SAN LUCAS TOLIMAN – I arrived at the home of Rony Lec of the Mesoamerican Permaculture Institute (IMAP) at 9 a.m. and found him meeting with a group of young men from Ajpu, a local youth group. The post-storm response of the government was slow and disorganized, I had heard from various people around town, and the group echoed these concerns.

Emergency food and supplies had arrived from the federal government and had been carried off by whomever happened to be around instead of being distributed in an organized and equitable way; no one had any idea how many people were homeless, and who they were; people who were not in the shelters were not being taken into account; the list of immediate problems went on.

Rony was organizing a group to help with the immediate disaster response, gathering data that would allow IMAP to respond with a long-term plan to help with recovery and prevention. I had offered my services as a documentarian for a few days, to try and get the story out about what’s going on here.

After a quick meeting, we decided to divide into two groups: Rony and Felix would attend the meeting being called by local NGOs, and Emilio and Eliazar would accompany me to the affected areas and to the shelters to do interviews.

We headed downhill to the edge of town, where a series of landslides had occurred. It didn’t take long. Within five minutes we encountered a woman picking through the remains of her brother’s house.

Ismael Santiso Yoxon had lived with his family in this house for 16 years; it was built on land he had inherited from his grandfather. He had survived many storms, including Hurricane Stan, with no problems.

A huge chunk of hillside had fallen off and slid down, smashing into his home, flattening the back wall and filling it with dirt. The chicken house with its 50 chickens was buried, along with his other animals.

“He doesn’t have any idea what he’s going to do,” said his sister, Elvira. He and his wife and daughter are currently staying with his mother-in-law, but there’s not room to continue living there.

The case is a typical one; the land above his house, like much of the land on the hillside, was divided up and rented out with the blessing of the municipal government, despite the instability of the soil. The neighbors began cutting trees and put in a milpa on the slope just above Yuxon’s house, and this cornfield was what had collapsed.

We wished Elvira well and made our way up the hill, where we encountered an abandoned house with the front torn off. Inside, the bed was covered with dirt, and a cluster of green bananas had landed on top. The walls were askew, and dirt and rocks practically filled the structure.

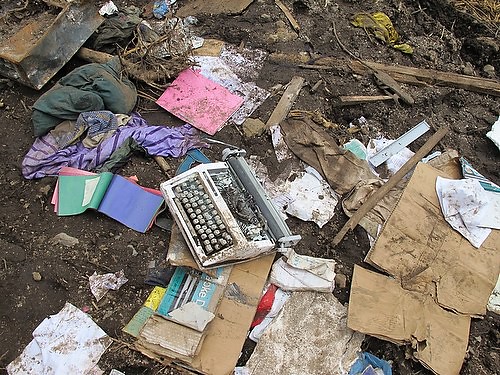

Children’s schoolbooks and backpacks and clothing were scattered about in the mud, with what was left of a manual typewriter tossed in the middle of the pile.

No one was near, so we made our way back down the hill, past two other abandoned houses, where we encountered Ana Cu and Romelia Guarcha Sep, two women in traditional dress who said they knew the affected families and would take us to them. We accompanied them to the stricken neighborhood called Nuevo Amanecer, or New Dawn.

Regina Castro was standing on what was left of her back porch, looking out at the expanse of mud and the fallen trees that covered what was once her brother-in-law’s house.

“We were here on Saturday in the rain and we started hearing the sounds and we got scared, so we grabbed the children and ran,” she said. “We didn’t have time to get anything together – we just ran. Fifteen minutes later, the hillside fell down.”

Ana and Romelia’s homes had not been damaged, but they didn’t feel safe living there anymore, seeing what had happened to their neighbors.

Marcelino, Leandro and Luis Acibinac were the three brothers who lost their homes nearby. We found Liandro just up the hill, looking over the mud that buried his home. The only sign was a small pile of clothing on top. How they had gotten there, I didn’t know – perhaps they had been drying on the line.

“Here was the kitchen… here was my bed,” he said, pointing out where his house once was. “We didn’t have time to recover anything; we only have the clothes on our backs. Only God knows where we will go now.”

Esdras Mardoqueo Baran was picking over the remains of his sister’s house, nearby. His house had not been hit, but he didn’t feel it was safe to continue living there.

“We’re all at risk,” he said. “The river finds its path, and the rainy season has just begun. What will we do? Only God can say.”

Up the hill, Salamon Alvarez de Leon was checking out the remains of his friend’s home. The land above their homes had been converted to a coffee plantation, which doesn’t have the same ability to hold the soil as a native forest.

His friend, Rafael Ajcot, had had six children, ranging from 6 to 16. “This is part of the problem – all of the people,” said Alvarez. “The deforestation, the population growth – in 1970, we had 5,000 people living in San Lucas. Now we have 40,000. Where are they all supposed to go?”

Created with Admarket’s