitat in the center alone – in addition to turning nearby wildlife refuges into mulch. If the proposed border wall is allowed to go through the center’s property, it will effectively put 70 percent of the center’s land on the southern side of the wall, cutting off access from animals trapped on the other side as well as impacting access for staff and visitors.

Amongst the habitat destroyed in this construction would be host plants for pollinator species, feeding and breeding areas for local wildlife and lands set aside to conserve endangered and threatened species that find refuge in the center such as the Texas tortoise, Texas indigo snake, the Texas horned toad, and the Texan ocelot, as well as the gray hawk and nearly 500 species of birds that call the four counties of the Lower Rio Grande Valley home — 18 of which are listed as federally threatened or endangered. The birds in the region of Deep South Texas are the most diverse avian population north of the Mexican border. This includes species of birds and butterflies that migrate north or south through this wildlife corridor, such as the monarch butterfly’s famed mass migrations through the Rio Grande Valley each winter.

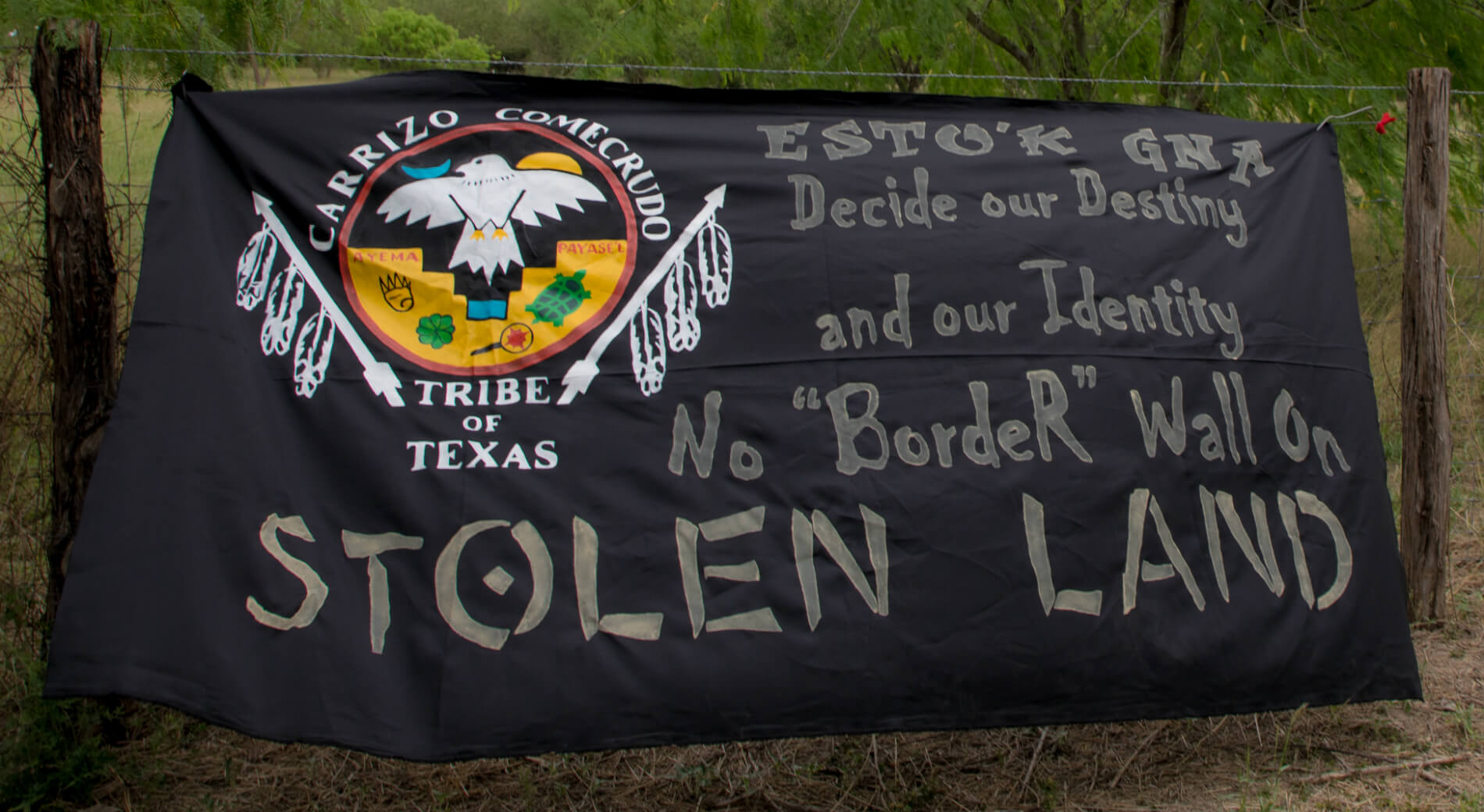

In response to this proposed destruction, which has already ravaged nearby wildlife refuges, the National Butterfly Center and NABA launched a lawsuit, which in its first attempt was summarily dismissed without a single hearing. They also joined forces with the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas – one of the peoples indigenous to South Texas — along with environmental organizations, U.S. military veterans and a strong coalition of activists and allies from the local Rio Grande Valley community to push back against the proposed construction and to protect their lands and the species living within it.

While many who are not familiar with the area envision the borderlands as a desert wasteland, the US-Mexico borderlands as a whole contain some of the most biologically diverse regions in North America. Stretching from San Diego, Calif., to Brownsville, Texas, there is a diverse patchwork of wildlife habitats from the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts to the subtropical, semi-arid and densely forested Tamaulipan thorn scrub in the Rio Grande Valley along its namesake river. The Rio Grande Valley, in particular, holds 11 distinct ecosystems, defying the singular image that many outsiders think of when envisioning the borderlands.

But despite the pockets of vibrant ecosystems, the Rio Grande Valley has suffered from generations of habitat destruction. Since the 1930s, 95 percent of the native habitat in the Lower Rio Grande Valley has been destroyed by the advent of rapid agricultural growth and urban development – trading in native biodiversity for monocultures as far as the eye can see.

It is the surviving but dwindling five percent of native habitat that is under threat or currently being destroyed by border wall construction. By waiving 28 federal laws, the federal government has already begun border wall construction nearby in South Texas as it rips through the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge – a set of 147 connected wildlife refuge tracts totaling over 90,000 acres intended to unite isolated pockets of wildlife trapped in the dwindling fragments of native habitat in the valley. This construction plans to further destroy the remaining five percent of native riparian, floodplain, and wetland habitats remaining, with construction expected to impact over 13,000 acres of wildlife refuge tracts in Hidalgo and Starr counties alone, says Laiken Jordahl, a borderlands campaigner with the Center for Biological Diversity.

DIVERSITY OF THE AREA

Until recently, the land of the National Butterfly Center was among the vast swaths of farmland in the Valley. It was only in the last two decades that the center was restored into an area containing the original biodiversity that once thrived here. About 18 years ago the lands were used as a commercial onion field. After the center purchased the property — chosen for its position on the southern tip of Texas, which allowed for one of the closest points to a tropical location while still sitting in the U.S. – they spent the next two decades slowly transitioning this landscape back into the native vegetation and biodiversity, attracting back the native species of butterflies and birds that were meant to thrive in the area.

Max Muñoz, originally a volunteer for the center, has been directly working on this transition for the past ten years. “Over so many years of work we’ve transformed the area completely into a native resource where you can find close to 300 native plants,” he says. The center has created an area that attracts an incredible diversity of wildlife while still being an accessible area for people to enjoy walking through, he adds.

WAIVING 28 LAWS

As Trump’s border wall nears completion in nearby wildlife refuges, the worries of the National Butterfly Center are mounting. These lands would normally be protected under various federal regulations and safeguards intended to save these areas from environmental and humanitarian destruction; however, critical environmental laws like the Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, and Clean Air Act have been waived by the federal government in order to push through construction in the area. Former Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen has evoked powers given under Section 102(c) of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 as amended by the REAL ID Act of 2005 to waive all laws that interfere with the fast and efficient construction of barriers in the interest of national security. In this way Nielsen waived 28 federal environmental, public health, and humanitarian laws.

“It seems like a strange sort of hodgepodge of laws that they’ve grouped together for waiver until you realize that the government is aware of all of the violations they intend to commit and is waiving the laws related to those egregious acts,” says Marianna.

Due to this waiver and without proper environmental surveys or community input, border wall construction happens completely outside the scope of these federal regulations, resulting in neither the government nor the populace knowing the full ramifications of construction.

Normally, anytime the federal government undertakes an action that is expected to significantly affect the environment, they have to go through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), meaning an exhaustive survey must analyze the impacts of those actions, often through environmental assessments and environmental impact statements. But this law has been entirely waived and so the impacts of this wall on endangered species, flow of water, and habitat connectivity have been neglected, says Jordahl. “Essentially Border Patrol has refused to even talk with conservationists or community members here and they’ve completely shut us out of the planning process. CBP has never held a public meeting or hearing to educate residents and concerned folks, or responded to the extremely detailed and time-consuming comments that we at the Center for Biological Diversity sent in for their response almost a year ago. There has been zero communication and all of our concerns remain unanswered.”

LAWSUIT

On Aug. 1, 2017, in a meeting following the initial destruction on the National Butterfly Center property, the former chief of the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector Manuel Padilla arrived with posters showing border wall design. He told Marianna that the crews would be back, and the contractors would return with a “green uniform presence,” recalls Marianna. “I asked him about that.‘You mean armed federal agents on private property to safeguard for-profit contractors?’ And he said, ‘Well, landowners tend to get pretty upset when we exercise eminent domain to take their land.’”

In an audio clip from the meeting, you can hear Padilla state, in reference to the locked gates on National Butterfly Center private property: “We cut locks all over the place. As long as we’re within 25 miles of that river, no one is going to stop us.”

Since then what he said has been true, says Marianna. “Every time a government contractor — whether that’s the appraiser or the archaeological surveyors or the environmental surveyors — has come there has been at least one, if not sometimes three or four armed border patrol agents accompanying those for-profit corporate employees.”

In response to this destruction, on Dec. 11, 2017, the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Border Patrol, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the CBP Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector.

The lawsuit claims that DHS had acted unconstitutionally – violating the Fourth Amendment by entering the property without either warrant or consent, and the Fifth Amendment by denying the organization’s right to due process. Regarding the Fourth Amendment complaint, the judge stated that the amendment gives little protection on unenclosed land located near one of the country’s borders and dismissed the Fifth Amendment complaint saying it was premature to bring the lawsuit before NABA sought compensation in the form of damages. The judge also validated the authority of DHS to waive 28 federal laws for border wall construction as Congress has granted the Secretary of DHS the authority to “waive all legal requirements’ that, in the ‘Secretary’s sole discretion, [are] necessary to ensure expeditious construction of the barriers and roads’ described in the statute.”

The Center has since filed an appeal. “We do hope one day to have our day in court,” says Marianna. “But in the meantime we continue to educate the public about the impacts of the wall; for private property owners, for immigration and national security, for wildlife, and for the environment.”

FUNDING THE WALL

Approximately 25 miles of new border and levee wall are planned for the RGV Sector using FY 2018 funding, with construction activities for approximately 13 miles of new levee wall system in Hidalgo County, home of the National Butterfly Center. Construction activities have already begun for most of the 13 mile section, according to documents obtained from CBP.

The $1.6 billion that was originally appropriated to build the border wall through the National Butterfly Center came from the March 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act, along with other security measures along the U.S.-Mexico Border — this was nine months after Marianna first encountered the workmen cutting down brush and trees on the center’s property. For the National Butterfly Center, some respite came in February in the FY 2019 appropriations package: U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas) and others managed to secure carve-outs from construction for five areas in the Rio Grande Valley: the National Butterfly Center, Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, La Lomita Chapel, and the Vista del Mar Ranch tract of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge intended to house a commercial spaceport for SpaceX.

“This is a big win for the Rio Grande Valley,” said Congressman Cuellar in a press release. “I worked hard to include this language because protecting these ecologically sensitive areas and ensuring local communities have a say in determining the solutions that work for them is critical. I know we can secure the border in a much more effective way, and at a fraction of the cost, by utilizing advanced technology and increasing the agents and properly equipping them on the border.”

This prevented the funds appropriated in 2018 from being used to fund construction at these locations; however, the future remains uncertain as the proposed budget only funds the government through September.

While reports have been mixed on what exactly this means for the safety of these lands, Marianna wants to make clear that the funds have not saved the center from border wall construction but merely “clawed back” the 2018 dollars put toward the wall. The 2018 appropriation for building the border wall at the National Butterfly center cannot be used for construction at the center, but what it did not do is spare the center from any future allocations, appropriations, or any money taken under the state of emergency declared by President Trump from other budget areas for building the border wall.

“It wasn’t a salvation so much as a temporary stay of execution,” says Marianna. “So we don’t feel safe at all. It is something that the government did to take the wind from beneath our wings to try to shut us up and make it so that we didn’t have any reason to speak out, but we saw through that.”

Fiscal Year 2019 funding, ending in September of this year, also included $1.976 billion dollars for approximately 85 miles of border wall in the Rio Grande Valley Sector. On May 28, 2019 and June 26, 2019, United States Army Corps of Engineers were awarded the first and second contracts respectively to construct a new bollard wall system within the Rio Grande Valley in Starr County, with construction anticipated to begin as early as November 2019, according to documents obtained from CBP.

In May of this year, the Pentagon shifted $1.5 billion from the Department of Defense into border wall funding, in addition to the $1 billion already shifted from the DOD to the border wall in March – both sources of funds identified by Trump under the national emergency declaration. This $2.5 billion dollars in wall funding was intended for use on six wall projects in New Mexico, Arizona, and California to block claimed “drug smuggling corridors” and construct around 129 miles of new border barriers, according to documents obtained from CBP. On June 28 of this year, a judge for the U.S. District Court for Northern California ruled that the Trump administration cannot use these reprogrammed funds to construct a border wall – ruling in favor of the American Civil Liberties Union in a lawsuit filed on behalf of the Sierra Club and the Southern Border Communities Coalition (SBCC) against the president’s use of emergency powers.

“We applaud the court’s decision to protect our Constitution, communities, and the environment today,” said Gloria Smith, managing attorney at the Sierra Club. “We’ve seen the damage that the ever-expanding border wall has inflicted on communities and the environment for decades. Walls divide neighborhoods, worsen dangerous flooding, destroy lands and wildlife, and waste resources that should instead be used on the infrastructure these communities truly need.” The Trump Administration has since asked the Supreme Court to overturn this court order.

While this is a huge victory for resistors to the border wall, the government has yet to take legal action against an additional $3.7 billion the Trump Administration has identified in military construction projects.

“Any of that funding honestly could be aimed at us and go toward construction contracts executed to build the wall through the National Butterfly Center, the La Lomita Historical Park, Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge and the site of a SpaceX Space Launch Facility,” Marianna says. Additionally, every year the government goes through a budgeting process, which the last two years has resulted in gridlock over border wall funding while using government shutdowns and the threat of them as tools to leverage power. This will happen again in just a couple months with the budget negotiations for 2020 already taking place, with a new fiscal budget arriving by the end of September this year.

“We fully expect that 2020 funding may be appropriated for the border wall here, making the 2019 bill irrelevant — or it could be state of emergency dollars that are used here,” she adds.

This wasn’t the first time that they’ve had trouble with government presence in the center. The National Butterfly Center has watched as over time the Border Patrol heightened its patrols – by SUV, ATV, dirt bike, horse, boat, drone, helicopter, and on foot, says Marianna. “They drag tires and alter the landscape, which kicks up dust and disrupts our regular business operations; they drive across the property while off-roading over our plants and sprinkler heads; they interrupt our events and activities while alarming visitors; they plant motion sensors on our property; they have planted video cameras on our property; and now have unlawfully brought civilian contractors onto our property,” she adds.

CBP did not respond to repeated requests for comment on the organization disrupting the center with their patrols.

The Border Patrol has authority for warrantless entry to private property anywhere within 25 miles of the border by virtue of the Immigration and Nationality Act. This could be in San Francisco, New Orleans, or even Manhattan – the Northern, Eastern, Western, and Southern borders are all under this law. While many think that CBP’s policies don’t affect them or encroach on their rights, they are also unaware that within 100 miles of any external border CBP is granted additional ability to function outside of the Constitution to conduct search and seizure without warrant. Roughly two-thirds of the U.S. population is located within 100 miles of an external border.

At the butterfly center, staff maintain that the government presence has led to harassment. Muñoz has seen visitors and members of the center told by Border Patrol they couldn’t be on Butterfly Center property.

“They had no right to tell them not to be here. This is our property, this is our center,” says Muñoz. “I live about a quarter of a mile away. I can’t drive past one of the Border Patrol agents without them staring at me. I have seen my color of skin is what triggers them, because I’ve been with people of lighter color and they don’t ask them any questions — I get asked the questions, I get surrounded, I get pulled to the side from a group. It’s discrimination.

“I have been working here for almost 10 years,” says Muñoz. “When I first started working here, it was great. Our Border Patrol liaison would come in and have breakfast and lunch with us and we had really great conversations together. If I would be driving away from the river, they would come up to me and say, hey, how did your day go?”

Since then, things have changed. About a year ago, Muñoz brought his daughters, wearing their school uniforms, to the butterfly center. They drove down to the river looking for seeds in their large F-250 pickup truck. Muñoz recalls as a Border Patrol agent in a vehicle spotted him and started driving after him. Muñoz stopped but the Border Patrol agent’s vehicle wasn’t big enough to get to Muñoz so he went another way and stopped in front of Muñoz.

“He came up to me really upset,” recalls Muñoz. “I assume he was frustrated because he couldn’t get through to where I was at first. He told me, ‘I need your ID. And I need to talk to those two girls.’ ‘Those two girls are minors,’ replied Muñoz. “‘They’re my daughters, you have no rights to talk to them, and I don’t give them permission to talk to you.’ Then he tells me ‘I don’t care what you think. I need to see an ID and I need to talk to them.’”

Border Patrol has access to the National Butterfly Center’s employee roster, vehicle makes, models, colors and plates. The agency even sent someone to photograph the employees’ personal vehicles at one point.

“I gave him my ID. He could’ve just taken it and looked me up in the system because back then Border Patrol had a picture of my truck, license plates, and a picture of me with my ID in their system to let them know that I work here,” says Muñoz. “Yet he didn’t take his time to do that. He wanted to get to my daughters. That’s when it kind of freaked me out to think that they want to impose these laws that are not there, just to get their way.

“When he noticed that I wasn’t going to budge, he called in six border patrolmen. Then they came in with a helicopter on top of me,” he adds.

CBP did not respond to request for comment.

“I was raised by a farmer who believed in respecting your elders, respect your president, respect the police officer, respect the uniformed man,” says Muñoz.

Muñoz’ father taught him, if you’re ever in trouble, look for someone in a uniform because that is your help. “If you’re in trouble with your own rights, there are people who can help you, and the government will never let anybody hurt you. So that’s what I used to tell my children: ‘If you’re ever out there, if you need any help, you go to the first person you see with a uniform.’

“This has changed my ways of thinking from ‘These guys are here to help us’ to the point where I don’t even bring my children to the river here, because you never know how Border Patrol is going to act,” he adds. “And to see the government waiving laws to get things done their way, and not caring about the community’s thoughts, really changes my perspective.”

Muñoz’ sentiments have been echoed by others amongst the National Butterfly Center staff as well.

“I think that most of us are more afraid of those with a badge than of any man, woman, or child that might stumble across the border or swim across the river lost, scared, and dehydrated,” says Marianna. “Those people aren’t a threat to us. They’re not a threat to America. They’re certainly not a threat to our values or our lifestyle or our jobs.

“The complete disregard for the Constitution, the disappearance of a remnant of native habitat, the waiver of laws — all of these things are now woven together,” Marianna says. “They’re connected to the degradation of our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and health.”

FLOODING

“We’ve seen the disastrous impacts that these barriers have had on communities and on wildlife,” says Laiken Jordahl of the Center for Biological Diversity. Of the nearly 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border, around 700 miles of border barriers have already been constructed – including the more than 50 miles of existing border walls in the Rio Grande Valley and another 100 miles of approved barriers, some currently under construction.

The Center for Biological Diversity itself has filed seven different lawsuits that challenge the border wall and other elements of border militarization that impact conservation, endangered species, public health and environmental justice. The Tucson, Arizona-based nonprofit is also collaborating with people on the ground, including Indigenous peoples, scientists, and landowners in these areas in order to push back against border wall construction.

Residents of the RGV have seen these lethal effects on wildlife firsthand when the Valley flooded in July of 2010 from Hurricane Alex. During that flooding, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reported to CBP that along sections of wildlife refuge tracts with border barriers, they found hundreds of shells of Texas tortoises – a threatened and protected species – that had been caught between the floodwaters between the Rio Grande and the border wall and drowned as a result. If the wall had not been there, the animals would have been pushed over the levee and into the floodplain. “Similar flooding could happen every few years,” says Jordahl. “So we’re really creating a death trap for the wildlife that’s left between the river and the wall.”

During that very same flooding, Muñoz,watched as the absence of border wall at the center saved the lives of species living in and around the area. “I was up there on the levee on the day that we had eight feet of water on the south side of the levee and I was able to see all these animals crawl over the levee – coyotes, bobcats, javelinas, snakes, even tarantulas; I saw them all cross over,” says Muñoz. The water at the butterfly center crested at the top of the levee at around 18 feet deep. “If you built a wall there, these animals are not going to be able to climb that wall,” he adds.

It isn’t only land-dwelling species that are threatened by the wall. While some may assume that the butterflies and over 400 species of birds that can be found in the area could just fly over the wall, that is not the case. The proposed 36-foot vertical wall in the center will prove to be an insurmountable barrier for various butterfly and bird species such as the Ferruginous Pygmy Owl that only flies about six feet in the air, as well as some species of butterflies at the center that fly no higher than about four feet.

While billions of dollars in funding have already been approved for border wall construction in the Rio Grande Valley, Jordahl remains hopeful that it will be stopped. “We really do believe that if we create this groundswell grassroots movement, there will be enough pressure to force DHS to stop their actions and to cancel some of these contracts. We have to keep fighting because places like this are too special to lose.”

BEYOND THE NATIONAL BUTTERFLY CENTER

The National Butterfly Center connects with 147 wildlife refuge tracts making up the Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge. Jordahl took IC through a densely vegetated section of thornscrub comprising one of these tracts, the El Morillo Banco Wildlife Refuge, just a stone’s throw away from the National Butterfly Center. “As we’ve seen at the neighboring La Parida Banco Wildlife refuge tract to the west of this tract, they’ve already begun bulldozing and excavating and literally turned the wildlife refuge there into mulch,” says Jordahl. And due to the waiving of federal environmental safeguards, there were no surveys carried out to determine what the impacts of those actions will be.

“Right now we’re actually standing in a national wildlife refuge tract of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge. This very area where we’re standing right now could potentially be bulldozed to make way for the border wall and the enforcement zone that will accompany the border wall at any point in the next couple of weeks.” Funding for the wall in this area has already been approved by Congress, and a contract has already been awarded to a contractor.

We walk past pink-flagged surveyor stakes driven into the ground on the levee indicating exactly where the construction would take place. The 654-acre El Morillo Banco tract of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge is a relatively small island of habitat on its own, but as one of over 140 refuge tracts in the area it contributes to a patchwork of habitat that is much more valuable. Since 1979 the refuge has been working with partners including the Fish and Wildlife Service to acquire land to string together in a connected habitat along the Rio Grande from Falcon Dam in Roma, Texas, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico for wildlife to use in order to connect breeding populations and move throughout the Rio Grande Corridor.

Additionally, the exemptions in the recent bill supported by Rep. Cuellar that excluded the National Butterfly Center and four other areas from border wall construction do nothing for the wildlife refuge tracts elsewhere in the Rio Grande Valley. “This loses sight of the grander purpose of these wildlife refuge tracts for use as a conservation corridor,” says Jordahl. “If we see walls rammed through all of the other wildlife refuge tracts, through families, farms and people’s private properties, even with these tiny open areas allotted in the construction exemptions, we’re really losing the environmental integrity of the entire region.”

“With border wall construction, we’re literally slamming an impermeable obstacle through the heart of that conservation corridor,” says Jordahl. “If the border wall was built here, the entire point of all of these conservation efforts and tens of millions of dollars poured into revegetating these areas, along with what people in the Valley have been fighting to protect for decades, is completely lost.”

As these lands are destroyed, so are the homes of the dwindling remnants of endangered and threatened species. Land-dwelling animals trapped north of the wall will be forced to compete for scarce resources and unable to connect with other populations of their species trapped on the southern side of the border. In the Rio Grande Valley, the nearly extinct Texan ocelot is particularly at risk.

The environment of the Rio Grande Valley is perfect for animals like the ocelot who are native to the region, but less than one percent of this species’ native habitat remains in South Texas. With only 50 ocelots left in the United States, mostly confined to the Rio Grande Valley, this species’ best chance of survival includes connecting with an ocelot population south of the border in Northern Mexico through the use of these wildlife refuge tracts and corridors. The goal has been to reconnect these two populations in order to have a healthy genetic diversity within the population, says Jordahl, but the border wall would destroy these chances at recovering the ocelot as planned for in the recovery plan for the species, making it likely that the remnant population in the U.S. would go extinct.

In addition to the destruction created by the wall itself, the wall’s proposed protection mechanisms of flood-lighting in the enforcement zones are expected to throw off nocturnal species in the region such as the ocelot, which relies on sunset and sunrise cues and hunts at night. “We heard border patrol telling Marianna Treviño that their plan was to light up this area like a ‘war zone’,” says Jordahl. The flood lighting planned for the top of the border wall will impact wildlife that has never evolved to deal with non-natural hunting, impacting the animals’ abilities to hunt, to sleep, to mate, and other factors that haven’t been fully studied yet, Jordahl adds.

BORDER PATROL RESPONSE

“Considering there are numerous public interests involved, it’s profoundly unjust that they have shut the community out of this process from the very beginning,” says Jordahl. Normally, given the scale of a project like this, a series of public scoping meetings would be held for the public to learn about the project and provide feedback. In this case, not a single public scoping meeting has been held, says Jordahl, despite the fact that the massive project will fundamentally change the local landscape.

“Instead of actually meeting with Border Patrol folks, we’ve had to hold protests outside their headquarters,” says Jordahl. “We’ve demanded for months that Border Patrol hold a public hearing on this issue so people impacted by the project can go and make their voices heard. The only thing they’ve done is hold an online webinar where they cherry-picked questions that were easy for them to answer it — and it was only in English.”

Spanish is the predominant language in the Rio Grande Valley, and as one of the poorest counties in Texas, Hidalgo County specifically is home to many who will be affected by border wall construction but don’t have a computer or internet access.

“Really, Border Patrol has made no effort to reach out to a lot of the people on the ground here, and by holding online webinars like that, they’ve cut the poorest folks — who are probably going to be the most impacted by this project — out of the process.”

BUILDING COALITIONS

A broad coalition has united a diverse set of people set on defending these lands, and the National Butterfly Center has found itself at the heart of an outpouring of anti-wall activity. “We have become a home for artists and other activists who are interested in sharing their perspective on the way that the border wall, the waiver of laws, and the militarization of our community affects people in this region and impacts communities,” said Marianna. “We’re fortunate that they have come together to express their outrage and to stand with us against this encroachment and against this atrocity.”

This included uniting with military veterans, the peoples indigenous to this land – the Esto’k Gna of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Nation, artists including the world-renowned Ron English, and a broad coalition of local activists and activist networks nationwide.

Veterans hailing from the Sierra Club’s Military Outdoors program camped in tents on National Butterfly Center grounds for a week this spring in protest of the wall. “The border wall and militarization of border towns is a direct affront to the democratic principles, values, and protection of human rights that the U.S. military is entrusted to uphold,” said Rob Vessels, senior campaign representative for Sierra Club Military Outdoors and an Army veteran. “By manufacturing a crisis on the border and illegally declaring this fake national emergency, the Trump administration has chosen to abuse the Constitution, tear through special places like the National Butterfly Center and cause irreversible damage on our own soil — all for a useless and destructive border wall. As veterans of the United States, we plan to join in solidarity with border communities to oppose the wall and humanitarian atrocities happening on their lands. We continue to side with the people, public lands and values we committed to serve.”

During this same week, the peoples indigenous to this region — the Esto’k Gna of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Nation — invited the veterans to join them in gathering willow branches for construction of the sweat lodge as the Esto’k Gna rebuilt one of their ancestral villages at the National Butterfly Center.

The Butterfly Center has united with the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, providing its members with a spot at the center to rebuild their ancestral villages in the way of and in direct opposition to the border wall at sections all along the Rio Grande. One of these villages was set up at the National Butterfly Center for approximately a month and a half.

Allies of the Carrizo/Comecrudo and military veterans help clear an area for sweat lodge construction at the National Butterfly Center.

“Part of our purpose here is to bring healing and rebalancing to our Indigenous lands,” said Juan Mancias, chairman of the Carrizo/ Comecrudo Nation of Texas. “We hope that through the veterans’ participation with us in gathering willow branches for sacred ceremony and in sending out our voices in fellowship with Creation in one of the last remnants of the natural habitat of the Rio Grande Valley, that they will receive the healing and wholeness of our Mother Earth, which we wish to preserve for all living beings.”

Dr. Christopher Basaldu, an anthropologist and member of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Nation, agreed. “Indigenous peoples’ original lifeways are often based in living relationships with respect and being a good relative. That’s not just being a good relative to your human relatives, but to all your relatives in life within your homelands,” says Basaldu.“Invasion, genocide, forced conversion and colonization breaks those relationships and forces the people to adapt to a less respectful life.”

Through the destruction of the environment, Basaldu explains, “we have forgotten the most important relative, our Mother Earth.” Through these villages, Basaldu sees healing in “living in a way that restores the respectful relationships between the people, and between indigenous people and their homelands, their sacred history, and their ancient ceremonies and to their languages and healing all of the interconnected relationships that human beings have been disrespecting — including the plants, animals, the sea, the rivers, the mountains, the land, the sky, the rain, all of it. In order to heal ourselves, we have to again live all of our relationships with all of our relatives with respect, with love and care.”

GATES

For every mile of border wall built, the government is confiscating and clearing approximately 18 acres of land. Beyond that, the land remains in the ownership of the private property owner.

In order to solve this problem, gates will be installed in the wall to allow private landowners to still access their property. This means that they’re going to have to put gates in the border wall. The National Butterfly Center is not the only private property being seized and affected in this way; hundreds of private property owners are currently being affected. Approximately $49 million of FY 2017 border wall funding was allotted to go to the construction of 35 gates in the Rio Grande Valley to close holes in the existing 55 miles of wall, with the first of the gates being built in late 2018, according to documents obtained from CBP.

Residential subdivisions, churches, country clubs, golf courses, and businesses will all be blocked off behind the border wall, with residents who need to access their property.

A CBP official responded to a request for comment, “In some cases, local border patrol sectors have entered in agreements with landowners and stakeholders to allow certain gates to remain open for extended periods of time specifically during business hours to avoid issuing a code to each visitor.”

“At the National Butterfly Center, we will have a giant electronic gate with an electronic keypad. Border Patrol told us we will have the code to open and close our gate and we can share another code with every one of our members and visitors,” says Marianna. “That’s 35,000 people a year. In residential divisions everyone who owns or rents there will be provided a code; and so will service providers like the Fire Department, ambulance drivers, streetlight workers, sewer maintenance providers, and every meter reader and cable repairman.

“Effectively, this means that any person who might want to get past the border wall through one of those gates no longer has to bribe or blackmail a law enforcement officer or a property owner,” says Marianna. “They merely have to join the National Butterfly Center.”

PUSHBACK

The backlash against the Butterfly Center for defending these lands has been immense, including from Butterfly Center members. “We’ve had pushback from all corners. We’ve lost members and have had lots of hate mail,” she says. “Staff members, me personally, and the center itself have all received threats.” In response to these threats, butterfly center staff have had to install cameras throughout the property and have various safety trainings. “If we find a backpack at the picnic area, we no longer pick it up. We call law enforcement,” says Marianna.

Muñoz has met with many wall supporters from out of the area who “want to see the center before it closes, thinking the wall is going to go up no matter what — and they want it to,” he says. “But once they visit the center itself, walk the area and all the way to the river without a policeman next to them patrolling, they realize that it’s not dangerous. We have fishing on Sundays so some of them come and fish here and understand that this is not exactly what is being pictured on the news.

“We invite anybody who comes in here to take a walk back there and see how peaceful it is so you can get a better understanding,” he adds. “Fear is something that pushes so many people, but it takes physical walking back there for them to be able to understand what it is actually like. These people listen to the news when the news listens to the president or others saying that all these bad things are happening here – but they’re not here. They don’t see how it really is. We see it.”

MISPERCEPTIONS ON THE BORDER

“There are lots of folks who say that the border has to be secured, that this is a dangerous corridor of ‘bad people and criminals and illegals entering,’” says Marianna. “I report for work here six days a week. If that were true, if that were our reality, we couldn’t be open. No one would work here. No one would pay to come to activities and events here. And we sure as hell wouldn’t be able to have the annual sleepover under the stars where Girl Scouts, little girls, their moms, and troop leaders come spend the night here on the banks of the Rio Grande River without weapons and without police guard.

“So the reality of what’s happening on the border lands, the reality of what’s happening with regard to drug trafficking, human trafficking, all of these things that people should be alarmed about is that by the government’s own admission, the majority of it is happening at legal ports of entry and bridges at sea ports, at airports, nowhere near the southern border in terms of human migration,” she says. According to a 2017 report by the Center for Migration Studies, visa overstays have “significantly exceeded” illegal border crossings each year between 2010 and 2017, the latest year both of these metrics are available. In 2017, more than 700,000 people overstayed their visas in the U.S, according to a statement released by DHS in 2018.

“And this issue with [legal] asylum seekers, refugees, immigrants — Congress is derelict in its duty,” says Marianna. “But the public is too blinded by the smoke screen of, fear, greed, and racism to see through it.”

Follow Intercontinental Cry on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

Follow Garet Bleir Journalism on Facebook or @GaretBleir on Instagram and Twitter for videos, podcasts, and long-form article updates to come regarding these issues and published with Intercontinental Cry.

- Video Series: Juneteenth Voices Demand Change - June 19, 2020

- Border Wall Plows Through, Despite Pandemic - April 17, 2020

- ‘There is no safety. There is no family. There is no home.’ - November 6, 2019

border wall Center for Biological Diversity Laiken Jordahl Marianna Treviño-Wright National Butterfly Center