By Tracy L. Barnett

Texas Journey magazine

March/April 2014

Deep in San Antonio’s Westside, at the corner of El Paso and Chupaderas streets, the 10-foot-tall face of Jesus overlooks a scrappy landscape, a world of sadness reflected in his weary brown eyes. For more

than a decade, the locals have come to this corner to pray.

There’s a story about this corner that artist Cruz Ortiz likes to tell, a story that’s been retold so often it’s become local lore. One time, Ortiz showed up at the mural and saw a woman resting against a nearby pole.

“Are you okay?” he asked.

“I come here every Sunday,” she replied. “Because they won’t let me in at the church.”

That corner had become her church, her resting place, her place of hope.

On other corners in this neighborhood, people find stories of triumph and defeat, of musical legacy, of loved ones lost, and of celebrated heroes.

At last count, more than 100 murals grace the buildings of San Antonio’s Westside. They represent the evolution of our country’s Chicano Art Movement, which began in the 1960s. In San Antonio, it was a time when even the most outstanding Chicano artists couldn’t find a venue to accept their work, recalls Ellen Riojas Clark, who taught a class on local art history at the University of Texas at San Antonio and has been honored with a place on one of the city’s most famous murals, located inside Mi Tierra restaurant, in Market Square.

What the murals helped to do, Clark says, was to create a space for a new art form, and add to the canon of American art in a way that expressed the experiences and history of a people. “You can give credit to San Antonio for bringing the cultural life of Mexican Americans to the palette in a way that had not been done before,” she says.

The nascent movement gained steam in the ’70s and ’80s in the Westside housing projects through a now-defunct community arts group that sought to give the young people a sense of their rich heritage. In the ’90s, a new generation picked up the torch—and their paints—to fuel the San Anto Cultural Arts organization, which has led some 40 local mural projects in the past two decades.

A blackboard at San Anto’s office chalks out the challenges of this forgotten neighborhood: 96.2 percent: Hispanic. 53 percent: No high school diploma. The statistics manifest on many levels: high rates of unemployment, teen pregnancy, and incarceration, for example, leave a trail of diminished hopes. Murals help channel that disillusionment—and rage, in some cases—for both the artists and the community, which is involved in every step of the process, from planning the themes in a series of neighborhood meetings to helping paint the murals.

A panel from “Brighter Days,” by Adriana García

“People ask me if it’s safe to come over here and I’m not going to sugarcoat it,” says John Medina, San Anto’s public art program manager. “Westside is a real place with real challenges.”

Increasingly, however, visitors want to go beyond the finely manicured River Walk to see another face of the city.

“People are making the effort to seek out the authentic San Antonio,” Medina says. “That’s what these murals represent. The artists grew up in these neighborhoods and still live here and work here.”

Those who make the effort are rewarded with one of the richest experiences San Antonio has to offer. The best way to understand the murals is to tour the area with one of the artists, which can be arranged through San Anto. Ruth Buentello, who served as the organization’s mural director for three years, shares some unforgettable stories with those who accompany her.

On the corner of Trinity and San Patricio streets, for example, the Virgin of Guadalupe joins a funeral procession while Christ steps down from the cross to set free a white dove in Peace and Remembrance, painted in 1999 to honor neighbors felled by violence; every year, on Día de los Muertos, people gather at the mural to add one name from that year’s tragic toll.

On the corner of West Commerce and Navidad streets sits La India, an old-fashioned herbolaria, its front wall a mosaic-embellished glimpse into the herbal pharmacy of the ancestors in a style reminiscent of the ancient Mayan codices. As the story goes, the artist, Mary Agnes Rodríguez, approached the owners in 2004 with her concept, and they balked, fearful they’d become targets of mal ojo, the evil eye. Rodriguez persisted, and eventually the owners relented. The business has flourished ever since.

Terror spills from a wall on Buena Vista near Colorado Street: a lunging pit bull, a grasping fist, a gas mask, flashing police lights—and in the midst of it all, a worried mother. It’s called Piedad, and it’s part of Buentello’s own evolution: At 17, two years into her apprenticeship at San Anto, she was invited to lead this mural project.

Buentello, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, found her calling as a professional artist under the mentorship of San Antonio’s muralists. It’s this cultivation of talent in a forgotten population that may be the murals’ most important legacy, according to Alex Rubio, one of Buentello’s mentors.

As a teen in the 1980s, Rubio joined the team creating a mural for the Westside housing projects, his childhood home. Nowadays Rubio, currently the MOSAIC Program artist in residence at the Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum in San Antonio, is nationally known for a signature style, but his greatest pride comes from his work as a mentor to a new generation that now has better support and a sense of its own history.

“I think the most important thing that visitors will see, if they take the time to come see the murals,” Rubio says, “is a multigenerational movement of artists, carrying on that cycle of inspiration and mentorship.” ✪

Freelance writer Tracy L. Barnett is the former travel editor of the San Antonio Express-News and the Houston Chronicle. Follow her adventures at tracybarnettonline.com.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

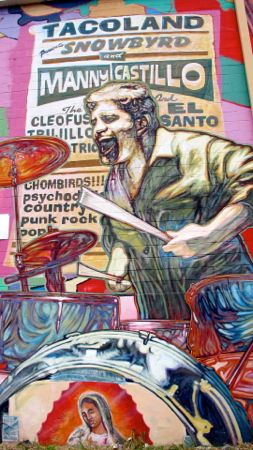

Adriana Garcia Alex Rubio Chicano Art Movement Cruz Ortiz Ellen Riojas Clark featured Manny Castillo Mary Agnes Rodriguez Ruth Buentello San Anto Cultural Arts San Antonio murals Westside San Antonio

I received this magazine in the mail this week and I was sad to see there was no mention of San Anto founder Manuel Diosdado Castillo. Jr. or past mural coordinator and artist Gerardo Quetzatl Garcia considering half of the murals pictured were done during the time they worked together. I’m glad other San Anto artists and their work are featured but I feel the need to acknowledge these two men who without them these murals would not exist.

Thank you for writing, Abril. I’m sad, too, that Manny doesn’t appear in this story. He was actually in the first version and I didn’t notice that part had been cut until you drew it to my attention. His legacy lives on in a thousand ways, as I wrote in the original story, and I was just one of thousands who was blessed to know him.