SAN SALVADOR – I have great hopes for this little country on the Pacific Coast, this country of volcanic landscapes and volatile history – a country whose name means The Savior. I am curious to learn what the crucible of revolution may have wrought on the human spirit here. Much has been written of the Maras, the gangs with roots in the paramilitary death squads and in the barrios of Los Angeles and Houston and New York, and their ruthless exploits throughout the country – for the record, I haven’t seen any yet.

Far less has been written of the revolutionaries who turned their passion for justice into grassroots movements for change.

El Salvador left a deep imprint on my young consciousness in the 1980s. The assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero, the rape and murder of four American Catholic churchwomen, and the bloody massacre of four Jesuit priests at the University of Central America shocked me into learning more about my government’s key role in these horrors and many more.

So part of my journey through a now peaceful El Salvador will be the volcanoes, the beaches, the cloud forests and the charming colonial towns. But part of it will be to trace the route of U.S. financed terror through this heartbreakingly beautiful landscape, and to find the places where the phoenix has risen from the ashes to create beauty of a human sort.

This part of my journey began at the National Cathedral, where hundreds of thousands gathered 30 years ago to lay to rest a martyr: Archbishop Oscar Romero, advocate of the poor, who was shot down as he raised the chalice in a Mass. The funeral ended in a massacre as riflemen fired on the crowd from the rooftops; an estimated 44 died in the chaos. In March, the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination, the newly elected president – Mauricio Funes, a leader of the former guerilla group FMLN – addressed hundreds of thousands of cheering Salvadorans, acknowledging for the first time the former government’s role in the horrors and saying, “Never again.”

Today’s National Cathedral, with its soaring churriguresque dome and its brightly tiled façade depicting campesino life, is an oasis of calm amid the hubbub of the historic center; crowds mill about in the neighboring plaza and the nearby open-air market that seems to stretch for miles. The distant history of war is as remote and yet as present as Monseñor Romero’s austere tomb below our feet.

The second stop on this journey is a half-hour’s bus ride from the center of San Salvador on the leafy, peaceful campus of the University of Central America. Students and teachers walk the lushly landscaped paths and visit under the palms, and a few make their way to the Oscar Romero Center to pay their respects to the Jesuit priests who were wakened from their sleep here 21 years ago to face the guns of assassins, along with their housekeeper and her daughter.

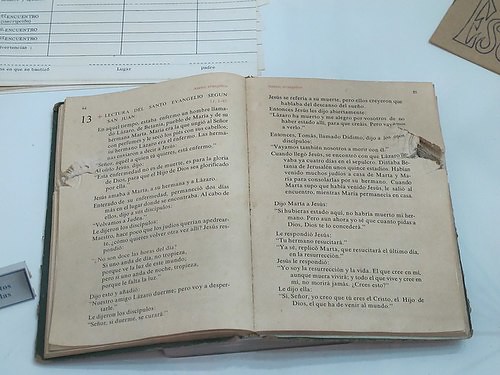

A group of visitors left in silence as I entered the small museum. The images will stay with me always: A Bible with the tracks of a bullet ripping through its pages; the blood-soaked, bullet-ridden clothing of the six priests; personal items from their lives there at the University. Photographs of the four U.S. churchwomen raped and murdered on Dec. 2, 1980 by members of the Salvadoran National Guard, together with their books and clothing – some stained with the women’s blood.

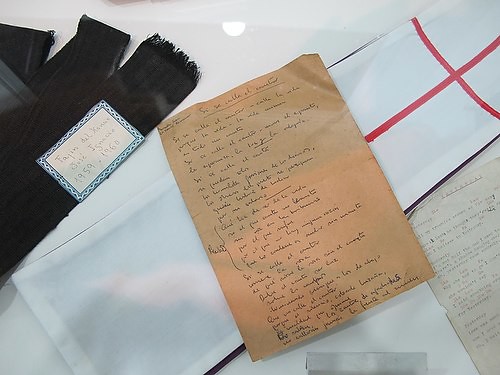

A photograph of Jesuit priest Ignacio Martín Baró stays with me, as well, playing his guitar and smiling. Among his items are the handwritten words and chords of “Si se calla el cantor,” “If the singer is silenced” – made famous by the legendary Argentine singer Mercedes Sosa.

“If the singer is silenced, life is silenced/Because life, life itself is a song/If the singer is silenced, Hope, light and joy die from fear.”

I stepped out into the light, into the garden planted in their honor, not far from where the priests fell and bled – a quiet place where a hundred roses bloomed and swayed in the breeze. Outside, students laughed and talked and planned for the future.

A light tune filters in on the breeze. A young man sits in the shade and plays his guitar.

Here in El Salvador, I am touched to know, the singer has not been silenced.

Created with Admarket’s flickrSLiDR.

- ‘Planting Is a Right’: Guadalajara’s Urban Ag Rebels Rally Against Proposed Regulations — Again - January 21, 2026

- The women who kept a Mexican pueblo above water — and stopped a megadam - January 15, 2026

- Reading the Earth: How Mexican scientists are using nature to find the disappeared - January 7, 2026

El Salvador Ignacio Martín Baró Jesuit priests liberation theology Oscar Romero San Salvador UCA

I love looking at your photos! Hope all’s well.

Back in the U.S. a week, I finally got a chance to peek at your website. Lovely piece … glad to read something from a U.S. journalist about El Salvador other than the burning bus this summer…